by Terry Messman

The diametrically opposed strategies of nonviolent resistance versus violent rebellion have seemingly always divided those building social-change movements. The age-old clash between these irreconcilable approaches has erupted anew into a matter of paramount concern for almost everyone involved in the Occupy movement.

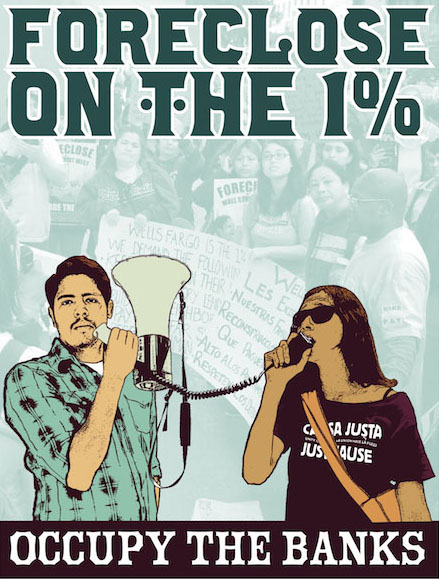

Occupy Wall Street has flowered into a nationwide movement that has done more to focus the eyes of the nation on the cruelties of poverty and economic inequality, than any movement since the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. Showing inspiring courage, vision and creativity, tens of thousands have joined Occupy’s daring attacks on the greed and corruption of Wall Street firms, big banks, and corporate capitalism.

Along with rebelling against the unjust domination of the wealthiest 1 percent, Occupy also has demonstrated a heartening level of solidarity and support for people struggling with poverty, homelessness, foreclosures and unemployment.

Yet, this young movement already finds itself at a crossroads. While many Occupy activists are deeply dedicated to the principles of nonviolent resistance, a large number have supported the “diversity of tactics” approach, and justified property destruction and physical attacks on the police and media reporters.

Everything is at stake for the Occupy movement: its future direction, its chances of success, its identity, and its very soul.

Many voices are offering counsel to the Occupy movement at this moment, and one of the most thoughtful is George Lakey, a longtime nonviolent activist and trainer who has just authored a fascinating account of how workers in Norway and Sweden created a nonviolent movement that successfully challenged the rule of the big banks and economic elite, and remade their country to serve the 99 percent. [See “How a Nonviolent Struggle by Workers and Farmers in Sweden and Norway Broke the Power of the 1 Percent” in the March issue of Street Spirit.]

Street Spirit interviewed George Lakey about the most productive way forward for this fledgling movement as it is pulled in conflicting directions between nonviolent resistance and the “diversity of tactics.” Although Lakey has been outspoken in his defense of the great potential of nonviolent movements, he has also advocated building a dialogue with those in Occupy who promote a diversity of tactics.

His long experience with social-change movements reaches back to his arrests during sit-ins in the civil rights movement. He was a trainer for Mississippi Summer, preparing nonviolent activists to go into a state sweltering with racism and oppression to nonviolently resist segregation.

A lifelong Quaker, Lakey joined with other Quakers to form A Quaker Action Group, which sailed a ship into Vietnam in 1967 that defied the will of the U.S. government in carrying medical supplies for the victims of U.S. bombings.

He taught at the Martin Luther King School for Social Change in Chester, Pa., and cofounded the Movement for a New Society, which trained activists across the nation in nonviolent organizing. As founding director of Training for Change, Lakey trained activists all over the world, including coal miners, homeless people, prisoners, Russian lesbians and gays, Sri Lankan monks, striking steel workers and South African activists.

He founded the Philadelphia Jobs with Peace Campaign, a coalition of labor, civil rights, poverty and peace groups, and was an architect of the Campaign to Stop the B-1 Bomber, which mobilized to gain cancellation of the B-1 in 1977.

A founder of Men Against Patriarchy, Lakey helped build the men’s anti-sexism movement of the mid-1970s. As an activist in the gay liberation movement, he was arrested for civil disobedience at the U.S. Supreme Court in protest when it upheld Georgia’s anti-gay statute.

Lakey is now very involved in environmental issues, working to alleviate the damage caused by mountain-top removal and organizing with Appalachian people to fight the hazards of coal mining.

Creating a lasting resource for movement activists, Lakey is guiding students at Swarthmore College in creating the Global Nonviolent Action Database, a huge online library of more than 500 global nonviolent campaigns from all around the world. [Visit its website at http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu]

Lakey has taught peace studies at Swarthmore and Haverford Colleges, Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania. At present, he is a visiting professor in Peace & Conflict Studies, at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania.

David Hartsough, a lifelong peace organizer who directed the Nonviolent Movement Building Program for the American Friends Service Committee and then co-founded both the Nonviolent Peaceforce and Peaceworkers, has known Lakey for decades. Hartsough and Lakey have taken part in many protests with the Occupy movement and have been very involved in the debates surrounding nonviolence and the “diversity of tactics.”

Hartsough said, “George Lakey is one of the foremost strategists for building effective and powerful nonviolent movements that I know in the world. And he walks his talk. He’s not just teaching activism — he’s doing it. He has a very skillful way of helping other people grow so they become stronger and more powerful activists themselves.”

Lakey is the father of three children, including two adopted children of mixed racial heritage, and also played the major parental role in raising his grandchildren.

Hartsough said, “George Lakey combines the personal and the political. He’s doing all this work of building nonviolent movements at home and internationally, and at the same time, he’s a very loving father and grandfather who is one of the most devoted parents I’ve ever seen in terms of spending time with his children.”

The Street Spirit Interview:

Street Spirit: I was just interviewing Erica Chenoweth, the author of Why Civil Resistance Works, and she said that your Global Nonviolent Action Database is perhaps the most wide-ranging and comprehensive effort to document nonviolent movements around the globe.

George Lakey: That’s right. We started four years ago to research and write the cases of nonviolent struggle all over the world. We’re now approaching 600 cases from over 190 countries. I’ve been teaching a research seminar here at Swarthmore so it’s mostly been done by Swarthmore students, but also with help from Georgetown University students and Tufts University students.

Spirit: Why is it important to document all these nonviolent campaigns?

Lakey: So we don’t have to reinvent every wheel. So that activists can go to this database if they want to change something. If they want to defend the rainforest, or defend anything, they can go to the database to find out how other people did it. The Global Nonviolent Action Database is a searchable database so people can search for environmental campaigns, for gender equality campaigns, human rights, economic justice campaigns, environmental justice, peace, democracy. We have many, many campaigns overthrowing dictators. These are neighborhood-level struggles all the way up to the national and international level, the Greenpeace cases and so on.

We also score these. We rate them by degree of success, so they can find cases which failed completely, and try to figure out what they did wrong, and other cases where they succeeded completely, and still other cases where there was some success, but not full success.

Spirit: Many believe nonviolent resistance can be effective in making minor reforms, say, on a neighborhood level, but they have great doubts that nonviolence can be successful against dictatorships or genocidal regimes. In your research, did you find nonviolent movements that challenged brutal regimes or powerfully entrenched military dictatorships?

Lakey: They have done it many times in history, and the reader can simply read them on the database, case after case after case. They can also read cases where people first tried to overthrow a dictatorship violently, failed, switched to nonviolence and succeeded. There was a very brutal dictatorship in the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos — very well established dictatorship. He was overthrown in 1986 by what was then called, by those people, “People Power,” and that introduced the phrase.

Also, I am fascinated by the twins, the pair, that happened in 1944 in El Salvador and Guatemala. Both of those dictatorships had been very well established, a decade or more. In El Salvador, they did try to overthrow Hernandez Martinez, the president of El Salvador who had ordered large massacres of thousands of peasants, censored the media, banned elections and violently repressed dissidents. First, they tried to overthrow Martinez with a military revolt. It failed, because he was still powerful enough to put down the violent rebellion. Then university students said, “Well, that didn’t work, so let’s try nonviolence.” And they led a nonviolent insurrection and overthrew Hernandez Martinez.

So next door in Guatemala, the students noticed this and they became envious of the accomplishment of the El Salvador students. Something like the Egyptians last year getting envious of the Tunisians and saying that if the Tunisians can do that, certainly we can, and some Egyptians considered themselves humiliated by the Tunisians and thought it was a matter of honor that they should overthrow their dictator, Mubarak, which they did.

So in Guatemala, in 1944, the students went up against Jorge Ubico, who was called the “iron dictator of the Caribbean” and they overthrew him nonviolently.

Spirit: Beautiful examples. That shows what I call “the chain reaction of conscience,” where one nonviolent movement can give others new insights, and inspire them to act for justice. That’s how movements spread like a good virus.

Lakey: Exactly right. In fact, on our website we have a button on the home page called “waves.” You can browse cases by looking at waves that you describe. So we have an African wave of pro-democracy cases in the early 1990s, the Asian wave in the late 1980s. We have, of course, the Arab Awakening, that’s a wave, and the U.S. civil-rights movement, which was a wave. We’re going to put in a Latin American wave.

Spirit: So in the history of these movements, you found that these things are transmitted from group to group, so one wave creates another in a circle of inspiration that renews itself.

Lakey: That’s right. This is not a new invention by Occupy; this is something people have been doing — waving — for quite a while.

Spirit: After studying the patterns of many nonviolent movements, both those that succeeded and those that failed, have you developed an insight into the typical stages that work in building successful nonviolent movements?

Lakey: Yes, yes. It seems very important to prepare for repression — that is, not to expect that somehow your own government will be different, or that it will be gentle, it will be nice. I run into this with the Occupy movement. Some people were shocked by repression. It’s very important to prepare people for the fact that the privileged will fight back for their position. So a period of preparation is extremely important in which people get to understand the nature of the thing they are going up against. Also, it helps a lot for success to be clear about what the vision is. It doesn’t have to be a blueprint, but a vision of what they want, instead of what they’ve got.

Spirit: Occupy has been criticized for refusing to agree on a vision that they can share with the public and supporters.

Lakey: That’s right and that’s a weakness in Occupy, which they can still remedy. Occupy is an infant movement. It’s like the civil rights movement in 1952 or something. It’s very, very infant and it has time to do a lot of work, but it would be good for it to know that it has that work to be done.

So one big thing that needs to be done is preparation for repression coming down the line. Another important thing is to solidify the organizational structure of the movement, because what holds people together under repression is solidarity — the links that people have, the bonding that they have, one with another. That’s particularly important in this country. In some countries, if you know enough about the culture of the country you are looking at, you know well they already have clan structure or they already have a traditional society and tremendous community.

Spirit: Other societies often have a greater sense of community than we do. And we don’t realize our lack of community until we try to build a movement.

Lakey: Exactly. So it’s very, very important here to be intentionally building community, building solidarity. So if one’s done that kind of preparation and training for actually going up against the repressive forces, the security forces of the country, then you can do small group interventions, small group confrontations that probe for weak spots in the status quo because there’s always weak spots and strong spots. And smart strategy is to not attack the strong spots but to attack the weak spots [laughs].

And you need to demonstrate that you’re winners, not losers, to the many people who are watching you with interest, but are not willing to commit yet. So there may be something very satisfying in a kind of martyr’s point of view to go up against the strongest thing and get completely walloped, that’s a very righteous thing to do, but it also does establish the profile of loser — and Americans are not the only people who don’t like losers. Very few people actually like losers.

We need to create campaigns in which one uses nonviolent direct action for winning achievable goals. And then coming out of that saying, “Look we won, join us, now we’re tackling this and you can help us do it.: That was the secret to success of the early civil rights movement that so many students were inspired by the college up the road that integrated their lunch counter and said, “Oh if they can do it, we can do it.” That’s also Egypt with regards to Tunisia. So the wave phenomenon is far more likely to happen if that’s done.

Gandhi knew this. After the failure of his first national effort to take on the British in 1919 and 1920, Gandhi realized: We’ve got a very despairing and hopeless sort of people here. We’ve got to do some locally based campaigns in which we win some things. So he helped industrial workers win strikes, he helped peasants win peasant struggles and he put the Indian people into fighting shape through successful local campaigns such that, then the next time out against the British, the major national convulsions known as the Salt Satyagraha movement, the people were able to send a very strong signal to Britain that its days were numbered.

Spirit: One of the most difficult tasks that can confront a nonviolent movement is challenging the economic elites, and trying to get economic justice. And, of course, that is one of the central aims of the Occupy movement. Have you come across any examples of nonviolent movements that successfully challenged the powerful economic elite?

Lakey: The two clearest examples are the cases of Sweden and Norway. It’s the most successful article I ever wrote, and it’s now gone viral. In Sweden and Norway, people’s movements took on the 1 percent and they defeated their political power. In both countries, troops were called out, and people were killed. In Norway, there was a plot to create a fascist state to replace the one they had in order to really crack down. The plan was to do the Mussolini or Hitler model. But that plot did not eventuate and in both cases the 1 percent had to retire from political dominance and the new leadership group got to be the workers and the farmers.

Spirit: What were the workers doing that led to government crackdowns where people were killed?

Lakey: Strikes. Strikes. They found that was their single most powerful weapon. But they also used boycotts and mass demonstrations and occupations. Which tactic turns out to be the most powerful depends on the context; but in the Norwegian and Swedish context, it was the strike that was the most powerful.

Spirit: When you say that they retired the 1 percent, and replaced them, what was the nature of the economic transformation they set in motion?

Lakey: They were able to set up a new society in which they could virtually eliminate poverty, get rid of slums, open higher education for free, make an assured secure retirement available to all, create a health care system second to none for everyone.

Norway is a very long country. It extends even north of the Arctic Circle. If you’re way at the north end of the country and you get a brain tumor that needs surgery that only somebody in the other end of the country can do — say, in the capital city of Oslo — the system itself flies you to that hospital to take care of your surgery. Universal daycare, universal this, universal that. They were able to establish all those things because the 1 percent no longer had the veto power that they had had previously.

Spirit: That’s exactly the economic transformation our system needs and it’s a central goal guiding the Occupy movement, and the homeless movements we’re involved in. Maybe what we need is to create time machines to pull in those knowledgeable activists from Norway and Sweden to show us how to do it.

Lakey: Well, they can start by reading our database.

Spirit: I knew that would give you an advertisement [laughs]. You’ve written that the conventional wisdom shared by the left, right and center is that violence is the most powerful political force of all. Why do you say this belief is as popular as the belief that the earth is flat, and just as incorrect?

Lakey: Because it doesn’t turn out to be true. Just as some brave people were willing to sail from Europe to the west and hope they wouldn’t fall off the edge of the earth and then it turned out that they didn’t, so also there have been some brave people who, despite conventional wisdom, went up against entrenched, violent dictatorships and overthrew them nonviolently, in situations where previous violent attempts had failed. So it’s obvious that violence, while it has some power, is simply not as powerful as nonviolence in these cases.

Spirit: You contend that people power is more powerful than military force. Again, that is counterintuitive for most people, who believe the exact opposite is true. After a lifetime of research and activism, what makes you believe that the unarmed power of the people can be a stronger force than military power?

Lakey: Let me tackle the other end of it. The reason why people believe that violence is more powerful than nonviolence is not accidental. That is the message that is taught to us by the 1 percent. In all societies in which people believe violence is more powerful than nonviolence, the 1 percent has messaged that, has drummed that into people’s consciousness as clearly as racism has been drummed into the consciousness of little girls and boys in the United States or South Africa. It’s the 1 percent that works very hard to convince us that violence is the most powerful thing.

So those in Occupy who want to be cynical about the intentions of the 1 percent might ask themselves: Why is it so important to the 1 percent that we believe that violence is more powerful? It’s so important because then they know they can beat us, because they are the ones who have the overwhelming instruments of violence. They can keep us in line as long as we believe that violence is the most powerful force. So it is this massive manipulation that is thousands of years old, maybe older than that, and it’s totally in alignment with the patriarchy.

Spirit: You’ve found that the success or failure of social-change movements often depends on who is most believable in charging the other side with instigating violence. Why is that so important?

Lakey: Because violence offends us. Violence is actually against human nature — it offends us. Start beating somebody up on any street and notice the reactions of the people walking down the street. The sight, the smell, the sound of violence is offensive. It violates our sensibility.

Spirit: Why do the authorities believe it is so important to not be labeled as violent and not be exposed in using police violence in defense of an unjust system?

Lakey: It delegitimizes them. What’s going on with Syria right now. The government of Syria has turned from a so-so state into, in the world’s estimation, a rogue state because of the use of violence. Violence discredits the purveyors of it.

Police have to work very hard to stay legitimate in our society because they often have to use violence, so they have a very hard time using violence and at the same time being regarded positively. Yet it’s very important for their work that they be viewed positively. So the state has to do all this tremendous work to keep their legitimacy going as the purveyors of violence. The same with the army, the same with the soldiers. Tremendous cultural effort goes into trying to maintain the legitimacy of violence. It’s very tough.

Also, training has to be very, very intense by the military to even get people to be willing to shoot their weapons in situations where they’re in danger. As late as the Korean War, there were many soldiers on battlefields not squeezing the trigger, or shooting overhead, rather than shooting the soldier on the other side.

So even though I understand that there are some people in the Occupy movement who are very attracted and intrigued by violence, I think they have a very, very partial view of the larger cultural significance of violence and how it’s been used and manipulated by the 1 percent.

Spirit: In the early days of Occupy Wall Street, the movement won a huge influx of public sympathy because people were outraged by the irresponsible violence of New York police. Now, in Oakland, the public has begun perceiving some of the protesters as violent and that seems to be eroding public support. Is that the kind of pattern that has lessened public support in other movements?

Lakey: Oh, yes. All the movements I can think of that we have in the database in which they won, that dynamic was at work. There are colleagues of mine who call this the “paradox of repression” because the repression is initiated by the state in order to defeat the movement and instead the movement grows. It’s what Gene Sharp called political jiu-jitsu.

Spirit: Police repression boomerangs on the state and delegitimizes it.

Lakey: Exactly. If anyone wants to see case after case after case of just that pattern, the database shows that. Sometimes, campaigns are on the skids, they’re just not getting much support, not much is happening, not much growth. It looks like the regime is very safe and then the regime makes the mistake of snatching some student and torturing them all night. The word gets out and suddenly there’s another 10,000 people in the street.

Spirit: That was certainly true with the civil rights movement, when completely nonviolent protesters were met with enormous violence from police. Just the shock of people seeing that violence really helped the movement grow, and the protesters’ courage in facing that violence also inspired support.

Lakey: Here’s another specific example. I write the case in the nonviolent database about the South Korean overthrow of a dictator in 1986-87. Students and young people were very involved in that campaign, but also pastors and professors and workers and some farmers as well. It’s an example of times when the movement wasn’t doing that great and then the government over-reacts.

So on June 9, 1987, a student was hit by a teargas bomb and fatally injured and the next day, a huge rally was organized which, in turn, led to a parade with a million people on June 26. So the student dying from that teargas fragment led to a million people brought into the streets. Actually this was the climax of that struggle, and one of the significant things was that it had basically been students and working-class people, but when that student died, the middle class joined the struggle.

One reason that is so important for Occupy is that the Occupy movement is about economics and it is about the working class being oppressed in this country by the 1 percent. A lot of the management work of oppressing working-class people in the U.S. is done by middle-class people, so middle-class people themselves are ambivalent in the U.S. political system. A part of them is leaning toward Occupy, especially the part of them who are losing job opportunities or whose jobs are insecure and who are wondering how they are ever going to pay the higher and higher tuitions. But a vast part of the middle class tends, decade after decade, to give the 1 percent the benefit of the doubt.

The people on top know this and they know that they’ve got to hold the middle-class people on their side, because 1 percent is not very many people. So the South Korean story of 1986-87, where the middle class as usual held back and then, with the workers and students out in front suffering terribly, and then the repression became naked and clear, and the middle-class people turned out and that was the end of the dictatorship.

Spirit: In the U.S., when the overwhelming violence of the segregation system was shown on television — with people being beat, shot, arrested, churches being bombed, little girls being killed — that pushed a lot of the middle class that had been sitting on the sidelines to support the civil rights movement.

Lakey: Exactly, exactly right.

Spirit: And before that happened, King and his followers were being blamed by the media and by the political powers in the South with fomenting violence.

Lakey: That’s right and I wrote an article describing that pattern on the Waging Nonviolence website called “Who’s Really Violent? Tips for Controlling the Narrative.” It’s very important to show the public who is really being violent. Especially when the movement is still young and only beginning to get its message out, politicians and the media will often succeed in blaming every appearance of violence on the protesters. Reversing this narrative in the public perception and exposing the system’s violent face of injustice is one of a growing movement’s most important challenges.

Spirit: Civil rights activists were portrayed as causing violence because their marches and sit-ins would lead to police repression. King had to show the public that the real violence was caused by those who supported the racist system of segregation. How did the movement switch this debate around so effectively?

Lakey: They did turn the debate around sufficiently to win, over and over. They didn’t win every battle, but they won a number of campaigns and they did it through heightening the contrast between their behavior and the security forces. One time when they didn’t succeed was in Albany, Georgia, where the local police chief defeated King and defeated the movement. He defeated them by having the police be very low key — only do the brutality in the jailhouses, out of reach of T.V. — but in public being very well behaved. So the contrast wasn’t heightened in Albany and the movement lost.

Spirit: In those places where the movement was successful, how did activists heighten the contrast between their nonviolence and the state’s violence?

Lakey: There’s a variety of ways of doing that. Andrew Young, one of the key workers with Martin Luther King, once explained it to a group of us here in Philly. He said, “You probably wondered why it is that when we do a march down to a point of confrontation, we’ll get the people down on their knees to pray. Well, you probably figured the pastors do that because they believe in divine intervention.” And Young said, “Yeah, sure, divine intervention’s a good idea, but the main reason we do that is because people down on their knees can’t run, and when the police come out with their nightsticks and start beating on people, people have a natural wish to run.”

But running does not heighten the contrast — he didn’t use that phrase, that’s my phrase. Running does not heighten the contrast between the activists and the purveyors of violence. The running, to a T.V. or a news photographer or a bystander, just looks like a riot and it gets reported in the news, that black people rioted on the streets of Birmingham, whatever. So sometimes you need to heighten the contrast in order to make your point, and if that means getting people on their knees so they won’t run, great.

A good example of the movement not understanding that was Chicago in 1968 in the Democratic National Convention, where demonstrators coming from all over the country were set upon by the police. They started to run away and the police chased them and bloodied them even in the lobby of the Hilton Hotel, where the police finally caught up with some of the demonstrators and beat them to a pulp inside the lobby on the expensive carpet. But the way it was covered in the media was: Activists Riot in Chicago. It took a national investigation to determine it was actually the police who rioted; it wasn’t the students who rioted. There’s no reason for Occupy people to make all of these same mistakes again.

Spirit: Something very similar to that occurred in Oakland. The police attacked marchers on January 28 and were terribly violent to them. But when they ran, and escaped through the YMCA, it looked to the public like they were at fault when they were just trying to escape the violence.

Lakey: Exactly. So white radicals need to learn from their black sisters and brothers in the civil rights movement.

Spirit: Civil rights activist James Bevel warned about how throwing bricks backfires and discredits the movement.

Lakey: Well, Jim Bevel said that one of those bricks might very well take the eye out of a police officer. If that happens, then the story about the demonstration is violence done against the police and the sympathy of the public goes to that police officer. No matter how many of us got beaten, the sympathy and the focus gets to be made on that brick and that police officer. So what that means is that whether you had a hundred or a thousand people standing up for their rights, their voices go unheard because the brick has a bigger impact than the voices of all those people.

So organizers have to ask themselves: who do we want to be heard? The people who are taking these risks and going out and facing the police — do we want their concerns to be expressed, do we want their struggle against racism or their struggle against poverty to get expressed? Or do we want that person who threw a brick to be the dominant part, the lead part of the story? So from Bevel’s point of view, it’s a tremendous disrespect to most people who come to a demonstration and are taking a risk, to take away their voice by giving the headline to the brick or bottle.

Spirit: One of the most effective ways the civil rights movement heightened the contrast occurred when polite students demonstrated peacefully, with great discipline, and the media showed incredibly brutal police attacking them anyway.

Lakey: Right. The Birmingham campaign wasn’t doing that great until Sheriff Bull Connor unleashed the hoses. But he wouldn’t have unleashed the hoses if the movement hadn’t kept persisting, persisting, persisting. Then the contrast between the water hoses and the often young people walking down the street in a highly peaceful and dignified way, singing songs and carrying their bibles, was a very effective example of heightening the contrast.

The Occupy movement has plenty of imaginative people and once they get the concept clear they can figure out a thousand ways to do it. We can use our imaginations once we get the concept clear. Don’t waste your time complaining about the media. Work with what is, and then use your imagination to be powerful. That’s what successful movements have always done. Pitiful, losing movements complain about mass media or they complain about the police beating them up. That’s the behavior of a loser and that will not inspire America to rise up against the 1 percent.

Spirit: The Occupy movement had enormous sympathy in Oakland after Scott Olsen and others were shot with gas canisters by the police and were very brutally mistreated. The movement was able to mobilize 20,000 people and shut down the Port of Oakland in November, then again in December — amazing achievements. But at the very tail end of otherwise nonviolent and successful protests, a few people begin throwing rocks at the police, starting fires, and trashing buildings. Given your research into these patterns in past movements, what effect does that have on the movement’s success?

Lakey: Well that reduces the contrast, doesn’t it? It reduces the contrast between the violence of the police and now the violence of protesters. And even though I don’t consider property violence to be violence, it’s read that way by many people who would like to be our allies.

In Philadelphia, in 2000, when the Republican National Convention came here, the movement activists started out with the high ground. We entered that convention in great shape and the police entered the convention in terrible shape in the eyes of the public — having just been caught on film doing horrible police brutality. And at the end of the Republican Convention, the activists looked like shit and the police looked great.

Spirit: What caused the reversal?

Lakey: What happened was that the contrast was turned around. The police chief, who is a very smart man who had learned a lot from Seattle in 1999, made sure that the police in the public eye were very restrained. On the movement side, we didn’t make sure our folks looked dignified and respectful of others. Instead, there was a lot of stopping of traffic, people desperate to get to daycare to pick up Johnny or Susan couldn’t do it because of huge traffic jams caused at random by people charging into the street with no strategic objective, no sense at all. Plus the property destruction stuff and vandalism.

So the police came out looking like heroes and we came out looking like losers. It was a tremendous reversal for the movement and it was because this concept of contrast was successfully used by the police. One of the reasons I stopped going to these large bashes of people gathered together, was because each of these large aggregations of people who come to the Republican Convention, the Democratic Convention, only set the movement back more.

Gandhi would be horrified to think that we should have our agenda set by where the power holders meet. What an acknowledgement of our powerlessness to say we have to go to where the power holders are and make a rumpus. Gandhi’s first principal strategy was be on the offensive, don’t be reactive. Be on the offensive and choose our own turf rather than running from place to place where power holders are meeting and trying to do a protest. It has very, very little utility in most cases. I’m truly hopeful that the Occupy movement wants to do something different, wants to have a learning curve and learn faster than the police about how to do effective nonviolent direct action campaigns.

Spirit: Poland’s Solidarity Movement originally committed property destruction in their strikes and occupations, but they learned that property destruction reduced their allies and also gave the police state justification to come down hard on them. What happened when they renounced property destruction and adhered more to a nonviolent mode of conflict?

Lakey: They grew, and the legitimacy of the state declined because the state was in a bind. How was it going to defeat solidarity without repression? So it had to do repression, but if it didn’t have the justification any more. If the authorities couldn’t use as justification Solidarity’s own use of property destruction, then their repressive violence was all the more naked and so they looked even worse. And that, of course, hurt them, so they end up losing the struggle and Solidarity won.

Spirit: What can today’s movements learn from that?

Lakey: That if we do stuff that justifies — in the eyes of the uncommitted — the repression of the state, we will certainly lose. And the uncommitted are, of course, most of the 99 percent. The Occupy movement is a very tiny part of the 99 percent. We need a lot more of those people. At present, they are not committed, they are watching with great interest and many of them are watching with great hope and we can win them over. But the only way to win them over is through strict adherence to nonviolent struggle.