by Jess Clarke

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]roken windows policing is a theory of law enforcement that concentrates on arresting people for low-level offenses such as loitering, vagrancy, sitting on sidewalks, sleeping on the streets, and littering, in order to create an atmosphere of propriety and order for residents and workers in business districts and downtown areas of cities.

Its original proponent was George Kelling, co-author of a 1982 article in the Atlantic where he laid out the case using a real-estate metaphor to provide justification for discriminatory law enforcement, directed at poor and homeless people and aimed at “quality of life” crimes.

Kelling wrote: “One unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing…. If a window in a building is broken and is left unrepaired, all the rest of the windows will soon be broken.”

Using metaphorical reasoning and a series of anecdotes from Newark and Chicago, but backed up by almost no empirical evidence, Kelling comes to the conclusion that: “Serious street crime flourishes in areas in which disorderly behavior goes unchecked.”

Kelling spins a tale of the good old days when the police enforced community standards of middle-class respectability and all was right with the world. But beneath the surface rhetoric and the metaphorical reasoning, he isn’t all that shy about spelling out the real purposes — and targets — of this policing strategy that has been used against Blacks, Okies, homeless and disabled persons, and other undesirables.

“[T]he police in this earlier period assisted in that reassertion of authority by acting, sometimes violently, on behalf of the community. Young toughs were roughed up, people were arrested ‘on suspicion’ or for vagrancy, and prostitutes and petty thieves were routed. ‘Rights’ were something enjoyed by decent folk…”

Even at its origins, Kelling was well aware of who the victims of selective enforcement would be, but he frankly states that he just doesn’t care: “Arresting a single drunk or a single vagrant who has harmed no identifiable person seems unjust, and in a sense it is….”

He also acknowledges that his policy could easily result in lending the force of arms to the enforcement of prejudice.

Kelling writes:

“The concern about equity is more serious. We might agree that certain behavior makes one person more undesirable than another but how do we ensure that age or skin color or national origin or harmless mannerisms will not also become the basis for distinguishing the undesirable from the desirable? How do we ensure, in short, that the police do not become the agents of neighborhood bigotry?”

His only answer to this very significant danger is to hold out the faint hope that somehow the selection and training of good police can make up for bad policy.

“We can offer no wholly satisfactory answer to this important question. We are not confident that there is a satisfactory answer except to hope that by their selection, training, and supervision, the police will be inculcated with a clear sense of the outer limit of their discretionary authority. That limit, roughly, is this — the police exist to help regulate behavior, not to maintain the racial or ethnic purity of a neighborhood.”

It seems a very slim hope indeed that police will always remember, without fail, “the outer limit of their discretionary authority” while conducting police raids and street crackdowns.

Even in 1982, Kelling was concerned that the citizenry, and even the police brass, might not think that pouring police resources into driving “undesirables” out of a neighborhood would garner sufficient taxpayer support. His suggested solution was the use of private security forces. “One way to stretch limited police resources,” he wrote, is to “hire off-duty police officers for patrol work in their buildings.”

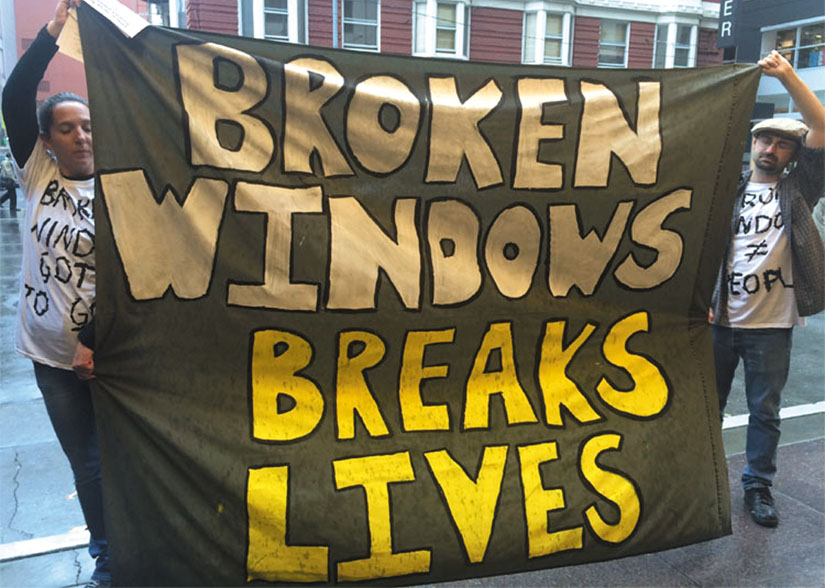

Broken windows policing is losing public support across the country and popular uprisings are bringing police under ever greater scrutiny.

So here we are today, when police hired by Business Improvement Districts and other property owners are on the front lines of a policing strategy that, by its original design, was premised on getting back to the good old days when “rights” were something enjoyed by “decent folk” — not by undesirable such as ourselves.

Listen to a Street Spirit Podcast of WRAP’s panel discussion about the connections between Broken Windows Policing and Business Improvement Districts.

http://www.thestreetspirit.net/brokenwindows/