by Terry Messman

This is a story about people living in one of the most impoverished places in America, with substandard housing, poor health care, and lowered life expectancy. This is a story about how segregation and racial discrimination harm human beings. And this is a story about how beauty flowers forth from the fields of brutality.

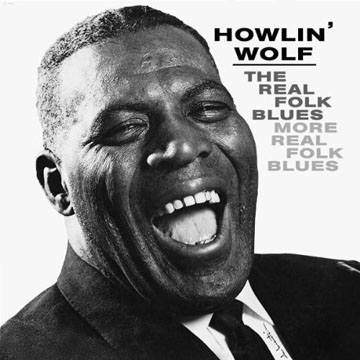

This is a story of the blues. “This is where the soul of man never dies,” as Sam Phillips of Sun Studio said when he first heard legendary bluesman Howlin’ Wolf.

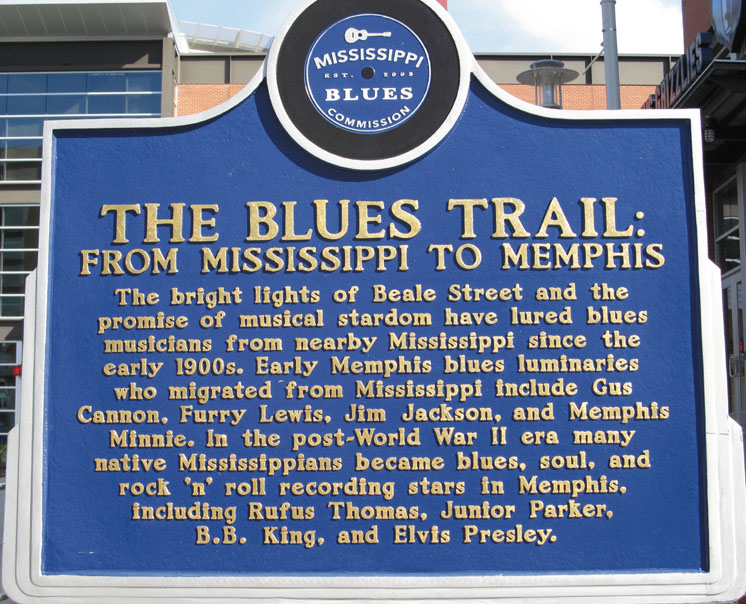

On the Trail of the Blues

“The Mississippi Delta was shining like a National guitar.

I am following the river down the highway

Through the cradle of the Civil War.

I’m going to Graceland, Graceland, Memphis, Tennessee.” — Paul Simon

The Mississippi Delta was shining in sacred light, shining like the National steel-bodied guitar that was played so furiously by one of Mississippi’s most amazing sons — Son House, one of the first Delta blues musicians, a man who played with such heartfelt passion I would have followed that soulful voice anywhere.

Such highly influential blues masters as Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson were first inspired by Son House’s overpowering voice and slide guitar. As my wife, Ellen Danchik, and I drove through the Delta cotton fields that gave birth to the blues, we listened to Son House’s darkly unsettling music, his tortured, raw-edged voice growling in a fever about his search for some kind of redemption.

In our lives, the music of the Mississippi Delta had become so compelling that we had to make this pilgrimage to the birthplace of the blues.

We were on the trail of Son House, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Robert Johnson and Elmore James, following the most legendary blues highway of all — Highway 61 — along the flat floodplains of the Mississippi Delta.

Mississippi gave birth to an overwhelming majority of the world’s finest blues musicians, and we came to visit an amazing network of blues museums, juke joints, birthplaces and gravesites of legendary blues masters — all marked by more than 100 distinctive, dark-blue markers on the Mississippi Blues Trail that honor the legacy of music that flourished under some of the most oppressive economic conditions in the nation.

As we drove on, we listened to Son House sing, almost as a warning:

“The blues ain’t nothing but a lowdown shaking chill

If you ain’t had ‘em, boys, I hope you never will.”

The greatest blues musicians have always captured both the thrill of being alive and the fear of impending death. When House sings, “The blues ain’t nothing but a lowdown shaking chill,” he is giving an unflinching glimpse into an inescapable dimension of the human soul.

Despite his dire warning about the blues, I had dreamed of making this pilgrimage to pay my respects to the brilliant blues masters whose music haunts me, so when James Douglass, a lifelong peace activist and nonviolent theologian who lives at a Catholic Worker house in Birmingham, Alabama, invited Ellen and I to attend a retreat on Gandhian nonviolence with Narayan Desai, Gandhi’s close friend and biographer, my heart leapt.

I knew the time had come to take the blues highway from the heart of the Mississippi Delta all the way to Beale Street and Graceland in Memphis, Tenn.

The Blues and Bondage

After Ellen and I arrived in Jackson, Miss., on March 17, 2012, we drove west to Vicksburg, the city known as the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy” during the Civil War. We were indeed driving down the highway “through the cradle of the Civil War,” just as Paul Simon sang. And that was appropriate, given that one of America’s greatest art forms had grown out of the sweat and toil of sharecroppers laboring on the Delta’s cotton plantations — poor farmers whose ancestors had made the unwilling journey to the United States on slave ships.

As we drove to Vicksburg, we listened to B.B. King’s defiant declaration, “Why I Sing the Blues,” a song that reveals how this music first came to America on slave ships, and was born amidst oppression, hunger, deprivation, and police abuse. King’s glorious, gospel-soaked voice roared out a devastating indictment of our historic legacy of chains and enslavement:

“When I first got the blues they brought me over on a ship

Men were standing over me and a lot more with a whip.

And everybody wanna know why I sing the blues.

Well, I’ve been around a long time. I’ve really paid my dues.”

That is the central paradox of the blues. An art form of joy and radiant brilliance was created by musicians who transformed brutality into beauty, like alchemists of the spirit.

The Blues and the Joys

Yet, the blues aren’t just about having the blues, of course. The blues are also about the joys. Some of this music is tinted with the light blue of melancholy, or drenched in the despondent dark blue of heartache. But so much of it is joyously colored with the hopes, the high times, the wild passions, love affairs, parties, and the exaltation of the human spirit.

Some of the best parties in the world were held by people who labored as sharecroppers all week, and then crowded into a Mississippi juke joint to drink moonshine and dance while a wandering blues musician played slide guitar.

The blues flourished in the midst of grueling hours of labor by hundreds of thousands of workers in bondage to the plantation system. The first blues musicians were as nameless and faceless as the countless sharecroppers who gave their sweat, their blood, their very lives, to a system of economic bondage.

Crossroads of Despair and Hope

The blues grew on the intersection of endless toil and hoped-for deliverance — the crossroads of despair and hope.

Long before the first blues musicians were ever recorded, and achieved a small amount of respect for their musical skills, many were despised even in their own communities, considered worthless ramblers pursuing a morally dubious calling. Yet they went on to create something of lasting beauty. Poor people living in humble shacks on plantations created one of the most important art forms in the world.

It’s all there in the B.B. King song we’re listening to as we drive north on Highway 61 out of Vicksburg. “Why I Sing the Blues” is an amazing political outburst that begins its journey on a slave ship, then moves forward through time and space into modern American cities where the singer endures harrowing poverty and the heartless indifference of welfare officials.

“I’ve laid in a ghetto flat, cold and numb

I heard the rats tell the bedbugs to give the roaches some.”

Trying to escape poverty, he only runs into lying politicians with false promises of affordable housing. Anyone who has ever been poor, or tried to help homeless people, knows what happens next. He seeks help at the welfare office and is shot down by their stonehearted denial:

“I thought I’d go down to the welfare to get myself some grits and stuff

But a lady stand up and she said ‘You haven’t been around long enough’

That’s why I got the blues.”

Finally, after King’s fluid guitar echoes his anguished voice in crying out in anger and heartbreak, he delivers a deeply moving lamentation for a blind homeless man who is criminalized by the cops (the “rollers”) simply because he asks for a dime:

“Blind man on the corner begging for a dime

The rollers come and caught him and throw him in the jail for a crime

I got the blues, mm, I’m singing my blues.”

B.B. King’s stinging guitar and richly expressive voice expose the entire history of a nation’s shameful mistreatment of African Americans, poor people and the disabled. His song should be claimed as the national anthem for all poor and homeless Americans.

‘The Longest Road I Know’

As we continue driving north on Highway 61 on our way to Leland, Miss., we listen to Mississippi Fred McDowell sing, “Lord, that 61 Highway is the longest road I know.”

For countless Mississippi residents, the highways and railroad tracks, the train depots and bus stations, were passages leading away from a life of hardship to better opportunities in Memphis, Chicago and Detroit. Many great blues musicians traveled these same paths as they left behind hardscrabble lives working as sharecroppers on plantations and playing in Mississippi juke joints, and headed on up to Memphis, and points north.

For some, it turned into a highway of loneliness and unfulfilled dreams. For others, it led to liberation. Sometimes it led to the valley of the shadow of death.

Mississippi Fred McDowell sang:

“Lord, if I have to die, baby,

Before you think my time have come,

I want you to bury my body out on Highway 61.”

For all of its overwhelming influence on the music of the whole world, the Mississippi Delta is a relatively small area, only about 60 or 70 miles wide by 200 miles long, bounded on the west by the Mississippi River and on the east by the Yazoo River, and extending from the cities of Jackson and Vicksburg in the south, about 200 miles north to Memphis, along either Highway 61 or Highway 55.

The Delta is the flat floodplain where the Mississippi River overflowed its banks over and over again throughout history, creating some of the most fertile topsoil anywhere, some of the richest cotton plantations, and some of the most impoverished farm laborers and sharecroppers in the nation.

Blues Music and Civil Rights

Strange to say, I love blues music for many of the same reasons I’ve always loved the U.S. civil rights movement. The unimaginable bravery of Southern civil rights workers who endured beatings, jailings, bombings and martyrdom in their fight for freedom is mirrored in the way that the beauty of the blues grew out of brutal conditions.

Brought in chains from Africa to toil without pay or freedom or human rights on Southern plantations, African Americans endured a barbaric form of slavery that prevailed far longer in the United States than most other civilized nations.

After the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, African Americans would suffer the cruel oppression of racial discrimination and segregation for another century until they took their destiny into their own hands, and formed a freedom movement that would overcome staggering odds to topple the system of segregation. I still consider the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s to be the bravest and most beautiful movement in our nation’s history.

But the blues blossomed into a beautiful art form decades earlier in our history, back in the 1920s and 1930s, while segregation was still fully in effect. This music, which was to become one of the most important and lasting American art forms, was born in the midst of racism and poverty, and flourished despite the violence of night riders, lynchings, terribly inadequate schools, wretched health care, and the exploitative conditions faced by sharecroppers picking cotton or driving tractors for such low wages that their debt only grew larger, year after year.

It is a testament to the human spirit that the breathtaking beauty of the blues and the heroic courage of the civil rights movement were both able to arise out of the worst conditions of deprivation and hardship. Both movements gave this nation so much it is almost beyond belief.

Paul McCartney’s song “Blackbird,” from the Beatles White Album, captures how this beauty was born in the dark night of the soul:

“Blackbird singing in the dead of night

Take these broken wings and learn to fly.

All your life, you were only waiting

for this moment to arise.”

A photograph taken by Son House’s manager, Dick Waterman, captures something essential about the meaning of blues music in America for me. After his “rediscovery” in the 1960s, Son House was photographed standing next to the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. But the bell designed to ring out in freedom is cracked. The blues were not born in a free land for African-Americans. A tragic crack ran through it from the beginning.

Blindness and the Blues

As we continue driving north on the Mississippi Blues Trail, McCartney is still singing a song of profound meaning:

“Blackbird singing in the dead of night,

Take these sunken eyes and learn to see.

All your life, you were only waiting

for this moment to be free.”

On top of economic hardships and racial discrimination, so many great blues singers suffered terrible illnesses, premature deaths, and disability and blindness, either from birth, accident, or disease.

As unfair and miserly as disability benefits are today, imagine being blind in Mississippi or Alabama 70 years ago. Except for the kindness of families who often were very poor themselves and barely able to survive, what help was available for a Black child or adult afflicted with blindness?

Yet despite these overwhelming obstacles, some of the very finest blues musicians of all time were blind. These musicians faced life with what McCartney called “sunken eyes” and yet went on “singing in the dead of night,” waiting for their “moment to be free.”

We’re not talking about also-rans who overcame blindness to create decent but unexceptional music. We’re talking about legendary blues geniuses and masters. In Blues Guitar Heroes, a 2010 English publication, Eric Clapton was asked what advice he had for today’s aspiring musicians. He said, “Listen to the past.”

Clapton explained that most people remain unaware of where the blues came from, and said that people today should “go back and listen to Robert Johnson, Blind Blake, Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Willie Johnson and Blind Willie McTell.”

Stunningly, Robert Johnson was the only blues master on Clapton’s list who was not blind. And his list didn’t even include Blind Lemon Jefferson, one of the very first blues pioneers and an incredibly gifted guitarist; nor Blind Rev. Gary Davis, the impassioned, gruff-voiced singer and virtuoso guitarist who inspired so many musicians in the 1960s; nor Sleepy John Estes, an exceptionally fine blues vocalist who lost the vision in his right eye as a boy and became completely blind in both eyes when he was middle-aged; nor Sonny Terry, the sightless harmonica player who performed with Brownie McGhee; nor Ray Charles, the greatest blues/soul/gospel singer of his generation.

The birth of such beauty out of such tremendous suffering is the same thing we saw happen again and again in the civil rights movement. The human spirit arrives at the crossroads and, instead of going down the roadway to despair, musicians found another path, where suffering is transmuted into joy.

Highway 61 Blues Museum

We finally reach Leland, Mississippi, at sundown on our first day on the road. Leland is a small town located on the crossroads of Highway 61 and Highway 82. When we arrive, the Highway 61 Blues Museum is closed, and we’re downcast to find that we have missed out at our first stop on the Blues Trail. We realize we might never make it back to see this museum.

But we see a sign on the museum door with a phone number, so we dial it and we’re overjoyed when Billy Johnson, the incredibly friendly curator of the Highway 61 Blues Museum, tells us he’ll drive right down to give us a private tour.

Ellen and I found that level of friendship and hospitality virtually everywhere we went in Mississippi. Friends in Oakland, black and white alike, had warned us that this trip might be dangerous, but time and again, the warmth and decency of the people we met in Mississippi — black and white alike — were wonderful to experience.

As we waited for Johnson to arrive, we went to look at the four large blues murals on the walls of nearby buildings that honor local blues musicians. Many hometown heroes hail from the Leland area, and on the murals, these local blues legends never left, and they never died. They are enshrined just as they were in their glory days, larger than life, still playing and singing their hearts out.

Only a half-block from the museum, a building-sized mural portrays local legends who became international stars, including Johnny and Edgar Winter, renowned blues singer and guitarist Little Milton, Jimmy Reed, and James “Son” Thomas.

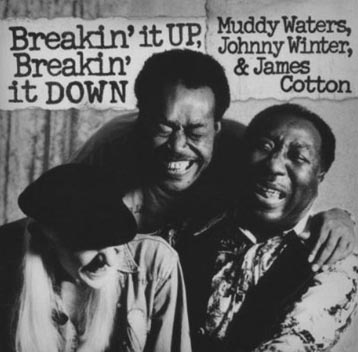

Johnny Winter, the long-haired, albino bluesman who is one of the most sensational guitarists of our era, and who earned an honored place in blues history by producing and playing on Muddy Waters’ Grammy-winning comeback albums, is one of the only white musicians in the Blues Hall of Fame.

Winter grew up in Texas, but he was born in Leland, Miss., and his family has deep roots in this small town. His father was the mayor of Leland. In addition to being depicted on the mural, Winter’s musical journey is also profiled on a State Blues Marker a block from the museum. Winter composed “Leland Mississippi Blues” on his self-titled first album for Columbia back in 1969. He sang:

“I’m going to Leland, Mississippi, mama

You all know that’s where I come from

Right down on the Delta, man.”

Now Winter is always “right down on the Delta, man” — profiled on the blues marker, displayed on the mural, enshrined in a special exhibit in the museum.

When Museum Curator Billy Johnson arrives, we realize he has uncomplainingly interrupted his supper to generously give two strangers a private tour. When he finds out how excited we are to see the museum, he refuses to let us pay the normal admission.

Johnson is warm, friendly, fiercely loyal to his Mississippi roots, and dedicated to keeping the spirit of blues music alive in Leland. He has been a mainstay behind the creation of the blues murals, and operates his museum as a labor of love run almost entirely by volunteers.

Johnson is highly knowledgeable about every blues musician I ask about, and his great love for the music overlaps with his love for his home state as he tells us the remarkable truth that literally hundreds of internationally famous musicians come from Mississippi.

So who is his personal favorite, I ask. Without hesitation, Johnson answers, “Jimmy Reed,” and shows us his well-designed museum display of Reed.

Reed was born on a plantation near Dunleith, Miss., and grew into an influential singer and guitarist who racked up an amazing number of hits on the pop charts — far more hits than blues legends like Muddy Waters or Elmore James. His songs include “Bright Lights, Big City,” Honest I Do,” “Big Boss Man” and many others.

Yet even as his songs shot up the charts, Reed’s life fell apart. He plunged into out-of-control alcoholism and uncontrollable epileptic seizures, The blues seemed to reach out and claim this man. His record company went out of business, and he released one last single, a song with the tragically ironic title, “Don’t Think I’m Through.”

His downfall from epilepsy, alcoholism and hardship ended in one of the terribly hard deaths that seem to haunt the blues. Reed died on August 29, 1976.

But in Leland, Miss., Jimmy Reed still lives on in the Highway 61 Blues Museum and his larger-than-life mural image still plays the blues in living color. One of the large outdoor murals is devoted exclusively to Jimmy Reed.

A nearby mural is devoted to B.B. King from nearby Indianola, and spans five decades of King’s amazing career.

B.B. King plays for Obama

After lovingly looking at every exhibit in Johnson’s fine museum, it was time to leave Leland and head east on Highway 82 to Indianola, Miss., the home of one of my all-time heroes, B. B. King.

Less than a month before we visited the Mississippi Blues Trail, B.B. King played a blues concert with several other musicians at the White House for President Obama, a concert broadcast on PBS in honor of Black History Month.

“This music speaks to something universal,” Obama said at the concert. “No one goes through life without both joy and pain, triumph and sorrow. The blues gets all of that, sometimes with just one lyric or one note. “

That is certainly true of King’s brilliant playing. King is now 86, but he still is performing hundreds of concerts a year. For Obama, he played “Let the Good Times Roll,” and his exquisitely haunting signature hit, “The Thrill is Gone.”

B.B. King has won nearly every award a poor sharecropper from Indianola, Miss., could ever have dreamed of earning. He’s been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the National Medal of Arts, the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and the Kennedy Center Honors award. He’s received an amazing 15 Grammy awards over the years, and was elected to both the Blues Hall of Fame, and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. In 2010, in a special issue of an English publication, Blues Guitar Heroes, King was chosen as the finest blues guitarist in history, “the true living embodiment of electric blues.”

‘One Kind Favor’

As we drove to Indianola, Ellen and I listened to “One Kind Favor,’ a record of exquisite beauty that King released in 2008 at the age of 83. “One Kind Favor” is a glorious return to his roots in the pure blues, and he covers songs by the most deeply authentic blues masters, including the Mississippi Sheiks, T-Bone Walker, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and Lonnie Johnson.

Despite all these incredible songs, on the drive to Indianola, we played only one song over and over and over — “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean,” a song written by one of the very first bluesmen of all, the legendary Blind Lemon Jefferson.

King’s voice and guitar on “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” are exceptionally moving. He sounds like an interfused mix of growling bluesman and inspirational gospel singer. His amazing vocal performance can only come from the heart and soul of one who sees and feels, all too clearly, the shadows of looming death.

I hesitate to quote from this song because the lyrics are very dark. But King’s music gives us a fundamental truth about the human condition. While other forms of music may focus almost solely on love, romance and good times, blues musicians have always tried to express the whole truth, the whole range of humanity’s emotional experiences — not only joy and love, but also the heartbreak and anguish of the human soul.

B.B. King is gentle and modest, friendly and open almost to a fault, even after he has signed his 300th autograph of the evening. His music conveys such a sense of joy and gladness that it leaves you happy even when he is singing from the deepest, darkest corner of the soul. But King began life working as a sharecropper, and he truly has paid his dues. So he can sing from a deep, dark-blue dimension of the soul with revelatory force — the dimension of heartache and loss.

Many kinds of heartache

Heartache doesn’t just come when a love affair has ended in sorrow, or when someone wakes up feeling bad, or they’re broke and the wolf is at the door. The blues can also come from a deeper source of sorrow. None of us get out of this world alive, as the great Hank Williams sang on his very last song before his own untimely death.

In a state like Mississippi, hard lives, poor pay and inadequate health care ended all too often in sickness and early death. The great blues singers didn’t shy away from these unmentionable topics.

So as we drive to Indianola, we play “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” over and over and over.

“Did you ever hear the church bell tone?

Did you ever hear a church bell tone?

Then you know that the poor boy’s dead and gone.”

King sings these stark words with haunting fervor and intensity. His voice is powerfully expressive and utterly beautiful. This song absolutely knocks me out every time I hear it.

It’s not just because King is singing a sorrowful truth we all must face. Rather, hearing this song somehow makes me feel all the joy and sorrow of being alive. I admire King for singing this truth right out of the depth of his heart and soul. It seems crazy to say, but each and every time I hear B.B. King sing this song, I feel so happy, so exhilarated, so inspired.

By now in his career, almost everyone realizes what a great and hugely influential guitarist B.B. King is. But what a singer this man is. I am astonished that an 83-year-old veteran of a life lived at breakneck pace could sing a song this powerfully, this evocatively.

As we enter Indianola, a small town of about 10,000 people where King spent the greater part of his youth, “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” is playing for the seventh time in a row:

“Well, my heart stopped beating and my hands are cold.

Well, my heart stopped beating and my hands are cold.

I believe just what the Bible told.”

How in the world can a song so drenched in deep-blue reflections on mortality make me so happy? With this unforgettable meditation on the final chapter of the singer’s earthly life ringing in our ears, Ellen and I visited the street corner that honors the very beginning of King’s life as a musician.

The teenaged B.B. King first began performing gospel and blues songs in public on the corner of Church Street and Second in Indianola. In 1986, King pressed his footprints and handprints into the same patch of sidewalk where he once played as an unknown street musician. The street corner also was memorialized with a State Blues Marker and a large portrait of the young King on the wall.

Next, we walked one block away to see a huge, colorful painting of B.B. King on the wall of a building. Finally, unable to contain our excitement any longer, we walked to one of the key sites of our pilgrimage, the B.B. King Museum, which opened in September 2008.

Just as King is one of my very favorite musicians, his namesake museum is one of the finest museums I have ever seen. The B.B. King Museum stands at the site of the 1910 cotton gin where King once worked, and it is strikingly attractive.

The museum utilizes multi-media displays to brilliant advantage, but, most importantly, it is perhaps the best single place in Mississippi to discover how the beauty of the blues emerged from the poverty and grinding hardships of life in rural Mississippi.

The museum does a wondrous job of using multimedia exhibits to show the progression of B.B. King’s career through the years, and to show the presidents and Popes he has performed for, and the staggering number of blues musicians and rock musicians he has directly inspired. You can listen not only to many of King’s own songs but also to the music of dozens of his musical descendants — the rock and blues musicians he inspired.

It is an extremely well-thought-out museum and conveys the joy of the blues in a brilliant display of storytelling, short films, vintage memorabilia, and wall-sized photographic displays that take you on King’s odyssey from the Mississippi farmlands to the sophisticated night clubs on Beale Street in Memphis.

I fell into a state of awe and inspiration the moment I entered the first stop on the museum tour and watched a short film of King’s life. As the film begins, B.B. King, now one of the biggest musical superstars in the world, visits the Mississippi Delta cotton fields where he was born. Although King has reached a peak of international acclaim, he still returns to the small town of Indianola every June to play a free blues concert.

‘Depressed by the Oppression’

Even though he expresses affection for his Indianola roots, B.B. King’s journey into the blues was rooted in poverty, long hours of backbreaking toil in the cotton fields and a segregation system aimed at breaking people’s spirits.

Rev. David Matthews, a Baptist minister in Indianola, says on the film, “The blues were born and not written, because in those days it was oppression and you were depressed by the oppression. Black folks had no rights. It was badder than bad. I was there. I know.”

Yet, in King’s odyssey from Indianola to international icon, we once again see how beauty and hope and love flower forth from the fields of heartbreak, hardships, involuntary servitude and racism.

Eric Clapton, one of King’s many famous admirers and students, described the way music transmutes hardships into hope. “The principle of listening to the blues is, you get joy. It’s a music of hope and triumph over adversity. That’s what B.B. King has shown us most of all.”

Transforming sorrow and deprivation into joy and beauty sounds like a lovely idea, but the reality was that simply surviving was often a life-and-death struggle, given the economic exploitation faced by sharecroppers in Mississippi.

The B.B. King Museum is rooted in the cotton fields of the Mississippi Delta, and its first set of exhibits and films portray the farmers and sharecroppers who worked long hours for low pay in a desperate effort to survive.

Riley B. King was born in 1925 in a small cabin on a cotton plantation between Indianola and Greenwood, Miss. In his 2005 biography, B.B. King: There Is Always One More Time, David McGee writes, “Working in the fields for long hours, King learned about the economics of sharecropping, how the paltry wages paid for backbreaking work underwrote the plantation owners’ opulent lifestyles, and perpetuated the sharecropper’s misery.”

A film in the museum illustrates this point by showing that no matter how hard sharecroppers labored, they faced high interest rates and frequent trickery that left them in debt that grew year after year.

‘From Can to Can’t’

Rev. David Matthews, an African-American Baptist minister in Indianola, described how this economic captivity ensnared the poor farmers, no matter how many hours they worked. Sharecroppers worked in the cotton fields “from can to can’t” every day, meaning they began work as soon as they can see daylight, and worked until they can’t see at night.

All those hours of work were to no avail if the economic system was rigged against sharecroppers so as to keep them from ever getting out of debt. Rev. Matthews said, “They got you on the price of the groceries. They got you on the grade of the cotton you sold. They got you at every corner.”

At age 12, King saved money from his $15 monthly wage on the farm to buy a used acoustic guitar. The guitar gave him a first glimmer of a new life — an escape from the trap of never-ending work for ever-growing debt.

The film and exhibits not only display the economic hardships he faced, but also the oppressive system of segregation he endured. King had white friends in Mississippi and worked for a white farmer, Flake Cartledge, a “fair and liberal” man who treated him humanely and with much respect. Still, throughout his youth, the state of Mississippi was ruled by a cruel form of racial discrimination.

In the film showing King’s homecoming to Indianola, a white former governor of Mississippi states bluntly that the state had “allowed itself to be overcome by an evil system of segregation.” The fact that a former Mississippi governor condemned that system so forthrightly is one indication of how the South has changed.

In a major public address in 2004, William Winter, the Democratic governor of Mississippi from 1980-1984, publicly thanked the civil rights movement for helping to reform the South. Gov. Winter said, “Impressive advances have been made in race relations since the tumultuous 1960s when the South was freed from the burden of defending the indefensible system of racial segregation. For that, we Southerners, and especially we white Southerners, owe a huge debt to valiant civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King and John Lewis and Medgar Evers and so many others.”

Winter added, “All of us were prisoners of a system that enslaved us all and that dictated how we lived our lives. It caused us all to live in fear and mistrust and ignorance of each other. The tragedy is that freeing ourselves of that bondage took so long and caused so much needless and useless suffering and violence.”

Music as an Escape

Music was a form of escape for many white and Black sharecroppers in the Delta — if not economic escape, at least spiritual or emotional escape.

Rev. Matthews described music as a saving grace for King and many other plantation workers, “A pacification for black folks was singing the blues and singing spirituals so they wouldn’t drift into nothingness.”

Music enabled King to leave an anonymous life toiling on the Delta plantations and take his first steps into worldwide fame when he traveled to Memphis, a thriving scene where the blues, soul, country and rock ‘n’ roll were all played and mixed together and cross-fertilized.

In his invaluable tour book, Blues Traveling: The Holy Sites of Delta Blues, author Steve Cheseborough explains what an important destination Beale Street was for people in King’s era. He writes, “For almost a century, Memphis’s Beale Street was the focal point not only of the Mississippi Delta, but of black America, eclipsing even Harlem in its crowds, excitement, and music.”

King soon began recording in the famed Sun Studio in Memphis where country, rock and rockabilly greats including Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, Charlie Rich and Carl Perkins were first recorded. In the early 1950s, Sun Studio began recording a dazzling list of future hall-of-fame blues musicians, including Howlin’ Wolf, Little Milton, Junior Parker, James Cotton — and B.B. King.

In Memphis, the young Riley B. King was transformed into B.B. King. He began working at radio station WDIA as a singer and disc jockey, where he was nicknamed the Beale Street Blues Boy, later shortened to Blues Boy King, and finally to B.B. King.

The final stages of the museum tour remain vivid in my memory. They show the worldwide stage that King ascended in his later years, playing with Eric Clapton and U2, being honored at the White House, and performing at the Vatican’s Christmas concert, where he presented the Pope with his famous guitar, “Lucille.”

A crucial step in his growing fame came in the 1960s, when King first played for large audiences of white countercultural youth in San Francisco’s Fillmore West. Up until then, most of King’s audiences had been overwhelmingly African American. He was very confused that his manager had booked him to play at the Fillmore before a huge audience of long-haired, white, young people.

King recalled that he’d never played for that kind of people before, so he just played the best blues he knew how. When he finished, he received rapturous applause and standing ovations that went on and on. He was shocked and moved to tears of joy. So, he played encore after encore, and the wild applause and adoration of his newfound white fans stunned the veteran bluesman.

The hours we spent in the B.B. King Museum were so exhilarating, it was hard to move on, but it was almost dark, and we had to make it that night to Clarksdale, Miss., home of the Delta Blues Museum.

We drove north on Highway 61 through a dark, stormy night, and it began to rain heavily as we finally reached the crossroads leading into Clarksdale.

Clarksdale is haunted by the spirits of the blues masters of the past. The great Son House learned to play guitar in Clarksdale, and Muddy Waters found lasting inspiration by listening and learning as House played the blues at a Clarksdale-area juke joint. Junior Parker and Ike Turner also played here. John Lee Hooker was a native of Clarksdale until he left home at the age of 14 and went to Detroit where he became one of the most widely recorded blues musicians of his time.

Reaching the Crossroads

As we reach the intersection of Highway 61 and Highway 49, our spirits rise at the sight of giant blue guitars on top of a large light pole and a highway sign that says, “The Crossroads.” Signs for Highways 61 and 49 are perched atop the whole display.

The blue guitars mounted on the Crossroads sign make up a well-known symbol of the Mississippi Blues Trail — it’s on the front cover of our Mississippi tour guidebook. Yet, in all likelihood, this is not the legendary crossroads that Robert Johnson sang about so eerily in “Cross Road Blues.”

“I went down to the crossroad, fell down on my knees

Asked the Lord above, “Have mercy, now save poor Bob, if you please.”

Even though the crossroads that Robert Johnson wrote about were very likely some lonely, deserted intersection out in the country, this crossroads at Clarksdale is the intersection of the legendary Highways 61 and 49 which so many blues musicians sang about.

In Blues Traveling, Cheseborough writes: “This Crossroads is important for what it is: the intersection of the two main blues highways, the roads on which countless blues singers and other Delta folks walked or rode as they sought work, migrated north, or just rambled.”

On the drive into Clarksdale, we listen to Robert Johnson’s high, haunting voice on his original version of “Cross Road Blues,” followed by Eric Clapton’s lightning-fast guitar runs on Cream’s version of “Crossroads” on their “Wheels of Fire” album. Johnson’s powerful lyrics have made the myths live on, whether it’s the legend of a lonely bluesman sinking down on his knees in a desolate area, or selling his very soul for guitar mastery.

“Standing at the crossroad, baby, rising sun going down

I believe to my soul, now, poor Bob is sinkin’ down.”

Muddy Waters at the Crossroads

Perhaps the single most influential bluesman in the world found his own crossroads in Clarksdale. Muddy Waters had lived in a tumbledown cabin on Stovall Plantation, a few miles outside of Clarksdale, for 25 years, picking cotton and driving a tractor for 22 and one-half cents per hour.

Waters lived with his grandmother in the small, wooden cabin on this plantation from the time he was three years old, until he quit his job and left Clarksdale after having a dispute with the plantation manager over his poverty wages.

In 1943, when he was 28, Waters went to the Clarksdale Station and boarded a train for Chicago, setting off on what has now become a nearly mythical journey for the blues. In a few short years, Waters assembled an outstanding band that began transforming the Delta blues into the modern electric blues, the music that would be heard all around the world.

Waters began recording a series of legendary blues recordings for Chess Records in Chicago, with himself and Jimmy Rogers on guitar, Otis Spann on piano, Willy Dixon on bass, and one of the most phenomenal blues players of all time, Little Walter, on harmonica.

In a few short years, the electric blues perfected by Muddy Waters, and also by Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson and Little Walter would travel across the Atlantic Ocean to England and inspire a new generation of rock musicians.

“The blues had a baby, and they named it rock and roll,” is how Muddy sang of the foundational role the blues played in jumpstarting the British Invasion.

Delta Blues Museum

As we drive up to the Delta Blues Museum, we pass the old Clarksdale Station, built in 1926, the very railroad station where Muddy Waters bought that ticket of destiny to Chicago in 1943.

The Delta Blues Museum is located at “1 Blues Alley” in the old Freight Depot, a brick building constructed in 1918. It hosts many wonderful displays that help to pierce the veil of history and take us back in time to the forgotten street corners and Mississippi juke joints where both famous and obscure musicians played for decades, as the Delta Blues slowly evolved.

The small cabin that was Muddy Waters’ home on Stovall Plantation was taken down, moved and reassembled. Now it is on display inside the Delta Blues Museum. Ellen and I make a beeline for the rough-hewn home built from axe-cut planks, and soon we are sitting in the cabin and watching a movie of his life.

It is a truly moving experience to sit in this roughly built little cabin, and watch Muddy Waters leading his legendary blues band on a tour through Europe, playing classic songs like “I Can’t Be Satisfied,” “Rollin’ Stone,” Louisiana Blues,” “Trouble No More,” “Mannish Boy,” and “Rollin’ and Tumblin.’

It is awesome to realize we’re sitting in the very cabin where Muddy’s blues were first recorded back in 1941, when folklorist Alan Lomax recorded Waters for the Library of Congress.

From these humble beginnings, Muddy then took the country-style Delta blues to Chicago, electrified the music so it could be heard in the noisy bars on Chicago’s South Side, and then took his legendary band to Europe, and electrified the world.

The Rolling Stones took their name from the Muddy Waters song, and the Stones always championed his work, for which he was very grateful. So many of the great British Invasion bands found their greatest inspiration in the blues music recorded by Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf for Chess Records.

When the Beatles first visited the United States, they told interviewers of their great admiration for Muddy Waters, and the Stones visited Chess Records in Chicago, the great shrine where the blues music they loved had originated. Many of the finest English rock groups — including the Stones, Cream, the Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, and the Animals— paid the highest tribute to U.S. blues musicians by recording their songs.

At the end of our tour, we went to the museum’s gift shop and bought the CD entitled “Muddy Waters: The Complete Plantation Recordings,” the first recording of Muddy playing the Delta Blues, along with the interviews Lomax taped with him at the historic session.

I’d wanted to have this CD for a long time, but I made myself wait until I could buy it at the Delta Blues Museum. I went back into Muddy’s cabin to open the CD booklet, and saw photos of the same cabin where I was sitting. Muddy played all the brilliant music in this recording on the porch of this cabin when he was still a sharecropper and tractor driver.

One of the first songs he ever sang is on this CD, “I Be’s Troubled.” It’s nearly a perfect statement of the rambling ways of blues musicians, and describes how loneliness and a worried mind build up to a strong desire to escape. Muddy sang these lyrics in 1941, and listening to them now, we can almost feel the momentum building up so powerfully that Muddy would leave Mississippi for good only two years later. Muddy sings:

“Well if I feel tomorrow, like I feel today

I’m gonna pack my suitcase, and make my getaway.

Lord I’m troubled, I’m all worried in mind

And I’m never being satisfied, and I just can’t keep from crying.”

Muddy learned to play the blues here in Clarksdale and his major inspiration was Son House, one of the key founders of the Delta Blues. Waters told Down Beat magazine, “He was my idol coming up in my young life, Son House was.”

Son House was playing at the same place in Clarksdale for four weeks in a row, and Muddy was there every single night, listening to House’s incredibly powerful, soulful, roughly expressive voice and his slashing attacks on his bottleneck slide guitar. Waters said that when he first heard House playing, it was so overpowering and moving, that “I should have broke my bottleneck.”

“I was there every night,” Waters later told Down Beat. “You couldn’t get me out of that corner, listening to him and what he’s doing. Really, though, it was Son House who moved me to play. I was really behind Son House all the way.”

So Ellen and I visited the Son House exhibit in the Delta Blues Museum. It was an extraordinary experience — the spiritual peak of the entire trip for me — just to see so many photographs and other artifacts of Son House I’d never seen anywhere before, and to contemplate the life and music of perhaps the most deeply soulful of all the great Delta bluesmen, in the very town where he played for Muddy Waters.

The museum exhibit traces Son House’s nearly unbelievable journey through the blues. Along, with his friends Charley Patton and Willie Brown, Son House was the father of the Delta Blues, the man who most inspired Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson. His impassioned singing is one of the most intense experiences in the blues, and to many who witnessed House playing, he seemed like a man possessed.

A trancelike possession

Thrashing away on his National steel guitar, House would launch himself into the blues with an intensity that seemed to put him in a state of trancelike possession, as if he were having a seizure — a musical seizure that would, in later years, deeply move his listeners, whether in New York coffeehouses or European capitals.

When he was a young man, Son House preached in Baptist churches, and for the rest of his life, he found himself torn between the emotional extremes of preaching in church or “preaching the blues,” as he called it. He turned away from his calling as a Baptist preacher, but often felt intense anguish over his choice to leave that calling to play the blues.

The museum displays many of Dick Waterman’s wonderful photos of Son House following his “rediscovery” by blues scholars in the early 1960s. Back in the 1930s, Son House had made a few classic blues recordings for Paramount Records, and then was recorded by folklorist Alan Lomax in 1941-1942 for the Library of Congress. The museum even has on display the old, rusted sign from Clack’s Grocery, where Lomax recorded Son House on Sept. 3, 1941.

After those few tantalizing recordings, Son House left the scene and seemed to fade away into oblivion. He recorded nothing further, and even set his guitar aside for decades. If anything, his disappearance into obscurity only made his legend all the more compelling.

Then, in 1964, at the height of the folk revival, three young blues researchers, Dick Waterman, Nick Perls and Phil Spiro, discovered House living quietly in Rochester, New York, and convinced him to take up the blues he had laid aside more than 20 years earlier. Waterman managed Son House for the rest of his life, getting him a recording contract with Columbia Records, and arranging appearances at the renowned Newport Folk Festival, the New York Folk Festival, Carnegie Hall, and the college and coffeehouse circuits. In 1967, House made greatly heralded concert appearances in Europe, as part of the American Folk Blues Festival.

Son House is very strong medicine, not for everyone, and definitely not a starting point for those just getting into the blues.

But it is mesmerizing to listen to that rasping, rough-hewn voice, so loud and soulful it could lift your spirits or wake the dead. It’s a paradox to say his music can lift your spirits, though, because he sang about the real, downhearted blues, the blues as felt by someone who knew sorrow and torment all too well.

“Some people tell me the worried blues ain’t bad

But it’s the worst old feeling, Lord, I ever had.”

His music expressed all the loneliness of the human condition, the heartrending sense of loss.

“Don’t a man feel bad when the Good Lord’s sun go down?

He don’t have nobody to throw his arms around”

House sang those words in “Walkin’ Blues.” But things grew dramatically worse for him one day when he stopped walking, laid out flat by strong drink.

Frostbitten and Blue

One freezing night in January 1970, Son House walked home after a night drinking in a Rochester bar, according to a new biography of House by Daniel Beaumont entitled, Preachin’ The Blues: The Life and Times of Son House.

He passed out and crumpled, unconscious, on the side of the road and lay unconscious in the snow all night until someone found him lying there and called for an ambulance.

House was in the hospital for several days, and when he was released, his hands were so badly frostbitten that he missed out on the greatest career opportunity of his life. The famed British blues musician Eric Clapton loved Son House’s music and wanted him as the opening act for Clapton’s concert with Delaney and Bonnie at the Fillmore East.

According to Beaumont’s biography, his manager had to turn down playing at the Clapton concert because House’s hands were too severely damaged. Beaumont writes that, as a result of this misfortune, “House missed what would have undoubtedly been the biggest performance — and payday — of his career, losing out on the ringing endorsement of Eric Clapton, an endorsement that would have sent legions of Clapton’s fans to the record stores in search of Son House’s recordings.”

In his later years, Son House stopped performing, and he died in Detroit in 1988. On his grave there is a picture of House holding his National steel guitar, and this inscription: “The Father of the Blues.” On one side of his gravestone is a tremendously haunting song lyric that says it all:

“Go away Blues, go away, and leave poor me alone.”

On the reverse side of House’s grave is Dick Waterman’s description of House singing: “It was as if he went into a trance and somehow willed himself to another time and another place.”

Waterman managed so many prominent blues stars, and heard so many others, but he would always say that House’s performances were the most majestic of all. Waterman believes House is at the very top of the Blues pantheon, and it is tremendously moving to read this tribute he had inscribed on his friend’s grave:

“Other blues singers, great in their own way, would watch Son House sing the blues and just shake their heads. He was the benchmark of their artistry. He was the measuring stick by which blues singers are to be forever judged. On October 19, 1988, every blues singer in the world moved up one place in the rankings. There was a vacancy at the very top.”

In the Delta Blues Museum gift shop, we bought Waterman’s beautifully illustrated book Between Midnight and Day: The Last Unpublished Blues Archives. The book has highly evocative photographs of the blues musicians Waterman has worked with, along with his personal memories. In 2000, Waterman was inducted into The Blues Hall of Fame for his fine work managing blues musicians.

Abe’s and Elvis

That night, we drove back to the Crossroads and ate dinner at Abe’s BBQ, a renowned barbecue restaurant that has been located at the Crossroads since 1937. The food was incredibly delicious, and among all the music-themed posters we saw a photo of Elvis Presley.

When Ellen innocently asked if Elvis was supposed to have eaten there, she was quickly assured that Elvis enjoyed eating at Abe’s, and that led to several customers sharing their Elvis stories. I mentioned this earlier, but one of the best surprises on this trip was the warmth and friendliness of so many people we met in Mississippi.

Even so, this night was really special. A banker and his schoolteacher wife, and two truckers who seemed to know more about Mississippi music than many of the museum guides we’d met, began regaling us with stories about Elvis. I could have listened all night long, and we almost did.

These Mississippians were very knowledgeable about the blues, rock, gospel, country and soul music. As they talked about the different kinds of music that are enshrined in Clarksdale and up north in Memphis, I reflected on what a melting pot for music the South really is.

All these kinds of music and diverse musicians influenced and inspired and taught one another, and the South mixed all these different ingredients into brilliantly inventive new combinations.

When we told our fellow diners that we were driving into Memphis right after dinner, we were told with great enthusiasm to check out the Stax Soul Museum, the Memphis Rock and Soul Museum, the legendary Sun Studio — and Graceland.

At that point, Graceland was not even on our schedule. I wanted to see the Stax soul museum and hear music at the B.B. King Club in Memphis. But I soon discovered how much Elvis is revered in Memphis.

With great passion, sincerity and knowledge, the truck drivers, and the banker and his wife, described Elvis Presley’s music, his life, his generosity to charities, the gold records lining two long corridors in his home at Graceland. They described Presley’s musical versatility, not just in jumpstarting rock and roll, but also his love of singing the blues, ballads, country and especially, gospel. I was told that Elvis had as many gold records for Gospel recordings as for rock and roll at Graceland and that I must go see them.

So Ellen and I listed all the museums and blues clubs we wanted to see in Memphis, and we asked the diners at Abe’s what we should see: “GRACELAND!!” was the unanimous answer.

After a few hours of driving, we got into Memphis a little before midnight, feeling a bit downcast because we’d have to wait until morning to see anything. Wrong! Beale Street was still jumping, and in the next three hours, we bought Blues CDs and T-shirts at the B.B. King store on Beale Street, and then went next door into B.B. King’s, a restaurant, bar and blues club that is a monument to how much lasting impact his music has in Memphis.

The Memphis Blues Masters

Then we went across Beale Street to the Blues Hall Juke Joint and spent the next two hours entranced by the high-spirited blues of The Memphis Blues Masters. It was nearly a perfect place to hear live blues, in this overcrowded club whose walls vibrated as the thunderous guitars, keyboards, drums and saxophone wailed out glorious renditions of “Soul Serenade” and “Down Home Blues.”

The Blues Masters play on Beale Street all the time, and they locked into superb, tight rhythms, and then, one by one, each of the Blues Masters stepped forward to take solos. The lead guitarist killed me, a big, overweight guy dressed in way, way casual attire, and looking and acting even more casual than his clothes. He strides nonchalantly up to the mike, so laidback he’s the opposite of charismatic, and then just lets loose with lightning-fast, explosive guitar runs that had the entire bar breaking into applause.

Then their small, very thin saxophonist, a very young African-American man dressed in a vest, very neat clothes, and eyeglasses, looking like an honor student instead of a bluesman, starts walking all thorough the bar, playing the most slinky, sensuous, sax solos imaginable, stopping and swaying and playing right up against several of the bar patrons, to their delight.

That did it for me. I went up while they were playing and bought their self-titled CD, “Memphis Blues Masters,” and as I walked back to my chair the lead vocalist thanked me, and then absolutely made this whole trip down the blues trail a thing of glory and wonder for me by performing an exquisite rendition of Otis Redding’s “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay.” Dock of the Bay has always been my number-one anthem, the song of my soul, along with the Beatles, “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

I couldn’t have been happier at that moment, but then the lead singer sang Redding’s song so powerfully it made my joy all the greater.

Otis’s immortal song was his last hit single, released just after his death at a terribly young age in a plane crash, and his lyrics have always been a vital part of my philosophy of life.

Otis sings about leaving his home in Georgia to come all the way to the San Francisco Bay because he “had nothing to live for.” But even after traveling 2,000 miles from home, he finds that, “nothin’s gonna come my way.”

So now, the dock of the Bay is his only home. He’s homeless, and as he watches the tides roll away out into the vast distance of the ocean, he sings a line as blue as the waters: “This loneliness won’t leave me alone.” I love that line, sing it again: “This loneliness won’t leave me alone.”

Then, strangely enough, in the middle of this lamentation and this loneliness, he finds his liberation. He realizes he may not fit in anywhere, ever, but in his stark loneliness, he discovers his own freedom to be truly himself. He can’t slave away for others, or conform to what others want, or fit into society, and that seems like a lonely kind of abandonment.

Yet, Otis Redding’s song always brings me joy. The singer feels loneliness to the bottom of his soul, but when he realizes he doesn’t fit in anywhere, and never will, he understands he is completely free to be himself, and no one can order him around. He is free to wander and daydream and watch the tides roll away.

“Looks like nothing’s gonna change.

Everything still remains the same.

I can’t do what ten people tell me to do.

So I guess I’ll remain the same.”

The last two lines always seem like a triumph. “I can’t do what ten people tell me to do, so I guess I’ll remain the same.” It’s all about the freedom of the individual soul, a hard-won freedom found in the middle of alienation and aloneness.

To top off a perfect night on Beale Street, I opened the Memphis Blues Masters CD and found that it included “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay” on the list of songs!

‘We all will be received in Graceland’

When Ellen and I had first arrived in Memphis after 11 p.m., we’d already found that all the hotels and motels didn’t have any vacancies. We decided at the time just to enjoy ourselves anyway, but now it was 3 a.m., and that decision didn’t seem as brilliant as before.

We ended up driving down anonymous streets and freeways in the dark, bleary-eyed from lack of sleep, no idea where we were, no motel in sight, in a city our friends at Abe’s BBQ in Clarksdale had warned us was “dangerous at night.”

Finally, we saw a motel that had a quote from John Lennon on its main sign: “Before Elvis, there was nothing.” That felt like an omen. So, we entered the motel’s office and found a lavish, adoring shrine to Elvis, adorned with his memorabilia. The motel had one vacant room, and as we sank into exhausted sleep, I wondered why a motel in the middle of nowhere would have an Elvis theme.

When we woke up the next morning, we found out why. We had unknowingly ended up on Elvis Presley Boulevard, and, as unbelievable as it seemed, we were only one block away from Graceland!

Paul Simon’s song had been echoing in my mind the whole trip, and now it really resounded:

“I’ve reason to believe

We all will be received in Graceland.”

With this kind of providential sign, and the highest recommendation from the great people we’d met the night before at Abe’s in Clarksdale, we had to go pay our respects.

I’d never even wanted to see Graceland, but I’m so glad we visited. Presley bought the pretty mansion with white columns in part because he’d promised his parents they could live there, and in part to find a protective space from the pressures of celebrity.

It was nowhere near as lavish (let alone decadent) as I’d heard. To be sure, there were rooms with stained-glass peacocks and a baby grand piano, pool tables and chandeliers, and the so-called “Jungle Room” with a small, indoor waterfall. By today’s garish standards for celebrity homes, Graceland is not that remarkable.

But for music lovers, Graceland is something truly special. Videos about Presley’s musical accomplishments play on the tour, and there are displays showing his music awards. Graceland has an indefinable aura, a vibration, that makes one feel how historical and masterful Presley’s music was, how iconoclastic and vital.

Presley was one of the greatest singers of his generation, and he found so many ways to creatively re-interpret and intermingle all the kinds of Southern music he had loved growing up. Presley’s genius was to create this innovative integration of Gospel music, country, rhythm-and-blues, rockabilly, and the blues, and blend them all into something new and moving and spectacular.

When we toured the Memphis Rock and Soul museum later in the day, the exhibits there gave a very insightful look at how hard the poor white and black farmers and sharecroppers worked. It was the Depression and they were trapped in poverty, but these hardworking country people, black and white alike, played and mingled the blues, country music and gospel, and thereby brought to birth an incredibly creative musical legacy.

How interesting that Jimmie Rodgers, the long-ago father of country music, and Elvis Presley, the incomparable vocalist who cross-fertilized the blues, country and gospel into a potent mixture called rock and roll, both came from Mississippi.

Rodgers and Presley are two of the only white musicians who are respected and admired as blues singers by many blues musicians. Rodgers was born and raised in Meridian, Miss., and was a railroad worker who became known as the “Mississippi Blue Yodeler.” Presley was born into a poor family in Tupelo, Miss.

Once again on this trip, I felt amazement in contemplating Mississippi’s musical contributions to this nation.

While still back at Graceland, Ellen and I had walked down the long corridors filled on both sides with Elvis’s gold records and other musical awards. We were both hushed and somewhat in awe in this corridor that felt like a sacred shrine to the music that had changed our lives.

It was unexpectedly moving to see the gold records for “Jailhouse Rock,” “Heartbreak Hotel,” and “Don’t Be Cruel,” and it was nothing short of overwhelming to see the gold records stretch out so far ahead. The truck driver in Clarksdale the night before was right: Elvis had as long a line of awards for Gospel music as he did for Rock and Roll.

I’d heard Elvis sing Gospel before, of course, but I found it very powerful to see how many Gospel awards he had, and to realize that he’d begun recording Gospel at a very early stage in his career. And he continued loving this music his entire life.

Seeing all his Gospel records somehow prepared me to go outside and see the Meditation Garden where Elvis, his parents and grandmother are buried. A memorial flame shines brightly, and these words are inscribed nearby: “May This Flame reflect our never-ending respect and love for you. May it serve as a constant reminder to each of us of your eternal presence.”

I don’t want to get all supernatural and eerie about this, but I swear you can feel Elvis Presley’s spirit here. It moved me very profoundly, in a way I never would have expected. Maybe it’s because this Southern boy, this hometown hero, is loved so deeply by so many people in Memphis and Mississippi. Maybe all that love and adoration makes it feel as though Presley’s spirit is here in the air somehow.

Maybe, I thought, Elvis’s music made such a big impact on so many people, that he’s now the patron saint of Memphis or something. I know that sounds so strange, and I never expected to feel that, but Graceland did something for me.

The minute we concluded the tour, I almost ran to the gift store. I knew what I wanted. A box set of every Gospel song Presley recorded in his life has been newly remastered, so I bought that four-CD compilation, entitled “I Believe: The Gospel Masters.”

It is absolutely extraordinary. I’d heard a few of his Gospel records before, but it is amazing to really explore this box set and hear how brilliant a Gospel singer Elvis truly is.

I’ll always treasure his superlative, sensitive, heartfelt spirituals. And I’ll always believe. That’s the title of the first song on this beautiful set of music:

“I believe for every drop of rain that falls, a flower grows.

I believe that somewhere in the darkest night, a candle glows.

I believe for everyone who goes astray,

someone will come to show the way.”

I’ll always believe. And I have reason to believe we all will be received in Graceland.

A Portrait of America in Black, White and Blue

Looking back at our revelatory experiences on the Mississippi Blues Trail, I feel such gratitude for the blues musicians who brought so much beauty into a country that too often treated them as second-class citizens.

Right after our trip through Mississippi, Ellen and I also attended a retreat on Gandhian nonviolence given by Narayan Desai, hosted by nonviolent activists Jim and Shelley Douglass in Birmingham, Alabama.

And after the three-day Gandhi retreat, we toured the Birmingham Civil Rights Museum, and visited the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham where the four young women were killed in a racist bombing attack. We then visited the Montgomery memorial to 40 martyrs of the civil rights movement that has been created by the Southern Poverty Law Center, and we had a private tour of Martin Luther King’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where the Montgomery bus boycott was planned. Next month in Street Spirit, I will report on that visit.

All I will say right now is that the martyrs of the civil rights movement were on our minds just as much as the masters of blues music. The stories of the martyrs and the musicians cast a great deal of light on each other.

You cannot listen to blues music for long before you are confronted by the terrible and tragic history of racism, slavery, segregation and discrimination in America. You don’t often confront those issues in blues songs, because blues musicians don’t sing of these issues that often. Even though most documentary films on the blues begin with the cruel reality of the slave system, it comes up only very rarely in the songs.

But when you honestly reflect about this glorious legacy of soul-stirring music created on plantations where some of the poorest, most oppressed people led lives marked by involuntary servitude and racial discrimination, it becomes impossible not to feel sick at heart.

When you first enter the B.B. King Museum in Indianola, you see exhibits of the sharecroppers’ hard lives in the cotton fields, and your heart sinks just thinking of so many lives damaged and distorted by poor schools, inadequate health care, shabby housing, and an unjust economic system rigged against the poor.

It’s hard to confront the fact that your favorite musicians — and their families, and their friends, and hundreds of thousands of people now lost to history — grew up suffering under this unfair and inhumane system.

Above all, when you realize how truly brilliant this music is, and how profoundly it shaped the music of the world, it becomes impossible not to feel deeply ashamed that the music of the great blues masters wasn’t more widely respected in their native land. It is a disgrace that the blues is loved so deeply elsewhere, and ignored so thoroughly in its homeland.

When Sonny Boy Williamson and Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters and Son House toured Europe on the annual American Folk Blues Festivals in the 1960s, they received the highest respect and reverence from adoring audiences throughout Europe. And the greatest musicians of the British Invasion unfailingly cited these American blues musicians as their heroes, their highest source of inspiration, their favorite musicians of all.

The Rolling Stones refused to play on the television program Shindig unless their idol, Howlin’ Wolf also played. The Stones were at the height of their international fame, so their wish was granted. The five members of the Rolling Stones sat almost worshipfully at Howin’ Wolf’s feet when he sang, and Wolf was always grateful to the Stones for that. But that was the first and only time Howlin’ Wolf ever performed on American television.

And yet, Howlin’ Wolf was one of the most amazing blues musicians of our time. He had a wildly original vocal style, an exceptionally hard-rocking band, and a bunch of outstanding songs. When Sam Phillips, head of the legendary Sun Studio, heard Howlin’ Wolf sing for the very first time, he knew he was the single most brilliant vocalist he had ever heard.

‘The soul of man never dies’

Sam Philips famously said about Wolf’s music: “This is for me. This is where the soul of man never dies.” Phillips consistently called Howlin’ Wolf his greatest discovery of all — a remarkable level of praise. Why is it so remarkable? Because Sam Phillips and Sun Studio also discovered and recorded Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, B, B, King, Roy Orbison, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis. Phillips helped launch the careers of the most exceptional musicians in America, and yet he always said Howlin’ Wolf was the greatest of all.

Now, think for a moment about how many times you’ve seen Elvis, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison and Jerry Lee Lewis on television, on radio, in movies, and in the newspapers. But in his native country, Howlin’ Wolf — who was revered in England and Europe — was virtually never on television, never in movies and remains almost unheard by mainstream audiences to this day.

It is not usually a matter of individual racism that millions of people have somehow remained unaware of the exceptional talents of a Howin’ Wolf. But it is an outcome of a racially divided society that has discriminated against African Americans in so many fields of work, ignored or belittled their accomplishments, bypassed their brilliance.

It doesn’t have to be the intentional racism of an individual. Often, it is only the indirect effects of a racially divided society. But the damage done is just as real, just as severe, as if it were intentional. And, of course, sometimes it is very intentional.

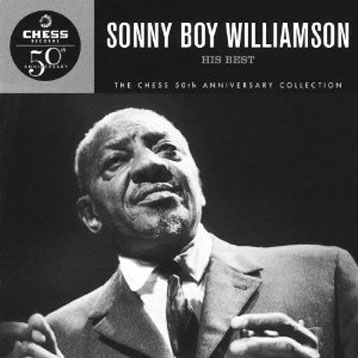

Sonny Boy Williamson was a great, legendary, blues musician, one of the very finest harp soloists and singers. When I was visiting the Memphis Music Store on Beale Street, Smokey Yates, the African-American “Bluesologist” who helped me, was a fountain of insight about the blues. He wrote his graduate paper in college about Son House and has plans to turn it into a book.

Smokey Yates loves Son House as much and more than I do, and unlike me, he saw House play in his heyday. He saw so many of the biggest blues musicians, back in the day when you could see them play in Memphis parks or on Beale Street for a couple bucks.

As I found out after talking to him for an hour, Yates has an encyclopedic knowledge of blues musicians and he works in a store with the single finest collection of Blues CDs I’ve ever seen. And who did Yates tell me he thought was the best blues musician of all? Sonny Boy Williamson.

But as brilliant as Sonny Boy Williamson was, he didn’t receive the acclaim he was due until he toured England and Europe as part of the American Folk Blues Festivals. In Europe, Williamson was lionized, treated as a musical genius by young rock musicians and blues fans there. He received ecstatic levels of praise and love and applause in England, and it moved him deeply because he’d never received the acclaim he deserved in his own country.

So Sonny Boy Williamson from Mississippi began dressing like an English gentleman, with a custom-made suit compete with umbrella and bowler hat, and an attaché case for his harmonicas. He loved England so much and he appreciated the way he was treated with respect there. So much so that when the other U.S. blues musicians returned home after the tour, Sonny Boy stayed in England for months, giving concerts all over the country to rapturous reception. He was making plans to move to England. Unfortunately, before he could do so, he died in 1965, while on a visit home to Mississippi.

Why did Sonny Boy fall in love with England and begin dressing like an English gentleman? Because they treated him like a gentleman there. He had to cross the Atlantic Ocean to find that level of respect and acceptance. And, of course, he found even more than that. He found that his music was wildly loved by countless white people in Europe, even while he was rarely heralded in his own land, the way he should have been.

Waters and Winter

I want to end this reflection on the blues with a somewhat more hopeful story. After all, as Eric Clapton said, “The blues is a music of hope and triumph over adversity.”

One story about Muddy Waters gives me hope for a better future. It’s appropriate that it’s about Muddy, because he was more than just a great musician who left the Mississippi Delta for Chicago and electrified the music of the entire world.

He was also a man of great dignity and pride. He was a generous and magnanimous man who helped so many musicians in his day, black and white.

In the 1950s, Muddy Waters created the finest electric blues band of all, and, in terms of the music scene in Chicago, Muddy was a king.

A few white kids named Paul Butterfield, Elvin Bishop and Mike Bloomfield wanted to play the blues, and when they showed they had great love for the music and a lot of talent, Muddy Waters was glad to share a stage with them. He could have seen them as competitors or even as white usurpers of his music, but instead he generously befriended them. And he did more than play music with them — he helped protect and defend them. Muddy carried a great deal of weight in some of the tough bars on Chicago’s south side. Showing the decency and generosity that moved him to help so many musicians in the course of his life, Muddy staunchly defended their right to play, and commanded everyone to leave them alone.

Bloomfield, Butterfield and Bishop went on to form the highly successful Paul Butterfield Blues Band. A few years later, when Muddy’s career was experiencing a lull, Bloomfield and Butterfield came through for him and worked with Muddy to create a very successful collaborative album entitled, “Fathers and Son,” a celebration of the Chicago blues. I love the thought behind that record’s title. It is so fitting and poignant because blues players like Muddy Waters, Little Walter and Howlin’ Wolf were the fathers handing down their beloved blues to the sons. And it symbolically shows that black and white people can play in the same band and become part of the same familty.

After a few more years went by, Muddy’s career went on a significant downturn in the mid-1970s. His albums weren’t selling, and his longtime relationship with Chess Records was severed. Things looked grim, but then Muddy was signed by Blue Sky records, and one of his biggest fans, Johnny Winter, the long-haired, albino, blues guitarist, was assigned to produce his next albums.

Muddy and Johnny worked together as closely as father and son, and produced four great albums in a row that won Grammy awards, sold well, restored Muddy Waters reputation to perhaps its highest level, and helped him finally be financially comfortable.

The first album that Waters and Winter worked on was “Hard Again” in 1977, an amazingly great comeback record that featured Muddy singing passionate vocals, Winters playing spectacular slide guitar, and longtime Muddy associates, James Cotton on harmonica and Pine Top Perkins on piano. The critics loved the album, it sold well, and it won a Grammy award in 1977.

But to me, it’s a story about karma and respect and redemption. Muddy Waters did so much to invent a form of electric blues that inspired so many people. Like Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters often was more well-loved in England than in his homeland.

In the early 1960s, when Waters was on top of the Chicago blues scene, this man who had lived in a tiny wooden cabin on a cotton plantation until he was 28, this man who worked for appallingly low wages of 22 cents an hour set by the white overseer, this man who had experienced a segregated society in Mississippi, this same man was unbelievably friendly and helpful and protective to Paul Butterfield and Mike Bloomfield, two white youth, when they came onto his turf.

Sometimes, we reap what we sow. Johnny Winters had been completely inspired by Black blues musicians, and especially by Muddy Waters. Growing up albino and cross-eyed and long-haired in Texas, Winter was an outsider himself.

When Muddy most needed help, Winter did a great job of producing his albums and playing guitar on them. The mood on the “Hard Again” record is exultant. Muddy never sang better and Johnny screams with delight as Muddy sings his classic, “Mannish Boy.”

It sounds, for all the world, like Muddy Waters has fatherly affection for Johnny Winter when he says, “Play it, Johnny!” He sounds for all the world just like a proud father, so pleased when Winter takes off on a blistering blues solo.

When Johnny Winter and Muddy Waters began touring with this well-received album, Muddy often introduced Johnny as “my adopted son.”

Fathers and sons. A tale of Black, White and Blue in America.

THE END