by Terry Messman

The summer of 1967 was a moment in time when a utopian vision of peace and love seemed to be just over the horizon — or even down the next aisle in a record store.

On June 1, 1967, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and seemed to herald a new day when love would overcome the injustices and cruelty of a world plagued by war, poverty and racial discrimination. “With our love, with our love, we could save the world — if they only knew,” George Harrison sang on “Within You Without You.”

Only two weeks later, on June 16-18, 1967, the Monterey International Pop Festival brought together an extraordinary gathering of some of the most creative and innovative musical artists in the world, including Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, Otis Redding, Booker T. & the MGs, Ravi Shankar, Canned Heat, the Electric Flag, the Mamas and the Papas, the Byrds, the Animals, and Country Joe and the Fish.

Taken together, those two momentous events — the Beatles’ imaginative and beautiful album, and the epochal gathering of legendary artists at Monterey — seemed to announce the dawning of a rebellious and visionary counterculture. The first rays of sunlight in the darkness of a world at war.

It now may seem like a half-remembered fragment of a dream, but those days were filled with the hope that momentous social change might emerge suddenly from almost any protest, and breathtaking moments of beauty could be found in almost any music store or concert hall.

It’s easy enough now to ridicule the 1960s counterculture, and cynically reject those bygone hopes of social change. But I never surrender to that cynicism. For, in the midst of the cruel injustices of the Vietnam War, and in an era marked by napalm and hydrogen bombs, widespread hunger in America and brutal attacks on civil rights demonstrators, a new generation of musicians began singing about peace and love, and a new generation of activists launched a rebellion against war and social injustice.

It may have been a lamentably short season of peace and love, but it was utterly beautiful to see those values blossom seemingly everywhere.

For one of the few times in our nation’s history, a generation rejected war and greed, and declared that love was the supreme value. “A Love Supreme” proclaimed John Coltrane in his classic 1965 album. “All You Need Is Love” the Beatles sang in 1967. Love in action was the new form of social change pioneered by the civil rights movement and then embraced by the peace movement and the counterculture.

Today, the countercultural visions of peace and love seem as distant as “strange news from another star,” in Hermann Hesse’s phrase. Yet in 1967, strange news from another star — the strange message of love and kindness and revolutionary change — could be seen on evening newscasts or heard on car radios. That’s what the records of Country Joe and the Fish evoke — the imagination and hope of the 1960s.

In his interview with Street Spirit, Country Joe McDonald described the significance of that era. “It was important for me to be part of the Aquarian Age,” McDonald said. “I don’t know how to describe it, except that it was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, stuff happened in London, stuff happened in San Francisco and BOOM!

“Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. And it really happened. I don’t know how or why it happened. But it was a wonderful thing to happen.”

Epiphany in a Record Store

In December of 1967, the winter after the summer of love, when I was in my early teens, I walked into a music store and the sight of three wildly imaginative new records struck like the force of revelation. I still play them to this day: Disraeli Gears by Cream, Magical Mystery Tour by the Beatles, and I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die by Country Joe and the Fish.

Those surrealistic and riotously colorful album covers amazed me at first sight. An epiphany in a record store. The flowering of the counterculture.

The cover of Disraeli Gears exploded in swirling psychedelic images of day-glo orange, magenta and pink, and the songs inside — “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” “Strange Brew,” “Sunshine of Your Love” and “SWLABR” — merged the surging electric blues guitar of Eric Clapton with the mind-expanding excesses of psychedelic distortion.

The Beatles album was even more wondrous: I saw stars, technicolor stars. And walruses. My favorite artists on the planet had undergone bizarre transformations into walrus, hippo, rabbit and bird, and the magical word “Beatles” was written in yellow stars in an ocean of multi-colored stars. The cover art absolutely knocked me out with its imaginative re-visioning of the Beatles, and the album included my single favorite song of all time, “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

The album’s other brilliant songs — “I Am the Walrus,” “All You Need Is Love,” “Penny Lane,” “Fool on the Hill” — expressed the deepest dreams of the counterculture. John Lennon’s anthem, “All You Need Is Love,” was the perfect song for the Summer of Love, and made a deep impact on the world. The whole world was watching when the Beatles performed it live on June 25, 1967, for an audience of 400 million people in 25 countries on a broadcast of the first live global TV program.

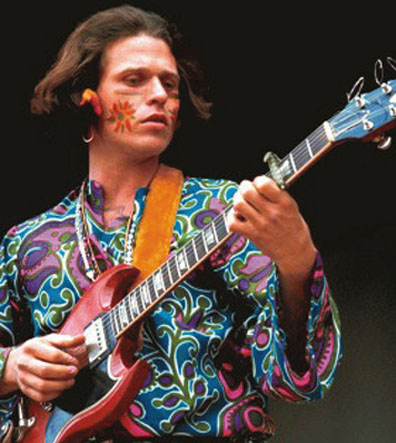

Already floored by Cream and the Beatles, I next saw the madcap cover of I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ To Die, with Country Joe and the Fish posed in a parody of Sgt. Pepper’s. The Beatles’ technicolor band uniforms were mocked by Fish finery: the cigar-chomping Chicken Hirsh in a beanie cap topped with propeller, David Cohen casting a spell as a tacky-looking sorcerer, Barry Melton in a Civil War uniform, Bruce Barthol with an apple stuffed in his mouth, and Joe McDonald as a peasant revolutionary with sombrero and rifle.

The three albums were entrancing — revelation in a record shop. A world that had been trapped in gray conformity suddenly had become a place of dazzling enchantment. It felt like the winds of change were breezing through the store.

Those images and that music left a lasting imprint — symbols of the spirit of peace, love and beauty in the 1960s.

Greater Acclaim for the Fish

Today, the ongoing critical re-evaluation of the music of the 1960s has greatly elevated the musical reputation of Country Joe and the Fish. The band is now more highly renowned than ever, and their first two albums have won new acclaim as under-rated masterpieces.

In AllMusic.com, noted music critic Bruce Eder gave extremely high praise to their first album, Electric Music for the Mind and Body, calling it “one of the best-performed records of its period, most of it so bracing and exciting that one gets some of the intensity of a live performance.”

Eder added, “Their full-length debut is their most joyous and cohesive statement and one of the most important and enduring documents of the psychedelic era, the band’s swirl of distorted guitar and organ at its most inventive.”

In The Mojo Collection: The Greatest Albums of All Time, the Fish’s first two albums were ranked among the finest of all time. Mojo called their first album “extraordinary acid rock excursions” and said it remains “one of the few truly successful U.S. psychedelic albums.” Describing their second record, Mojo wrote that the Fish had become “the Bay Area’s foremost psychedelic adventurers, dizzyingly blending acid rock, satire, revolutionary politics and mischief.” And Mojo called the title song, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die,” “a satirical, anti-war masterpiece.”

In Musichound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, Joel Selvin and Ken Burke wrote, “A largely forgotten giant of psychedelic rock, Country Joe and the Fish towered over their contemporaries, and left behind one masterpiece album — Electric Music for the Mind and Body — one of the definitive albums of American acid rock.”

‘The People’s Rock Star’

Country Joe and the Fish disbanded at the end of the 1960s, but McDonald went on to make music that carried on the spirit of the ‘60s. In 1969, he released Thinking of Woody Guthrie — in my mind, the finest tribute album ever recorded of Guthrie’s music.

Backed by some of Nashville’s best musicians, McDonald’s vocals bring Guthrie’s populist songs to life in beautiful and deeply felt performances, sometimes spirited, sometimes plaintive. His Guthrie album showed the connections between the social justice spirit of the 1960s and Guthrie’s rebels and outlaws and ramblers and Dust Bowl refugees — the common people fighting for justice.

The radical left-wing British musician Billy Bragg said, “Like no one of his generation, Country Joe McDonald carries on the mission of Woody Guthrie.”

Long after the 1960s, McDonald carried on with songs of social protest, singing out for peace at benefit concerts, speaking out against war and nuclear weapons, showing up for environmental causes, championing fair treatment for military veterans, homeless people and the victims of war.

Joel Selvin described McDonald insightfully: “He was there at strikes, protests and picket lines as much as nightclubs and rock concerts. He was the people’s rock star with his own booth at the Berkeley farmer’s market. Honest, humble, unbought, unbossed. Woody Guthrie would have understood Country Joe in a heartbeat.”

Country Joe’s Benefits in Berkeley

Daniel McMullan, an advocate for homeless and disabled people, had loved Country Joe’s music when he was young. Decades later, after he moved from New York to Berkeley, he was inspired to see McDonald upholding those ‘60s ideals by supporting homeless benefits and protests.

“I first heard Country Joe McDonald as a kid,” he said, “when my older brother brought home the original Woodstock soundtrack with ‘Rock and Soul Music,’ the Fish Cheer, and ‘I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag’ by Country Joe McDonald. We played it all the time, and we thought it was the funniest thing. We used to love that album, so he was like a hero of mine.”

After McMullan moved to Berkeley, he became homeless and got involved in activism. While organizing a concert in People’s Park for the Medical Marijuana Initiative in 1996, he asked the Woodstock icon to perform. “I had thought I’d never be able to get him to play because he was a hero of mine. But I called him up and he was the nicest guy. I told him about the concert and he said, ‘Sure, I’ll come play.’”

The benefit in the park turned out to be a very large concert, with 10 bands playing. “Country Joe’s performance was great,” McMullan said. “He was the last to perform, and by the end, the police were getting all crazy, and trying to shut it down and unplug the sound. The whole crowd was outraged when they tried to unplug it!

“And Joe just kept playing along. It was so great! He was like, ‘Don’t worry, we’re not going to let them stop the electricity. Just keep going.’ He finally did the last couple songs acoustically. It was just really fun to see that.”

Berkeley activists held a month-long sleep-out for homeless rights in 1999, and won several concessions from the City, including a rain shelter for stormy weather. When City officials kept delaying the rain shelter, McMullan helped organize a fundraiser called Shelter from the Storm.

“I called Country Joe and once again he comes to the rescue and agreed to play,” he said. “He was great and he was the hero of the show. He played some really cool acoustic stuff, and played a flute, and it was amazing. It was a night that people would never forget. He was just so gracious and nice and funny.”

The Arnieville Encampment

In May of 2010, McMullan joined East Bay activists in organizing “Arnieville,” a tent city on a traffic island near the Berkeley Bowl that was set up to protest Gov. Schwarzenegger’s budget cuts to social services for poor and elderly people and In Home Supportive Services. The organizers held a concert for the homeless and disabled people staying in the tents.

“People were amazed that we got Country Joe to come out to Arnieville,” McMullan said. “I really thought his performance at Arnieville was one of his best.

“The people were so scared about their lives and what was happening with cuts to In Home Care and elderly care. In Arnieville, people could come together and at least feel like they were fighting back.

“And to have Country Joe there fighting back with us — it doesn’t get any better than that. I really want to give Joe his props for all the times he showed up.”

Street Spirit’s in-depth look at the music and the man: Country Joe MacDonald.

Country Joe: Singing Louder Than the Guns (April 2016)

Country Joe McDonald stands nearly alone among the musicians of the 1960s in staying true to his principles — still singing for peace, still denouncing the brutality of war.

Songs of Healing in a World at War (April 2016)

Country Joe McDonald’s songs denounce the atrocities of war and pay tribute to Vietnam War combat nurses and the legendary icon of mercy, Florence Nightingale, for bravely bringing medical care into war zones.

Carrying on the Spirit of Peace and Love (June 2016 Issue)

Country Joe McDonald has carried on the spirit of the 1960s by singing for peace and justice, speaking against war and environmental damage, and advocating fair treatment for military veterans and homeless people.

Street Spirit Interview with Country Joe McDonald Part 1 (April 2016)

Women coming home from the Vietnam War never were the same after their wartime experiences. They were shoved into a horrific, unbelievable experience. That’s what I wrote about in the song: “A vision of the wounded screams inside her brain, and the girl next door will never be the same.”

Street Spirit Interview with Country Joe McDonald Part 2 (April 2016)

“It was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, London, and San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. It was a wonderful thing to happen. And I’m still a hippie: peace and love!”

Interview with Country Joe McDonald, Part 3 (June 2016)

“We’re still struggling as a species with how we can stop war. The families (of Vietnam veterans) were so grateful that anybody would acknowledge their sacrifice. And I don’t mean sacrifice in a clichéd way. The war had reached out and struck their family in a horrible, terrible way.”

Interview with Country Joe McDonald, Part 4 (June 2016)

“I knew a lot of the people had to escape or they were killed by the junta in Chile. It was just tragic and terrible. I had grown up with a full knowledge of the viciousness of imperialism from my socialist parents. So I knew that, but I was still shocked.”