by Osha Neumann

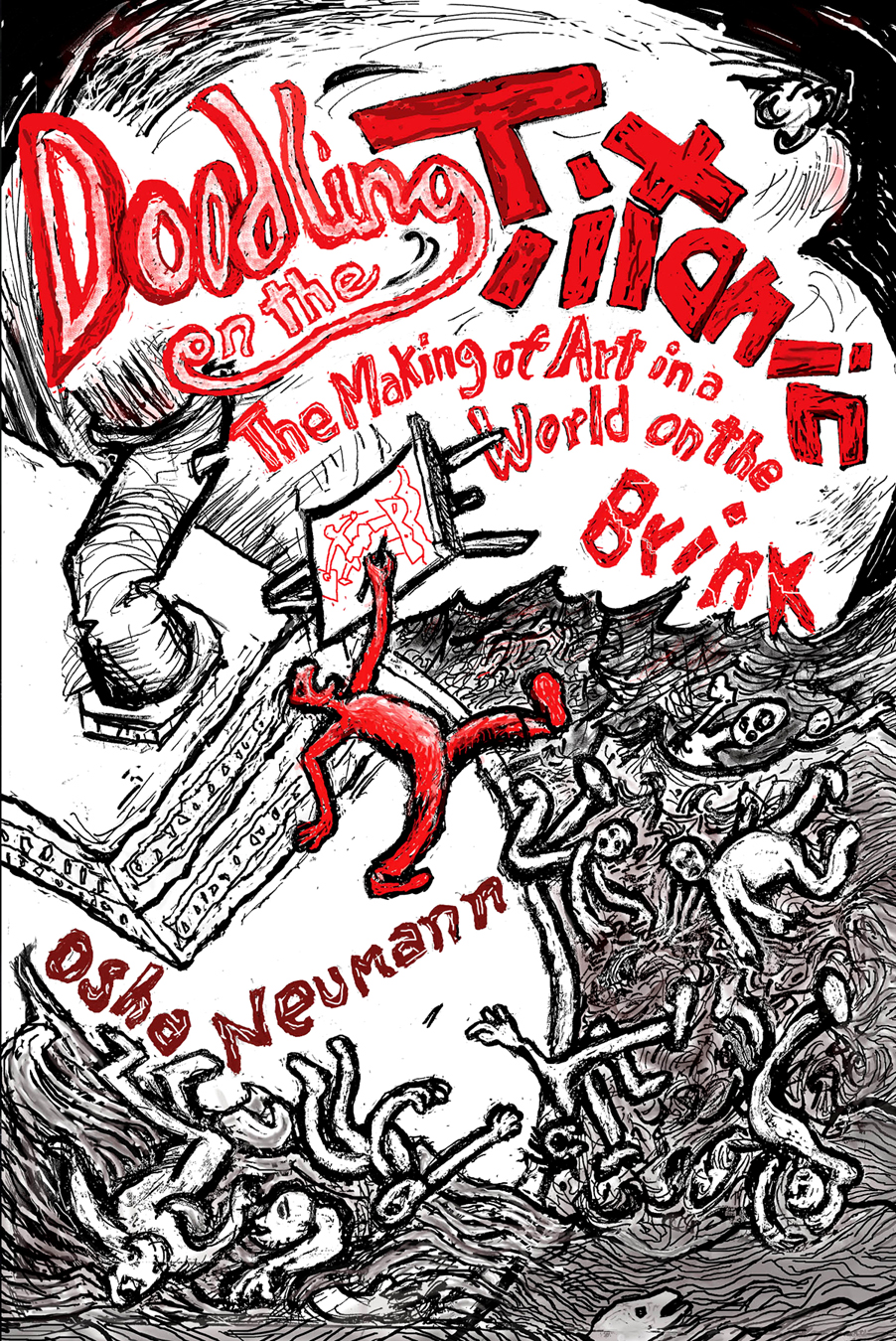

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]his very odd question occurred to me after Terry Messman, the editor of Street Spirit, suggested I write something for the paper in conjunction with the publication of my book, Doodling on the Titanic: the Making of Art in a World on the Brink.

My day job as a lawyer defending people who are homeless doesn’t give me much chance to think about beauty. I’m all about how to squeeze my clients through the loopholes of law and convince a judge that even though they sleep without a roof over their head, they’re still covered by the Constitution.

Beauty doesn’t enter into it.

But here I am, sitting in court, waiting for the judge to take the bench and this question—Are Homeless People Beautiful? — is roiling around in my mind.

I don’t argue in court about whether homeless people are beautiful. It’s not something on which a judge will render a verdict. Nevertheless, aesthetic judgments about people who are homeless are always there in the mix, disappearing into a crowd of judgments about their cleanliness, their criminality, and the risk they may or may not represent to society’s health, well-being and economic prosperity.

These judgments are there in the court in which I am now sitting. They are there in the court of public opinion.

And usually they are negative.

Are Homeless People Beautiful? The answer generally is no. They are not.

This should not be surprising. People who are homeless are the targets of prejudice. And the target de jour of prejudice is invariably stigmatized as bad and ugly, morally and aesthetically displeasing.

“Dirty Jew,” the anti-Semite shouts, “with your ugly hooked nose.”

Many Jews in Israel have much the same opinion about Palestinians.

Call to mind all the racist images of people whose skin color tends towards black. Now think of the public image of people who are homeless: dirty, smelly, unkempt, lazy.

The targets of prejudice are invariably dirty. Dirt is a sign of moral degeneracy. It is unhealthy and it’s ugly. Like excrement. If it’s in the street, it needs to be cleaned up. Then the street will be beautiful again. Metaphors of cleansing abound where prejudice attempts to rid itself of those who offend it.

Homeless people are constantly cited for what we call “quality of life” offenses: blocking the sidewalk, trespassing on church steps, lodging (whatever that means), remaining in the park after curfew, etc. etc. I’m in court right now to defend my clients against just such charges.

But I can’t help feeling their underlying offense is that they violate society’s sense of order — order not just as in “law and order,” but an order that people perceive as attractive, comfortable, and ultimately beautiful.

The good, the true, and the beautiful are the triumvirate at whose feet we worship. The bad, the false, the ugly, are their opposite. How did homeless people end up on the wrong side of that great divide?

Women are tyrannized by concepts of beauty. They mutilate themselves with liposuction and Botox, and strenuous dieting to conform to an impossible ideal.

Homeless people are also tyrannized by a concept of beauty to which they will never be able to conform as long as they remain homeless.

I like to think of beauty as something everyone on the planet can appreciate. We all find sunsets and meadowlarks and fields of blooming flowers beautiful, whether we are rich or poor, housed or homeless.

Beauty is liberating. A joy. A relief from toils and troubles.

So how did it become a cudgel with which to beat people up?

The judge is late. Court was supposed to begin ten minutes ago. I start to scribble my thoughts on a yellow pad. Then I’m stopped by a thought.

I’ve been thinking of what others think about people who are homeless. How would homeless people answer the question, “Are Homeless People Beautiful?”

My guess is they’d find the question ridiculous. Their answer might be something like: “Well, Joe here is a beautiful guy, but Gus over there—he’s ugly as sin.” Or, “Maureen keeps her campsite nice and clean, but Davida’s place is just a mess.”

Then I think, well maybe the answer of the homeless would not be that different from that of the housed. Almost all homeless people would prefer to have a home. If they could be miraculously transported to one of those mansions in the hills with glorious views of the Bay — all clean and tidy, tastefully furnished, freshly painted on the inside and landscaped on the outside — would they not find their new surroundings beautiful, and their old campsites, by comparison, not so much?

Poverty is ugly.

Homelessness is a blight on a society as rich as ours. Why pretend that homelessness is beautiful?

Perhaps the only difference in point of view between those who use the concept of beauty to beat up on people who are homeless, and those of us who use it as a beacon pointing the way toward a better world awaiting, is the conclusion we draw from our observations, and the direction to which our moral compass points.

Once people who are homeless are not seen simply as “the other,” but are seen as kin to us who are housed, then we housed ones will find in the houseless, the range of beauty, truth and goodness that resides in all of us. It just takes familiarity.

I really believe that. And I am comforted by this conclusion. It preserves my hope that all human beings can share in a common perception of the beautiful.

But it implies that universality can only be achieved if beauty can be extricated from all the moral judgments, contempt and disdain that infect it when it is applied to groups that we disparage. Perhaps inevitably, where we stand in the hierarchies of society — housed or houseless, rich or poor, comfortable or uncomfortable — will infect our judgments about the beautiful, and until those hierarchies are dismantled there will not be a universal concept of beauty that we can all share and which will not be a tyranny of one group over another.

Here’s a case study in divergent perceptions of beauty:

In Albany, California, just up the road from Berkeley, people who are homeless lived for many years on an overgrown landfill amidst the fennel, the coyote bush, and the pampas grass. All manner of birds flew overhead and nested in the pines and palms, the acacia and the bay laurel. Lizards, ground squirrels, mice and rats scurried through the underbrush and clambered over the rubble. Trails meandered to hidden campsites, dead-ended at cliffs and wound down to the waterfront where, for many years, my son-in-law and I made sculptures of the scrap wood and metal which the landfill supplied in abundance.

I loved the place. I found it beautiful. And I wasn’t alone. A whole host of us from all walks of life, especially including the folks who made the landfill their home, loved its wild unruliness. We loved its welcoming anarchy. We loved that there was still a piece of land on the edge of the city, untamed, un-pruned and unplanned.

The powers that be hated everything we loved. Where we saw beauty, they saw ugly. The landfill didn’t look the way a park is supposed to look. Bad things happened there. Drugs were consumed, dogs barked, sometimes angrily, and even bit people once in a while. Some of the campsites of the landfillians were unsightly piles of refuse and garbage.

At council meetings, the elected representatives of the citizens of Albany sat on the dais, rigid and uncomfortable, when we came to beg them to leave the landfill as it was. Representatives of the local Sierra Club chapter lobbied furiously to kick the homeless out, claiming to speak for nature, but in fact speaking only for their preferred version of nature. The council members listened to them, for the Sierra Club was a great power in Albany.

And so the homeless for whom the landfill was home had to go. The place needed to be cleaned up. Tamed. Made beautiful. The powers that be mobilized the forces they had at their command — first police and lawyers, then maintenance crews and garbage collectors. With the big stick of citations for violating Albany’s camping laws and the wilted carrot of a little cash for a few and empty promises of housing, they cleared the place out.

Now it sits empty, life-deprived, and sad, a shell ready to be bulldozed and wrestled into the form of a proper park.

The “stakeholders” in Albany detested what we saw as beautiful. We detest the prim, proper, tamed, shorn and shackled, unwelcoming and un-nurturing nature they admire.

Conclusions? I have only more questions.

In art, there is no such thing as ugly subject matter; there are only ugly paintings. There are beautiful paintings of the deformed and wretched, the broken and disabled, and there are ugly paintings of the muscular and symmetrical, the young, the toned and curvaceous. Is that observation even relevant?

Can we extricate our idea of beauty from moral judgments? Is that even something we should do?

Oops. No time for answers, even if I had them. Got to put my yellow pad away. The judge is taking the bench.

Selections from Doodling on the Titanic

by Osha Neumann

On the value of art when the going gets rough

A condemned prisoner in the hours before his execution might write a poem, and would no doubt appreciate the pen and paper with which to do it, but he would certainly prefer a file to saw through the bars or a gun to shoot his way out of jail.

On whether art takes sides when armies fight

The sound of bugles leads armies into battle, but the beauty of a song rises above the conflict, and the same melody, with the words changed, can inspire either side. The truly great works of art, no matter how fervently they were painted against their times, no matter the scandal they once provoked, eventually are accepted into the fold, and take their place, like honored elders, in the hushed galleries of the museums of the world.

On the relation of art to revolution

The revolutionary on the barricade fights to return the world to the people. She raises her fist and shouts: “You stole our lives, our health, our happiness. You stole the wealth wrung from the earth by our sweat and blood. The diamonds dug from your mines belong to us who work in their dark bowels. The wheat in your sunny fields belongs to us who planted it and reaped the harvest. You have sold the fruit of our labor and pocketed the profits. We want what’s ours. We’ve come to take the world back.” The artist also struggles to take back the world. Van Gogh struggles with the sunlight and the wheat to make it his, to appropriate it. He struggles alone, but if he succeeds, his victory belongs to all of us. His struggle is not with the bosses or the owners of the wheat field. The police will not be called when he leaves with his picture under his arm. He takes only the image, not the reality, only the hope, not its realization.

On the making of art in a world on the brink

Art has always been the hope of the hopeless, the refuge of those without shelter, the joy of the bitterly sorrowful. Without hope, there can be no art; and without art, there can be no hope. When all hope is lost, we seek solace in a song. The mother whose child is dying in her arms will, in its last moments, croon a lullaby to sooth it toward sleep. And if we, as humanity, are killing our mother, we might as well croon a lullaby to ourselves, and rock ourselves in each other’s arms, as we descend into the everlasting sleep of the human race.

******************

Doodling on the Titanic is available online from Amazon (if you can stand it) and Barnes and Nobles. It can be ordered by your local bookstore. Osha Neumann can be contacted at oshaneumann@gmail.com

Book Launch Party for Doodling on the Titanic

January 22, 7 p.m.

Middle East Children’s Alliance (MECA)

1101 8th Street (near Harrison) in Berkeley