“It’s criminal to be alive in this city and be poor,” a man known as Radical Rob declared this to an Associated Press reporter as he and some 30 others were evicted from Rainbow Village, a short-lived experimental community for unhoused people on the Berkeley waterfront. “I know the state could do better,” he said.

Rainbow Village stood for 13 months on a 27,000 square foot patch of ground previously used as a maintenance yard. Initially intended as a temporary solution to a localized housing crisis in West Berkeley, the village came to symbolize the hope of a humane response to homelessness that would prioritize the autonomy and dignity of unhoused communities themselves.

The community that would come to call itself Rainbow Village was born on a single block in West Berkeley’s industrial zone. In 1981, Vince Johnson began living out of his car on 5th Street between Cedar and Virginia. In mid-1984, others began to join him there. By 1985, about 40 people were living on 5th Street in cars, trucks, and buses in various states of operation and disrepair. Most of these new residents of 5th Street had become homeless for familiar reasons: lost jobs, problems with landlords, family disputes, health issues, drug and alcohol addiction.

But a number lived out of their cars for a different reason (or at least understood their condition in different terms). They saw themselves as living there out of a choice because they did not want to participate in “mainstream” American society. “There is more than one way to live,” explained one such resident. “I want the freedom to do what I want.” Many of these people identified with the Deadhead subculture, and a handful had recently traveled to Modoc National Forest for the annual hippie get-together known as the Rainbow Gathering. In reference to the gathering, some on 5th Street took to calling the block “Rainbow Village.” The name stuck.

The original Rainbow Village was notable as one of the first self-consciously organized houseless communities in the Bay Area. Residents held community meetings, took votes on issues when necessary, and made demands on the local government as a collective. “We are the only Berkeley homeless people who have organized as a group,” spokesman Harry Shorman explained when advocating for the installation of an outdoor toilet on the block.

But before long, homeowners and businesses in West Berkeley began to insist the city government expel the villagers and their vehicles. Although no major incidents occurred, a flurry of complaints about safety and quality of life issues soon spurred city officials into action.

At the same time that this community was establishing itself on 5th Street, a local election swept the progressive, social democratic third party Berkeley Citizens Action into government. Although it had already strayed from its more radical roots, BCA was the culmination of a long-term attempt to wield municipal power begun by participants in the social movements of the 1960s. Unlike many similar projects, BCA clung on through a series of disastrous election defeats, remaining a factor in local politics despite remaining a minority party on city council.

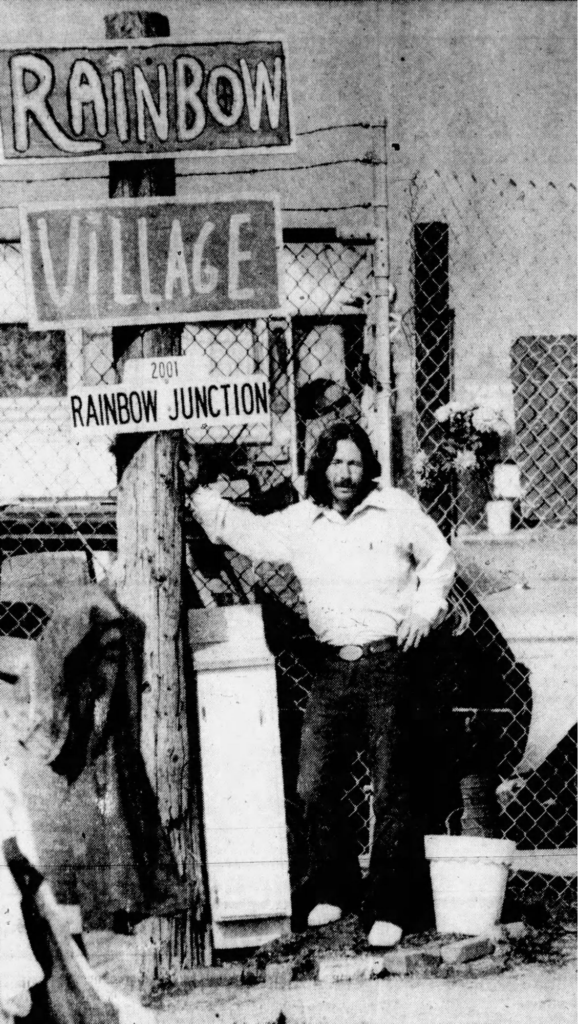

Rainbow Village spokesman Harry Shorman. (Ron Reisterer/Oakland Tribune, November 1, 1985)

In November 1984, a backlash against Reaganism finally propelled the BCA into an outright victory. They didn’t just win a majority, they won 8 of the 9 seats on Berkeley City Council. With the BCA supermajority on council and anti-imperialist socialist (and former comrade of Malcolm X) Gus Newport in the mayor’s office, Berkeley now had the most left-wing government in its history. The homeowners’ and businesses’ anger about the village on 5th Street presented the BCA with one of its first challenges: how would this government’s response to homelessness differ from its predecessors?

Rather than forcibly disband the community, the BCA offered Rainbow Village a new home: a patch of real estate on the waterfront. Like most of the Berkeley waterfront, this area (now part of McLaughlin State Park) had been used as a dump until 1983. While plans to turn the land into a park had already been settled, the project was still awaiting federal and state funds. The area the city offered the villagers was a vacant dirt lot then being used as an unofficial storage location for maintenance equipment. Residents would pay $30 a month and, other than some scant amenities provided by the city, manage the area themselves.

On January 31, 1985, the city organized a caravan to the new Rainbow Village. 37 adults made the journey; vehicles parked on 5th Street that were incapable of traveling the five blocks were towed to the new location at the city’s expense. Rainbow Village would be permitted to stay, city spokespeople announced, for up to two years. When conservatives, business interests, and other skeptics questioned the legality of the arrangement, the progressive city council simply declared homelessness an emergency and suspended the relevant laws (whether or not they had the authority to do this was far from certain).

On the waterfront, a “counter-culture mobile community” of about 50 people quickly flourished. Villager Robert Hamilton explained the community’s ethos: “If you got it, you share it.” The city installed multiple outdoor bathrooms and running water. The fire department brought over warning bells and equipment for an old-fashioned bucket brigade in case of fire. A steady stream of out-of-town Deadheads circulated through the village. Before the year was out, villagers had successfully lobbied for an official address: 2001 Rainbow Junction. This meant mail service, garbage collection, recycling. Many residents were able to access government assistance for the first time. While certain kinds of conflict were commonplace at Rainbow Village, the first eight months of the community’s existence saw no reports of major violence. To some of the residents, the most important thing the village offered was the chance to live free from the constant police harassment that still characterizes life on the streets.

Almost immediately, Rainbow Village faced fierce opposition. Its legality was challenged by multiple state agencies, including the State Lands Commission and the Bay Conservation & Development Commission, who were charged with managing the land and turning it into a public park. An arcane debate raged about precisely where city jurisdiction began and ended, based on the shifting of the shoreline with the tides. The owners of the nearby Marriott Inn and Marina Sports Center filed a lawsuit against the city over the village, which they argued the city lacked the authority to create. New temporary locations were sought out and debated.

Meanwhile, the village involved itself in other political debates around housing. In July, a representative of Rainbow Village spoke at a meeting of BART directors. The BCA-led city council was attempting to embark on an ambitious public housing plan which included a number of units on parking lots owned by the transit agency.

“Unless we go forward with public housing, Berkeley will only be made up of the rich,” BCA City Council Member Maudelle Shirek argued. The Rainbow Village representative urged BART to allow the construction. Villagers considered public housing and their own experiment to be two distinct, but complementary approaches to addressing the burgeoning housing crisis (the BART directors ultimately voted 6-1 against the public housing plan).

In August, Rainbow Village was rocked by a gruesome tragedy. While following the Grateful Dead on tour, two young Deadheads from the East Coast chose to stay in the community. They were beaten savagely and shot to death, their bodies dumped in the bay. Although few in the community believed the crime could have been committed by one of their own, Rainbow Villager Ralph International Thomas was quickly arrested and convicted of the murders. Although evidence of his guilt was strong, Thomas later won a new trial due to problems with his initial defense. He died before this second trial could take place.

While the press would frame the murders of Gregory Kniffin and Mary Regina Gioia as the point of no return for Rainbow Village, the city had already agreed to end the project in June, when it quietly settled its lawsuit with the Marriott. The imminent closure of the village was announced in January 1986. Some attempts were made to organize a response; Harry Shorman rode his motorcycle to Sacramento in a doomed attempt to negotiate a solution with state authorities. “What are they going to do?” one defiant villager asked, “Send in the cops and haul us out MOVE style?” Some advocated for a May Day rally of “bag-ladies” in protest. But in the end, there was no collective resistance to the looming displacement.

Rainbow Village was finally shut down by the city on March 2, 1986. The local government offered residents help finding new accommodations, but few requested it. One council member eulogized the project as a “valiant effort and a dismal failure.” Admitting defeat but remaining unapologetic, city official Hal Cronkite called the experiment “irresponsible and human,” adding, “It was just an experiment that failed. But I’d do it again if it were up to me. If nothing else, those folks got a halfway decent place to live for a year.”

The stakes were summed up quite differently by one resident who told the press that because of Rainbow Village, “I was able to go out and work because I had a residence, a place where I didn’t have to be woken up three times a night by the police. I had really cut down on my drinking for a long time. But what the hell. I’m gonna be back on the streets again soon. I don’t matter much no more.”

Matt Ray and Matthew Wranovics are the founders of Left in the Bay, a project that uncovers and retells stories of social struggle in the San Francisco Bay Area. Follow them on social media @leftinthebay.