Amanda Nguyen, an unhoused resident of the encampment at High Street and Alameda Street in East Oakland, has not seen a United Service Company employee clean any of the porta-potties in the camp for the past four months.

“There are human feces smeared across the wall in the far-right bathroom,” Nguyen said. She pointed to another porta-potty where excrement piled up to the toilet seat.

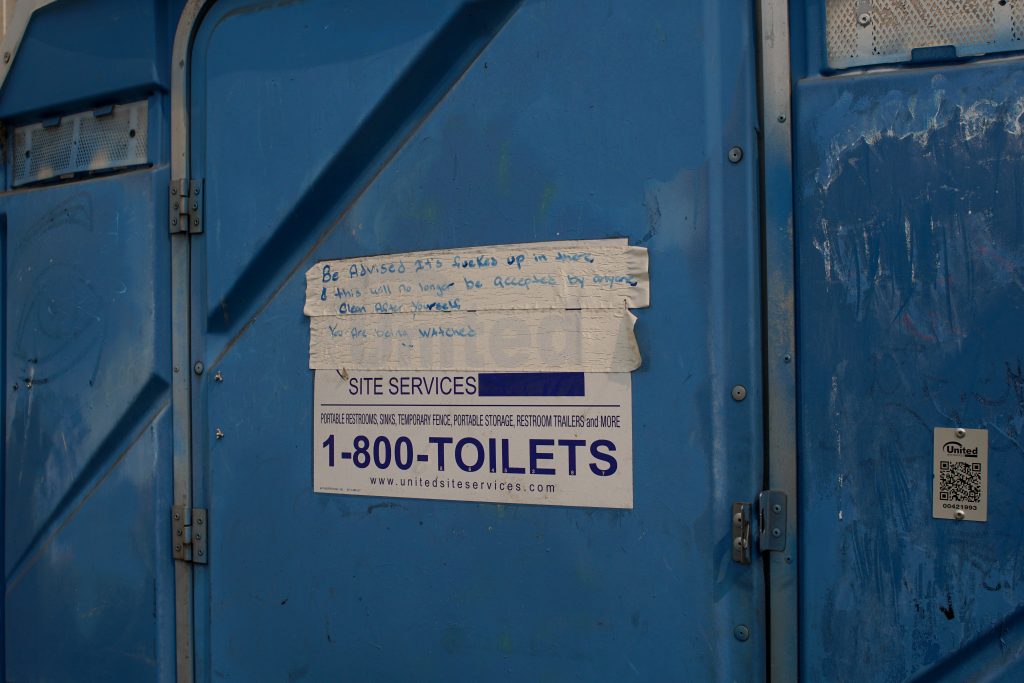

Nguyen has been regularly employed by the Baines Security Company, a group hired by residents to take care of security for the High Street camp. In that time, records within the porta-potties indicate that United Services has serviced the facilities once every two days.

“They have not come to clean the porta-potties once. They come here seldomly and when they do, they mark the cleaning sheet and leave,” Nguyen remarked from the inside of her car. “They’re scared to come in here and I can’t blame them. The porta-potty in the back is used by someone who has COVID-19.”

Prior to March 2020 and the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, there were 38 locations at which the City of Oakland had placed two or more porta-potties. Since then, the city has increased the number to 46 with each site including a hand-washing station.

There are at least 11 other porta-potties in Oakland that are paid for by community members. The Village in Oakland—a non-profit Oakland advocacy group—is currently paying for 10 portable toilets in nine different encampments. This is common in cities across the Bay Area—where there is a gap in sanitation services, non-profits and individuals step in to fill the gap.

Between December 8 and 11, Street Spirit visited all 46 porta-potty sites paid for by the City and found 30 were clean and stocked with toilet paper. 16 were found without toilet paper and filled with excrement. However, all 46 sites have recorded ledgers that state they are serviced every two days with toilet paper and hand sanitizer being replenished. But some may go for weeks without a standard cleaning.

The cities of Berkeley and Oakland both work directly with United Site Services, the leading provider of porta-potty rentals in the United States according to their website. However, servicing by United workers is not always reliable.

“The facilities are extremely difficult to manage,” said an anonymous source at the City of Oakland. “There seems to always be issues with the vendor. When the wildfires up North happened in August and September, four drivers had to stop servicing their routes.”

In addition to inconsistent servicing, workers are not forced to clean facilities if the porta-potty is found breaking their guidelines. This could mean that there are objects found in the toilet, the floor, or urinal other than excrement. And since workers are not required to inform local users as to why the facility was not serviced, weeks can then go by with no access.

Oakland’s Department of Health and Human Services has two paid employees who oversee the deployment of sanitation stations and the cleanliness of each site. Before November 2020, only one city worker was in charge of overseeing the deployment and upkeep of every site. That worker was not always able to visit every site and check to make sure United Services was fulfilling their contract due to other city obligations, says a staff worker at the Human Services Department.

With two paid employees, more porta-potties are routinely checked but there are still gaps. The Health and Human Services Department is also in charge of other services such as food distribution, which can take time away from routine site inspection, says a staff worker at the Human Services Department.

If city workers find a site is not being serviced, they reach out to the vendor as well as the community to determine what is causing the issue.

When asked if The Village in Oakland has this problem, Founder Needa Bee said sometimes—but at the end of the day it comes down to communication. “Part of the deal is, as the service provider paying for it, having good communication with the residents using the porta-potty and the porta-potty company.” Bee says a common problem they face is running out of toilet paper, so she spends time on the phone with the providers ensuring that more will be delivered. She also says that many of the porta-potties paid for by The Village have locks. She gives the key to encampment residents, who are charged with holding each other accountable for keeping things clean.

Shorty, an unhoused person living under the West Oakland BART Station, says he sees a United Worker come to service the nearby sanitation station by twice a week. Whether they service and clean the facility is another question.

“I spend 20 to 30 hours a week sweeping the street around the porta-potties,” said Shorty, who has been living curbside on and off for the past three years. “But people who don’t live here come in and leave [the bathrooms] dirty.”

Derek Suu, the community leader at the 77th Rangers in East Oakland, has had mostly positive interactions with United Services without having to use keys.

“The porta-potties are serviced every two days and we make sure to keep them clean,” Suu said.

The 77th Rangers currently have around 10 residents but have had up 60 in previous years. And according to the new Encampment Management Policy, their camp will be allowed to remain in place. However, some of the encampments at which the city currently provides porta-potty services are on the chopping block come January 1. It is not clear whether these

toilets will remain in place or be removed as the new policy is enforced.

Nevertheless, not all of the city-sanctioned por- ta-potties are located at organized communities. Some are placed at random intersections, blocks away from large gathering points for the homeless.

For the unsheltered people who live far away from the nearest porta-potty—or who live near one that has not been serviced for months—the only remaining op- tion is to relieve themselves in public space, amongst foliage or behind buildings.

“I refuse to use those bathrooms,” James Bixter, known as Monster, said.

Bixter and Baby Girl, his eight-year-old dog, have called the underpass below Berkeley’s University Avenue home for over five years now. The encampment, known colloquially as Seabreeze, encompasses both the underpass to the east and the large offramp on the west side of the freeway.

While the encampment hosts over 50 people at any time, the City of Berkeley has never placed a porta-potty or handwashing station there. Instead, local non-profits like the Berkeley Free Clinic have fulfilled this need by supplying the area with handmade wash- ing stations. Even then, Bixter is cautious about using the facilities.

“I rather go behind a bush…the bathrooms never seem to have toilet paper and there is never any hand sanitizer at the sink,” Bixter said.

At Point Isabel in Richmond, conditions are similar—the on-site porta-potties have not been serviced since September. Issues include a constant lack of toilet paper, little if any soap in the dispenser, and no running water.

“The bathrooms are so bad we walk to the end of the street where the park bathrooms are always open and clean,” Brenda Navarro said.

Navarro, who lives with her husband Hector, has been living out of their Honda Minivan at Point Isabel in Richmond for the past year. Originally used as a rest-point for truckers, the one-way road parallel to the San Francisco Bike Trail has exploded with homeless community members in the past six months.

“There used to be four RV campers parked along the road, now there are over 30 and only two porta-potties for everyone,” Navarro said.

Many community members including Brenda now frequent the East Bay Regional Park bathrooms located at the end of the street.

With the help of local non-profits, Brenda and other community members are trying to change that through weekly Friday meetings. But making any coordinated change is an uphill battle, due to over half of the community not attending meetings and strong opposition from local businesses located across the street.

“We want to have our own bathrooms so we can keep ourselves clean,” Navarro said. “We look like this because we don’t have access… it’s not fair.”