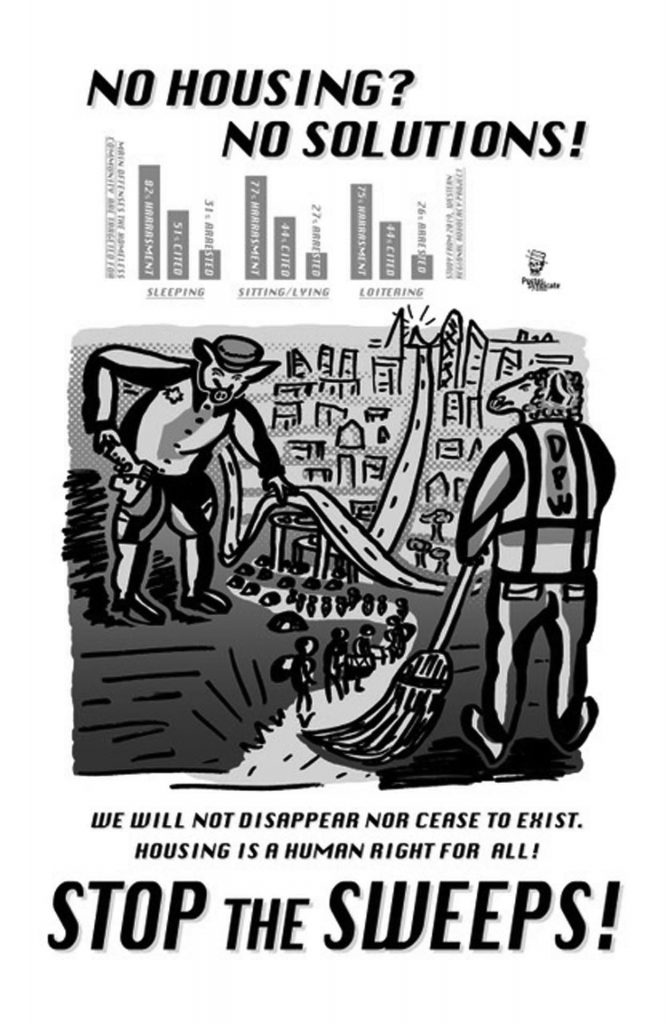

On November 16, around 7:00 am, Copwatchers arrived at the corner of Dwight and Shattuck to document City Manager’s Office staff, Public Works employees, and Berkeley Police Officers evicting an unhoused resident from the place they had been sleeping. Berkeley Copwatch has witnessed many such evictions of unhoused people along the Shattuck Corridor in the past weeks. This aligns with what we are hearing from houseless community members as well: that the City of Berkeley quietly decided to crack down on enforcement of sit/lie laws that largely sat dormant in the municipal code during the coronavirus pandemic. Over the last several weeks, numerous people living in tents along Shattuck and adjacent streets have been given Public Notices by the City citing violations of two “Shared Sidewalk” policies: BMC 14.48.120, “Obstruction of Streets/ Sidewalk,” and BMC 14.48.020 “Temporary Non-Commercial Objects.” These municipal codes, along with others such as the “3×3 rule” and “no sleeping/lying in public spaces,” make up the web of city ordinances that effectively prohibit people without shelter from existing in public spaces. While the ordinances may not be new, unhoused Berkeley residents are currently experiencing an unspoken change in policy that is drastically impacting their lives.

An anonymous source told Street Spirit that a member of the Berkeley Public Works Department said the new wave of enforcement is part of a new encampment management strategy by the City of Berkeley. We have reached out to the city for comment on this, and at the time of publication had not received a reply.

One resident described how BMC 14.48.020 prevented them from attending school for fear of having their belongings disposed of by the city while they were in class. Another resident holds a full-time job and must therefore leave their tent unattended for hours at a time, risking returning home to nothing. These are just a few of the ways in which the city’s municipal codes create impassable obstacles for people attempting to improve their living conditions or simply sustain themselves.

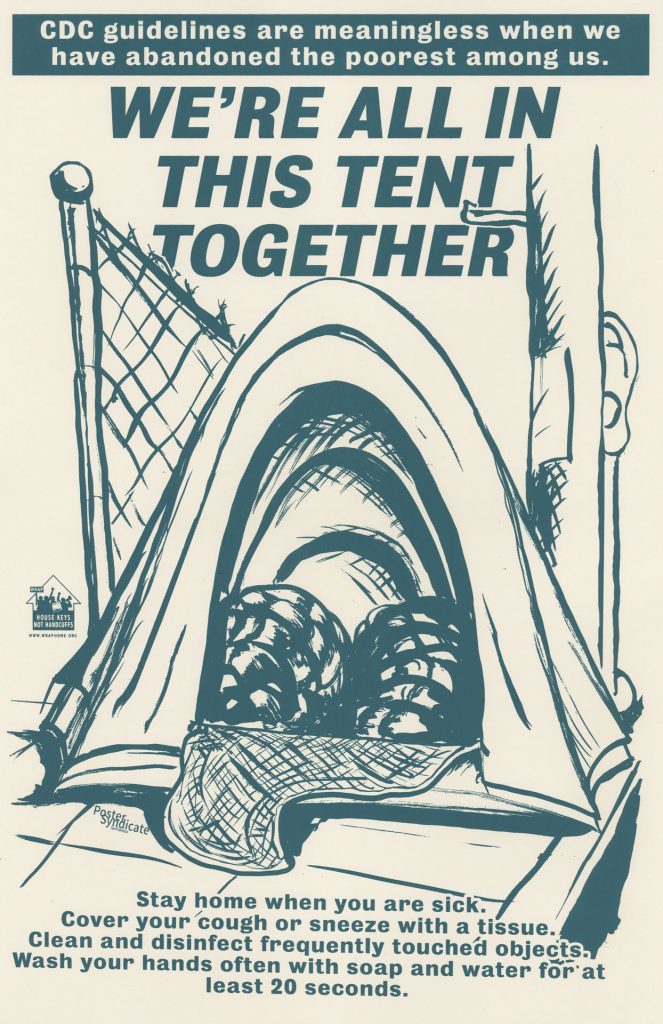

During the enforcement evictions, residents often ask: Where can I camp if I can’t camp here? Consistently, city staff and outreach workers say that they do not know. When it comes down to it, most displaced residents just end up moving around the corner. One individual, who has lived in a tent on Blake Street near Shattuck Avenue for over a year, said they feel “pushed” into the Horizon Transitional Village shelter on Grayson Street. The message from city staff is clear: the only place residents will not face enforcement is in a shelter.

Aside from the looming fact that there are not enough shelter beds for all the unhoused people in Berkeley, many are not interested when openings come up. Speaking with individuals recently evicted on Shattuck in prior weeks, they explained some of the reasons they would rather be in their tent than in the shelter:

“[In the shelter] you have no privacy, where everything is clicking off a concrete floor. Where there are no boundaries or acceptance or being able to be yourself. You have to have staff with you. You go into your house and you have staff with you 24/7 and you see how that feels.”

Another resident described how they were abused at a shelter years ago, and had since been offered a place where they know some of the same residents and staff will be present, making it an unsafe environment for them. One individual puts it plainly: “I’m not voluntarily putting myself back into an institutionalized setting.” It is clear that for a variety of reasons, often including mental health and physical disabilities, Berkeley shelters do not feel accessible to residents living on the streets, where they have a stronger sense of autonomy. If people cannot realistically expect improved living conditions in Berkeley’s shelters, then the only incentive to enter a shelter is threat of arrest or constant evictions by the city for violations of municipal codes.

In the face of harsh living conditions on the street, most people develop relationships of care with their nearby unhoused and housed neighbors. This is another reason why the city’s constant displacement of tent communities has such a harmful impact; beyond the physical displacement from their spot, it disrupts relationships of care, friendship, and mutual aid amongst residents. Dignity and honesty are deeply valued in these relationships, two things residents often say that the city’s response is lacking.

If the city of Berkeley cannot honestly provide its unhoused residents a more dignified and accessible place to live, where their networks of support are not severed, then it is both cruel and unusual for the city to put unhoused residents through the trauma of cyclical evictions.

Get active. Be aware. Refuse to be abused.

Berkeley Copwatch is an all-volunteer organization with the goal to reduce police violence through direct observation and holding police accountable for their actions. Formed in 1990, they seek to educate the public about their rights, police conduct in the Berkeley community and issues related to the role of police in our society at large. For more information visit www.berkeleycopwatch.org.