Interview by Terry Messman

Spirit: David, when were you hired as staff organizer for the American Friends Service Committee in San Francisco?

Hartsough: I was hired in 1973 to be part of the Simple Living Program. My wife Jan and I shared the staff position. Then I began the AFSC Nonviolent Movement Building Program in 1982.

Spirit: As an AFSC staff, how did you become involved in the massive protests at the Diablo Canyon nuclear reactor in the late 1970s and early 1980s?

Hartsough: In the Simple Living Program, we were concerned that nuclear power was promoted as a way to have endless consumerism and endless energy.

Spirit: Consumerism fueled by radioactive plutonium.

Hartsough: Yes, without any thought of an environmental future for our world. So when the Mothers for Peace in San Luis Obispo came to the American Friends Service Committee around 1976, they were struggling to stop this nuclear power plant being built in their backyard. They had tried everything legally possible to stop it and the government didn’t care.

So they asked if we could help build a nonviolent movement to try to stop the Diablo Canyon Power Plant from going into operation. Our AFSC Simple Living Program decided we would support their struggle and help them build a statewide movement to stop that plant.

About 30 different groups from all over the state formed Abalone Alliance to stop nuclear power and the Diablo Canyon reactor, and to promote alternative energy.

We had about 100 people trained as nonviolent trainers, and AFSC played an important role in helping build that movement. AFSC published “Decision at Diablo Canyon,” a very well-researched booklet about the dangers of the Diablo Canyon plant being built on an earthquake fault. AFSC also put together the nonviolence training manual.

The movement was also successful in stopping the nuclear plant up in Humboldt County, and the Rancho Seco plant near Sacramento.

The Abalone Alliance

Spirit: Were you arrested for civil disobedience during Abalone Alliance’s campaign to shut down Diablo Canyon?

Hartsough: Yes, in 1977 and again in 1978, I was arrested. The first year, in 1977, there were 47 people arrested, and the next year, more than 470 were arrested. We’d multiplied our numbers by 10 times. And then, in 1981, when the license was finally granted, nearly 2,000 people were arrested at Diablo Canyon.

In 1981, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission said this was the safest nuclear reactor in the world as it gave its approval for Diablo Canyon to go into operation. And here were hundreds and hundreds of us sitting in jail down at Diablo Canyon feeling we’ve done everything we can, and what more can we do?

Then somebody threw a newspaper over the fence of our exercise area at the jail, and one of the engineers at the plant had gone public that the blueprints for the seismic support for the cooling systems of one of the reactors had all been put on backwards.

So it took Pacific Gas and Electric another couple years to retrofit all of that and they had to spend another couple billion dollars before it could go into operation. That plant — built with the cooling systems in one of the reactors totally wrong and totally unsafe — is what the Nuclear Regulatory Commission called the safest nuclear reactor in the world!

So we were not successful in stopping that plant, but I think our resistance at Diablo Canyon and the resistance at Seabrook, where AFSC also played a very important role, and Three Mile Island, where Quakers were very involved, helped send a message to our government so that no new nuclear reactors were licensed in the United States for about 30 years. And California passed a proposition saying no more nuclear power plants until they found a safe way to store nuclear waste — which they’ve never found.

Spirit: Abalone Alliance not only raised public consciousness about the dangers of nuclear power, it also educated people about how to build nonviolent movements. The actions at Diablo Canyon helped build an anti-nuclear movement that went on to organize opposition to nuclear weapons at Livermore Laboratory.

Hartsough: Yes, all these actions raised a lot of public consciousness. All of that grew out of this movement. And many, many of the people that were involved in the Diablo Canyon struggle have continued to be involved in the movement ever since.

Blocking the Holocaust Laboratory at Livermore

Spirit: A large number of Abalone Alliance activists went on to help spark the Livermore Action Group in the Bay Area. Why did you decide to become involved in the Livermore protests?

Hartsough: Nuclear power and nuclear weapons are very connected. It seemed to be a very logical next step in the struggle. Dr. John Gofman, who had been the head of biomedical research at Livermore Laboratory, was one of our speakers at our rally in San Luis Obispo against Diablo Canyon.

Gofman made that connection between nuclear power and nuclear weapons, and how dangerous nuclear power was. And I had been involved in the struggle for nuclear disarmament and the efforts to try to stop nuclear testing for all of my life.

Spirit: Beginning at age 14 when you protested the Nike missile plant.

Hartsough: Yes, and then when I was 18, I went on the walk from Philadelphia to the United Nations in 1958 when we asked all nations to stop nuclear weapons testing. That was the year when four Quakers risked their lives trying to sail the Golden Rule into the nuclear weapons testing area of the Pacific Ocean.

That motivated many of us to walk from Philadelphia to the United Nations — about 100 miles — calling for an end to nuclear weapons testing. When we got to New York, we had about 500 people marching down the streets to the United Nations. At the time, it was the largest peace protest I’d ever seen in my life [laughing]. It was very inspiring.

Spirit: The anti-nuclear movement may have started small but it would ultimately lead to far larger demonstrations at Livermore Lab and all over the nation.

Hartsough: Livermore was the place that had developed the hydrogen bomb, the MX warhead and the neutron bomb, which could kill all the people and leave the buildings intact. So I was absolutely delighted when people in the Bay Area decided to begin a campaign to convert the Livermore Laboratory from building the next generation of nuclear weapons to doing positive peacetime research.

Spirit: Thousands of people were arrested for blockading that holocaust laboratory. The Livermore actions were a very dramatic confrontation with the federal government.

Hartsough: That’s right. And when more than a thousand of us were in jail in 1982, and again in 1983, the authorities used fear as a means of trying to control us. But I think most of us had overcome that fear and we were willing to spend two weeks in jail or whatever it took to try to help turn the arms race around.

Instead of being afraid while in jail, we used that time to organize workshops and trainings. People shared their life stories and Dan Ellsberg taught us everything he knew about nuclear weapons development. It was a massive teach-in! I organized a strategy game using civilian-based defense as a nonviolent means of defending a country. So we became much stronger through that time in jail.

The authorities finally realized that their system of intimidation and fear through holding us in jail was not working. They decided it was a poor use of their money to give us free room and board to do workshops to strengthen our movement [laughing].

Spirit: We found out later that we were nearly bankrupting the city of Livermore because of the massive costs of imprisoning thousands of people, and the huge court costs.

Hartsough: That’s why in subsequent years, after they arrested us they would never even bring charges because they realized it’s not going to stop us.

Spirit: The nuclear arms race was so massive, and the military-industrial complex so powerful, that many thought resistance was futile. Yet those who actually stepped forward and resisted the arms race found great new levels of hope.

Hartsough: What our government wants us to do is to just sit back and either support or silently condone all of the horrendous things they do, including developing nuclear weapons which could put an end to life on earth.

Having people who are willing to speak out and get in the way of the arms race through blocking the entrances at Livermore Lab is the kind of thing we had hoped the German people would do during the Third Reich in Nazi Germany. They could have said, “Enough is enough! Stop this madness!”

And here at Livermore, we had thousands of people who were willing to do that. And this resistance was also happening at Los Alamos Laboratory and the Nevada Test Site, and all over Europe. A massive movement arose in Europe and at Greenham Common in resistance to Cruise and Pershing missiles. It was and is an example of nonviolent people’s power saying no to the madness that our government was trying to inflict upon us. And that gives me hope.

The Pledge of Resistance

Spirit: Many anti-nuclear activists soon began working with the Pledge of Resistance to oppose U.S. military intervention in Central America. What role did you play in forming the Pledge?

Hartsough: After many of us had experienced the horrors of the wars in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala, we felt that we had to do something even deeper to try to stop the killing. Under Reagan’s presidency, his number-one foreign policy objective was to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua by supporting the Contras’ attacks.

So we formed the Pledge of Resistance, which organized thousands of people all over the country who signed a pledge saying if the United States escalated the wars in Central America, we would do nonviolent direct action to protest the atrocities the U.S. government was inflicting.

For several years, we were carrying out actions every time Congress voted more money for these wars, and when the United States blockaded the ports of Nicaragua, and when the Jesuit priests were murdered and the nuns were killed in El Salvador. We would have actions where hundreds and hundreds of us would be arrested.

Here in San Francisco, we shut down the Federal Building a number of times during those years, and there were protests at federal buildings and military bases all over the country.

Spirit: Your Nonviolent Movement Building Program played a key role in supporting the Pledge in the Bay Area.

Hartsough: Our program supported Ken Butigan to work on helping develop the Pledge of Resistance. You and I organized nonviolence trainings for the Pledge, and trained nonviolent trainers. That played a very key role in helping influence the nonviolent spirit and tone of the actions.

We funded the Pledge of Resistance nonviolent training handbook and it became a manual for people all around the country. [Editor’s note: Ken Butigan and Terry Messman were members of AFSC’s Nonviolent Movement Building committee and co-authored Basta: No Mandate for War. A Pledge of Resistance Handbook.]

Spirit: How would you analyze the effectiveness of the Pledge of Resistance?

Hartsough: A lot of people that were involved in the Pledge around the country came out of the religious community. Somebody in the White House said at one point, “We could go ahead and overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua if it weren’t for these Christians.” Meaning the Pledge of Resistance!

We were a formidable force. Every time our government did anything to escalate these wars, they would have people doing sit-ins in Congressional offices, shutting down federal buildings, and marching in the streets, and they’d have to put hundreds of people in jail. That was a real problem for them.

I think the Pledge was an example of American people who were in touch with their consciences, and were willing to put their freedom on the line, and spend time in jail if necessary, to speak out against the horrors that our government was involved in. We desperately need that spirit again as we resist wars in the future.

Nuremberg Action Group

Spirit: How did you become involved with Nuremberg Action Group in blocking shipments of weapons to Central America from Concord Naval Weapons Station?

Hartsough: Brian Willson, Charlie Liteky and members of Veterans for Peace had fasted on the steps of the U.S. Capitol for 40 days to try to stop Congressional support for the wars in Central America. Brian Willson then went on one of the veterans’ peace action teams to Nicaragua.

When he came back, he was in tears at what he had seen in Nicaragua. The Contras had come across the border to attack communities in Nicaragua, including children’s nurseries, cooperative farms and medical clinics. He said, “We’ve got to do much more to stop this.”

Spirit: It’s interesting that military veterans led some of the first protests. The Nuremberg principles were established during the trial of Nazi military officials and leaders accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes against peace.

Hartsough: Yes. We called these actions Nuremberg Actions because we felt we were upholding not only God’s law, but international law: the Nuremberg principles. So indiscriminately killing innocent men, women and children in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala are crimes against humanity. And to do nothing in the face of those war crimes is to be complicit in those war crimes. So we were upholding international law by trying to stop these arms shipments.

Spirit: Why did the veterans for peace choose the Concord military base to begin upholding the Nuremberg principles?

Hartsough: Concord Naval Weapons Station was a major shipping point for munitions to Central America, so in 1987, we decided Concord was the place where we needed to hold a blockade. On June 10, 1987, Russ Jorgenson, Dorothy Granada, Wendy Kaufmann and I were arrested for sitting on Port Chicago highway and blocking the first munitions truck at Concord. We spent the weekend in jail.

Then people held a vigil at the Concord base every single day of the entire summer. Brian Willson decided that starting on September 1, 1987, he would begin a fast and block trains carrying munitions. He had written to the Navy and to the press that the government had a choice to either stop the arms shipments to arrest them and take them to jail, or run over them.

Spirit: So Navy officials had advance notice that Brian and others would be sitting on the train tracks.

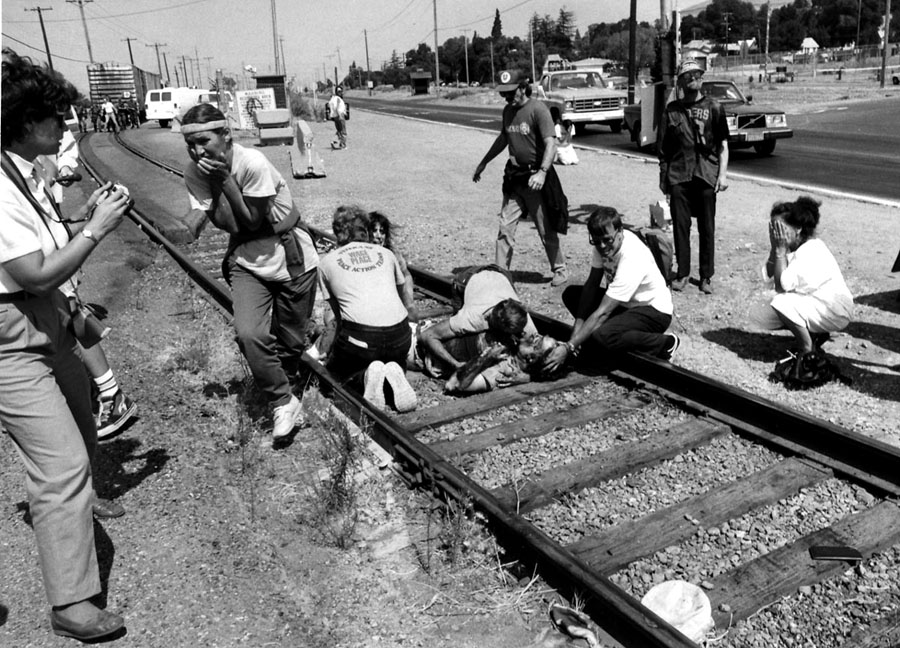

Hartsough: There were three veterans that decided to block the trains on September 1. We had an interfaith worship service and a press conference and then sent a delegation to tell the Navy again that we were going to be blocking the trains. About 11:30 in the morning, after the worship service, the train started moving towards us.

We had a big banner across the tracks saying, “Stopping the War Starts Here: Nuremberg Actions.” I was in front of the group looking at the two guys on the train and I was yelling at the top of my voice: “There’s people on the tracks. Stop the train!” The train actually hit my arm and knocked me down, just outside the tracks.

Instead of slowing down, the train was picking up speed as it approached Brian Willson and Duncan Murphy and David Duncombe sitting on the tracks. Duncan and David jumped off the tracks. Brian was sitting on the tracks with his legs crossed and the train ran over him. I could see Brian being smashed from one side to another and the train was grinding up his body, with blood spurting everywhere.

As the train passed by, I found one of Brian’s severed legs with a shoe and went running toward him. There was a big hole in his head, so I put my hand over the hole to try to hold the blood from gushing out. His wife of 10 days, Holly Rauen, was a midwife and had medical training and she was able to put a tourniquet around his leg to stop the blood flow.

The Navy ambulance came and I said to them, “Take this man to the hospital. He’s dying.” And they said, “We’re not allowed to.”

Spirit: That is so heartless. It makes you sick. They were just following orders, like the original Nuremberg defendants.

Hartsough: So somebody had to run to a pay phone, and it was another 23 minutes before another ambulance came. None of us thought we’d ever see Brian alive again. He went through many hours of surgery. Bones throughout his body were broken, his skull had been fractured, and there was a big hole in his head. One leg was gone and the other had to be amputated.

Luckily after that surgery, he was still alive. When I went to see him in the hospital, he had bandages all over his whole body, and bandages around his face so I could only see his eyes. He was not only alive, but his commitment to nonviolence and his commitment to continuing the struggle at Concord had intensified, if anything.

We had decided to have a rally that Saturday to recommit ourselves to stopping the trains and stopping the arms shipments. I asked him if there was anything he’d like to say to the rally, and I recorded his statement.

Brian said, “We have to continue this struggle because these bombs are killing people in Central America, and as soon as I can get out of the hospital, I’ll be back there with you.”

We had 9,000 people out there at Concord the next Saturday, including Jesse Jackson and Joan Baez and Rosario Ortega, the wife of Daniel Ortega.

We now know it was a decision in Washington, D.C., not to stop the trains, but to essentially scare us into stopping our actions against the war.

Spirit: Instead of stopping Nuremberg Actions, the Navy’s assault on Brian Willson outraged people, and inspired them to come out in more massive numbers than ever before.

Hartsough: Exactly. For close to three years, the Nuremberg Action Group had people blocking the trains and the trucks every day. Sometimes they would have to arrest two busloads of us to get us off the tracks so they could run their trains and have their war and keep killing people in Central America.

Spirit: Brian Willson beat all the odds and not only survived, but dedicated his life to working for peace and justice.

Hartsough: He has spent the rest of his life acting on that belief that we’re really all brothers and sisters. And he was a very inspiring example to people all over the world that there are Americans that care enough about the death and destruction that our government is causing that they’re willing to put their lives on the line to try to stop it.

Spirit: Hasn’t he become a hero to people in Nicaragua and Central America?

Hartsough: Yes, to people in Nicaragua and throughout Latin America, and people in Israel and Palestine, and many other countries. He was invited to come everywhere.

They wanted to meet this person who really acted on his belief that American lives aren’t more important than everybody else’s lives, and we have to speak out to stop this madness — not just with words, but with our bodies.

Brian Willson’s Dance of Defiance

Spirit: One of the most inspiring things I ever saw was on the 25th anniversary of Nuremberg Actions. Brian returned to the Concord base to speak out for peace, then he danced on his prosthetic legs on the same railroad tracks where he had lost his legs.

Hartsough: Governments have the power to throw us in jail and shoot at us and intimidate us, but they don’t have the power to kill our spirits, and they certainly didn’t kill Brian’s spirit. Our actions at Nuremberg were an example of what people all over this country can do, and have a responsibility to do, if we’re to stop our government from fighting one war after another, and causing misery around the world.

Spirit: Can you remember back to what you felt the very first time you visited Brian in the hospital right after he was run over by the train — but before all that inspiring stuff happened with 9,000 people gathering in solidarity at Concord?

Hartsough: It was horror, especially that first day when this had just happened. Here we were still at the tracks, and our dear friend had been taken off to the hospital and was presumably going to be dying. Brian and I had talked about doing that first action together, and up until that morning, I was planning to be on the tracks.

But we had an agreement that anyone who would block a train or truck had to go through a nonviolence training first. There were a bunch of people out at the tracks who wanted to block a train, and I was the only person there who could do a training. So I agreed not to block that first train, but to do a nonviolence training and then we would block the next train.

Brian and I had been two of the people that had envisioned and planned and organized this. So I felt tremendous responsibility that I had caused this guy’s death. Then, when I found him alive — and his spirits were very much alive even though he was all in bandages and without his legs — there was tremendous joy in my heart that he had survived this.

This developed a very close kinship between the two of us. I realize how, every day since then, Brian has had to suffer. He has suffered from not having his legs, and he had to suffer the physical and psychic pain from that train hitting him. So I’ve wanted to be supportive of him in every way I can. And we’re obviously very, very dear friends. It’s inspiring to me to know somebody with as much love in his heart as Brian has for all the people in the world.

Arms Broken by Police at Concord

Spirit: It can be costly to resist war crimes. The Concord police also began using torturous pain holds to remove nonviolent demonstrators from the tracks.

Hartsough: Yes. Three of us had our arms broken by police using pain holds in November of 1987 — Rev. David Wylie, Jean Bakewell and I. I was kneeling on the tracks when the weapons train was approaching, and the sheriff’s deputy told me I had to get off the tracks because the train was coming. I said, “I’ll be happy to get off the tracks when you stop shipping arms to kill people.”

So he grabbed my arm and began twisting it, and when it got so painful I had to get up and start walking with him. I walked about 20 feet, and he said, “This is to make sure you get off the tracks next time.” Then he gave my arm another twist and broke it. I went unconscious.

Spirit: Didn’t the three of you win a lawsuit that barred the police from using these pain holds?

Hartsough: It was not just pain holds, but they were breaking bones. The ACLU decided to sue them and it was finally settled out of court because the government didn’t want to go to trial. But they agreed to give $50,000 to cover our medical expenses. I gave my part of it to Witness for Peace and Peace Brigades International. The most important part of the settlement was an agreement on the part of the Sheriff’s Department in Contra Costa County not to use violence against nonviolent demonstrators.

The Occupy Movement

Spirit: You went on several marches with the Occupy movement in Oakland and San Francisco, and you also helped organize forums where the issue of nonviolence in Occupy was debated. On a march to the Port of Oakland, you said that Occupy was the most remarkable movement you had been involved in. Why did you think that then, and what do you think of its significance in retrospect?

Hartsough: I think the Occupy movement was a tremendous outpouring of people throughout this country in resistance to the terrible inequality of this nation. Instead of a democracy of, by and for the people, we have a plutocracy — a government of, by and for the rich and the corporations. In hundreds of cities across the United States, people tried to stop business as usual, and demanded that our country get back to its basic values and principles.

I think like all other social movements, in order to have a chance, you have to build a mass movement, and you have to be willing to put your lives on the line, blocking the banks and challenging the corporations that are stealing our democracy. And you have to keep marching even if the police say it’s illegal. And all that was happening. And the spirit among the people that were part of that movement was absolutely overwhelming. It did bring together homeless people and students and old people and labor unions and religious communities. I think we had tremendous potential and I hope we still do.

Spirit: How do you understand the swift rise and sudden fall of Occupy?

Hartsough: I think the federal government decided it was a threat to have tens of thousands of people marching and camping out in the parks and challenging the unjust institutions so dramatically. So they decided to come down very, very heavy on the Occupy movement. Partly, it had gotten to be winter and people were cold and wet and tired. I think it was a weakness, if you will, that we allowed ourselves to be intimidated by the government repression and the violent tactics by the police when they cleared the encampments and arrested people.

Fear and repression is the Achilles’ heel of any movement, and almost all governments will use fear as a way of controlling people. Unfortunately, we didn’t have the understanding and commitment to realize that was what the government was doing, and not let them get the upper hand.

But I think the Occupy movement does continue to live and those people have not just disappeared. Occupy people are challenging foreclosures around the country. They’re still there and working in many smaller, less visible ways. I still think a powerful nonviolent movement can be resurrected and turn this country around.

Arrested in Kosovo

Spirit: Tell me about the events that led to your working with activists in Bosnia and then your arrest in Kosovo.

Hartsough: In 1996, I went to Bosnia with the Fellowship of Reconciliation and that was right after the shelling of Sarajevo had ended. We saw literally hundreds of cemeteries all over Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, all with fresh graves from that war.

In Kosovo, more than 90 percent of the people were Albanians, and they were being ruled by less than 10 percent of the people who were Serbs. It was an apartheid country. Many Albanians had lost their jobs, and could not study in the university. Instead of getting guns and turning to armed struggle, they were choosing nonviolent means to challenge that oppression and that apartheid regime.

So I decided to go there and I met Adem Demaci, who had spent 29 years in prison, very much like Nelson Mandela. He was the head of the human rights commission there. I met students that were challenging their exclusion from the university. I met political prisoners, women’s organizations and teachers. I spent a couple months with them and they were all saying they were facing an apartheid regime.

They told me that Kosovo was an explosion waiting to happen, and they wanted to form a more active and assertive nonviolent struggle. To do that, they needed international people to come to Kosovo and be present with them to make it safer. They asked me to find international people to come and help them engage in nonviolent struggle. When I went back to Kosovo with a small group of American students in the spring of 1998, hundreds of thousands of people were marching in the streets — everything from young families with their babies in strollers, to old people with their canes. Yet, the massive protests barely got any publicity in the rest of the world.

I began doing nonviolence trainings of the students, which they had asked for, and the next day, all five of us Americans were put in prison, and we got major publicity for our arrests around the world. It was kind of ridiculous because hundreds of thousands of people marching nonviolently were ignored, while five internationals who got arrested for trying to support these folks got all this publicity.

Spirit: How long were you held and what were conditions like in the jail?

Hartsough: We were sentenced to 10 days in jail, but after the third day, there had been so much publicity around the world that they came to the jail and took us to the Macedonian border and stamped in our passports that we couldn’t come back for ten years. We used the publicity to try to bring attention to the nonviolent struggle in Kosovo and the need to support it.

The conditions in jail were terrible. It was very cold, and there was no heat. They had shaved our heads. There were a hundred rules posted on the wall and the first rule said: “Obey all the rules.” It was pretty harsh and inhumane.

Then, in 1999, when some more ethnic cleansing had started, President Clinton went on international television and said we have two choices: We can look the other way and do nothing, or we can go in and start bombing. From my perspective, neither of those alternatives are acceptable. We had a third alternative, which our country and the world had refused to take, and that was to support the nonviolent struggle. That was a terrible lost opportunity. If we had done that, I think we had a good chance to help make that transition to a more democratic society happen peacefully, rather than through a horrendous war. The hatred that exists now between people in Kosovo and the Serbs will last for generations. And that’s what happens in every war.

The Nonviolent Peaceforce

Spirit: Is that what led to your work with the Nonviolent Peaceforce?

Hartsough: That experience was the impetus to start the Nonviolent Peaceforce. I realized we needed hundreds of trained, nonviolent peacekeepers — courageous people that could go to Kosovo or anywhere there was a nonviolent struggle to help support those folks to successfully challenge oppression.

In the spring of 1999, the Hague Appeal for Peace was happening in the Netherlands where 9,000 peace activists from all over the world came together to look at how we could end war. So a number of us who were at the Hague Appeal committed ourselves to building a global nonviolent peace force. We started a two-year process of sharing this vision with people from other parts of the world. Then, in 2002, we held our founding conference in Surajkund, India, outside of Delhi, and started the Nonviolent Peaceforce, with peace activists from 49 countries present.

We now have a couple hundred trained international peacekeepers that can go into conflict areas at the invitation of local peacemakers, and help protect civilians that are being killed or injured in conflicts. About 80 percent of the people that die in wars and armed conflicts are civilians, many of them children. We’re also there to protect human rights workers and local peacemakers whose lives are endangered.

We have been in Sri Lanka. We’re presently in Mindanao in the Philippines where there has been a decades-long struggle between the government military and the Muslim community. We’re also in South Sudan which is in tremendous upheaval right now, and we’re starting a project in Burma where there are still some major conflicts.

Spirit: What was your role in developing the Nonviolent Peaceforce?

Hartsough: Mel Duncan and I were seen as the cofounders of the Nonviolent Peaceforce. We were seen as the people who really took this vision and continued to reach out to people all around the world to help bring this vision into being. I was the strategic relations director and was responsible for reaching out to organizations and groups all around the world.

We wanted the Nonviolent Peaceforce to not just be a group of North Americans. We wanted this to be truly a global force of people from all over the world. Both our decision-making body and our volunteers on the ground are really a mixture of people and races and nationalities from the whole world.

Spirit: This idea seems to build on the work of groups like Witness for Peace and Peace Brigades International.

Hartsough: Yes, I had worked with Peace Brigades International and Witness for Peace, and saw that nonviolent peace teams can have a very important impact, and we wanted to expand this. Gandhi first envisioned a Shanti Sena, or nonviolent army, so this idea has been kicking around for a long time. And it was very exciting to actually find the people in different parts of the world who wanted to realize this vision of Mahatma Gandhi.

Today, the United Nations and many friendly governments are beginning to understand the power of nonviolent peacekeeping as an alternative to armed peacekeeping. Our hope eventually is to have this seen as an alternative to war and violent intervention.

Peace delegations in the Middle East

Spirit: Have you led peacemaking delegations to countries in the Middle East?

Hartsough: I have led two peace delegations to Iran, and one to Israel and Palestine in the last four or five years. Bush called Iran part of the Axis of Evil, and these countries were seen as the ultimate enemies. So what we were really doing was just getting to know the Iranian people as people. When you know people, it’s very hard to think about killing them or blowing up their society.

We met with members of Parliament and religious leaders and all kinds of people in the country, and then came back to share their stories. Iran has not started a war with another country in 200 years. The United States overthrew their democratically elected government in 1953. [Editor: Iranian Prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh was overthrown in 1953 by the United States in a coup after he nationalized Iran’s oil industry.]

The U.S. also shot down a civilian airliner and never apologized for that. We have troops and bombers surrounding their country, and yet we see them as a threat to us. That reality motivated us to try to stop a war with Iran, and to get our nation to resolve its conflicts at the negotiation table, not on the battlefield.

Spirit: What happened on your peace delegation to Israel and Palestine?

Hartsough: Scott Kennedy and I led a delegation to Israel and Palestine in 2009-2010. What most influenced me is that, similar to Kosovo, there is a very broad-based movement, especially in the West Bank, where Palestinians have been challenging the wall, and challenging their apartheid system where they are treated as second-class citizens.

They have been resorting to nonviolent struggle, but unfortunately, Israel has not responded very positively to that nonviolent struggle. And there are also many Israelis that are very committed to justice for Palestinians, and are actually joining in weekly nonviolent demonstrations across the West Bank. It is important to try to bring this to light for the rest of the world.

This is a nonviolent movement where, week after week, people are marching to the walls that are separating their communities from their fields, and they are being tear-gassed and shot with rubber bullets. And there are Israelis from the religious community called Rabbis for Human Rights that are supporting them and acting in solidarity with them.

Israel is using massive bombing and a total blockade and locking the borders so people can’t get in or out — all in an effort to try to find security. It is exactly the opposite of what is needed. The only real peace that can be created there is a peace where there is a sense of justice, and where every person is respected for their religious beliefs and nationality.

Seeking A World Beyond War

Spirit: It is fascinating to me that, after a lifetime of being involved in many idealistic campaigns for peace, instead of becoming more “practical” or “realistic,” you are now involved in perhaps your most utopian campaign of all — a World Beyond War. Is there any real hope of abolishing warfare?

Hartsough: It’s called World Beyond War: A Global Movement to End All Wars. The overwhelming numbers of people in the world do not benefit because of war, and are suffering because of war. Our governments continue this anachronistic practice of fighting wars because that’s how they think they’ll get security.

We know that wars are not working. Wars are bankrupting us. Trillions of dollars are being wasted on wars and preparation for wars. And that forces the governments to cut funds for every social program and from schools and environmental programs and parks and homeless programs and low-income housing and programs for the elderly and children.

Spirit: How are peace activists building this movement to abolish war?

Hartsough: We have over 4,000 people who have signed a Declaration of Peace. [This is available at www.worldbeyondwar.org.] We have 68 countries where people have signed the Declaration of Peace. People who have signed this declaration are committed to not engage in or support wars of any kind and to work nonviolently to end all wars.

We have committees that are working on strategy, fundraising, outreach, nonviolent training, and the use of social media. We have people doing the research to document that wars are not working and that there are viable alternatives to war right now. The campaign is still in its initial stages. We have to do a tremendous amount of education not only among peace people, but all the groups that could benefit by ending war.

Ending war is possible if the people of the world realize that those of us who want peace are the massive majority, and we have to force our governments to listen to us. We need to challenge our governments to stop this nonsense, and if they don’t listen to us, we will engage in massive nonviolent resistance.

Spirit: You have recently written a book about your lifetime work for peace and justice. What can you tell us about it?

Hartsough: My book is Waging Peace: Global Adventures of a Lifelong Activist. It shares my experiences with nonviolent movements over the last 60 years. I think that we all need to be inspired by the stories of people that have been engaging in nonviolent resistance around the world.

Hopelessness is maybe our greatest enemy. So people end up feeling disempowered, and that there’s nothing we can do to change things. In this book, I’m trying to challenge that sense of hopelessness and powerlessness. The status quo wants us to believe that we’re powerless and that we’re nobodies.

But people in the Philippines, in Liberia, in Eastern Europe, in Tunisia, in Egypt, and in many other parts of the world understand that they’re not powerless, and that nonviolent struggle is the most effective means to challenge oppressive governments. This book shares my own experiences with nonviolent movements that have made an enormous difference in changing the world.

The Three Most Inspiring Movements

Spirit: In light of your involvement in countless social-change movements, what are the three movements that you found to be the most inspiring?

Hartsough: I would say the Civil Rights movement in this country, the Occupy movement, and the movement against the Vietnam War.

Spirit: Why do these three movements stand out as the most extraordinary?

Hartsough: During the movement to end the Vietnam war, communities all across this country — churches and labor unions, university and high school students, women’s groups — decided that the war in Vietnam was a lie and was killing millions of people in our name and with our tax dollars, and they were going to have to stop it. That same commitment is what we have to create again in the World Beyond War movement today.

The Civil Rights movement started with one woman, Rosa Parks, in Montgomery, Alabama. It started with four students in Greensboro, North Carolina. Both of those actions were sparks that ignited people all over the South, and then eventually people all over the country, to stop the insanity of segregation and second-class citizenship. People put their own lives on the line to create a society that could truly be called a just and democratic society. Those sparks ignited a whole movement of thousands of people willing to risk arrest and violence.

The Occupy movement was a real sign of hope. Occupy was the most recent of these movements and, again, it was sparked by people at the grass roots of our society. People saw a totally serious flaw in our society. They saw that the government is really being controlled by the rich and the corporations while ignoring the well-being of the people. We’ve got to take back our government for the people and the Occupy movement was trying to do that. It was inspiring that so many people left their comfortable homes and went out on the streets and acted to get this country back on track.