by Carol Denney

A good friend of mine, the best political strategist I’ve ever met, years ago made a wry remark to me that one’s effectiveness at city council meetings was inversely proportional to one’s attendance. But Elisa Cooper, who passed away on June 21 at her home in Berkeley, proved him wrong.

His point was that if you show up at every council meeting and speak on everything on the agenda, you court looking silly.

People do this. They’ll stand at the podium and scream angry questions about agenda items they haven’t researched and don’t understand in front of a city council constrained by the rules of public comment not to answer.

It’s a recipe for making everybody look dumb. It also soaks up time. As the evening lengthens, tempers fray and the odds against elegant policy-making get longer.

But Elisa Cooper did her homework.

She was consistently present for important community meetings, but she brought more than her own opinions with her, so that her short observations were loaded with hard-edged information, offered in her dedicated, elegant activist voice.

It is a terrible loss for us. If you’re a council-watcher, she was among a small handful of activists whose public comments you knew would have nuggets of policy gold.

These activists slowly, patiently bank information in not just the listening city councilmember’s mind, but also Berkeley’s active, voting public.

There comes an arguably precarious point when if enough of the active, voting public can claw its way through the acronyms and bizarre planning department argot and achieve enough understanding about an issue to become immunized, public relations ploys stop fooling them. Robo-calls stop affecting their votes.

Rock-solid, first-source information begins to set the foundation for common sense policy.

People with their ear to the ground of housing policy, like Elisa Cooper, are seeing some of this foundation.

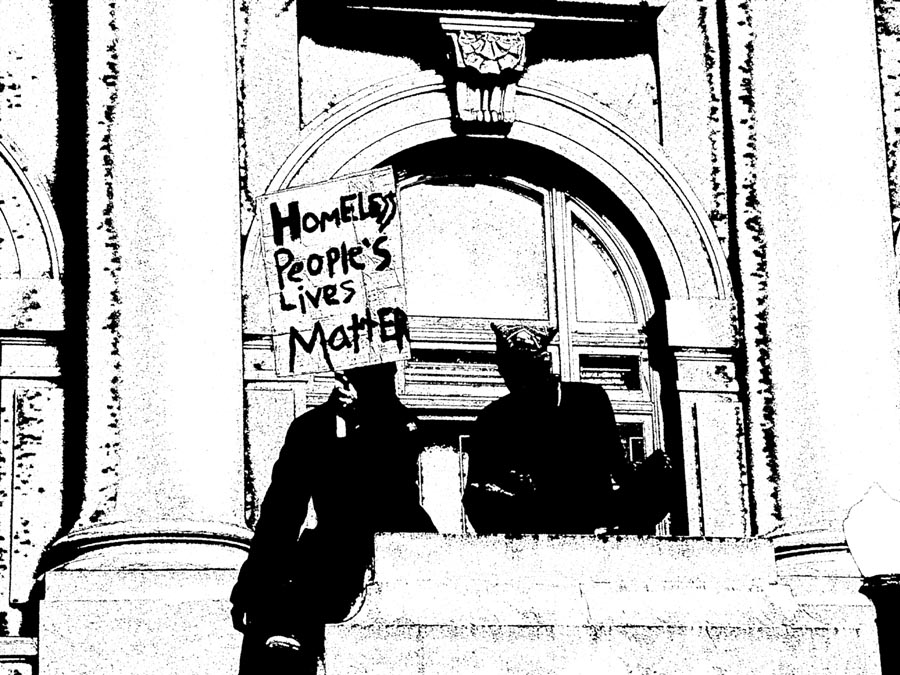

Right to Rest legislation moves a little farther each year.

Abuses of owner-move-in evictions and assaults on habitability standards have at least a few writers and reporters offering excellent coverage for the interested public.

At least some politicians in crucial seats have clarity about the financial and moral bankruptcy of chasing poor people with nowhere to go in circles.

Elisa Cooper was the only voice who stood up at a Berkeley City Council meeting only a month ago and argued against the Downtown Berkeley Association’s contract renewal, which was on the consent calendar, the area of the agenda reserved for non-controversial items.

She pleaded with the council to discuss the DBA contract, and was ignored, which is hard. It is much easier to argue for a losing effort if you have a group working with you and can at least commiserate together.

The DBA is a controversial group, arguably a radical group. The DBA board is dominated by wealthy property owners, and presents even this new council with fresh, unvetted legislation which usually hits the council agenda without bothering to inconvenience relevant city commissions.

The DBA spent years tearing down community posters — a First Amendment violation — until finally challenged. It has no external complaint system for the abuses of its “ambassador” team, even when they are caught on video assaulting homeless citizens.

Its CEO was sanctioned for violations in a campaign to criminalize the poor for sitting down. And if you’re a property owner downtown, you have no way to opt out of membership and obligatory fees.

It has more than a million dollars to play with, a consistently right-wing agenda, and at present the Berkeley City Council expresses no concern about its heavy hand on policy, including their staff in meetings none of the rest of us get to hear about.

Elisa Cooper kept her eye on all of this. She checked meeting minutes to get voting records clear, she did first-source research so she could develop an elegant ear for phrases freighted with self-serving motives. She played a difficult role, an unsung role, in a relatively indifferent community.

Elisa was one of the few who understood the emergence of Business Improvement Districts and their undemocratic nature, and she became one of the most educated local voices on BIDs.

Berkeley City Councilmember Ben Bartlett, representative in her district and still in his first electoral year on the council, sent a note of sadness about her loss after her death to his constituent list.

The phone lines buzzed between bewildered activists who knew her as the person who could grasp the deepest detail and synthesize analyses into clear language.

Elisa Cooper’s voice is one voice at public comment, it is safe to say, that even a council often weary of public comment will deeply miss.

*** *** *** *** *** ***

The Controversy Over Tiny Houses

Commentary by Carol Denney

I have a rueful saying about musicians: “Musicians will eat anything you feed them.” The point, after a lifetime of gigs that either pay nothing or less than minimum wage considering expenses and practice time, is to acknowledge that we’re in it because we can’t help ourselves. Artists with a calling, a much kinder word than obsession, couldn’t stop creating if you paid them.

In the articles about “tiny houses” in Street Spirit in the past year, there appears to be no recognition that tiny houses violate habitability requirements, cost more and reduce green standards. I’ve found there’s almost no interest from those who promote them in organizing for rent control, vacancy and mitigation fees for landlords and developers, or rehabbing older buildings for cooperative low-cost housing, or other more practical responses to the lack of low-income housing.

Our habitability standards are not at fault for our housing crisis, which accelerated when the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act passed in 1995, allowing landlords to raise rents to market rate when a unit was vacated, a change which also had the effect of incentivizing owner-move-ins and evictions.

In fact, the burden you create for people if you force them to live without water, heat, electricity, and cooking facilities is huge. The hide-and-go-seek game played in most towns with restroom availability, for instance, in order to avoid attracting poor people in need of washing out a few things, is documented in the Downtown Berkeley Association’s meeting minutes and policy recommendations. When the new BART Plaza is unveiled, a public restroom will be strangely missing, thanks to their lobbying — with our money. BART’s own restrooms remain firmly locked, still using the tired post 9/11 security hazard excuse.

Tiny houses may not have bathrooms, or kitchens, or heat, or trash receptacles, unless you go for the fully decked-out-like-a-house treatment which rockets the price up so high their promoters turn red-faced, since the whole miniaturization fad rests on overlapping myths of seeming cheap, or green, or habitable. Trying to cook and bathe in a glorified tent without ventilation near combustible materials is not just hard, it’s dangerous, as several local fires in tent cities recently underscored.

Landlords have habitability requirements imposed on them by the city and state so that people don’t die of mold, or hypothermia, or a conflagration like the Ghost Ship fire, while paying rent for the privilege. And Berkeley had lots of cheap housing in the early 1970s. That’s part of the reason People’s Park exists; there was so much cheap housing and office space that the University regents simply found UC Berkeley’s argument that they really needed to build housing or offices or sports courts there unconvincing, and wouldn’t vote them any money to build anything, resulting in a user-developed park.

But the tiny houses band plays on. The usual accompanying theme is that they are better than nothing, and I used to agree. But now I am not so sure. Tiny house promotion has displaced rational approaches to our housing crisis. There’s nothing good about that. Poor people are being shortchanged in the promotion of what is technically and legally uninhabitable under the law, and there’s nothing good about that. Landlords and property owners charge anything they want, get rich, and my colleagues want to ask for less instead of more.

A couple of my friends attended the earliest meetings of Youth Spirit Artworks’ tiny house promotion, and described what they considered the phenomenon of “groupthink” at work, where the desire for conformity and consensus in a group results in what Wikipedia describes as “an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. Group members try to minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative viewpoints by actively suppressing dissenting viewpoints, and by isolating themselves from outside influences.”

Maybe. But the most recent pro-tiny houses article makes it clear that “musicians will eat anything you feed them” is at least a competing guiding principle. The writer, Lydia Gans, points out correctly that when you have nothing at all, anything looks good. And I do agree that in a pouring rain, offering someone who is homeless an umbrella is a good thing. But offering someone an umbrella instead of housing is not a good thing. And charging rent for that umbrella, in my book, is an outrage.

It is easy, perhaps too easy, to have one’s sense of compassion hijacked by the flavor-of-the-month, landlord-driven effort to promote tiny houses as an answer to the housing crisis. But there’s nothing pretty about trying to live in a miniature train set where you accidentally knock over the town hall every time you reach for your shoes. Real human needs, like your shoes, can certainly be miniaturized. But good luck getting those shoes on.