From the age of 18 to the age of 30, I was homeless without crime. Every place I slept, every piece of clothing I had, every house or apartment I rented, every car I owned, every meal I ate, all came from money that was illegally gained by me. Hence, without crime I would have been homeless.

Here’s an example. It’s 1988 and there was three motels next to each other: The Comfort Inn, the Snooty Fox and the Mustang Motel, in Los Angeles. I would sell drugs in the daytime and pay for a room at night at either the Snooty Fox or the Comfort Inn.

The Mustang Motel was a different story. It had a night manager who used to smoke cocaine. You know the story, I would trade him a relatively small amount of drugs for a room. The rooms here were $90-$189 a night, but I would trade a $20 rock for sometimes two days of shelter.

Count 1: the purchase of illegal narcotics. Count 2: the distribution of illegal drugs. Count 3: fraud, crime against humanity by feeding his addiction. I was homeless without these crimes.

He was willing to steal from the people that employed him. Worst of all, I was never concerned about what the cocaine was doing to his life, or his children’s lives. The ripple effects.

This was the deeper and more shrouded crime I committed, which I believe is worse than the first. I distributed drugs to people who committed all sorts of crimes to feed their addiction. Everything from grand theft auto to burglary, from institutions of prostitution to spousal abuse (because drug use is one sure way to create a toxic environment).

I once read a passage in which Jesus said, “he has not the place to lay his head.”

I can absolutely relate to that statement. The truth is, Jesus laid his head where he did his good work. The sad truth is, I laid my head where I did crime.

There are several realms of reality that opened up when I chose to commit crime for a living. First, the psychological. I knew and I acknowledged that what I was doing was wrong. It was lawfully wrong, it was ethically wrong, and it was morally wrong. But I was homeless without crime.

Secondly, the pain of aloneness compromised my commitment to goodness and innocence. The lines became blurred and I began to accept a new reality that, “you only get, what you go get.” I started quoting clichés in my mind like, “all is fair in love and war” and, “a lot of cheddar will make it a lot better.” While the lines were blurred, in my mind I was homeless without crime.

Thirdly, crime became my new normal. I accepted crime as a way of life, and the money made everything seem right. Being broke was not an option. But I was homeless without crime.

I was homeless without crime, so I would not let anyone take anything from me by force. Yeah, you know the story. Now I was willing to be violent in the name of self-protection. So yes, I was homeless without crime. However, with crime, I was worse.

I had become deceitful, cunning, a liar, a drug dealer, a robber, a pimp. To my shame, what I did broke up families, ruined individuals lives, caused child endangerment. I was causing homelessness in my community by selling drugs. And I was still homeless inside.

I knew that all the things I had wasn’t really mine. All of the security I had could be taken away in a moment. All the material things never addressed the real problem, which was low self-esteem, bad self-image, no value in who I was as a person, and fear. I could never escape that fear, and the reality that nothing I had was truly mine, no matter how much I had.

I stopped committing crime. But that feeling — the fear of homelessness — still remains.

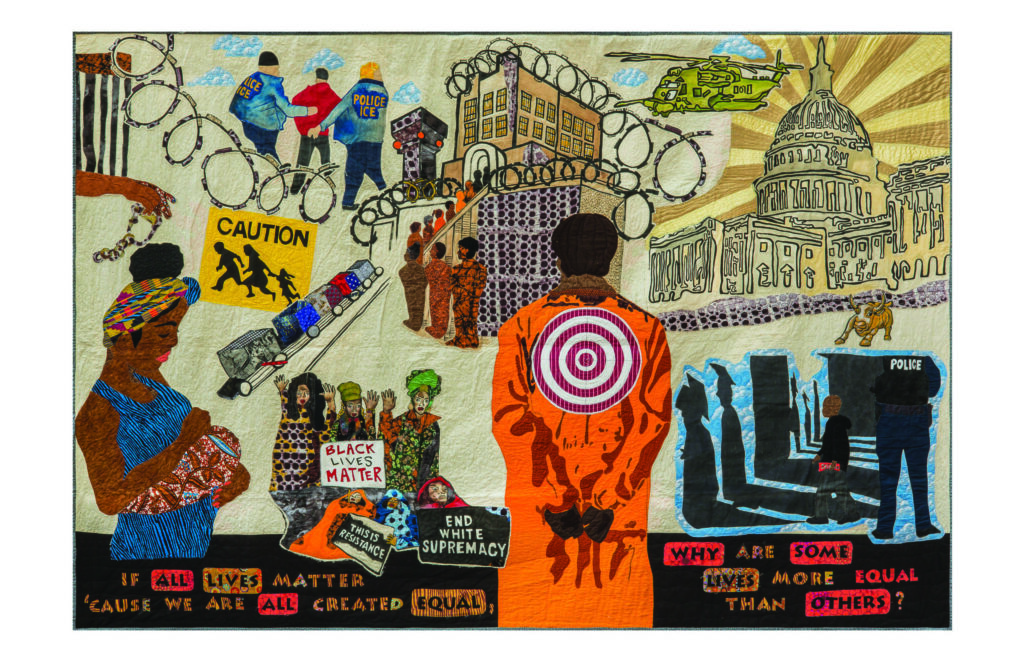

This Cantastoria (picture storytelling with song) uses a handmade quilt to trace the history of the Prison Industrial Complex from slavery to mass incarceration and the killing of Black and Brown people by police. (Dey Hernández, Jorge Díaz Ortiz, and Sylvia Hernández, Justseeds)

Kevin Sample is one of Street Spirit’s vendor coordinators. Outside of Street Spirit, he is working on founding the Lazarus Foundation, a soon-to-be nonprofit committed to food, shelter, and clothing for the unhoused population.