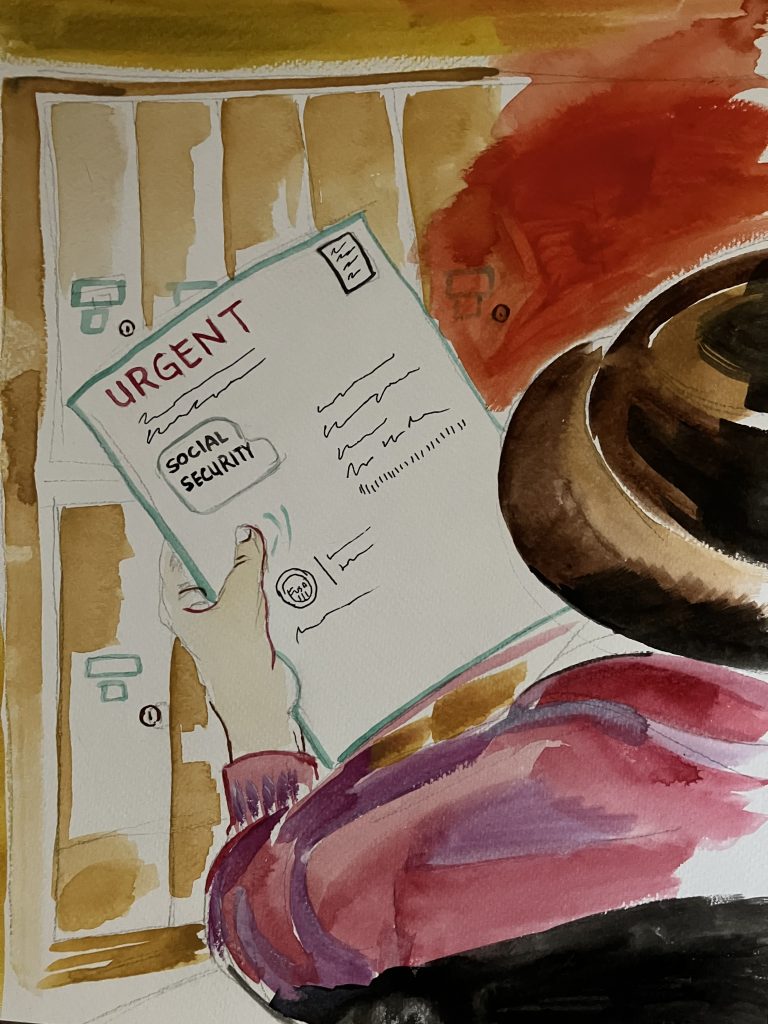

For three decades, I have relied on Social Security benefits to put a roof over my head, to put food in my belly, and to provide much needed medical care. I have valid, documented reasons that I am entitled to these benefits. However, for over a year, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Social Security Administration sent me harassing communications, threatening to cut me off should I fail to comply with their demands. Sometimes they asked me to fill out complicated paperwork and mail it back to Social Security prior to deadlines, and in other instances, the demands were to show up for mandatory appointments. They demanded a great deal of information, some of it to be supplied by me and some by the professionals involved in my long-term treatment—people who already have access to my charts. Given the fact that my disability benefits are crucial to my survival, this felt like a life-or-death struggle. I was terrorized. I discovered in my research that I am not alone. I spoke to a Social Security attorney who told me this is happening to thousands of disabled people in the U.S. In a January 2020 Huffington Post article titled “Trump Administration Quietly Goes After Disability Benefits,” Arthur Delaney reported that this is the result of a policy change wrought by the Trump Administration. Just before he left office, Trump instituted sweeping changes to the way the many receive disability benefits. Among these changes, Delaney writes, the government began looking “more closely at whether certain disability insurance recipients still qualify as ‘disabled’ after they’ve already been awarded those benefits. While recipients already have to demonstrate their continuing disability every few years, the proposal would ramp up the examinations, potentially running still-eligible beneficiaries out of the program.”

Delaney’s article completely corroborates my own experience. It began for me in the year 2020. I received a sixteen-page questionnaire. I filled this out with as much thoroughness as I could muster, and I was fully truthful. I foolishly thought at the time I’d be done and would hear back. What I got was a year’s worth of repeated demands for information, culminating in psychological and physical evaluations conducted in remote locations by practitioners who’d been hired directly or indirectly by Social Security. The examinations are performed by psychologists and medical doctors tasked with assessing whether or someone is “faking” their disabilities. By happenstance, I have seen employment ads for psychologists boasting that doing these interviews is very lucrative.

The appointments were far off the frequented track and conducted by clinics I’d never heard of. Some of these locations seemed so odd that I did research beforehand to make sure I wasn’t being kidnapped by a criminal faction of the government. That’s how badly this process stoked my anxiety. I was receiving letters for appointments that threatened to cut off my SSDI, SSI, Medicare and Medicaid if I didn’t comply with the demands.

To give you an example of the distress, I was at the physical component of the evaluation, and when they took my blood pressure, it was 160 over 100. This is a potentially deadly level of hypertension—normal blood pressure is about 120 over 80.

If you are disabled and independent, it is very hard to comply with the demands of these reviews. The rigor and frequency of their communications implies that they are geared to assess people who do not handle their own affairs and who are getting helped by a third party. Secondly, they seem geared to assess those who are not severely disabled. If we were too disabled and on our own, we would be unable to clear all of these careless hurdles.

For example, one of these appointments required me to drive or take public transportation to a morning appointment in downtown Oakland at rush hour during the rainy season, which was very difficult due to my agoraphobia and difficulty to drive long distances. My mom and her husband offered to drive me, yet they, at the time, were in the middle of medical crises themselves. I was able to talk some sense into the individual in charge of my assessments and convince him to move the appointment to a closer location that I could get to. There was no valid reason to ask me to travel to a busy business district in the morning when there are numerous doctors in my immediate area who could do the job.

After years of complying with the unreasonable demands, harassments and threats from Social Security, I recently received a letter dated December 24 stating that my assessment was done and that I’d continue to receive benefits. This is a huge relief! Now I feel as though I have my life back, and I can deal with the multiple health problems I face, I can get back to writing, and I don’t have to live in terror.

But what happens to those who can’t meet all of the governmental requirements? The disability attorney I spoke to said they couldn’t represent a person who might lose their benefits. Attorneys are paid through collecting a portion of the retroactive payment of new applicants. With the client merely keeping what they’ve got, there is no mechanism for the attorney to get paid.

The rigorous evaluation process, coupled with the lack of accessible representation for people with disabilities, means that many could be facing dire, life-threatening circumstances. I don’t want to think about it.

Jack Bragen currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.