Editor’s note: About a month after we re-published this story, the Berkeley Flea Market re-opened under a revamped leadership team, thanks to a deal with BART.

This story was originally published in Berkeleyside.

This is a eulogy for the Berkeley Flea Market, a largely unheralded institution that for several decades exemplified the values of the city that hosted it.

Its last official day was Saturday, June 28, when the small number of vendors in the Ashby BART Station parking lot offered evidence of the flea market’s gradual decline.

But that should not obscure the expansive vision behind it, and the contributions it made for nearly half a century to the sustenance and soul of Berkeley.

The flea market, which both of us were involved in launching in the mid-1970s, was the brainchild of community activist Pat McClintock as a way to raise funds for over a dozen Berkeley nonprofit organizations providing services from health care and housing to child care and disability rights.

At the time, several of these organizations were struggling to survive, and to get beyond the annual cycle of begging the city council for small grants that often made the difference between survival and shutting down.

We all belonged to Community Services United, a grassroots organization formed to enhance our collective lobbying power and improve our services together. Shortly after its founding, CSU became even more essential as we fought cutbacks resulting from passage of the early tax-cutting Proposition 13 in 1978.

One of us, Freedberg, worked at the Growing Mind School, which enrolled autistic and other students the public schools were unable, or refused, to serve. The other, Lynch, was a CSU staffer who went on to run the pioneering Over 60 Clinic, which evolved into the LifeLong Medical Care under his direction.

Other members included the Center for Independent Living, the Berkeley Free Clinic and early community recycling efforts.

It took months of cajoling by a single-minded McClintock to convince BART to allow the flea market to use the Ashby parking lot.

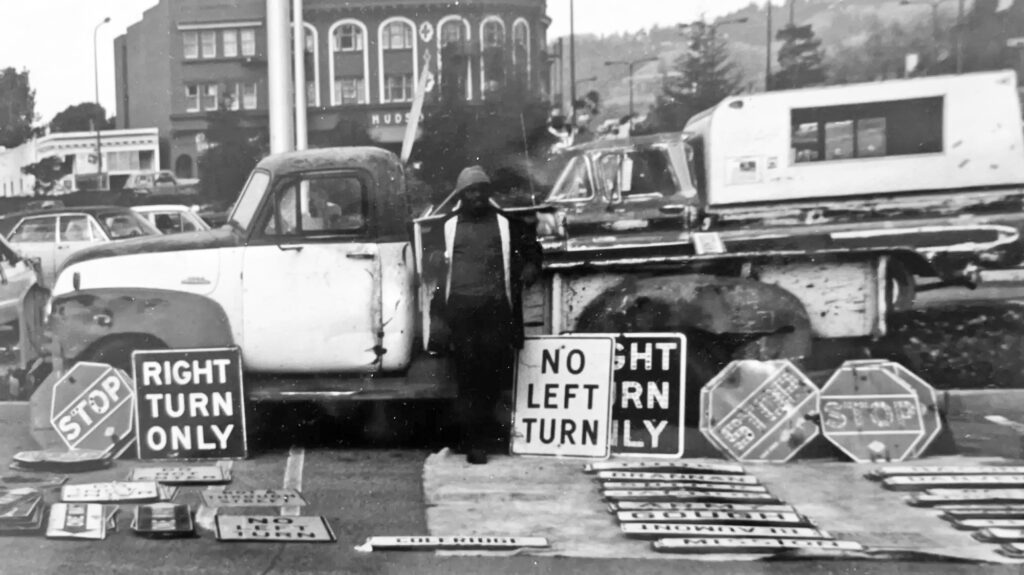

The two of us were assigned the unglamorous task of collecting the garbage every Saturday or Sunday afternoon in Freedberg’s 1950 green Chevy truck. Each weekend we lugged the trash on a pro-bono basis to the vast odorous dump in the still-evolving landfill where Cesar Chavez Park now stands.

While it never raised large sums for community organizations, the flea market became an essential stop for Berkeley residents of all ages seeking low-cost furniture, used clothing and almost anything else. It also symbolized Berkeley’s commitment to locally controlled nonprofits as a way to provide critical services.

Equally importantly, it was a gathering place to hang out for an hour or two on weekends, savor food from the African food truck and others, and listen to drummers like the one simply called Spirit, who has been drumming at the flea market for the last 30 years, and was there until it closed on Saturday.

Several local leaders stepped up to manage the flea market during its early years. Among them was Keith Carson, later a longtime Alameda County Supervisor. Another was Arnold Perkins, a community legend who went on to become Alameda County’s Public Health Director.

While the flea market never achieved the grand presence of the rambla in Barcelona, or the unifying force of the parque central throughout Latin America, it did offer a rare mixing ground for people from different backgrounds, ages, and parts of the city — while also providing assistance to Berkeley organizations serving essential human needs and individuals just trying to get by.

On [June 28], we stopped by to pay homage to the flea market as vendors packed up one last time.

Channeling Berkeley’s impulse for resistance, some vendors said they would keep coming until they were forced not to. Lashone Stowe, who started coming to the flea market as a child, was angry about what he said was poor management in the last few years—and wistful about its loss.

He once lived a few blocks away on Woolsey Street. Even when his family lived in Pittsburg and then San Francisco, he would still come to the flea market regularly with his father.

For the last five years, he has had a stall selling oils, perfumes, and body lotions, which has generated significant income.

“Even if it is gone, it will never be gone for me,” he told us. “This is Berkeley to me right here. And a lot of my customers feel the same way.”

May the communal spirit of the flea market live on in other creative ventures underway in Berkeley or those yet to be spawned — a spirit that will be needed more than ever as the simple but potent concept of “community” comes under attack from the Trump administration.

Louis Freedberg, a veteran education journalist, is executive producer of the Sparking Equity podcast and the Sparking Education Success Substack. Marty Lynch is CEO emeritus of Lifelong Medical Care.