by Steve Pleich

“Oh, a storm is threat’ning

My very life today

If I don’t get some shelter

Oh yeah, I’m gonna fade away.”

— Mick Jagger-Keith Richards

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]eginning at the federal level and affecting almost every effort to support people experiencing homelessness, the “housing first” model has become the mantra for the new “best practices” approach to creating positive outcomes for the homeless community.

Notwithstanding my belief that the best practices approach is simply lazy arithmetic when applied to a homeless population that is widely divergent in so many respects, I have serious questions about whether “housing first” is the best, most practicable option. I think it is not and I’ll tell you why.

In Santa Cruz, we have an institutional group wrestling with a best practices-based program called “Smart Solutions” to homelessness. This group, which includes civic leaders, faith community members, local homeless services agency representatives and large nonprofit public benefit organization stakeholders, is advocating for a “housing first” model as an answer to the challenge of sheltering our many unhoused residents.

However, in my view, this approach is impractical in that it all but ignores the present reality of our local housing market and, worst of all, is seemingly heedless to the size, character and complexity of our local homeless community.

According to the 2013 Homeless Census and Survey, there are approximately 3,500 men, women and children unsheltered in Santa Cruz County every night. As an aside, that number is openly acknowledged by the census takers themselves to be underestimated by as much as 50 percent!

Yet, in the entire county there are fewer than 700 emergency shelter beds available — and of these, less than 200 can be accurately described as “emergency” short-term shelter spaces.

In this landscape, advocating for housing first while ignoring the vast, crushing need for simple, safe shelter space is like advocating for a “rehabilitation first” model for those suffering from drug addiction in the absence of any existing programs for that purpose.

Simply leaving the most vulnerable to their own devices is not only foolish as policy, it is inhumane in practice. And it is not just advocates like myself who are giving voice to this systemic problem. Homeless people themselves have been consistently vocal on the issue.

Every Monday night, Calvary Episcopal Church in Santa Cruz, known by all as the “Red Church,” hosts a coffeehouse and meal for between 125 and 200 members of our local homeless community. I help out as a server and we often speak of the need for shelter and the lack of real housing.

One comment I hear often is: “I’ve been on the waiting list for Section 8 housing for months and don’t know if I’ll ever get housing.”

Another comment: “Even if I get my voucher, landlords in Santa Cruz don’t want to rent to a person like me.”

And another: “Housing? You’ve got to be kidding. I’m just trying to find some shelter at night.”

And one more: “All the money they say they are spending on housing. What about some shelter space?”

These comments are not in the least unusual and reflect the frustration that permeates the homeless experience in this regard. Yet the glaring lack of safe, available, nightly shelter receives scant consideration when “smart solutions” are so singularly focused on a “housing first” model.

And here let me draw the critical distinction between “shelter” and “housing.” Even the most ambitious housing programs, such as the 100,000 Homes Campaign, can only hope to successfully house even a fraction of our HUD-defined chronically homeless population.

In Santa Cruz, the local campaign partner, 180/180, has housed 200 individuals during the past two-and-a-half years. A fine thing, but what of the other 95 percent of people experiencing homelessness who don’t even qualify for such a program and yet have a continuing, nightly need for safe shelter?

Here’s my point. The finite financial resources available to programs created to shelter people experiencing homelessness are almost entirely being devoted to “housing” them. Where are the programs that build shelter space capacity to accommodate the vast majority of our homeless population? Where are the year-round “walk-up” shelters? Where are the armory-style shelters? Where are the designated family shelters? Where are the Safe Spaces Recreational Vehicle Parking Programs for the vehicularly housed? Where are the Sanctuary-style villages that could provide transitional shelter for those needing a temporary starting point for re-entry into the employment market?

These options are being ignored, or at the very least discounted out of hand. And this is precisely why “housing first” models are structurally unsound. They do not, and cannot, differentiate between the varied and distinct needs of individual groups within the homeless community.

Not every person experiencing homelessness wants to be “housed.” Many would welcome a safe shelter space but are not prepared to assume the responsibility that housing imposes. And here I hasten to add that the overarching preference for a housing first model is not borne of statutory or resource restriction, but rather is solely driven by political will. Indeed, existing law favors the establishment of a “shelter” first model.

Senate Bill 2 is a California statute enacted in 2008 that provides for designated zoning for emergency shelters. But more than that, it provides that any property or site in a community may be so designated if there is “insufficient shelter space” for the total number of people experiencing homelessness in that community.

In Santa Cruz and Santa Cruz County, that means that walk-up or armory-style emergency shelters can be established anywhere in the city or county without government approval because (and here’s where the arithmetic is not lazy), we have less than 700 emergency shelter beds to serve a population of 3,500.

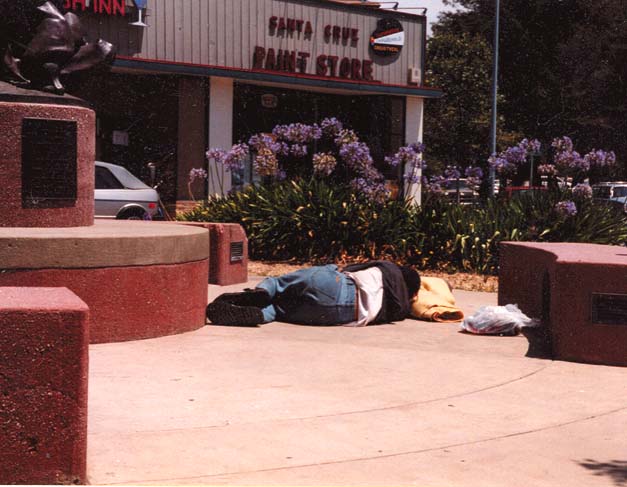

In our homeless community, there is a “storm threatening their very lives” every day. And although many members of mainstream society wish they would simply “fade away,” we must not waiver in the humanitarian effort to recognize their presence and support their needs.

There are many men and women of good will who believe that a “housing first” model is the best hope for doing just that and my words here should not be taken to demean those good-faith efforts.

But in our national rush to house we must not abandon the vision of creating safe shelter space as a fundamental part of a holistic approach to creating positive outcomes for people experiencing homelessness.

Steve Pleich is an advocate with the Santa Cruz Homeless Persons Advocacy Project.