Street Spirit Interview by Terry Messman

Street Spirit: You have been deeply involved in supporting military veterans, but there’s a saying that no good deed goes unpunished. Did Bill O’Reilly of Fox News actually compare you to Fidel Castro because you organized a Veteran’s Day event in 2005 that involved the Gold Star Families for Peace?

Country Joe McDonald: Yeah, he did that! He did say that! He said on his show that me doing a Veteran’s Day event in Berkeley was like having Fidel Castro in charge of it, after we got publicity because we wanted to have a Gold Star father speak in one of our Veteran’s Day events.

Actually, the local Disabled American Veterans group pulled out of it because the rumor was that the Gold Star families against the war were associated with Cindy Sheehan. It got back to Bill O’Reilly that Cindy Sheehan was going to speak at our event. On his program, he said that having Country Joe be in charge of a veteran’s day event was like having Fidel Castro be in charge of a veteran’s event. He compared me to Fidel Castro! This happened on the O’Reilly Factor on October 19, 2005.

So all that happened and then a couple years passed, but I never forgot that. And I was playing as part of a package ‘60s show called Hippiefest, and we played in New York City in July of 2007 in an amphitheater with about 15,000 people there, and it was a bunch of 1960s groups in concert. I had my own spot on that show and the rumor came that Bill O’Reilly was in the audience. I looked out and he was sitting in the second row, right in front of the stage.

Spirit: The arch-conservative Bill O’Reilly actually came to Hippiefest?

McDonald: Yes, at Hippiefest! He came to Hippiefest! So when it was time for me to go on to do my part of the show, I came out and told the audience that Bill O’Reilly had dissed me on his show by comparing me to Fidel Castro. I also mentioned that I was in the Navy and had been honorably discharged while he had never served, as far as I was aware.

I said to the audience that day that Bill O’Reilly and I are both in entertainment and it’s all fun and games, and I’d just like to dedicate the Fuck Cheer tonight to Bill O’Reilly.

Spirit: Was that a way of getting all the concert-goers to say, “Fuck Bill O’Reilly?” [prolonged laughter]

McDonald: Yeah, everybody really did the Fuck Cheer that night! I was standing on stage thinking, “Oh my God!” [laughs]

Then, after seeing the Hippiefest show, Bill O’Reilly went on and did his regular show, and he mentioned that he had gone to Hippiefest and that it was a pretty good show. And he never mentioned me or the cheer we did on his show ever since.

Spirit: I wouldn’t have ever again mentioned you or the cheer either! [both laughing]

When did you first become aware of Cindy Sheehan and the Gold Star Families for Peace and their protests against the Iraq War?

McDonald: I’ve been involved with the Unitarian Fellowship here in Berkeley at Cedar and Bonita for a long time, and I’ve done some things with them. And I was there when Cindy Sheehan spoke out for the very first time. They had three Gold Star parents there for one of the services, talking about their children who were killed as soldiers in the Iraq War.

At the end of the service, they passed the microphone around, and Cindy Sheehan spoke. She was there with her husband, and it was the very first time she had ever spoken in public. I got to know Cindy and her husband, and I watched with interest the progression of what politics and the death of her son in the Iraq War did to the family. They were a pretty middle-of-the-road family, and then Cindy became a left-wing notable. And then the family fell apart.

My mother was a political figure, obsessed with politics, and Cindy became obsessed with politics, and her husband was a really nice guy. And I sympathized with the whole family, and it was an interesting phenomenon about how history can sweep you up and do things to your family and your personal life.

It was also interesting to me that this important Unitarian Fellowship, this little congregation in Berkeley, could once again be a vehicle for launching a person and an issue into the national spotlight, because she went on to George W. Bush’s trail in Texas in protests over the Iraq War. It intersected with my life in several ways.

Suffering of Soldiers, Sorrow of Children

Spirit: Many of your songs describe the suffering of both the civilians trapped in war and the soldiers forced to fight. “An Untitled Protest” from the Together album is a meditation on the suffering of children and civilians in bombing raids.

McDonald: Yes, that’s what that song is about, the suffering of people who were the recipients of the U.S. bombs that fell down from the sky. It’s very poetic, that song.

I was at the church service in Berkeley when Cindy Sheehan, for the very first time, came out with two other Gold Star Families for Peace to discuss their sons being killed in the Iraq War. I sang that song, “An Untitled Protest,” about the destruction caused by war. They remarked about how hopeless it is that this destruction is taking place in a war zone, but you’re only sending cards and letters.

Spirit: In “An Untitled Protest,” people send letters to soldiers, while those very soldiers are running the “death machine” that rains down bombs on the children. It’s very moving.

McDonald: And it was very poignant for me to actually meet a mother and father who had sent cards and letters to their son who died fighting the Iraq War — which most people consider a war that never should have happened.

It’s the contradiction between what can you do about it and what’s really happening at the same time in the war zone. The song is not only about the soldier-children and their suffering in fighting the war, but also the children who are being killed in the war. And the hopelessness and impotent feelings of only sending cards and letters and giving medals.

What more can we do? We’re still struggling as a species about how we can stop war. What can we really do? You can get a feeling of hopelessness.

Berkeley’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial

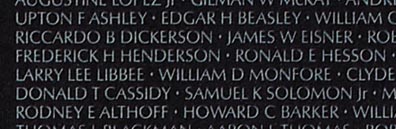

Spirit: What led you to keep urging city officials for so many years to establish a Vietnam Veterans memorial in Berkeley?

McDonald: Well, I got to know Jan Scruggs, the man responsible for helping build the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. Amongst ourselves, we began thinking about the cost of physical memorials and whether it was worth spending the money or not.

Spirit: You were wondering whether the money should be spent on memorials as opposed to services for veterans?

McDonald: Yes, that’s right. And I thought memorials were important for a healing thing, but I got the idea that you could have an electronic memorial and it wouldn’t cost very much to set up.

I raised some money from benefit concerts in 1990 to build a memorial in Berkeley for the 21 Berkeleyans who died in the Vietnam War. I wondered if we could build an interactive computer memorial where people could enter memorial comments about their loved ones who had died in the war. We created an Alameda Country War Memorial in 1991 and I kept thinking that we should have something similar happening in Berkeley.

Spirit: Berkeley was such a major center of the anti-war movement that it was surprising to see the city honoring the soldiers who fought in Vietnam. It was even more surprising for some to realize it was catalyzed by Joe McDonald, one of the anti-war voices of the sixties.

McDonald: It happened quite magically. I thought it would never happen, but Dona Spring, the City Council person who had the Berkeley Veterans Memorial Building in her district, stepped forward to sponsor it. The really incredible thing was that this 1995 memorial was the world’s first interactive war memorial. There had never been anything like that before.

The IT guy, Chris Mead, at the Berkeley City’s home page, said that he could build the Berkeley memorial for me with the 22 names, and that’s the memorial that you visited. This is the twentieth anniversary of that memorial.

I knew Jan Scruggs and he knew that I was doing this in Berkeley and then they went interactive also.

Spirit: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., saw the Berkeley model and they also went interactive?

McDonald: Yes, they went interactive. But Berkeley was the first city ever to have an interactive war memorial. People who are disabled and people who have all kinds of restrictions in their lives can’t visit a physical memorial. And a physical memorial requires maintenance and it’s very expensive to build these monuments.

So that’s how it all happened. It was like magic.

Spirit: The New York Times gave very positive coverage to the Berkeley memorial. But they also had a field day with the seeming contradiction that one of the radical anti-war voices in the best-known anti-war city was sponsoring a memorial to honor Vietnam veterans.

McDonald: Yeah, people have a hard time putting all the things together. Lots of people still don’t think of me as a military veteran. But it all makes perfect sense.

Spirit: How does it make sense that one of the most anti-war cities in the nation was honoring veterans of the war that it protested for so many years?

McDonald: Because we are part of America. We have people who joined the military or were drafted and who fought in the war. I mean, we didn’t secede from the union. We’re part of America.

When I did this memorial, I met families and they talked about how horrible it was for them to be grieving for their loved ones who died in the Vietnam War, and seeing people running around Berkeley waving the North Vietnamese flag, and there was no outlet for them.

So when we had our event on Veterans Day in 1995, it was the first time that some of these families had ever had any recognition for their sacrifice or any vehicle to express their feelings. I felt that not only was it important to hear from the people who fought the war, but also to hear from their families.

Terrible Price Paid by Families

Spirit: What is the most important thing you’ve learned in talking with families of the veterans?

McDonald: If you think that you can survive this sacrifice and this trauma in your family, maybe you’re wrong.

Spirit: Are you saying that some families don’t survive this loss on some level?

McDonald: How many parents and grandparents have drunk themselves to death or committed suicide because they lost their favorite son or daughter in a war? Whether the war is right or it’s wrong, whether it’s righteous or not.

Spirit: Yes. For many people, sorrow that deep never really goes away.

McDonald: It really is meaningless to say to somebody, “Thank you for your service.” It wouldn’t even help to take somebody whose son died in the war, and give them a brand new car in thanks. What do you really get? You get a flag. You get a free burial in a military cemetery. You really get nothing.

People don’t think of military families — the wives and husbands of people who are killed in the war. When the person is alive, their wife or husband gets to go to the PX and gets to live on the military base, and you get these perks. But after they’re dead, they don’t get even get that anymore.

Spirit: Bruce Cockburn wrote a song against war that says, “For every scar on a wall, there’s a hole in someone’s heart, where a loved one’s memory lives.” For every one killed in war, the same bullet also strikes a family member who loved them.

McDonald: And it’s more than one. There are countless people hurt. It’s hard to think about.

Spirit: Like the web page in the Vietnam memorial about the death of Berkeley resident Otis Darden in the Vietnam War. His relatives wrote so many beautiful memories about him.

McDonald: That’s right. It’s unbelievable, the Darden family. I can’t read that stuff without crying. It’s really amazing. And the love I got from those people. It was incredible. And it’s tragic.

I met the Darden family, and they were just so glad that somebody had finally done something. They were able to tell their kids that you can go to the display case in the Memorial Building and you can see this about your uncle or whoever it is.

I did get to know some of the families, and I was amazed at the love and respect that they gave me. They were so grateful that anybody would acknowledge their sacrifice. And I don’t mean sacrifice in a clichéd way. The war had reached out and struck their family in a horrible, terrible way. And possibly because it was Berkeley, they got nothing from their neighbors and friends. They retreated and were isolated among themselves. The mayor didn’t come to their house to thank them. Instead, there were demonstrations.

Spirit: So even though they had lost a son in war, it was never honored.

McDonald: That’s right. But not just honored — it wasn’t even acknowledged. It wasn’t acknowledged! And the lesson for me always is that history can suck you up and just spit you out. And you don’t know. You think you’re doing the right thing. A lot of people in the anti-war movement thought they were doing the right thing and they got many years in prison, and didn’t get support.

So life is precarious and dangerous and we need to respect EVERYBODY. We need to be inclusive, not exclusive.

Spirit: When you say that we need to be inclusive of the people who fought the war and their families, that seems to me like an essential part of nonviolence. It is saying that everybody’s life has meaning and value.

McDonald: That’s right. That’s absolutely right. And it has to be that way! It has to be that way! Who is better than anyone else? We’re just washed in blood. And we don’t even know why we’re here or where we’re going. We don’t know what the hell is going on. And we just have to be inclusive.

So that’s what I did with the memorial, and it was a miracle that it happened.

A neighbor’s son dies in Vietnam

Spirit: Is it true that one day when you were talking with one of your neighbors in Berkeley about how veterans are treated, you unexpectedly found out that his own son had died in Vietnam?

McDonald: Yes, the Henderson boy, Frederick Howard Henderson. He was named after his father. And that was one of the things that just spurred me on. He lived right across the street from me and he was taking care of a neighbor’s garden one day, and he asked me, “What have you been doing lately?”

So I told him I got all involved in being a veteran and talking about the Vietnam War. He said, “Oh, my son died in the Vietnam War.”

And I said, “Oh, my God! I didn’t know that!” His son’s name somehow got left off the California State Vietnam War Memorial in Sacramento, because it was a bureaucratic mistake.

[Editor: Frederick Howard Henderson was a Berkeley resident, but since he had attended West Point, he was listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in D.C. as a New York resident since that was his last address before he died in Vietnam on November 3, 1966. When I searched for his name on the Vietnam Memorial, it was stunning to find an entire page that listed 48 Hendersons who died in Vietnam. See the photo of his name on the wall.]

Spirit: What impact did that have on you to learn that your neighbor’s own son had died in the war?

McDonald: It just personalized it for me. I went to Washington, D.C., and I made a rubbing of his name on the wall of the memorial and I brought it back home to his family, and I gave it to them. It meant to them that someone had acknowledged their loss — and that made it more human. It personalized it, and it made it real because this all becomes so abstract.

We’re surrounded by people who have lost family members in war, and we need to talk about it. I was shocked by it, and it affected me deeply, and spurred me on to do these things to remember veterans.

So we built this electronic memorial. Then, after 1995, somebody raised money to put a bronze plaque on the Berkeley Memorial Building with the 22 names of Berkeleyans who died in the war.

Then I thought that San Francisco should have a bronze plaque, and I got Swords to Plowshares, a veterans advocacy group in San Francisco, and the San Francisco mayor to build a bronze plaque for the 134 San Franciscans who died in the Vietnam War. We installed it in Justin Herman Plaza. We’re in the process of moving it to the newly refurbished San Francisco War Memorial.

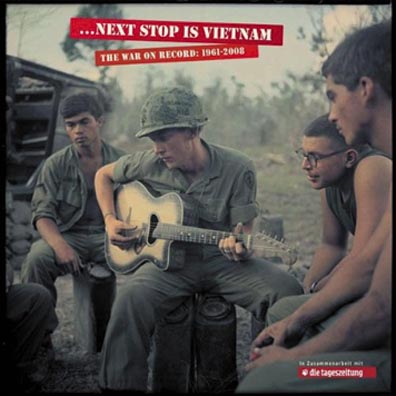

Next Stop Is Vietnam: The Bear Family Box Set

Spirit: You found a new way to lift up the voices of Vietnam veterans by compiling two CDs of their songs for the Bear Family box set, Next Stop is Vietnam: The War on Record. Even the title of this massive collection of music quotes your song, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die.” How did you find so many songs by Vietnam veterans for this anthology?

McDonald: Well, I met the veterans in my travels, when somebody said, “You’re a veteran too.” I started going to all these veterans’ events. When I traveled around, I would meet people and they would give me their own tapes and CDs of the music they had made. I just collected them. Some of those guys I knew personally and some I just met.

When they were building the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., I was in D.C. and I saw the foundation of the memorial that Maya Lin designed. So we all started thinking about memorializing the Vietnam experiences, and one thing led to another. One of the guys who put together this box set has an enormous collection of 2,000 or 3,000 songs about Vietnam. His name is Hugo Keesing. And in the end I sent him what I had.

Spirit: Why did Bear Family Records become interested in releasing such an enormous collection of 13 CDs of songs from the Vietnam era?

McDonald: I simply emailed Richard Weize (founder of Bear Family Records) and said that he should put out a box set of the music of Vietnam veterans because there is an important body of work there.

Then he contacted two scholars, one a professor and one a veteran who had collected music, and they started compiling this box set. He said it is the biggest box set he had ever done.

Spirit: That’s really saying something, because Bear Family is known for releasing the largest and most comprehensive box sets of country, blues, rock, and other kinds of music.

McDonald: Right, and that’s the reason I contacted him, because they had done a box set of music of the left wing — the music that I grew up with by all those Pete Seeger-type people. I got that box set and I listened to it and I recognized a lot of the music I had heard as a child on 78 records.

[Editor: Bear Family had released a 10-CD box set of leftist, progressive, urban folk music: “Songs for Political Action: Folk Music, Topical Songs and the American Left.”]

So I knew that he did box sets and that he was interested in music about sociopolitical issues, even though 95 percent of what they do is just popular music, so I thought that maybe he would do a box set on Vietnam-era songs. And I was quite surprised that he did do that.

They began putting the box set together and they sent me this list of 11 CDs of songs from the Vietnam era, with all of this stuff that I didn’t know about, including all kinds of country-western, pro-war songs, with notations about every single song. But there were hardly any anti-war songs. So I said, “What the hell, Richard! You don’t even have the stuff I told you to get in the first place — the music of the Vietnam veterans.”

So he said, “Wow. OK, I’ve never done a 13-CD box, but I’ll see if we can figure out how to put the other two CDs in.” Those are the two CDs that I had insisted that he do. So they put together the last two CDs with the point of view of the Vietnam veterans themselves. A couple of my songs are included on the set. (“I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” and “The Agent Orange Song.”)

Spirit: Didn’t they also ask you to write the forward to the hardcover 300-page book that Bear Family released with the box set?

McDonald: Yes, I wrote the forward and I tried to explain in the forward how important it was to hear from the Vietnam veterans. Because that is what started me on these songs from Vietnam veterans, was understanding you should hear from these people who have had the experience themselves if you want to know about it. That’s the most powerful thing.

The majority of the songs in this box set are not from veterans. They’re from singer-songwriters — commercial songwriters who were attempting to write songs that they thought would be popular and sell records, like any new fad in popular music.

Spirit: So you gave veterans a voice of their own in this box set, a voice they would not have had except through your advocacy?

McDonald: I gave them a voice by doing this. The interesting thing is that the songs by the veterans were produced by themselves. Almost none of the other commercial music was produced by the artists themselves.

Spirit: The veterans didn’t just perform these songs, but actually produced and recorded them on their own?

McDonald: Yes, because it’s an era in which you can make your own recordings. Often the veterans went into recording studios, or they recorded at home, and made their own CDs.

Spirit: So it’s the genuine voice of veterans exactly as they wanted their songs to be heard?

McDonald: That’s right. And I listened to all of the box set. I wound up listening to the whole thing and it took me 10 or 12 hours, and I read all the text, too. It was quite amazing and quite interesting.

Spirit: What do you think it means to have the music of the Vietnam era documented in this way?

McDonald: I felt it was important to document this music in hard copy because history is written by people going to books and stuff like this. So it exists in one spot, one place now. It exists — the history of the songs of the Vietnam War and the voice of the Vietnam veterans themselves. Before it was all just floating around undocumented.

Songs of Nature and Ecology

Spirit: People often think of you as a songwriter on all the issues surrounding war and peace. What led you to compose songs about saving the whales and to become involved with ecological issues?

McDonald: In 1975, I read a book by Canadian writer Farley Mowat titled A Whale For The Killing. In the book is a description of a whale. I was shocked to realize that I did not understand what a whale was. This book led to my writing the song, “Save The Whales.”

Next, I read Mowat’s book about wolves, Never Cry Wolf. Really, one thing led to another and I began to take a break from songs about war and soldiers and get into animals. I learned about condors, coyotes, seals, whales, and wrote songs about them and began to think of ecology. After all, war is not only a problem for humans but also for animals and the environment.

The mid-1970s were a time of great change in this area. The Save The Whale movement took off all over the world and with it, education about animals and human interaction with them and global ecology.

Spirit: It’s interesting to see what a major impact that just this one book had on your awareness of environmental issues — and through your songs, it affected many other people as well.

McDonald: After reading Farley Mowat’s book, I wrote the song “Save The Whales” and put it on my 1975 album Paradise With An Ocean View. I got two graphic ideas for that album. One was to include a poster of a mother and baby whale and to picture on the cover a bulldozer knocking down nature.

At the same time, I got a request to participate in Vancouver, British Columbia, in an event sponsored by Greenpeace. We sent them lots of the posters and they used them to publicize their event. A big part of the Greenpeace event was the ship Rainbow Warrior taking off from Vancouver to go into the ocean to stop nuclear bomb testing in the ocean and also efforts to save the whales. I met the captain of the Rainbow Warrior and the crew. That was the ship that soon after was blown up in New Zealand by the French Secret Service, resulting in one death.

Soon after, I participated with Crosby Stills and Nash at a benefit for Cousteau Society and met Jacques Cousteau. This got me interested in the annual baby seal kill for their pelts. I wrote the song “Blood On The Ice” and put it on my next album Goodbye Blues.

During a tour of England, I met an animal rights group and we got the idea to make a benefit album for them called Animal Tracks that featured all of my animal and ecology songs. The record had songs about condors, coyotes, whales, native people being kicked off their land, auto pollution, nuclear power plants, and anti-hunting songs. The song “Global Affair” was about ecology.

I also participated in a very large protest in Trafalgar Square in London, protesting the baby seal hunt. And I got interested in coyotes. My father, who grew up in Oklahoma on a farm and was a cowboy, introduced me early on to Ernest Thompson Seton’s book Wild Animals I Have Known. I read his book and other books on coyotes. I found out how the government was killing coyotes to protect the cattle and sheep industry.

Spirit: It’s like a declaration of war on the animals, and all for the sake of profit.

McDonald: My concept of peace on earth began to change to include all living things. I began to see a similarity between the way we demonize the enemy in war and the way we demonize animals to justify killing them. And the way we think of animals — and for that matter, nature — as not feeling or being sentient beings with a right to live, so it is easy to kill them.

Slowly, these new thoughts began to merge into a concept of ecology. I wrote some songs about nuclear power plants and how radiation can not only kill us but kill all living things.

Spirit: Even back in your Vietnam songs, you were already writing about ecological concerns and the environmental damage caused by Agent Orange. Very few songwriters have ever written so extensively about the issues of war and peace, let alone so many songs about social justice and ecology.

McDonald: These are very large concepts and difficult to imagine and articulate. As a songwriter, it is hard not to be writing propaganda. It is very hard to be entertaining and inclusive with this subject matter and tell the truth. But I find it challenging and fun.

There certainly is a limit to what an audience will enjoy and think about. If you give too much information, they lose interest or just become upset and overloaded with the information and feel guilty. I heard that Woody Guthrie said he wanted “to be someone who told you something you already knew.” I like that.

My album Peace On Earth had a cover art of a peace sign overlaid on top of a drawing of Planet Earth. It featured two songs about peace, “Peace on Earth” and “Live in Peace,” that summed up how I now feel about war and peace.

Joe Joins the Navy

Spirit: You’re one of the very few anti-war rock musicians of the Vietnam era that was a military veteran first. Why did you enlist in the Navy in the first place?

McDonald: I wanted to travel, get out of my home town, and have sex. [laughs]

Spirit: You only enlisted to travel and have adventures? I’m shocked.

McDonald: You would be surprised how many people join the military for those reasons. The main reason that I joined the Navy was that the recruiter told me I could fly a jet plane — which was a complete lie. And that’s something that often happens. So I joined when I was 17. I had to have my mother sign a piece of paper to let me do it because I wasn’t 18.

Spirit: Where did you go to boot camp and where were you then stationed?

McDonald: I went to boot camp in San Diego. I almost never graduated from boot camp because I couldn’t learn how to tie all those knots they do in the Navy. I joined the drum and bugle corps in boot camp.

One reason that I joined the Navy was I saw a picture of a guy holding flags on an aircraft carrier. I didn’t know what that job description was. But I took some tests and then they asked me in an interview what I would like to do.

I said, “I’d like to hold those flags.” The guy said, “Oh, you mean air traffic control?” And I said, “Yeah, I guess so.”

So they sent me to Olathe, Kansas, to the air traffic control school. After one month, I said to the instructor, “When do we get to learn this thing about the flags?” He said, “That’s the signaling school. You’re in the wrong school!” But it didn’t matter by then because it was too late.

Then they sent me to Japan and I was stationed at the Atsugi base in Japan where they stationed the U2 spy planes. I worked in flight operations, passing flight plans back and forth and giving pilots their maps. Then for a few months I was at a little gunnery range up in the country in Japan where people trained to keep current and maintain combat status in the various kinds of aircraft gunnery.

Spirit: How did your left-wing parents feel about you going into the military?

McDonald: My mother didn’t seem to mind. My father was shocked that I did it, but she signed on. We never had an argument or anything. Years later, though, she didn’t understand my sympathy towards Vietnam veterans. That’s what she didn’t understand.

Spirit: You’ve said that she didn’t understand because she thought soldiers were responsible for war crimes.

McDonald: Well, she was Jewish and she knew about the Holocaust. So to her, a soldier was a soldier, and she thought they were baby killers, like everybody else thought at the time, and she did not understand. But she came to believe in the end — along with the other liberals — that the veterans got a raw deal from the government.

Jane Fonda and Free The Army

Spirit: On your Vietnam Experience album, the song “Kiss My Ass” tells the story of a blue-collar kid shipped to Vietnam who can’t stand the way the military pushes him around. Why did you write that song?

McDonald: I wrote it for Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Absolutely.

Spirit: So you were trying to give a voice to soldiers on the front lines?

McDonald: Yeah, the Vietnam Vets Against the War loved it.

Spirit: It’s a great blast against the war. You sang “Kiss My Ass” when you were involved with Free the Army, the performance troupe that brought the anti-war message to GI coffeehouses. What was the FTA experience like for you?

McDonald: Well, it happened completely organically. My wife at the time, Robin Menken, was connected with The Second City and with The Committee, the agitprop theater group in San Francisco, and she got to know Jane Fonda. Jane Fonda got this idea to put together the Free The Army show, and they put together a show with Donald Sutherland, and decided to get me involved in the show, singing my “Kiss My Ass” song and “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die.”

I think I was the only military veteran involved in the show. We played at GI coffeehouses next to Army bases. A lot of those guys knew me already from my Vietnam Veterans Against the War activities. My then-wife Robin wrote some of the scripts. So I did about five shows with them at GI coffeehouses, including in Killeen, Texas, at the Oleo Strut. [Editor: In the late 1960s, GIs turned the Oleo Strut, a coffeehouse near Fort Hood in Killeen, into a major center for anti-war organizing.]

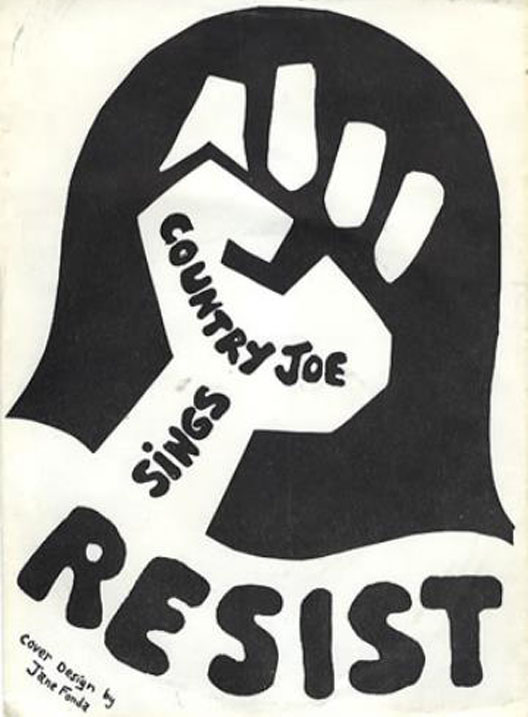

I made a third EP raising money for Jane Fonda’s Entertainment Industry for Peace and Justice, and the Resist EP included the songs “Kiss My Ass” and “Tricky Dicky” and “Free Some Day.” We sold it as a fundraiser for the anti-war GI shows. Jane Fonda helped to design the cover for the EP when she was sitting in my house.

Donald Sutherland was at all the shows, but Jane Fonda was the star power for Free The Army. She had just come from being an activist with Native Americans at Wounded Knee, and that sort of thing. She was very naïve about politics and never consulted me in any way about these GI issues.

We had done quite a few performances and I was disenchanted because they didn’t want me talking at the press conferences. I got the impression that she thought she knew what was best in talking about the GI movement. We were doing this skit, and I suggested that one of the women could act as Lyndon Johnson in the skit, and she said that the GIs were just working-class guys who didn’t know how to spell, so we couldn’t get too complicated. I got insulted by that because I was a working-class guy myself, so I left the show. And she went on to infamy.

I knew that she was being taken advantage of by the radical left wing. They were using her as a propaganda tool. I refused to go to the Philippines with them, and she hung up the phone on me. [laughs] She went on to the Philippines and on to North Vietnam and she was used by the North Vietnamese, and used by the radical left. It was really a shame because she meant well. But she was very naïve — and there you go. The radical left was looking for star power.

But I never liked the radical left because, like I said with my family, we never got anything from the radical left. I knew that they were pretty ruthless in the way that they would use people. And the North Vietnamese were ruthless in the way that they would use regular people. Politics is ruthless.

Street Spirit’s in-depth look at the music and the man: Country Joe McDonald

Country Joe: Singing Louder Than the Guns (April 2016)

Country Joe McDonald stands nearly alone among the musicians of the 1960s in staying true to his principles — still singing for peace, still denouncing the brutality of war.

Songs of Healing in a World at War (April 2016)

Country Joe McDonald’s songs denounce the atrocities of war and pay tribute to Vietnam War combat nurses and the legendary icon of mercy, Florence Nightingale, for bravely bringing medical care into war zones.

Carrying on the Spirit of Peace and Love (June 2016 Issue)

Country Joe McDonald has carried on the spirit of the 1960s by singing for peace and justice, speaking against war and environmental damage, and advocating fair treatment for military veterans and homeless people.

Street Spirit Interview with Country Joe McDonald Part 1 (April 2016)

Women coming home from the Vietnam War never were the same after their wartime experiences. They were shoved into a horrific, unbelievable experience. That’s what I wrote about in the song: “A vision of the wounded screams inside her brain, and the girl next door will never be the same.”

Street Spirit Interview with Country Joe McDonald Part 2 (April 2016)

“It was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, London, and San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. It was a wonderful thing to happen. And I’m still a hippie: peace and love!”

Interview with Country Joe McDonald, Part 3 (June 2016)

“We’re still struggling as a species with how we can stop war. The families (of Vietnam veterans) were so grateful that anybody would acknowledge their sacrifice. And I don’t mean sacrifice in a clichéd way. The war had reached out and struck their family in a horrible, terrible way.”

Interview with Country Joe McDonald, Part 4 (June 2016)

“I knew a lot of the people had to escape or they were killed by the junta in Chile. It was just tragic and terrible. I had grown up with a full knowledge of the viciousness of imperialism from my socialist parents. So I knew that, but I was still shocked.”