THE STORY OF 300

JANUARY 3, 1968 — MAY 19, 2019

1. STREET SURVIVAL

2. SLUMS OF BERKELEY

3. AGAINST THE CLOCK

4. THE EVICTION INDUSTRY

5. BLOWING THE WHISTLE

6. THE POLITICAL MACHINE

7. THE LAST DAYS OF 300

AFTERWORD

Editor’s note: Street Spirit is proud to publish this long-form story of the life of 300, a life-long Berkeley resident and community leader who tragically passed away in 2019 after being evicted from his home. Read the full letter from the editor here.

Street Spirit needs your help. Make a donation of $20 or more and receive a bound and illustrated copy of “The Eviction Machine” as our way of saying thanks!

Estimated time to read: 80 minutes. Grab a coffee.

1. STREET SURVIVAL

I met 300 sleeping on a bench outside Au Coquelet Café on University Avenue one late night in the summer of 2013. He had a burly mustache and he wore a dark poncho with a black skully on his bald head. A square black cross hung from a black shawl around his neck. He held a heavy book about the American origins of Nazi eugenics, and we talked for a while about the history of fascism.

300 was born in Berkeley in 1968, he went to Berkeley High, and he lived in Berkeley most of his life. He lost his housing during the 2007 recession, and he sheltered at familiar spots around Berkeley for years. He used an Obama phone to get wi-fi at the café, and he slept sitting upright on the benches outside. A few years ago, those same benches were flipped backward and filled with flower pots so unhoused people couldn’t shelter there.

I studied in the café every night until 2 A.M. After closing, I’d sit outside and talk with 300. He had a photographic memory and he told stories like the film was projected in the back of his dome. He taught me about the history of Berkeley and growing up in the time of the Black Panthers. He saw abandoned storefronts and high-rise towers and reminisced about the shops and venues that used to stand there. He worried about who was rummaging through his shopping cart when he was asleep. His voice got low when a police officer walked up and addressed him by his government name.

As silhouettes drifted past in the dark, he pointed out predators and prey, who was abusing, who was being abused in the shadows of foyers and alleyways at night. That summer, I got an education in street politics. When summer ended, I moved away for school and I lost touch with 300.

In the fall of 2014, after I moved back home, a jury acquitted a police officer who had killed a young man named Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. I saw a crowd marching up University Avenue and I joined them, followed by police shooting tear gas grenades and rubber bullets at our backs. 300 was sitting on the bench outside the café again, watching the scene and the cloud of smoke. I stopped to say hello, and he gave me the number to his prepaid flip phone.

I caught up with 300 a few days later at the “cop shop,” the Berkeley Police Department building on Martin Luther King. He was doing masonry work for a sheet metal company on Gilman Street and recycling aluminum cans to make ends meet. Every other week, he went next door to City Hall to attend the City Council meetings. His portable radio played KPFA while he sat on the steps of the cop shop every night.

The cop shop was 300’s last resort. He had camped with tree-sitters at the Memorial Stadium oak grove, until the university destroyed their tents and cut down the trees. He had slept below the arches of his church on Bancroft Way until the clergy chased him off, dripped in jewelry and driving foreign cars. He had lived in a tool shed behind a house where he worked as a gardener, but the owner snapped the knob off the door, angry that 300 brought other unhoused people to visit. 300 had no family ties: he was estranged from his twin sister, his only living relative.

300 wasn’t eligible for a subsidized apartment unless he signed a form declaring a “mental illness” or “disability”—he refused, because he understood that those labels could be used to incarcerate him. He was trapped in a circle: “I could not find work because I did not have a place to live, and I could not get a place to live because I could not find work.” The police station was the last, safe place he could find to sleep. He maintained the grounds around the Public Safety Building, planting flowers, trimming hedges, and sweeping debris. In exchange, BPD quietly allowed him to set up camp on the front steps.

The police station is quiet at night, and 300 spoke freely when I met him there. He told stories about his childhood growing up in a violent neighborhood in Southwest Berkeley segregated by Jim Crow. The parking lot by his home was a popular place for dealing dope and turning tricks, and Berkeley police left the block to its business. His mother lost her house to a mortgage fraud scam in 1991, and she started renting a unit in a duplex near San Pablo Park. She was found dead in her apartment, alone, in October 1996, at age fifty-three. 300 believed she was murdered, but BPD ruled her death an “accident” and didn’t investigate further. He put police racism in simple terms: “They classify all African-American people as either criminals or servants.” He meant that BPD didn’t consider her life worth protecting.

300 was a “street therapist” and he crossed paths with people from all walks of life. He was always outside: if I named anybody in the city, he’d probably met them, from the gas station clerk to Lil B the Based God. He knew my landlord, my next-door neighbor, and the man who slept on the bench by my house. The nephew of a notorious Black Panther gun-runner visited him often. A Google engineer paid rent on a storage unit for 300 to keep his belongings safe. Graduate students were glad to have someone listen to them talk about their research. Once 300 started a conversation, he could swap stories for hours.

I heard a lot of crazy “shite” from 300. He never used curse words, and he always found a polite way to describe bizarre and unbelievable episodes. He told tales of zombies shambling from Barrington Hall, and dance parties with the crown prince of Norway. A BPD patrol officer thought 300 was hallucinating a pink furry animal running sprints on Shattuck Avenue, then doubled back to apologize after he met the man in the fur suit later that night. I learned about Berkeley pimps, politicians trading sexual favors, and police who smoked meth from the evidence locker. “I was a dancer for many years,” he often said with a wry smile. “I understand body language very well.”

Sleeping outside took a toll on 300. His body was breaking down in the cold. He carried the heavy anxiety of street survival. A few years before I met him, he got jumped and bludgeoned in the head near the downtown public library, where he was sheltering at the time. He had daily headaches but he hated going to the hospital, so my father, a neurologist, came to break bread and give a street check-up. My mother was a history professor at the university, and she packed hot Indian food for 300 cooked by my uncle. 300 always reminded me how lucky I was to have a big family and a strong system of support. “This is my living room,” he said, pointing around Civic Center Park. “I have no privacy. It’s cold and people come and go as they please.” He told me: “You’re lucky your worst enemies are within you. You don’t know what it’s like to be surrounded by people who wish you were dead.”

On the street, you can get violated by anybody at any time. As a survival tactic, 300 became friendly with many Berkeley police. He learned police lingo and he addressed them by rank. He was tapped into department politics at all levels of the BPD, from the police chief to the custodial crew. When one detective realized that 300’s outlandish street tales were true, he gave 300 a small field recorder for his protection. 300 kept the mic on his body, in case the detective tried to copy the memory card from his shopping cart while he slept. 300 said the police were always taking notes. He called them “secretaries with guns.” Some police on the graveyard shift confided in 300 because they had no one else to talk to in the dead of night. He told me about a patrol officer who jovially showed him a video of a savage beating filmed on duty. 300 thought the officer was traumatized and struggling to process what he’d witnessed. The officer stopped smiling when 300 said: “You’re not going to beat me like that, are you?”

Some people on the street viewed 300 with suspicion—he never touched drugs, and talking with the police gave him a reputation as a snitch. Sitting on the steps of the police station every night made him look even more like a rat. In the summer of 2016, 300 used to text me late at night and invite me to the cop shop steps. When I got there, I found him anxious about enemies prowling in the dark. At first I thought he was being overly paranoid, but soon I found out why he was afraid to be alone.

One early morning in August 2016, a White supremacist called “Creature” showed up at the cop shop steps before dawn. Creature and his crew liked to bully and harass 300. Creature was an antisemite, and he believed 300 was Jewish. Now, high on methamphetamine, Creature threatened to kill 300. He put his hands around 300’s neck and tried to gouge 300’s eyes with his thumbs.

The attack was outside the police station and the CCTV saw everything. Creature was arrested a few hours later. I visited 300 that afternoon, and he pointed to tiny drops of blood that stained the steps where he always sat. He refused to leave the cop shop. He had to get off the streets immediately.

A man named Kareem sometimes visited 300 at the cop shop in those days. Kareem studied industrial engineering in his country in North Africa. He came to America on a student visa, but he was now seeking asylum status: his city was under siege in a civil war involving the US military. He lived in a run-down building owned by an infamous slumlord, across from the 7-Eleven on University and Sacramento. Kareem had invited 300 to sleep in his room, but 300 declined. He knew the landlord’s bad reputation and he didn’t want to share a crowded space with strangers. Now, after the attack, he was willing to get indoors by any means necessary. In November 2016, 300 moved into Kareem’s place.

2. SLUMS OF BERKELEY

Kareem’s landlord was “Sagwa,” a shipping merchant in Oakland Chinatown who owns real estate across the East Bay. In the 1980s, while in his twenties, he emigrated to California from Macau with his parents and elder brothers, and they purchased a fourplex apartment building on University Avenue. Sagwa’s family evicted all the tenants and lived in the apartments for a few years until, one by one, each of the brothers found their own house and moved out. In 1992, Sagwa and his wife bought a second fourplex, the twin of the first, mirrored across a concrete driveway on the same plot of land. Sagwa’s brothers were landlords on the east side of the driveway, and Sagwa was landlord of the west.

Sagwa was a slumlord. His building was in bad shape: taggers sprayed their names across the front of the building, and a makeshift wooden staircase hung limp from the side. Rat traps filled the back alley, and trash piled up outside like a small garbage dump. Inside, broken tiles paved the floors and wires poked through grime stains on the walls. The tiles were installed to replace bedbug-infested carpets, after an infestation was ignored for so long that tenants began sleeping in four-hour shifts to fight off hundreds of bugs. Sagwa often entered the units unannounced to do “inspections.” A student from Peru said Sagwa once woke her sleeping roommate by tickling their feet. A young woman from Thailand fell behind on rent, and she claimed Sagwa took her to a wooden shed behind the building and asked for sex instead of cash.

Many of Sagwa’s tenants were undocumented migrants who couldn’t afford to live anywhere else. When tenants complained, Sagwa threatened them with eviction or ICE. The tenants knew Sagwa as “Jack” or “Mr. Jack.” When he wasn’t around, Kareem and 300 called him “Sagwa” 「傻瓜」 a colorful Chinese word for “idiot” borrowed from a PBS children’s cartoon. Kareem said “Sagwa is the devil.”

Over the years, Sagwa was involved in many business ventures connected to his freight company: a seafood restaurant near Jack London Square, a pottery dealer on San Pablo Avenue, and a meat wholesaler near the Oakland Coliseum. In 2013, the IRS raided Sagwa’s properties on criminal fraud charges, and the feds seized piles of cash from his mansion in the suburbs and a warehouse in East Oakland. Sagwa’s attorneys in Chinatown made a deal with the IRS and the case was eventually dropped. But Sagwa was stingy, and he paid one of the lawyers twenty-thousand dollars less than what they agreed. The lawyer sued Sagwa to recover his fees, and he aired the IRS investigation files out in the public court records. The files shed some light on the life of a slumlord: on one invoice, the lawyer billed Sagwa for a phone call to the FBI to ask them to return his kids’ homework, time spent searching for Sagwa’s accountant who disappeared to Hong Kong, and helping Sagwa deal with “black lady tenant issues.”

The East Bay slums were formed by Jim Crow geography. Hill districts like Rockridge were “Whites-only” neighborhoods, and suburbs like Lafayette were “sundown towns” where non-Whites were banned after dark. From the early 1900s, Berkeley used “zoning rules” and “land use” codes to enforce racial segregation. Laundries were outlawed neighborhoods to evict “Orientals,” and dance halls were banned to prevent “invasion of Negroes.” The Elmwood district was a “single-family” residential zone (one house per lot) designed to separate wealthy, Whites-only Claremont from crowded apartments filled with poor migrants. Non-Whites were not allowed across the “color line”—north of Dwight Way and east of Grove Street (now called “Martin Luther King”).

Sagwa’s building stood at the corner of University and Sacramento, along the border of a “redlined” district south of University, where “undesirable” groups were settled. Sagwa operated an illegal rooming house at the western fourplex. The building was zoned for “single-family” apartments: one lease per unit, four units in the building. Instead, the landlord ran the building like a hostel, packing tenants into cramped rooms stacked with metal bunk beds. Each tenant had their own lease for $450 per month, one tenant “per bed.” Sagwa collected payment in cash, and tenants usually made handshake agreements with no written contract.

The fourplex was a trap house. An Afghan man lived upstairs with his wife, daughter, and mother-in-law, and he said in a court testimony that the building was “more like a drug den than a place where you could call home.” Two men in the adjacent unit on the second floor were partying with methamphetamine and they had frequent guests. They bullied Kareem and anybody who crossed their paths in the hallway. One of them, a pale, thin man called “Skinny,” was often found slumped and strung out at the foot of the staircase.

Sagwa brought new roommates often and without warning: after seeing many tenants come and go, Kareem was now living with two women who preferred cocaine, and a quiet student from China who washed her clothes in the sink every night. The student’s bunkmate used to party all night, puke in the sink, and piss on the bed. 300 called the police when she tried to break into Kareem’s room. One night, during some argument, she swung on Kareem with a cooking spoon—Kareem called the police again, and she left for good. The other women moved out soon after. By the end of November, it was just Kareem and 300.

300 invited me over while they were cleaning up the old tenants’ stuff. The living room was still cluttered with piles of junk left behind by the woman who slept there. He was embarrassed of the mess, so he let me in through the back door and ushered me into Kareem’s room in the corner. The walls were covered in paintings and vintage travel posters from Africa. A map of the world hung next to a blue print of a white dog, and a blue mandala was draped across the window as a curtain. Kareem’s hospitality made the room feel much bigger than it was. He brought dinners for each of us from the 7-Eleven on the corner: a microwave burger, a banana, and a chocolate brownie. He plugged his busted laptop into a pair of speakers and we played beats off SoundCloud. At night, Kareem slept on the floor; he insisted that 300 sleep on the bed. Kareem had painted a name on a glass lampshade on the ceiling: “El Doggy House.”

When 300 moved in, Kareem handed him a packet of papers he’d found taped to the front door. The words UNLAWFUL DETAINER were printed at the top: 300 immediately recognized them as eviction papers. Kareem was fed up with the broken-down apartment, and he had demanded the landlord make repairs. The weather was getting cold, and the gas heater didn’t work. The landlord refused. When Kareem pressed him, Sagwa stopped collecting rent and filed an eviction lawsuit.

The eviction paperwork was fraud: it listed a “written lease” that didn’t exist (they made a handshake agreement) and it claimed Kareem was ten months and $4,500 behind on rent. Sagwa was accustomed to using these tactics, because most of his tenants could not afford to go to court. Legal papers and a big $ sign taped to the front door was typically enough to pressure a tenant to move out.

The landlord tried to intimidate Kareem into leaving. He stole Kareem’s notebook and looked through his immigration documents. He sent racist text messages to Kareem, came to the apartment at random hours and threatened to call immigration to deport Kareem. He told Kareem: “America will never love you.” Sagwa was very friendly with the two men living upstairs, and he often showed up at their apartment at random hours of the night to chat with them. Soon after 300 moved in, the upstairs neighbors’ hatred of Kareem enflamed. They beat him up in the hallway, called him a “snitch,” pulled out a knife and threatened to torture him. 300 encouraged Kareem to report the incidents to the police, which only angered the neighbors more.

300 earned his keep at Kareem’s place by sweeping, cleaning, and maintaining the apartment. He removed the junk left behind by the previous tenants and turned everything over to BPD. He gave the walls a fresh coat of paint and covered up the graffiti on the front of the building. He advised Kareem to call the Fire Department and Housing Code Enforcement to do inspections. Sagwa quickly figured out that 300 was the one bringing the government’s attention to the building.

Sagwa told Kareem he wasn’t allowed to have a roommate, but Kareem didn’t listen. Sagwa had no authority; they had never signed a contract. So, the landlord came up with new tactics. On November 22, 2016, the agent from Housing Code Enforcement came to inspect Kareem’s apartment and found more than thirty safety code violations. The same day, Sagwa went to the courthouse to file a restraining order against 300.

The restraining order was filled with lies and stereotypes of unhoused people. Three days earlier, Sagwa had tried to force his way into the apartment without notice, and 300 barricaded the door with heavy furniture. Sagwa described 300 as the “homeless friend of an evicted tenant.” According to Sagwa, the police warned him 300 was “very unstable,” and he feared he’d be “assaulted” by 300. He asked the judge for immediate enforcement without a court hearing, because 300 “appears to have emotional issues.” The judge granted it. 300 was restrained under a temporary emergency order until a December hearing that would make it permanent. The next morning, 300 gathered his belongings into his shopping cart and returned to the streets.

After sheltering at bus stops for a few days, 300 lost contact with Kareem. Anxious about Sagwa’s threats, he went to the police station to get information. Coincidentally, at the same time 300 was outside the cop shop, Sagwa called the police to make a false report of 300 “trespassing” at the fourplex. A BPD sergeant standing by the Addison Street gate of the Public Safety Building saw 300 on the sidewalk. The sergeant recognized 300’s name in his computer and decided to force a confrontation. 300 described the cop in a court testimony: “He was smoking a cigarette like Dennis Hopper in some kind of David Lynch film… talking to me like I was some kind of dumb animal, trying to coax me into the gate.” The sergeant didn’t try to verify Sagwa’s call. Even though 300 was ten blocks away from Sagwa’s building, the police corralled him inside the gate, twisted his arms behind his back to handcuff him, and fractured his left wrist.

The police detention was recorded in a BPD incident report, written by a lieutenant who spoke to 300 earlier that day. The report contained testimonies from one officer and two sergeants who were on the scene. The statements amounted to a cover-up. They each claimed that 300 was “agitated” and therefore justified in being detained; they each reported that 300 “made no complaint of pain” while being handcuffed. 300 kept insisting over and over again that he was nowhere near Sagwa’s building, and finally the sergeant called Sagwa back. Sagwa admitted that he hadn’t actually seen 300 that day: he tried to get into Kareem’s apartment but the door was still barricaded, so he just assumed 300 was inside. The police removed the cuffs, and 300 walked to Alta Bates Hospital, alone.

300 disliked hospitals and avoided them at all costs. But the night before the hearing on his restraining order, he had a sudden, stabbing pain in his chest that felt like a heart attack, and he landed back in Alta Bates’ emergency room. He said: “Just thinking about the landlord would make the knife in my heart twist.” The emergency room doctor gave a diagnosis of angina, restriction of blood flow to the heart. She saw he was under a lot of stress, and told him to go home and get rest. Later, 300 reflected on the hospital visit in a court testimony: “She didn’t know that Sagwa had made it illegal for me to go home.” He went back into the streets and didn’t sleep. At the break of dawn, he left for his court hearing at the Hayward Hall of Justice.

On December 12, 2016, Kareem testified to the court that 300 was his roommate. Sagwa admitted he had lied about 300 trespassing, and the restraining order was dissolved. 300 was allowed to return to the apartment—but Sagwa inflicted lasting injuries. With one piece of paperwork and a phone call to the police, Sagwa sent 300 to the hospital twice. 300 did not have health insurance, and he was billed more than a thousand dollars for each visit. Sagwa paid no penalty at all for lying to the police.

Enjoying this story so far?

Street Spirit needs your help. Make a donation of $20 or more and receive a bound and illustrated copy of “The Eviction Machine” as our way of saying thanks!

3. AGAINST THE CLOCK

Just ten days after the restraining order was lifted, Kareem and Sagwa were back in court. The court had issued a “default judgment” against Kareem in the eviction case. Default judgment is part of the “unlawful detainer” process, an accelerated court procedure designed for landlords to remove tenants from their homes as fast as possible. Every piece of paperwork has a “clock.” After the landlord posts a “Three-Day Notice To Pay Rent,” they can file a “Summons and Complaint” for unlawful detainer. Tenants are given five days to respond to the complaint. If they don’t file paperwork in time, the landlord wins the case “by default.” The decision happens without a hearing. The court prints a “Writ of Possession” for the landlord and notifies the Sheriff to post a “Notice of Eviction.” The whole process can finish in a few weeks. Then, the Sheriff comes to enforce the eviction with a locksmith and a pistol.

Kareem didn’t understand the process and he missed the deadline. But 300 knew the court system well: he’d fought multiple evictions before. Before the Sheriff arrived, he helped Kareem call the court to request an emergency hearing to halt the eviction. They went to the library, photo-copied pages from law textbooks, and pasted clips onto legal pleading paper. They argued that Kareem missed the deadline out of “excusable neglect” because he was not a native English speaker, and he did not understand the eviction papers.

When Kareem and 300 showed up in court, the judge looked at their makeshift paperwork and was skeptical. Kareem cried out: “Your Honor, we stayed up day and night working on this!” The truth was they had spent the previous night watching Mr. Robot on a pirate streaming site. But the judge still listened to Kareem’s story, and she agreed: the landlord’s eviction papers looked suspicious. She ordered Kareem to pay a $450 fee, one month’s rent, to “stay” the eviction, and gave him ten more days to file a response. Sagwa left the courthouse in a rage. When 300 and Kareem returned home later, they found someone had broken in and tossed Kareem’s belongings into the alleyway.

300 went to the Berkeley Rent Board to get help with the lawsuit. He carried a big, red leather luggage case with him, because he didn’t feel safe leaving his things at Sagwa’s building. But when he arrived at the office, the Rent Board staff refused to process his paperwork: they told him he could not prove that he was a tenant because he had no written contract. They advised him to visit the local legal aid organizations, the Eviction Defense Center and the East Bay Community Law Center. But these aid groups wouldn’t offer him legal representation. Instead, they gave him photo-copied, fill-in-the-blank legal forms for filing an “Answer” to the lawsuit. An “Answer” fast tracks the case to a jury trial, where you have slim chances of winning without a lawyer. The legal aid workers were flooded with cases and they had to process as many lawsuits as they could.

On the first night of the New Year in 2017, I got a panicked phone call from 300 and I drove to his apartment. 300 and Kareem had gotten into an argument. Kareem was a prolific artist and he painted beautiful murals on the walls of the alleyway. Sagwa had used the murals to threaten 300: two days before the court papers were due, he called the police to report that a “homeless man” was vandalizing the property with “graffiti.” Fearing more police violence based on another false pretext, 300 quickly covered up Kareem’s murals with white paint. Kareem was at work that night at the 99 Cents Store on San Pablo. He was feeling depressed, and he had a bad flu. When he got home and saw his paintings washed away, he had enough. He was tired of battling Sagwa and he wanted to move out.

300 refused to return to the streets: staying indoors was a matter of life or death. We sat and talked for a long time, and as the sun rose the next morning, Kareem agreed to keep fighting the case. They had only twenty-four hours to file their paperwork. 300 told me to do a Google search for “Motion to Quash,” a way to argue a lawsuit wasn’t “served” to the defendant in person. We found a sample document on a legal website, and changed the details to match the case. A few days later, the motion was denied, but it bought precious time. We found a template for a “Demurrer,” a motion arguing the eviction papers were filled out incorrectly—another way to invalidate a lawsuit without answering it. The landlord didn’t attach a “Three-Day Notice To Pay Rent,” a requirement for filing an eviction. For good measure, Kareem collected receipts and bank statements proving he had paid. The hearing date was set for February.

Kareem never made it to the hearing. A few days after filing his paperwork, he disappeared. His room was turned upside down and his things were littered across the apartment. His documents were shredded and the apartment key was on the kitchen counter. 300 cleared out Kareem’s stuff, and slept alone on a red leather armchair in the living room. The next day, 300 went to the courthouse and filed another piece of paperwork, a “Claim of Right to Possession,” which declared that he was Kareem’s roommate and added his name as a defendant in the eviction lawsuit.

With Kareem gone, 300 gave Sagwa’s building a new name: “Ghost House.” In February, 300 was allowed to represent himself at Kareem’s hearing, and he prevailed: the judge agreed with the Demurrer. A few days later, Sagwa filed a second, amended lawsuit. He cooked up a “Three-Day Notice To Pay Rent” and attached a copy. The notice was obviously fake and it was missing another paperwork requirement: it didn’t even state how much rent 300 owed. 300 filed another Demurrer. In March, the judge ruled for 300 a second time. Instead of amending the lawsuit again, Sagwa dismissed the case.

4. THE EVICTION INDUSTRY

Eviction is a highly profitable industry. At least one and a half million people face court evictions in California each year, and many more people leave their homes before a lawsuit is filed. There is a big demand for legal services, and many lawyers promise landlords fast evictions by any means necessary. There are far fewer attorneys serving tenants, because tenants who missed rent (who are the majority of eviction cases) usually can’t afford to pay a lawyer.

I sat in the red leather armchair at Ghost House and did my schoolwork, while 300 spent hours on the phone, calling tenant attorneys for help. His case was clear-cut: in Berkeley, the “Tenant Protection” law provides a guarantee of “habitability,” which prohibits a landlord from evicting a tenant if their unit has safety code violations. 300’s unit had more than thirty. But one after another, the attorneys told 300 ‘no.’ There is no payout for keeping someone in their home. One lawyer told 300 to call back after he was evicted—he had good evidence for a “wrongful eviction” lawsuit against the landlord, where they could win hundreds of thousands of dollars in a settlement.

An elderly housing attorney explained why nobody would take the case. In the 1960s, when that attorney was still in law school, tuition at UC Berkeley’s Boalt Hall was only a few hundred dollars; today, law students graduate with six-figures of student loans. Young lawyers can’t pay their debts to Sallie Mae by serving poor clients. The old man wouldn’t take the case because he was busy planning a ski trip, but he gave the name of another lawyer to try. Every lawyer 300 called would offer the phone numbers of a few of their colleagues. He went down the branching list, inevitably hearing the same answer: they had no time to work for free. After yet another rejection, 300 turned to me in frustration and said: “I don’t need an attorney, I have you!” I agreed to help him out until he found a lawyer. And so, I became 300’s paralegal.

Sagwa couldn’t keep up with 300’s legal tactics on his own, so he hired an eviction lawyer. 300 called her the “Poison Server.” She helped the landlord cook up fraudulent documents to extort money from 300 and pressure him to leave. 300 needed to convince city officials to intervene in the eviction, so he informed Berkeley’s Planning Department that Sagwa was violating the city’s zoning rules. Sagwa’s units were registered as “single-family” units, but he was renting crowded rooms by the bed, like a hostel. The lawyer covered up the scheme—in April 2017, she filed a new eviction lawsuit, falsely claiming Kareem was sharing a single “group” lease with four other tenants. Kareem and 300’s true rent was $450 per month. On the fake lease, Sagwa claimed the rent was $2,250 per month, a combined sum for five tenants. The eviction papers demanded 300 pay more than $10,000 in back rent and late fees.

The eviction court is a debt collection system. The law requires tenants to come up with unpaid rent quickly, or face the Sheriff in a matter of weeks. The system is labyrinthine and inaccessible to most people. Evictions are masked from the internet, so you have to show up in-person to learn about your case. Due to budget cuts, all eviction cases in Alameda County are held at the Hayward Hall of Justice, which is hard to reach by public transit. In the accelerated “unlawful detainer” process, there’s no room for mistakes or missed deadlines. One-third of evictions in Alameda County are “summary judgments” without a hearing or trial, and because of the huge volume of evictions, four out of ten cases in California are decided by a clerk typing a judgment into a computer. If you lose, the unpaid debt can be sent to a collections agency and reported to the credit bureaus. This creates a dual punishment: you must leave your home, with an eviction record and a credit score that disqualifies you from housing elsewhere.

The housing system is built on cycles of displacement. In the 1940s, hundreds of thousands of people migrated to California to find work in the booming war industry. There wasn’t enough housing, and families were crowded into tent camps, abandoned storefronts, and chicken shacks. Workers settled around centers of industry, like railyards in West Oakland and auto factories in East Oakland. Non-Whites were prohibited from owning land in most areas, so they moved wherever they could find space. Some workers at the Kaiser shipyards lived in a segregated housing project at Codornices Village (now called “University Village”), and others settled near a garbage dump in the North Richmond outskirts. San Francisco’s Fillmore district became a sanctuary for Black families after Japanese families were removed to internment camps. Segregation was law, and wartime migration shaped California’s Jim Crow ghettos.

After the war, cities tore down overcrowded buildings through “blight removal” and “slum clearance” programs, causing mass evictions. Shipyard boomtowns like Richmond and Oakland demolished wartime housing for non-White families, clearing space for private housing and industry. Richmond was once connected to Berkeley by a railway carrying workers from Codornices Village—but White supremacists protested that Albany was becoming “like South Berkeley,” and the federal government razed the projects. At the same time, many White families used racially-restricted federal mortgages to build suburbs outside the cities. BART tracks and freeways sliced through the ghettos to clear commuter channels to the suburbs, destroying thousands more homes.

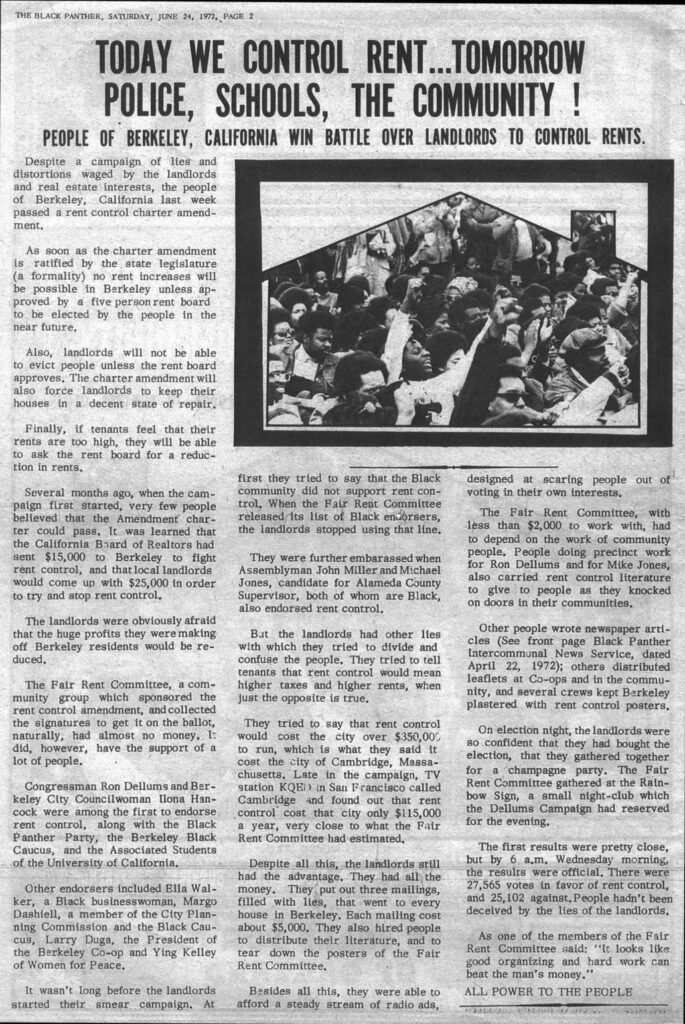

Bobby Seale lived in Berkeley in the 1950s before he formed the Black Panthers in 1966: he went to Berkeley High and moved to Oakland after his family was forced to leave Codornices Village. In Berkeley in the 1970s, young people radicalized by Black Power and the war in Vietnam organized to fight rising rents, as a booming population swallowed the housing supply. Tenant unions led rent strikes to protest dilapidated housing. The Black Panthers joined with Black business owners and the Berkeley Black Caucus to support a referendum vote on rent control. The property owners spent heavily on propaganda to convince voters that rent control would result in higher taxes and rents—but the Fair Rent Committee had strong community support, and propaganda of its own. In June 1972, the rent control referendum passed by a slim margin of 52 percent ‘yes’ to 48 percent ‘no.’

Berkeley was the first city in California to pass a rent control law. The real estate industry reacted quickly: they sued the city and the California Supreme Court voided the law in 1976. Two years later, the same real estate interests pushed Proposition 13, an amendment to the California state constitution freezing increases on property taxes—a sort of “rent control” for property owners. Housing prices were rising so fast that people were getting taxed out of their homes. Ronald Reagan recorded radio ads telling voters the proposition would protect the “American Dream” of home ownership. A hidden motivation was halting a Supreme Court ruling to redistribute tax dollars from wealthy zip codes to underfunded schools. Proposition 13 passed easily: within one year, city tax revenues were slashed in half.

When cities lost property tax revenue, commercial property developers were rewarded handsomely. City governments depend on private capital to finance new developments. Investors decide to loan money for construction based on a building’s expected income: if the projected rents are too low, lenders will not put up the money to start building. The real estate market is structured to generate maximum rents; there is no room for “affordable” housing in this formula. If a city decides to build housing, it must spend money every year on maintaining schools, libraries, parks and other things that communities need. By contrast, shops, restaurants, and hotels earn money for the city from sales taxes, and don’t require any public investment in the community. City planners created more commercial zones and approved more profit-making commercial buildings instead of housing, and rents kept rising.

Berkeley declared a “housing emergency” in the 1980s, and the city passed a “rent stabilization” law to restrict rent increases to the inflation rate; similar laws followed in several California cities. In response, real estate lobbyists passed a statewide ban on rent control. Under the Costa-Hawkins Act, landlords could raise the rent on vacant units to any price; in newly constructed buildings, landlords could raise the rent while a tenant was still living there. The rent control ban was intended to increase landlords’ potential income, thus creating greater incentive to build and rent new properties. In theory, more housing supply would lead to lower rents. In practice, the law had the opposite effect. Waves of workers migrated into the region during the boom of Silicon Valley. Not enough housing was built, and new units were only affordable to high-income tenants.

As rents in Berkeley exploded over the past thirty years, property owners had a strong motivation to evict tenants and raise rents to the “market rate.” Eviction lawsuits in Berkeley are filed with the Rent Stabilization Board, an office established in 1980 to enforce the city’s rent control law. The Rent Board created registers of tenancies and vacancies, and calculated the maximum rent ceiling for every housing unit in Berkeley. After the Costa-Hawkins Act banned most rent controls, the Rent Board’s main functions were mostly eliminated. Today, it acts as a mediator in disputes between landlords and tenants. Like the court system, it maintains an illusion of neutrality between two unequal classes. Behind the front, the Rent Board profits from rising rents: it collects millions of dollars in fees from landlords, most of which goes to paying its own salaries.

Jay Kelekian, the executive director of the Rent Board, worked in the department since its early days in 1984. He became one of the city’s highest-paid employees, earning nearly a quarter-million dollars a year plus benefits, the highest salary of any department head in proportion to their department’s budget. Kelekian’s individual salary was larger than the city’s annual grants to the legal aid organizations for services to protect tenants from eviction. After one of Kelekian’s employees accused him of harassing and retaliating against her, he retired with a large pension in 2020. The Rent Board eventually spent more than $300,000 to hire outside lawyers and settle the case. The Alameda County civil grand jury audited the Rent Board in 2011 and called it “a self-sustaining bureaucracy that operates without effective oversight and accountability.” 300 called it the “Rent Hoard.”

300 believed somebody at the Rent Board was helping cover up Sagwa’s extortion plot. In December 2016, 300 tried to file a registration form with receipts proving Kareem’s rent was $450 per month. The Rent Board refused to process the form. On June 5, 2017, he tried again. The Rent Board refused again. This time, they called Sagwa: a few hours later, Sagwa filed his own registration form. Until that day, Sagwa hadn’t registered a unit in his building in many years. Sagwa’s new registration form matched, exactly, the fraudulent $2,250 lease in his lawsuit against 300. The form declared five people living under a “group lease” and it was signed and dated “March 1, 2015.” The landlord had cooked up a form with false information, and forged the date to look like it was signed in 2015. The Rent Board stamped it “Received” on June 5, 2017.

Sagwa’s registration form was an obvious forgery. The Rent Board sat on the paperwork for four months without processing it into the official record. Then, in October, 300 filed a formal claim against the city, accusing the Rent Board of “fraud, conspiracy to commit fraud, discrimination, harassment, racketeering, [and] false accounting.” On October 19, 300 presented a copy of his apartment’s rent ceiling record to the City Council, proof that Sagwa’s registration form was “missing”—the executive director’s signature was on the document, and 300 accused Kelekian of covering up the landlord’s fraud. The very next day, October 20, the Rent Board processed Sagwa’s forged paperwork and added it to the public file. The city rejected 300’s claim without an explanation.

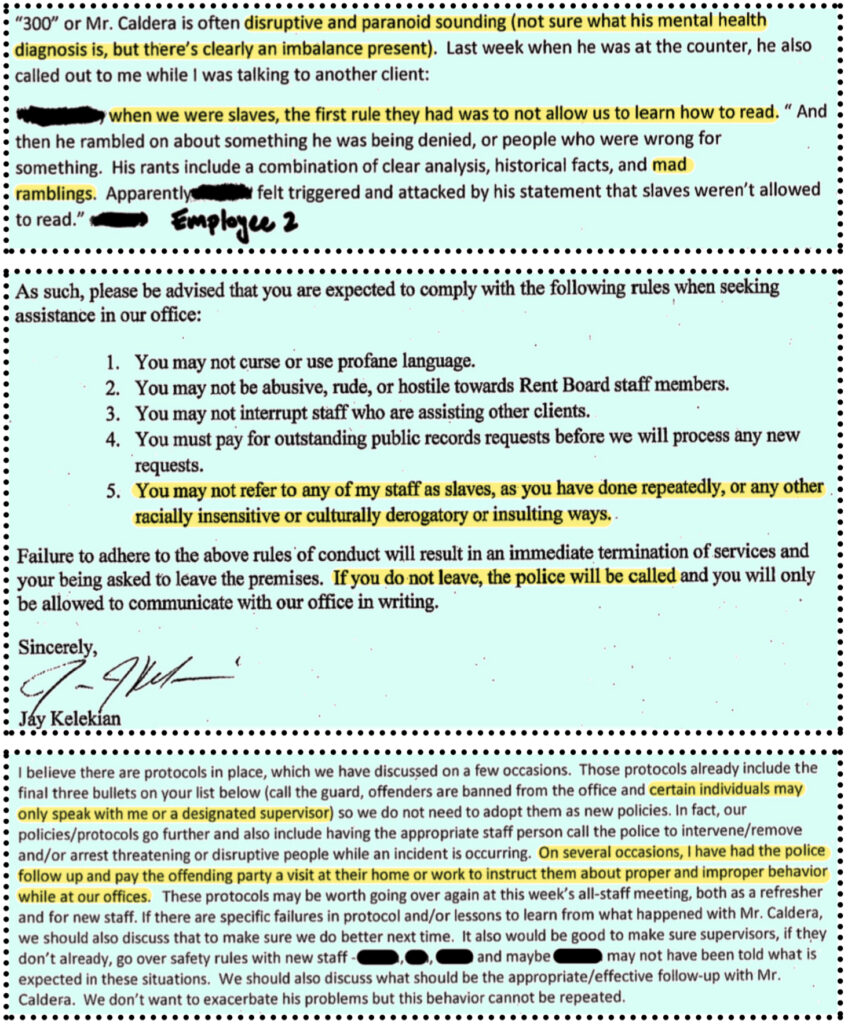

300 filed a Public Records Act request to obtain Rent Board documents related to his case. He discovered that the Rent Board was discriminating against him behind the scenes. In internal department emails, Rent Board employees described 300 as “irrational,” “disruptive,” and “paranoid-sounding.” Mirroring the landlord’s language, Rent Board staff claimed 300 may be “unstable” and “unsafe.” A counselor repeatedly told 300 he was “crazy,” and refused to accept his paperwork. Unsurprisingly, 300 lost his temper. The counselor wrote in an email to the executive director: “I think aggressive people like this who do not carry the bare minimum of respect for our office, should not receive the full scope of our services.” She claimed 300 had “significant mental health issues.”

When 300 raised his voice out of frustration, the Rent Board clerks accused him of being “menacing” and trying to “intimidate” the staff. After a staff meeting in February 2017, Kelekian wrote a letter to 300 threatening to call the police if he returned to the office and acted “hostile.” He accused 300 of wasting the Rent Board’s time and resources. He demanded payment for public records, even though 300 had no income. In an internal email, Kelekian considered sending the police to 300’s home to instruct him on “proper and improper behavior” at the Rent Board. Kelekian told his staff to ignore 300 if he came in. 300 said: “When I would go in there, nobody would talk to me: they’d just stare at me like I was some kind of giant ‘bug.’ I would get frustrated because I was basically treated like I did not exist.”

Kelekian’s letter created a profile of 300 as dangerous and “crazy.” In the letter, he demanded that 300 stop calling Rent Board staff “slaves.” The demand made 300 sound like a racist; it referred to an out-of-context remark 300 had made to a Black employee. 300 asked her: “Do you remember the days when they used to tell the slaves they were not allowed to read and write?” She responded: “Of course. If they taught the slaves to read and write, they would have risen up and they would have had power.” 300 said: “Exactly, and that’s why I’m being treated so badly here.” 300 explained the comment in a testimony to the eviction court:

My comment was trying to point out that it is literacy that is the only thing that has sustained me in my life, throughout all the misery I have experienced. I am a very literate person. I am not saying that I am the smartest person in the world, but my literacy kept me alive on the streets for nearly a decade, and it has kept me in my home over the past year. But at the Rent Board, I am treated as though I cannot read, as though I cannot understand the law, as though I can simply be dismissed or brushed aside because I am poor—like I am some kind of degenerate subhuman or, as [a Rent Board counselor] has repeatedly called me, a ‘crazy’ person.

300’s mother, Sandra Aida Parsons, was descended from Irish settlers and African and Indigenous slaves. She was born in Philadelphia, where her grandparents settled from the South after the Civil War. Her parents were schoolteachers in Philly, and they came to California at the end of World War II. She grew up in Richmond and moved to Berkeley as a teenager in 1960. Following her parents, she became a high school English and journalism teacher at Mission San Jose High School, and she instilled in her children a great love for reading and consciousness of their history. 300’s father was a White man from Oakland whose grandparents emigrated from Portugal in the late 1800s. 300 had never met his father but he resembled him. He once joked that if his mother, he, and I were all sitting together, a passerby might think I was her son instead of him. When other kids asked 300 and his twin sister if their father was White, their mother told them to reply: “Our father is God.”

In 1970, when her twins were two years old, Sandra Parsons bought a small craftsman house by the corner of Bancroft Way and San Pablo Avenue, in a redlined district in Southwest Berkeley. According to 1980 census data, the region west of San Pablo Ave was one of the poorest areas in Berkeley, where one in three people lived on income below the federal poverty line. 300 told cold stories about those days. Dope dealers and pimps ran the block, and crime and desperation were the rule. 300’s mother worked hard to protect her children from violence in their neighborhood. She enrolled them in a private Catholic school and they spent long hours at the public library. Sandra sang gospel hymns at their Episcopal church, and her kids followed her passion for music. 300 used to say his mother had “the voice of an angel.”

The city started offering loans for home improvements in South Berkeley, as part of a program to rehabilitate broken-down houses. To receive a loan, the owner put their deed into a trust for the City of Berkeley, so the city owned the house if the debt wasn’t paid. From 1976 to 1980, 300’s mother took construction loans of a few thousand dollars to repair her house. By 1988, she was still struggling to pay her debts, and she fell victim to a predatory lender. A Los Angeles-based firm called Univest Corp. was targeting poor homeowners with high-interest loans they knew the borrowers could not pay. Most banks refused to loan money to these zip codes, so victims had no choice but to borrow from Univest, at interest rates as high as 16 percent. Brokers forged documents and lied about terms to get signatures on paper. When Sandra accepted money from Univest to pay her debts to the city, the deed of trust was transferred to her new creditor. The bill came past due, and Univest foreclosed on her house. 300’s family was evicted in 1991.

The eviction industry is built to systematically remove groups of people designated as “undesirable.” Since the 1940s, a perpetual housing shortage has enabled cities to depopulate poor people and replace them with a more profitable class. Four years after 300’s family was stripped of their land, the con was exposed: Univest’s fraudulent, “high-risk” loans were a front for a multi-million dollar Ponzi scheme. Many other families lost their homes to these rigged games. Empty houses are bought by wealthy migrants and shell companies. The blocks west of San Pablo Avenue and Bancroft Way, which were seventy percent Black when 300 moved in 1970, are less than fifteen percent Black today. 300’s mother bought her plot of land for twenty thousand dollars. Fifty years later, it is valued at more than one million dollars. A stranger lives in the house they built; Sandra Parsons and both her children have passed away.

Enjoying this story so far?

Street Spirit needs your help. Make a donation of $20 or more and receive a bound and illustrated copy of “The Eviction Machine” as our way of saying thanks!

5. BLOWING THE WHISTLE

Fighting the eviction was an everyday struggle. 300 left at dawn and rode BART with his red leather luggage case to Hayward to file papers or attend hearings early in the morning. When a court date was coming up, I rode my bike to Ghost House to help 300 with his paperwork. My grandma packed snacks and groceries, and my uncle cooked dinner for us to eat while we worked late into the night. Those nights were a clinic in legal tactics: 300 taught me about obscure housing regulations, criminal codes, and contract laws. He told stories about befriending clerks at the courthouse who helped him finesse the system. He said at the courthouse it matters “who you know,” more than the words written on your papers. On the night before a court date, he didn’t sleep: he stayed up until the copy shop opened, printed his papers, then went straight to the BART station.

Sagwa left notes on the door threatening to switch the locks when 300 was gone. 300 was effectively under “house arrest,” and he was afraid to be away from home for too long. Instead of being outside and on the move, he now spent his days isolated and confined indoors, with KPFA playing from his stereo at all hours. Since he couldn’t go to libraries or cafés for internet access, I bought him a cheap netbook and an iPhone 5 with a Cricket data plan. It was his first computer of his own and he was learning to use it slowly, but he was fast at doing research on the phone. He worked tirelessly on the case, studying the laws and sending emails to city officials. He’d cross the street to the 7-Eleven to swipe EBT for groceries, then dash back over the median. He asked friends to house-sit on Thursday evenings, so he could go to City Council meetings and ask officials to intervene in his case.

I had no interest in attending a City Council meeting, but 300 sometimes asked me to come for public comment and yield my time so he could speak longer. He seemed to know everybody in the room, and he had a clear view of each one’s intentions. His friend Carol Denney described the first time she met 300 at City Hall: “We stood in the back and he pointed out every player and whose pockets they were in.” He had a flair for theatrics; he once delivered a passionate soliloquy about storage lockers for unhoused people while wearing an ornate, red feathered masquerade mask. Another time, he helped his friend Marcia Poole demand rain shelter by holding an umbrella over her head.

300 often accused Berkeley’s political clique of hypocritically speaking for the most vulnerable people in public, while working for the most powerful businesses in private. He addressed politicians by their first, middle, and last names, and he called out the money interests they represented: John Caner of the Downtown Berkeley Association, Patrick Kennedy of the Panoramic Interests development firm, and the Lakireddy family of the Berkeley Property Owners Association were on 300’s long dossier of perpetrators. He spoke against the “revolving door” of private developers, like Mark Rhoades, the former Planning Department head who started a consulting firm to shepherd projects through the bureaucracy he helped create. 300 said the City Attorney works in fear of retaliation from politicians who break the law: “If someone on the Council says ‘I want a pepperoni pizza,’” he joked, “the City Attorney will give them what they want, because that is their job.”

Former Berkeley mayor Tom Bates frequently targeted 300 for being “uncivil” at City Council meetings and tried to remove him from City Hall. Jesse Arreguín picked up this habit, and he often accused 300 of breaking City Council rules of conduct. Carol Denney described to me the dynamic between 300 and the inhabitants of City Hall: “They treated him as though he was a threat. And whatever his angry moods might bring, he was not someone you could legitimately call a threat.” She understood 300’s righteous anger at the city’s callous treatment of unhoused people: “Even I have difficulty not getting upset, talking about day after day letting people sleep behind dumpsters,” she said. “There are people in every park we have, just trying to get through one more day. When do we shout?”

Cheryl Davila, the representative for District 2 in Southwest Berkeley, was the only person on the City Council to speak up for 300. In 2016, Davila was fired from a citizen commission after she proposed divesting city funds from Israel’s occupation of Palestine. The censorship incident inspired her to run against the City Council representative who fired her, and she narrowly defeated him later that year. She met 300 when he was sleeping outside the cop shop, and she used to say with sincerity that she only won the election thanks to 300’s endorsement. Davila’s son, Armando, went with 300 to the Rent Board in September 2017 to demand that they process his paperwork. With Davila’s help, 300 was finally able to file a petition asking the Rent Board to recognize him as a tenant.

It is unusual for an eviction to last longer than a month, let alone a year. Sagwa’s paperwork was filled with lies: every time 300 pointed out a contradiction to the court, Sagwa’s lawyer had to come back and explain it, or file a new “amended” lawsuit to cover it up. 300 meticulously documented the pattern of fraud and forgery, and he threatened to report the attorney to the State Bar of California for “subornation of perjury.” By November 2017, with the evidence of fraud piling up, Sagwa’s attorney finally removed herself from the case—but Sagwa quickly hired a new law firm, a team of two eviction attorneys in Oakland’s Dimond District. The eviction clock kept winding down. 300 had exhausted all of his defenses and the court was demanding an Answer to the lawsuit in ten days.

300 refused to file an Answer to the lawsuit. He believed filing an Answer would validate Sagwa’s extortion plot as a legitimate legal dispute. By now, the unpaid rent on the fake lease racked up to almost $30,000. 300 couldn’t afford to lose at trial and get stuck with the bill.

300 was confident he could convince the court to investigate the landlord. He kept telling me about a special motion, a “Motion to Strike,” that could turn the tables on the case. We searched online for a long time, but couldn’t find anything useful. I was losing faith that the Motion to Strike really existed. It was November, and I was in my final semester at the university; I was behind on schoolwork, and I had to study for exams. I pleaded with 300 to file an Answer, go to trial and hope that a jury would hear the truth. But 300 refused to give up. Then, at the eleventh hour, buried in a footnote in the California Judges Benchguide, the judges’ reference manual for eviction cases, we found it: the “Anti-SLAPP Special Motion to Strike.”

The “Anti-SLAPP” law is a free speech protection for whistleblowers. The law was partly inspired by a lawsuit from the University of California accusing activists of “masterminding riots,” an attempt to stop demonstrations against the privatization of People’s Park in Berkeley. A “Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation” (“SLAPP”) is a lawsuit with no evidence to support it, used as a method of harassment and intimidation. Defendants in non-criminal cases are vulnerable to SLAPP suits because they are not entitled to a free public attorney: the goal of a SLAPP is to stick the whistleblower with unaffordable legal fees and the stress of going to court, to get them to shut up and drop the issue. We searched Google for an example Special Motion to use as a template, and got to work.

We had only a few days to write the Special Motion before the court ruled against 300. To file an “Anti-SLAPP” motion, the defendant must be engaged in “protected speech” or public “petition activity,” and they must prove the lawsuit was filed to silence them. His Rent Board petition and his statements to the City Council were the foundation for the free speech argument. The landlord’s response to the Rent Board petition was one sentence long: “William Caldeira is not my tenant.” Sagwa was caught in a double-bind: he told the Rent Board that 300 was not his tenant, to stop the city from investigating the building; but he told the eviction court that 300 was his tenant, so he could get the Sheriff to remove 300 by force. There was a clear paper trail showing a pattern of retaliation.

We documented every piece of fraudulent paperwork. We collected testimonies from other tenants at the building who backed up 300’s story. Kareem had returned to his home country, but he e-mailed a signed statement declaring that 300 was his roommate, and he affirmed that their lease was $450 per month.

On the night before the court deadline, I skipped one of my exams and went to Moffitt Library to print and organize all the documents. The work dragged on for hours, and I was distracted by a pretty girl working at the front desk; I dashed out of the library and asked 300 to write down her name so I wouldn’t forget. We ate tacos on Telegraph and celebrated our achievement, while 300 offered me some avuncular advice about women. He stayed up until sunrise, proofread the documents at Copy World, then made his way to the courthouse.

300 filed the 275-page Motion to Strike on November 28, 2017. We joked that he had “dropped a bomb” on the case. The landlord’s lawyers immediately mailed five fat envelopes to Ghost House, filled with dense legal jargon demanding “production of evidence” and “form interrogatories.” They were trying to force the case to go to trial, but their paperwork was sloppy, and it was an obvious desperation move: they forgot to change the text from the last tenant they sued, and some unfortunate woman’s name was written all over the forms. The court, which had been pushing for a trial as fast as possible, now decided to postpone the hearings. The landlord started demolishing the hazardous wooden structures around the building. 300 met a tenant advocate at City Hall who started accompanying him to the courthouse and the Rent Board. The Rent Board paid a lawyer from the Eviction Defense Center to represent him. And in December, the Rent Board finally held a hearing to determine if 300 was a tenant.

At the Rent Board hearing, Sagwa brought a copy of a fake contract: a blank lease for $2,250 per month, with the same false tenant names listed on the lawsuit. It had no signatures. The Rent Board hearing examiner asked Sagwa why nobody had signed the lease. Sagwa spoke through a Cantonese interpreter and refused to answer questions. He said “Talk to my lawyer”—but the lawyer didn’t show up. When 300 asked him why he was demolishing parts of the building, he said: “I am the landlord. If I want to tear down the building, that’s none of his business. I can do whatever I want” 「我想做什么都行」. Sagwa insisted that 300 was “dangerous” 「他危險」. The hearing examiner was not convinced. He ruled 300 was a tenant based on Kareem’s signed statement, and the rent was $450 per month based on Kareem’s rent receipt. Now recognized as a tenant, 300 filed a new petition demanding the Rent Board investigate the landlord’s illegal rental scheme.

Sagwa left the Rent Board hearing in a fit of fury. He fired the eviction lawyers and brought on his lawyer from Chinatown, one of the team of attorneys who represented him when he was investigated by the IRS. I got a phone call from 300’s lawyer in December, and we spoke about the Special Motion. He hadn’t read the paperwork yet, but he promised to. He sounded friendly on the phone. I was relieved that 300 finally had someone to represent him—the next month, I made a plan to travel to visit my family and friends overseas. I gave the lawyer my email, Skype, and WhatsApp contacts, and asked him to reach out if he needed help with the case while I was away. But I never heard from him again.

While I was out of town, I got frantic emails from 300: the lawyer wasn’t answering his calls. The judge had ruled against 300, in a recorded message played back on the court hotline. The judge gave a feeble explanation that Anti-SLAPP motions must be filed within ninety days of the start of a lawsuit, and 300 had missed the deadline. It felt like the judge was just trying to make the case “go away.” 300 was given a hearing date to contest the decision. He had a strong argument in his favor—because of the special importance of “free speech,” the law says you can file SLAPP papers late if you have a good reason. And 300 had a good reason: he’d been fighting the case without a lawyer. But now that he was represented by an attorney, all his paperwork had to be filed and signed by the lawyer. 300 needed help to contest the ruling, and the lawyer was nowhere to be found.

We knew the court would try to kill the motion on a technicality, and I had discussed this very scenario with the lawyer on the phone. I dismissed 300’s panicked emails about the lawyer’s disappearing act, and I told him to trust that the lawyer would come prepared to the hearing. I was wrong. The lawyer showed up to the courthouse with nothing. When given a chance to speak, he “yielded the field” to Sagwa’s lawyer. 300 was blindsided. The judge demanded that 300 file an Answer, and set a date for the case to go to trial.

After tossing away 300’s main leverage in the case, the lawyer told 300 he would not represent him at trial unless he came up with the money to pay the landlord. In order to win an eviction case, the balance of rent due must be paid into the court. If they calculated the rent at $450 per month, 300 needed more than $6,000 for thirteen months since the eviction began in October 2016. He had not earned any money at all while fighting the case full-time. The lawyer gave him an ultimatum: sign a settlement agreement or represent yourself at trial.

When it came time to give the Answer, the two lawyers and the landlord went into an empty room in the courthouse and left 300 alone in a crowded hallway with the tenant advocate. They returned with a hastily written settlement agreement. The agreement was written on a boilerplate fill-in-the-blank form, and sections of the contract were scribbled like a doctor’s note. It waived the money that 300 “owed,” but it increased his rent to $2,250 per month, forced him to withdraw his Rent Board petition, and sealed the case from public record.

300 had no choice. He wasn’t prepared to defend himself at trial, where a loss would mean tens of thousands of dollars in debt to his name. He signed the settlement in the courthouse hallway.

I returned home in February, a few days after the settlement was signed, and 300 broke down how the case had fallen apart. Since I left town, the tenant advocate who had helped 300 at the Rent Board was now acting as a go-between from him to the lawyer. She was a member of the Alameda County Developmental Disabilities Council and she worked as an adult caregiver. She had no legal qualifications, but she was given the title “Law Clerk” in the lawyer’s office so she could handle 300’s case. 300 accepted her help because he needed help, and he was treated better at the Rent Board when she accompanied him. But she was helping 300 because she believed he was “mentally disabled”—and she had explained it that way to the lawyer.

The lawyer was dealing with his own problems: his wife had recently divorced him, and she took the house with her. He needed to pay his own rent bill. The Rent Board had given him a flat fee of $3,000 to take 300’s case. He was on vacation when the court ruled on the Special Motion, and the tenant advocate was handling his emails. He was no friend to 300, and he had already been paid.

6. THE POLITICAL MACHINE

The settlement agreement gave 300 a written contract validating his tenancy, but his rent was now multiplied by five: from $450 to $2250 per month. The contract required him to cancel his petition for the Rent Board to lower his rent, and the Rent Board ended its investigation into the landlord’s rental scheme. The eviction case was permanently “masked,” and the evidence was removed from public record. 300’s lawyer cut all ties with a blunt message: “I have done what I could, and way more than I have been paid for.” The way 300 saw it, the Rent Board had paid the lawyer to destroy his case.

The lawyer never answered my calls or emails. I don’t know why he didn’t defend 300’s motion. I imagine he was jaded after working for decades in a court system where most tenants ultimately lose their homes. 300 wrote in his court testimony that the legal aid organizations “essentially churn tenants through a machine” and leave them to fend for themselves. He called the legal aid system a city-funded “eviction mill,” a trap where poor tenants are given generic, fill-in-the-blank forms and set up to lose in court without an effective advocate. In 300’s eyes, the Rent Board was openly profiteering from the cycle of evictions and rising rents.

But 300 still didn’t give up hope. The settlement agreement provided a small rent discount until the apartment was repaired, and he raised some money through a GoFundMe page. That bought him a few months. He began researching ways to invalidate the settlement agreement. He kept going to City Hall every week to make his voice heard. Recognizing 300’s determination, Councilmember Davila appointed him to the city’s Committee on Homelessness, which met once a month at the North Berkeley Senior Center.

300 became a Homeless Commissioner just as Berkeley mayor Jesse Arreguín began advancing his new homeless policy, the Pathways Project. In March 2018, Sophie Hahn, the District 5 representative for North Berkeley, attended the Homeless Committee to drum up support for Pathways. The meeting got heated. It quickly became clear that Pathways did not provide permanent housing and it called for intensified criminalization of tent encampments. The temporary housing it did provide was usually somewhere outside Berkeley. 300 claimed the Pathways program was a way to “purge” Berkeley of anybody who lost their housing. He accused Hahn of being disconnected from the issues of people on the street, because she lived in a multimillion-dollar mansion in North Berkeley. The next day, 300 got a call from Davila; Hahn and Arreguín were demanding she fire him from the Homeless Committee. Davila refused.

Berkeley’s Pathways program was modeled after San Francisco’s “Navigation Centers,” facilities with short-term beds, health services, and a promise of housing. Placement into the Navigation Centers is combined with systematic destruction of tent camps, to force unhoused people out of certain neighborhoods. Encampments receive an eviction notice before they are “resolved” (a euphemism for “demolished”). These resolutions are merciless; a case manager for San Francisco’s Homeless Outreach Team told me about a Public Works officer who threw a dog into an industrial trash compactor with belongings seized from a tent. One homeless outreach worker resigned in protest and sent a mass email to San Francisco officials describing the encampment sweeps as “cruel” and “re-traumatizing.” Most people placed in a Navigation Center end up back in the streets. This creates a “churn” from shelter to crisis, forcing people to rebuild their camps and start again. The outcome for many is losing hope of ever finding housing.

Homeless advocates and activists in Berkeley called for sanctioned encampments to protect tents and belongings from confiscation and “resolution.” But the Homeless Committee meetings went nowhere. Many committee seats were left empty, commissioners were disinterested and disengaged, and they couldn’t reach the minimum number of votes. A former commissioner who worked with 300 told me: “It seemed like the city intentionally kept the committee understaffed so we couldn’t get things done.” The city maintains citizen commissions to keep up the appearance of public participation—meanwhile, decisions about government policy are made elsewhere.

300 called Berkeley’s government a “political machine” greased by real estate interests and the University of California. For almost four decades, a small clique of Berkeley politicians have moved through a revolving door between the Berkeley City Council, the State Assembly, and the State Senate—former mayor Tom Bates, his chief of staff Dion Aroner, his wife Loni Hancock, and her campaign manager Nancy Skinner. Bates was a Democrat operative from the Ronald Reagan era who engaged in petty election crimes, like postage schemes to circumvent campaign finance rules, and trashing copies of the newspapers that endorsed the opposition. Bates cultivated an influence machine in Berkeley, where city officials “rubber stamp” decisions made in handshake deals over expensive dinners.

The city government’s agenda is to advance the development projects of commercial property owners and the University of California, who jointly profit from the flow of wealthy students admitted to the campus. Although UC Berkeley is a public university, it receives more funding from private donors and corporate sponsors than from the state of California. UC administrators believed Tom Bates, a university alumnus, could help navigate local politics and make the city a more attractive environment for corporate investment, especially from the technology industry. Bates arranged deals that gave the UC control over major downtown development, and shuttered old factories in West Berkeley to make way for the university’s outer orbit of startup satellites. He encouraged property owners to form a political action committee to promote real estate interests in local elections. In 300’s words: “This town is a real estate market with a university attached.”

Tom Bates oversaw the creation of “business improvement districts,” commercial property owners that pool their money toward political campaigns and shape the city’s agenda behind the scenes. A major focus of the business improvement districts is removing unhoused people from public spaces. In the mornings, their hired guards roust anybody sleeping outside shops before they open. During the 2012 election, the CEO of the downtown business district paid unhoused people to distribute fliers for a ballot initiative that banned sitting on sidewalks—the leafleters thought they were working for Obama, but they were being paid to criminalize themselves. In 2015, the City Council made it illegal to lie down on cement benches or park a shopping cart on the street. As 300 often said: “It is a crime to be poor in Berkeley.”

In Berkeley, money buys political influence. When 300 asked the mayor for help fighting his eviction, his case was handled by Jesse Arreguín’s senior advisor and co-author of the Pathways proposal, Jacquelyn McCormick. McCormick was a former executive at Bank of America who managed corporate real estate, and her husband was a senior executive at Morgan Stanley. They lived in an enormous mansion in the Uplands, less than one mile from the Jim Crow “Whites-only” sentinels on Claremont Ave and Hillcrest Road. McCormick tried and failed to run for mayor in 2012, then became volunteer treasurer for Arreguín’s 2016 election campaign. McCormick was very effective at fund-raising. An investigation by the Fair Campaign Practices Commission found that she had made thousands of dollars of illegal contributions to Arreguín’s campaign from her personal credit card. After the election, she was named Arreguín’s “point person” on homelessness, despite having no experience with housing issues.

The city investigated the mayor’s illegal campaign contributions through one of its ceremonial citizen commissions. During a six-month-long investigation, the meetings of the Fair Campaign Practices Commission weren’t covered by the local media. The vice chairman of the commission had been appointed by Arreguín and he refused to recuse himself despite an obvious conflict of interest. 300 was one of the only members of the public to attend the meetings, held in a small classroom at the North Berkeley Senior Center.

Arreguín and McCormick appeared before the commission in June 2018. As usual, the meeting was sparsely attended. During the public comment, 300 called the mayor a “career politician” and asked the commissioners to treat Arreguín as they would any other citizen. He argued that punishing Arreguín with a small fine simply proved that money buys privileged access to the political machine:

We are dealing with someone who believes they are above the law. We are dealing with someone who has a tremendous amount of political power, political backing, and money. I believe this is a sham meeting. This government does not have the power to review itself. This government does not have the power to monitor itself. I’m very disturbed that we have people from the Berkeley hills who believe that city government is something for them to play with. Every single time, it’s always someone from the Berkeley hills who decides they’re going to get their ‘toe in the bathwater’ of Berkeley politics and do whatever they want to do. Rules are rules, and personally I don’t believe that people can pay money to excuse their bad behavior. This is not about money, this is about ethics. It’s not about paying a fine, it’s about what already happened. It is appalling.

As they awaited the committee’s decision, Arreguín and McCormick exchanged hushed whispers from behind the sheets of paper on which they had printed their prepared statements. As 300 anticipated, the commission disciplined Arreguín with a small fine and a slap on the wrist. The official audio recordings of the commission’s meetings were lost or destroyed. McCormick was promoted from volunteer treasurer for Arreguín’s campaign to Arreguín’s Chief of Staff; 300 called her “the real mayor of Berkeley.”

Many of 300’s predictions about Arreguín’s homeless policy proved true. A small number of people in Berkeley received housing through the Pathways program, but the city wouldn’t provide any data about who was able to keep their housing in the long term. Pathways’ housing placements often resembled 300’s run-down building on University Avenue. One woman was placed in an illegally converted garage in Richmond with no hot water or electricity. She told the Daily Californian: “It’s been a horrible six-month nightmare. My landlord comes over every day without a 24-hour notice. He’s hoping to bully me out.” After she complained to the city, a safety inspector found the unit had black mold, a rat infestation, and no bathroom—so they shut down the garage, and she was back on the street. Mike Zint, the founder of First They Came for the Homeless, told the local CBS station that the city was “working the numbers” to give the appearance of “permanent” housing placements that weren’t really permanent:

If you want somebody to start recovering from everything that’s going on in the streets, you need to give them their own space. They need privacy. They need security of their possessions. They need to be able to come and go as they please. They need to be able to make decisions without any pressure. Instead they’re being shuffled into the first opportunity available so somebody can ‘check’ their name off a list of being homeless. That’s not a solution. These people are going to end up back on the streets at some time.

Zint believed the “permanent housing” numbers were being inflated to secure larger contracts for Bay Area Community Services (BACS), the private non-profit corporation running Pathways STAIR Center: “It’s a game, so that they can get on TV or go to the government and say ‘Look at how successful we’re being. We need to expand this.’” BACS assets grew by tens of millions of dollars in the decade since they began running the housing programs. When an unhoused man gave an interview to CBS News about Berkeley’s false housing promises and “deplorable” conditions at the Pathways STAIR Center, the executive director of BACS sent a letter to its investors questioning the man’s “mental health state.”

Berkeley’s housing policy aligns neatly with the profit motives of property developers. Political campaign contributions give some clues about their agenda. “Super PACs,” independent election propaganda groups, invested in only one 2020 City Council race in Berkeley: Cheryl Davila’s District 2 seat in Southwest Berkeley. In the final month of the race, the California Association of Realtors unloaded more than forty thousand dollars on brightly-colored attack mailers against Davila. The Chicago-based National Association of Realtors Fund spent almost ten thousand dollars on mailers supporting a solar engineer from Georgia. At the time, Davila was proposing a 75% salary increase for City Councilmembers, from $38,000 per year to the county median income, to help lower barriers for poor people to run for office; the fliers depicted Davila as a greedy bureaucrat, claiming “she’s 100% in it for herself.”

The real estate industry targeted Davila because she refused to support new housing developments without a significant number of affordable units. A dark money non-profit called the Housing Action Coalition (HAC) backed both of Davila’s main challengers. HAC is a “pro-housing” lobby funded by the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, the philanthropic foundation of the Facebook founder and his wife. The group promotes policies that subsidize affordable units by charging fees to developers and discounting those fees when buildings include token “low-income” units. The HAC Regulatory Committee was led by an executive from AvalonBay, one of the largest real estate investment trusts in America. AvalonBay owns undeveloped land in West Berkeley and the Avalon Berkeley, a five-story luxury apartment complex near the waterfront. The Avalon building is a typical example of “subsidized affordable” housing: it contains ninety market-rate units and four affordable units.

A few months after Davila lost her City Council seat in the 2020 election, Jesse Arreguín held a video call with the HAC Regulatory Committee to discuss housing policy in Berkeley—a private portal for HAC members only, closed to the public. Influence peddlers typically operate hidden from public view. At a private dinner held by the Berkeley Property Owners’ Association, president Sid Lakireddy reminisced about a time he met Tom Bates at City Hall and the mayor bragged about the huge number of market-rate housing units built during his tenure; Bates asked Lakireddy, sarcastically, “You don’t like me, do you?”