In the beat of homelessness journalism and advocacy, I’m like The Hair Club for Men’s Sy Sperling of my field: I’m not only an expert, but I’m also a client. Specifically, a client of the San Francisco emergency shelter system.

Or that was, until recently. I learned that an employee of the organization that operates the shelter where I was staying since last fall tested positive for the coronavirus. Rather than risk exposure, I left—but not until I found a temporary place where I could exercise some physical distancing and self-quarantine.

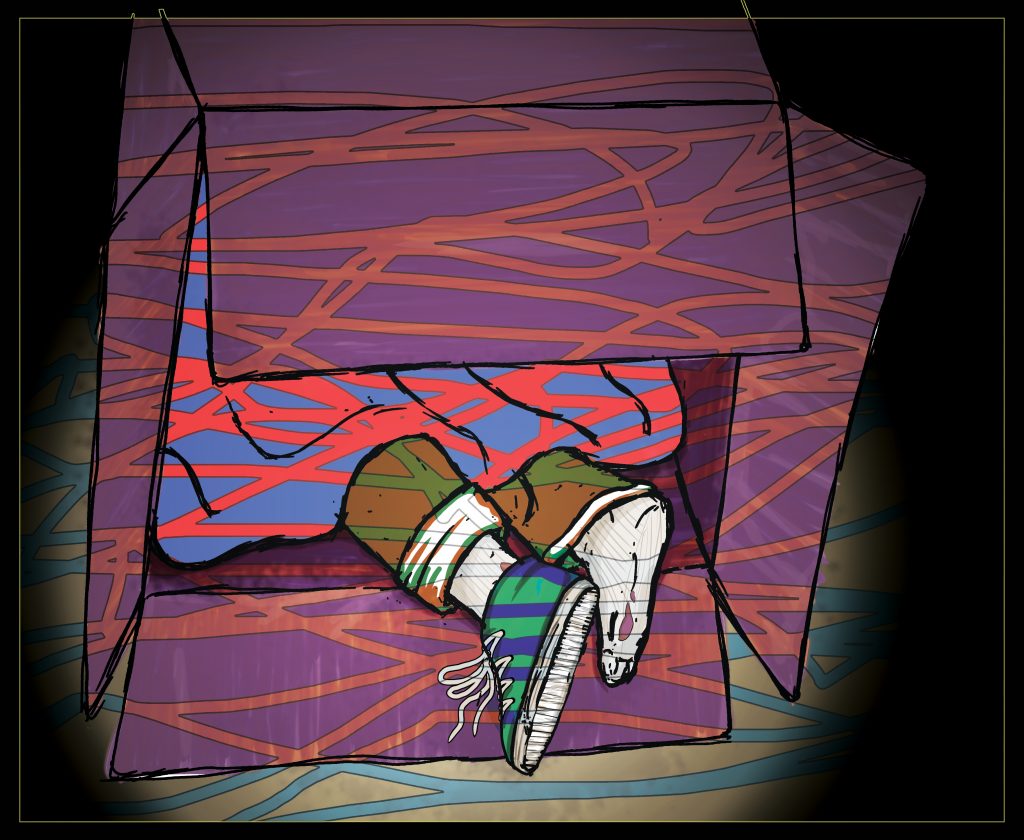

“Sheltering in place” is a privilege that over 9,000 unhoused San Franciscans do not enjoy. Six feet of physical distance has been recommended by public health agencies. Yet, shelters are congregate environments where people sleep barely more than two feet away from one another, head to foot or top to bottom in bunks.

My now former shelter was similar to that, though the degree of congestion slightly differed. Instead of beds sprawling on the same floor like some kind of warehouse—like the shelter where 100 people tested positive recently—the shelter was divided into separate dorms, and the bunks separated by partitions.

It should be noted that being unhoused itself is a pre-existing health condition. Roughly one-third of houseless San Francisco report some kind of chronic health problem, according to the city’s latest point-in-time in 2019. Some of my old shelter mates need a cane or walker for mobility issues, or live with physical infirmity, or carry some level of psychological or emotional trauma.

Researchers at UC San Francisco found almost half of unhoused people experience their first homeless episode after age 50 and most are likely to present health problems of housed people 20 years older. People I’ve shared living quarters here easily represent both cohorts .

Homeless people, especially of advanced age and underlying health conditions, would be hit hard in our current COVID-19 landscape. But those who sleep outside have even less of an opportunity than sheltered homeless people to sequester themselves—no door, no lock and limited access to hygiene. And with 30,000 hotel rooms lying vacant in San Francisco from the unexpected hit to the tourism industry, there is literally more than enough room at the inn.

Our Board of Supervisors unanimously passed an emergency ordinance that would deconcentrate the shelters and give residents their space. So what’s the hold up?

As for our supposed incapacity to live indoors, I think my shelter mates and I could manage in a single-person space after years of congregate living.

Oh, the homeless people don’t want it, and besides many of them are just too dysfunctional. Or at least that’s what the city says. But a sample of unhoused residents offered a rebuttal in a YouTube video. They say they would accept a room if offered, and they would be able to take care of themselves. And based on my encounters with people dealing with substance use and/or mental health issues, I don’t buy that they don’t want or aren’t seeking any services to remedy their problems—it’s just they haven’t been offered anything that works.

As for our supposed incapacity to live indoors, I think my shelter mates and I could manage in a single-person space after years of congregate living. Hell, the philosophy of “housing first” holds that we can more easily focus on ourselves in a place where curfews, restrictions and arbitrary assessments aren’t imposed. It’s not service resistance, it’s wanting appropriate services that aren’t people-resistant—the mats that were laid out in little squares at a downtown convention center were emblematic of such. Last year, I interviewed some 200 of my fellow unhoused peers for a needs assessment study that will be released later this year. The majority of unsheltered people have actually attempted to access shelter and been rejected, or else regularly use shelter when it becomes available only after a weekslong wait. Also in short supply are mental health and substance use treatment programs, particularly those that demonstrate cultural competence among women, non-English speakers and LGBTQ people.

A 53 year-old African American man found housing through case management to be elusive. He needed someone who could guide him accordingly.

“You don’t want to talk to someone who can’t do anything for you,” he said. “You can talk to them about personal stuff, but as far as getting the housing done, you gotta know who those people are.”

Meanwhile, advocates, service providers and medical authorities have been urging San Francisco for weeks to provide suitable lodging so homeless people can abide by health guidelines. In a recent press conference, Rupa Marya of the Do No Harm coalition expressed concern about the city’s approach and tactics around sheltering unhoused people. Marya, a medicine professor at UCSF, has been advocating for securing hotel placements for unhoused people as soon as possible. Succinctly and eloquently, she stated, “A roof over your head is not a prerequisite for humanity.”

Colette Auerswald, a professor at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, echoed Dr. Marya’s sentiment by declaring, “Shelter in place should not be a privilege. It is a human right.”

Now, the city is now following their recommendations, but its delayed response will cost the wellbeing, if not lives, of its residentially challenged locals, like the 100 shelter residents I referred to earlier. If shelter in place is extended beyond May 31—and I imagine it will be—I might have to look for another place. In that eventuality, I have a GoFundMe to cover hotel costs.

After all, how do you shelter in place without a place to shelter yourself?

TJ Johnston is the Assistant Editor of Street Sheet, San Francisco’s street newspaper.