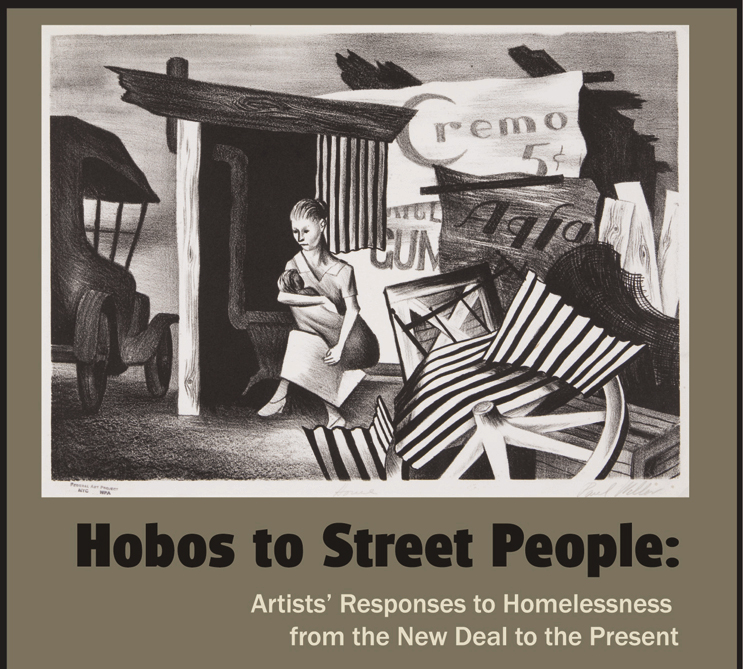

Hobos to Street People: Artists’ Responses to Homelessness from the New Deal to the Present

by Art Hazelwood

Published by Freedom Voices, 2011

Review by Margot Pepper

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he last thing one would expect an art show and catalogue focusing on poverty to do is inspire, particularly during such challenging economic times. Curator, artist and author Art Hazelwood has masterfully juxtaposed art created during the Great Depression of the 1930s to the daring perspectives of artists interpreting similar themes today.

Hobos to Street People: Artists’ Responses to Homelessness from the New Deal to the Present is empowering because it validates our experience of an America denied us by mainstream media.

Laws have been won, and agreements signed to ensure that the widespread levels of poverty of the Great Depression won’t reappear. But these laws and agreements have slowly eroded, resulting in the most massive increases in homelessness, hunger and misery since the 1930s.

The federal government has decimated federally subsidized housing and terminated Aid to Families with Dependent Children, the lifeline welfare programs launched under the New Deal to lift poor families out of abject poverty. In destroying these programs, the U.S. government has broken the promise it made at the height of the Depression that poor families would not be allowed to sink below a certain level of economic misery.

The hope conveyed by the Hobos to Street People exhibit comes from the artist as historian, as a witness to these broken promises, like the heartbreaking photographs by Robert Terrell, whose ironic title — “Everyone Has the Right to…” — draws attention to the failure of the United States to live up to its obligations under the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, drafted by a committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt.

The Universal Declaration states: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.” (Article 25, Section1, 1948.)

At times, it’s difficult to discern which images in Hobos to Street People were born of the Great Depression and which were taken today. Were it not for labor writer and photo essayist David Bacon’s use of color in his photographs, we might believe his subjects were contemporaries of those in the black-and-white stills of migrant workers taken by Dorothea Lange during the Dust Bowl.

In Art Hazelwood’s linocut, “The Four Freedoms,” the opposite is true. Here, the medium is reminiscent of the style of Leopoldo Menendez, a collective member of Mexico’s 1940s Taller Gráfica. It is the all-too-familiar glimpse of the skeletons in our country’s closet that gives away the piece’s time period.

The title of Hazelwood’s artwork harkens back to a famous series of paintings by Norman Rockwell referring to a 1941 speech in which President Roosevelt outlined the “four essential human freedoms.” In a satirical twist, Hazelwood depicts “freedom of assembly” as a line outside a present-day homeless shelter, reminiscent of the bread lines so prevalent during the Great Depression.

Hazelwood’s black-humor interpretation of “Freedom from Fear” for poor communities is a homicide victim whose death has liberated him from fear of gangs and police brutality. The thug-like depiction of the policeman outside a home evokes images of deadly home invasions that have brutalized poor families of color and disquieted activist communities by seizing personal computers and files.

Contrary to the stereotype of returning soldiers coming home to parades and buxom babes, Sandow Birk’s “GI Homecoming, 2008” shows the slum-like reality that awaits the majority of vets, many of whose dismal economic prospects have driven them to enlist in the military as a last recourse.

In “Faux Street Revisited,” Christine Hanlon provides us with the perspective of a homeless woman seated on a sidewalk, lost in a sea of disembodied legs, ignored and shunned by those who pass by in uncaring haste, leaving her in desolate loneliness in the midst of a crowd.

But not all subjects in the show are victims. It could be said that resistance is epitomized by the strength of the Dust Bowl woman who has her back against the wall in Richard Correll’s “Drought,” or the unyielding “Dustbowl Farmer” in Dorothea Lange’s Depression-era photograph.

Modern interpretations of resistance are more satirical, like Doug Minkler’s explicit poster that happily answers the artist’s rhetorical question: “Who Drives the Cycle of Poverty? (A. Welfare Queens, B. Illegal Aliens, C. Bleeding Heart Liberals. D. Capitalist Pigs.)”

Jesus Barraza, of the mostly anonymous, militant San Francisco Print Collective, challenges the viewer with his 2001 poster which asks: “How Many People Do You Need to Start a Revolution? There are 15,000 Homeless People in San Francisco. Is that Enough?”

In “Holiday Home,” Jos Sances paints an inviting, snow-covered home reminiscent of a Hallmark Christmas card, then spotlights the shopping cart of the homeless passerby. But Sances doesn’t stop there. The interactive work provides Advent Calendar-style windows that can be opened to reveal shocking images that have led to the piece being banned at a few venues.

In the accompanying book that catalogues the exhibit, Hobos to Street People (Freedom Voices, 2011), Hazelwood’s clear history joining the two periods sheds light and hope on our own times. Workers have had their backs against the wall before and they have fought back and moved the scrimmage line forward quite a bit to gain many of these rights.

Unlike Obama’s administration, Roosevelt was responding to avert rebellion — general strikes and collective self-help actions by the unemployed, unions and tenants facing evictions.

The Depression-era working class was far more organized than at present, either through unions or self-help groups who were intent on helping themselves without government support, like the unemployed miners in Pennsylvania. Teams of miners illegally dug and mined coal on company property and sold it themselves below the company’s commercial rate. Local juries refused to convict them and jailers refused to imprison them.

In A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn wrote that FDR’s reforms “had to meet two pressing needs: to reorganize capitalism in such a way to overcome the crisis and stabilize the system; also, to head off the alarming growth of spontaneous rebellion in the early years of the Roosevelt administration….”

The goal was to stabilize the economy and to keep the lower classes “from turning a rebellion into a real revolution.”

It was a time when the working class began to identify with the previously vagabond or destitute; a time when the Depression-era artists in this show united, not with the ivory towers of the elite, but with the displaced working class to which they actually belonged.

But red-baiting flared up as blowback to the worker-centered organizing of the 1930s and 1940s, followed by rampant McCarthyism, under which hundreds of socially conscious artists, educators, union members and government employees became the subject of aggressive investigations and questioning.

Those issued subpoenas to appear before government panels were required to name alleged communist sympathizers or end up on a “do not hire” list depriving them of their livelihoods. Sadly, the repercussions of the Blacklist continues to silence political art, film and literature to this day, redefining art with social commentary as crude or mediocre. The modern-day artists featured in Hobos to Street People are a bold example of those who have remained true to their visions in spite of attempts to marginalize them.

In addition to the Blacklist, the post-war boom had the effect of enticing more affluent artists to refocus on problems of aesthetics instead of those plaguing their own class. The emergent middle class was housed at the expense of the poor, fragmenting the alliances that had formed during Roosevelt’s time.

More than half a century later, the campaign to stigmatize and divide the formerly working poor from the active working class has succeeded. The public seldom blinks when the media scapegoat and deride homeless persons.

Hobos to Street People undermines the mass media’s effort to demonize the poor by making it impossible to see those of us whose options have been reduced to belongings in a shopping cart through the same old dehumanizing lens.

It unites the viewer with workers of past generations who overcame unjust economic conditions. It reunites us with our dispossessed counterparts by reminding us of our own historic political vulnerabilities and losses — but also, what justly belongs to all citizens of civilized societies.

Building this unity is the first step toward the genuine change falsely promised by a regime that talked New Deal, but has only delivered — to those of us who do not have corporate personhood — a Rotten Deal.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

‘Hobos to Street People’

Book Release Party and Art Exhibition

Freedom Voices will donate part of the proceeds from book sales to Street Spirit. To buy the book and also donate to Street Spirit, visit http://freedomvoices.org/new/hobos and enter Spirit in the coupon code/comments section of the online order form.

Book Release Party for ‘Hobos to Street People’

Thursday, Sept. 15, 2011, 5 to 8 p.m.

Alliance Graphics, 1101 8th Street, Berkeley, 94710

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

‘Hobos to Street People’ Traveling Exhibition

On view now through Dec. 4, 2011

The de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara University, 500 El Camino Real, Santa Clara, CA 95053