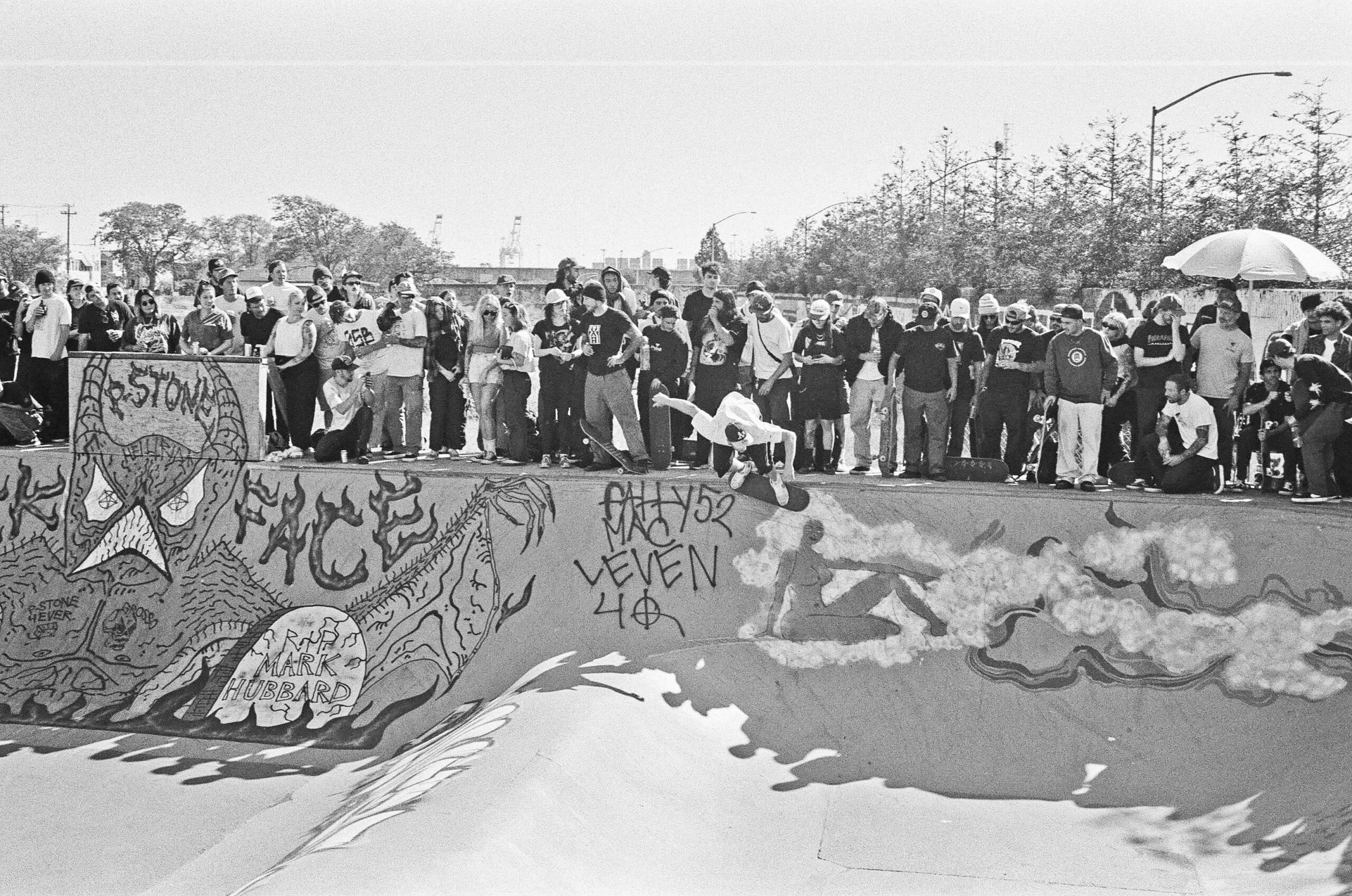

Skaters participate in the annual P-Stone Cup: a DIY skate show at Bobs that draws skaters from around the world. (Big Hongry)

This story originally aired on KALW. Listen online, here.

Bobs is an unlikely oasis at the bottom of Ninth Street. It’s pressed up against the retaining wall between the Lower Bottoms neighborhood and Highway 880. It’s over 7,000 square feet of concrete anarchy: smooth, steep walls and big ramps, covered in colorful graffiti that shines in the sun. I never thought concrete was beautiful until I saw Bobs. Skating, it turns out, changes the way you see things.

That’s Big Hongry. He helped build Bobs back in 2013, when it was just a vacant patch of concrete.

“You look at stuff differently when you start skating. This is just a curb to someone who doesn’t skate. But if you skate and you see a nice curb, you’re like, I could have so much fuckin fun on just this curb,” Hongry says.

Kids are frequent visitors at Bobs. (Big Hongry)

“Before we came down here though, this lot was just empty and filled with like old needles, and dirt and trash and clutter,” says Hongry. “There’s a video somewhere, of like, us with a couple of the kids from the neighborhood, who eventually kept coming to learn how to skate. They uh, helped clean up all the stuff and put it in a bag. I mean it was like, treacherous, treacherous. This place wasn’t nothin down here, at all. It was kind of like that story of taking trash and turning it into gold.”

That shift in perspective he got from skateboarding? It’s not just about the way he looks at concrete. It’s part of his value system.

Colorful artwork adorns every inch of Bobs—here’s just one view of the park. (Alastair Boone)

“Skateboarding is hella cool for that aspect of like, humanizing people. You know like, you’ll be skating some cutty ass spot under a bridge or somethin, and there’s someone who lives there. And now you’re here, and like, this person like, is here every day, every night,” says Hongry. “And you get to meet them and like, they become part of the family. Because they’re like, ‘Oh, the homies are going to be at my crib when I get back, building some shit, let me bring some stolen meat, or let me bring some beer that I bought,’ or some random shit. And now you’re chopping it up with this homie who you would have never talked to. Through skateboarding.”

Hongry is a co-owner of Break Free Skate Shop in Downtown Oakland. For him, and the folks who skate Bobs, skating is a conduit for community. In the early days of the park, it was just a bunch of guys — with bags and bags of concrete.

“A couple cats who knew exactly what to do, and a couple cats still trying to figure out what to do, aka me,” he recalls. Some didn’t know how to use a shovel.

A skater takes the bowl at the P-Stone Cup. Crowd goes wild! (Big Hongry)

“And you’re learning. You’re learning techniques, you’re learning patience — cause you gotta put the concrete down and you gotta step back, you gotta let it dry, because if you keep fucking pecking at it, it’s gonna lump up…that was the crux of it all was just: we’re starting something new, if you’re down, come through,” he continues.

They never exactly pulled the permits to build a skatepark. There were a few meetings with city officials early on, but those never came to much. Hongry figures after ten years, the park’s credibility speaks for itself.

“Bobs got a common law marriage with the streets of Oakland,” he says. “We tapped in.”

Bobs isn’t the East Bay’s only DIY skatepark, but it quickly became a mecca for a certain kind of skating. It’s fast and dirty, with big scary ramps that make even seasoned skaters’ palms sweat. Much of the park is built from scavenged material: A telephone pole becomes a spine, debris from the area becomes fill for the ramps. And they’re always adding to it and changing things.

“It’s concrete, and dirt, and rocks, and love and sweat and blood, maybe a couple cigarettes, and then concrete on top of that,” Hongry says.

Julio Pineda skates at Bobs for the excitement and release.

“…getting loose, blowing some steam, blowing some weed, literally getting close to the edge of these obstacles, seeing how far you could take it, trying not to get too hurt, but keep going when you get too hurt,” Julio says.

“And that’s life,” Hongry adds. “Try not to get too hurt, but keep going if you do get hurt.”

It’s allegory, but it’s also simple.

“Just going fast and [loud sound, laughing] that beautiful noise,” Julio says.

For some people, Bobs is more than a skate park.

“Right now it’s home, unfortunately…But, you know, so. Just a place I’ll always have to go.”

Construction currently blocks off the entrance to Bobs on 9th Street, so skaters must enter through this secret door in the retaining wall next to Highway 880. (Alastair Boone)

That’s Russ. He lives at Bobs these days. He sleeps under an overhang beneath one of the skate ramps.

“It is what it is. I definitely choose this. They have a bed for me in the city but, you know, I’m choosing to stay here instead…For the home feeling.”

Russ unfolds a letter, with an offer for a shelter bed circled in black pen.

“Maybe tomorrow I’ll try it out…I’m bed number 154, on 5th street,” says Russ.

Russ sets up next to a fire pit, covered in cigarette butts and mosaic tiles. The tiles sparkle in the cool pit, spelling out the names of people who have passed on— who died too young and left their mark on the scene. It’s spiritual, like a reliquary, or a hot fire on a cold night.

“The reality of it is, stuff’s hard in the city, stuff’s hard in the country. Stuff’s hard everywhere and people just want to get away and do something different than have pain. And like, some of the stuff that makes you feel the best is the stuff that can make you die the fastest,” Hongry says. “Whether it be alcohol, drugs, or whatever. I think people are just looking to escape, really, especially during now, during these times.”

And Hongry says, Bobs is a welcome reprieve.

“That’s why skating is cool though, because you get to just tune out of that and you get to just roll around and you know for sure…If you hold it down for your homies, if you go early, if you go late, the homies are going to hold it down for you no matter what. They’re going to put it on T-shirts…there’s justice in your death. It’s not just like a lost cause you know. We understand.”

But change is coming. A new housing development called “The Phoenix” will soon butt right up to the skate park.

A representative from the development company told me the new housing won’t displace Bobs. But even if it does impact the culture of the park, Hongry isn’t worried.

“We’ll just go somewhere else, you know. It’s whatever, you know. It’s no way to get around certain shit in life. But I mean I don’t think that’ll happen honestly. I think if they smart they’ll leave it there.”

A phoenix is a symbol of resurrection. The bird rises from the ashes of what came before. That might be what the housing development is called, but there’s already a phoenix here. The spirit of Bobs lives in the people who use it — it can’t be contained to a single place.

Alastair Boone is the Director of Street Spirit and a beat reporting fellow for KALW covering homelessness.