‘When someone is living in the margins, being published matters…’

When I was young, in my twenties, I took pride in being able to get letters to the editor published. For a young adult with severe psychiatric illness, a letter to the editor in a paper is pretty good. But I wanted more. I really wanted to become a published writer. Periodically, I would submit stories to publications, and if you consider the level of the writing I produced back then, I stood little or no chance of getting something accepted.

I married my wife when I was 31. Often, I would drive her places, and I would sit in the car and wait for her. At one point, my wife wanted to visit the animal shelter and spend time with the animals there.

The old animal shelter in the Pacheco area, near Concord and Martinez, was probably built in the 1940s or 50s. It was a flat, unadorned eyesore of a building that shared the same road as a wastewater treatment facility. It made me think of my past incarceration. I later found out, through a television news story, that the animal shelter was in fact a repurposed detention center.

My wife had published some works in Street Spirit, and I envied that. But while I sat in the car in the parking lot of the old animal shelter (long since torn down and replaced), an idea sparked in my mind for an essay about it—a personal essay. Because the animal shelter resembled a detention center, and I had my own set of experiences as someone who has been detained, a story was in the making.

Once the essay was completed, I sent it off to Street Spirit. Terry Messman, the co-founder and editor of Street Spirit at the time, accepted the piece. In 2001, I was finally a published author.

The street papers, for many years, have provided me with a unique opportunity that would be impossible for me to find elsewhere. Sometimes you need an ‘in’ to be published with a newspaper or magazine. My ‘in’ with street papers is that I live with a severe disability, and I am poor as dirt. If I was just another Joe Coffee Bean with no disability, a Starbucks manager by day with literary aspirations by night, street papers would not be where I publish my work. But this is my life, this is my story, and street papers have remained an open door.

Street papers give people like me a voice. I can talk about the hardships of being mentally ill and my inability to do conventional work on a competitive level. Living with this disability often results in poverty, not to mention disrespect. But as a contributor to street newspapers, I can talk about my experiences, I can voice my outrage about how badly mentally ill people are dealt with. I can also speak of and advocate for people who are more unfortunate than me.

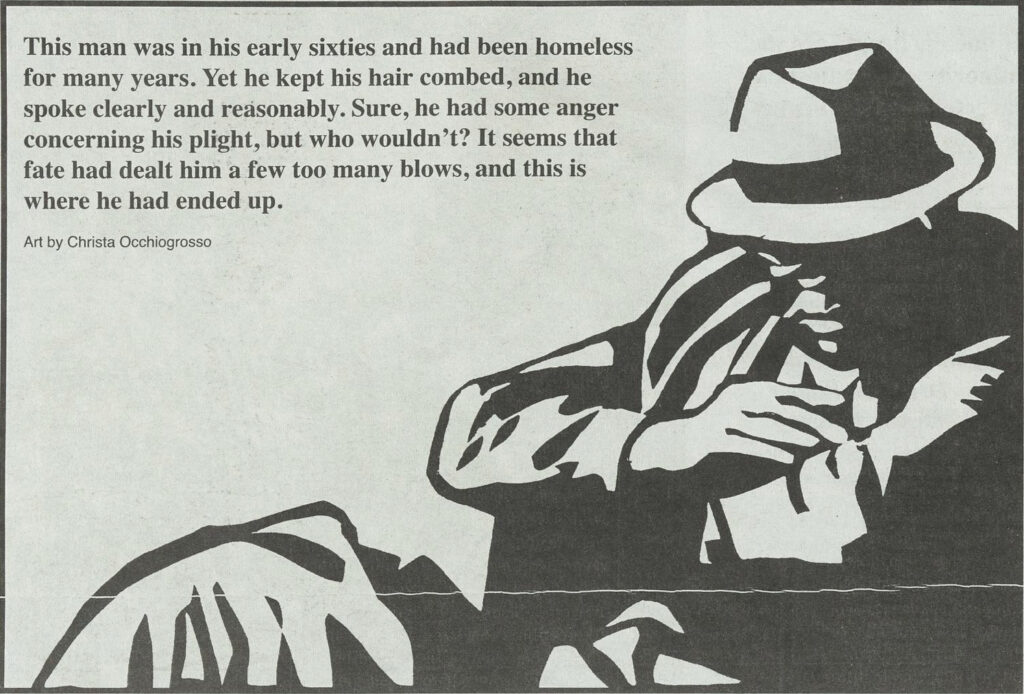

This brings to mind a story I wrote for Street Spirit years ago, entitled “Coffee and Conversation with a Homeless Man.” I was sipping iced coffee and smoking cigarettes at a Starbucks while my wife shopped nearby, and I shared an outdoor table with a homeless man as he ate a sandwich from the nearby 7-11. He asked for one of my cigarettes, and I was happy to part with it. He didn’t know that I was listening closely and thinking of writing a story about him. I didn’t tell him because I feared he would be offended. He believed I was just some guy willing to talk to him, which at its core is the truth of the matter. Too often we avoid unhoused people, see them

as individuals we shouldn’t interact with, and the essay became an example of what it is like—what it means—to share a table with someone you may otherwise ignore.

In the case of Street Spirit and other street papers, it is a win-win situation. Contributors to this paper have the essential opportunity to get the word out concerning injustices and harm perpetrated toward the least fortunate members of society. Writers are able to promote their craft and get paid for their work, which has some potential for conversion to income and a better life. At the same time, readers are allowed an entrance into a world they might not otherwise have access to, let alone understand. Just as street newspapers leave the door open for writers experiencing homelessness, poverty, and mental illness, they also leave the door open for its readers to understand these hardships from the people who experience it first-hand.

When someone is living in the margins, being published matters. A lot. It brings a compensatory factor to a life that might otherwise seem pitiful. And being paid for my work matters. I truly appreciate street papers like Street Spirit, a publication which has given me a chance.

Jack Bragen currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.