by Terry Messman

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]uring their hard-fought struggle to overcome nearly impossible odds and win voting rights for African American citizens who had been disenfranchised for 100 years, civil rights activists marched down the long and treacherous road that led from the brutal battlefield of Selma, Alabama, and through a seemingly endless gauntlet of beatings, bombings, bloodshed, gunshots, martyrdom and a tri-state assassination conspiracy.

Even though their nonviolent efforts to win the right to vote were met with some of the most shocking violence of the entire civil rights era, the Freedom Movement stood its ground and claimed perhaps its most significant and far-reaching victory for human rights — the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

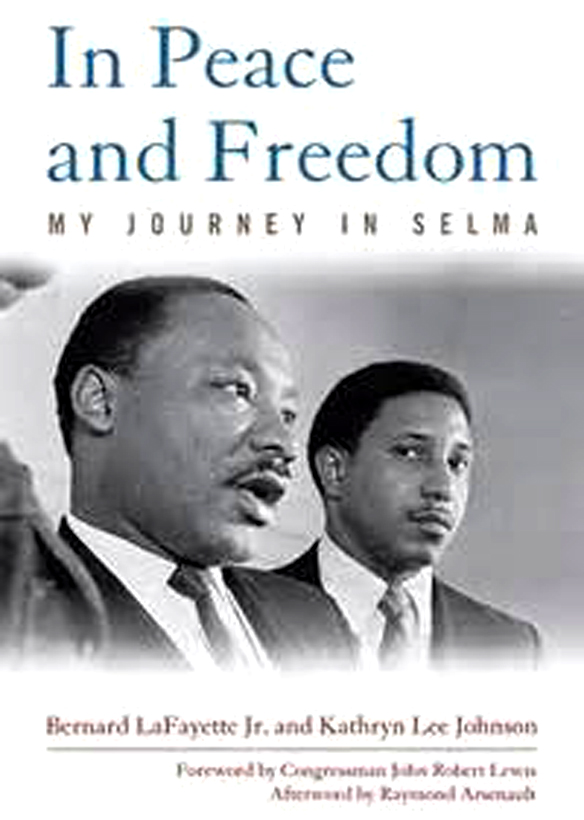

As a very young man, Bernard LaFayette was chosen to become the key organizer of this dangerous and bloody struggle, and he offers a fascinating insider’s look into the Selma campaign in interviews and in his recent book, In Peace and Freedom, My Journey in Selma. The lessons in this highly insightful case study in community organizing are deeply valuable and relevant to today’s human rights activists.

Find The Cost Of Freedom

In opening up this chapter of the Freedom Movement to unearth its lessons, it is important to approach it, not as some academic case study in nonviolence, but with the clear-eyed realization of the terrible price that was paid in bloodshed and the loss of life.

For LaFayette has given us something far more profound than just another case study of nonviolence. He has also opened our eyes to the heartbreaking sacrifices made by decent and compassionate people such as Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo and Rev. James Reeb, who selflessly gave their very lives in their commitment to fighting for the most basic of human rights.

This, then, is history as written in the flesh and blood of thousands of people who found the courage to march for justice. It is a story of dreams deferred and justice long denied, a family saga of grandfathers marching alongside their grandchildren, a struggle for freedom consecrated by the blood of martyrs.

Sit-Ins and Freedom Rides

Bernard LaFayette was only 22 years old when he was chosen by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to be the director of its Alabama Voter Registration Campaign in January 1963. Yet, even at this young age, LaFayette already had become a seasoned activist after being arrested two years earlier in 1960 during the restaurant sit-ins organized by the Nashville Student Movement, a nonviolent campaign to integrate public facilities that ignited the idealism of a new generation and spread like wildfire through the Deep South.

Then, one year after the Nashville sit-ins, came the next milestone on his road to Selma. In 1961, LaFayette decided to become a Freedom Rider, perhaps the single most dangerous calling a young activist could answer. He provides a harrowing account of being brutally beaten by a mob of white racists who attacked a busload of Freedom Riders at the Montgomery bus station in May 1961.

Yet, LaFayette is always the indefatigable teacher of nonviolence, selflessly teaching its lessons to a new generation, instead of drawing attention to his own accomplishments. So, instead of focusing on his own dedication in facing the horrific assaults on the Freedom Riders, his real message is to teach us how nonviolent activists can face overwhelming levels of physical violence and still keep their spirits intact and their movement alive.

“In the Montgomery bus station a ranting mob viciously attacked us. Several of us were severely beaten. However, we defied all expectations. We didn’t run, we didn’t fight back. We got back up when slammed to the ground, and looked our attackers directly in the eyes, fighting violence with nonviolence. In spite of our injuries, with many of us bleeding and battered, we got back on the bus and continued our ride toward Jackson.” [In Peace and Freedom, p. 11.]

Selma: The Most Hostile City

Far from being deterred by the violent attacks that battered the Freedom Riders, the young activist was more determined than ever to put the nonviolent teachings of Martin Luther King and James Lawson into practice in one of the most hostile and intolerant of southern cities — Selma, Alabama.

Selma was considered so dangerous and implacably racist that the SNCC leadership had totally written it off as an impossible area to organize. When LaFayette asked James Forman, the executive secretary of SNCC, to appoint him as director of the Voter Registration Campaign in Selma, he was told that SNCC had just removed Selma from the list of possible organizing sites after two groups of SNCC workers had returned from scouting the city and reported, “The white folks are too mean and the black folks are too afraid.”

Yet LaFayette remained dedicated to putting the teachings of nonviolence to work in a city where they would meet the toughest test imaginable. Forman finally relented and appointed him director of the voter registration campaign in Selma.

As soon as he arrived in Selma in January 1963, LaFayette began bringing together an embryonic organization of Selma residents to carry out a systematic voter registration campaign that, only two years later, would literally transform the face of a nation, when it catalyzed the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Tri-State Assassination Conspiracy

Yet LaFayette’s central role in this momentous struggle was almost erased at the beginning of his Selma sojourn. On June 12, 1963 — the same day that legendary civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi — Dr. LaFayette and Rev. Benjamin Cox, a leading organizer for CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) in New Orleans, were also targeted in coordinated assassination plots.

Even though the murder of Medgar Evers is now enshrined in the nation’s memory as a courageous sacrifice for the Freedom Movement, the story of the two other intended victims who were targeted by murder plots is almost unknown. LaFayette’s book offers a gripping, first-person account of the coordinated, same-day murder plots that the FBI called the “Tri-State Conspiracy” to assassinate three key civil rights leaders in Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana.

This assassination conspiracy was carried out just hours after President John Kennedy had given a major speech on national television in support of civil rights on June 12.

On the same evening that Evers was murdered by an assassin when he pulled into his carport at his home in Jackson, Mississippi, LaFayette was attacked and nearly beaten to death when he returned home in his car after a voter-registration meeting in Selma.

As he arrived home, two white men in a nearby parked car asked him to give their stalled vehicle a push. When the unsuspecting LaFayette got out of his car to help the men, they savagely attacked him without warning, smashing his head with a crushing blow from a pistol butt that knocked him to the ground. When he rose up and stood his ground, refusing to run, the attackers pounded his head with crushing blows, again knocking him to the ground. Each time the men struck him, LaFayette stood up again, refused to run or defend himself, and looked his assailant in the eye.

But then, the would-be assassins aimed a gun point blank at his face, preparing to shoot the defenseless activist. At that moment, his neighbor Red ran out, and pointed a rifle at them. LaFayette hollered, “Don’t shoot him, Red!” Adhering to nonviolence even at great risk to his own life, LaFayette stood between the two armed men with his arms outstretched. The attackers jumped into their car and sped off, and LaFayette was taken to the hospital.

During the brutal assault, LaFayette said that he felt a sense of “spiritual empowerment that allowed me to feel an extraordinary sense of internal strength instead of fear.” Even though he was face to face with death, he wrote, “I felt an intense force that seemed to lift me up emotionally, even though I didn’t know what would happen next. It was a surrendering of life, in a sense, and I was prepared.”

He realized that this “surreal feeling” had happened only twice in his life, both times when he was under physical attack. “I view it as a form of resistance, with support from a power beyond myself,” he wrote. [In Peace and Freedom, p. 75.]

A Turning Point in the Selma Campaign

The nearly lethal violence directed against LaFayette after he had only worked for a few months in Selma seemed to confirm the initial decision by the SNCC leadership to entirely avoid any campaign for civil rights in Selma. A lesser man — and a lesser movement — would have abandoned the entire organizing effort in Selma right then and there.

Instead, the assassination attempt boomeranged on the assailants. The black community had been oppressed for so long by threats of terrible reprisals — fearing everything from the loss of jobs to the loss of their lives — that they were intimidated into being silent, afraid to speak out publicly even for their right to vote.

The assassination plot seemingly confirmed all their worst fears, yet it became a turning point in the struggle toward freedom. LaFayette explained: “The feelings of blacks in Selma toward me changed after that night because they realized I was prepared to give my life for a cause that would serve them. There was a different climate, a new attitude. People not only sympathized; they offered genuine support.”

He now found that many more people were committed to attending the mass meetings and voter registration classes, and long lines of people began bravely standing up for their rights at the voter registration office, where they willingly risked arrests and beatings by the notoriously brutal Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies.

Sheriff Clark and other Selma officials wore buttons proclaiming “NEVER!” to show that they would never tolerate any attempts at integration and voter registration. They drove their segregationist message home by violently attacking and arresting Selma citizens as they peacefully attempted to register to vote. Yet hundreds of people from all walks of life found the courage to challenge Sheriff Clark and the brutal apparatus of segregation.

This is the “boomerang effect” of nonviolence that Gus Newport of the National Council of Elders has described. This boomerang effect has made an unexpected appearance in many seemingly hopeless nonviolent campaigns when an oppressed people suddenly discover the spirit of resistance rising from within at the very moment when the authorities have attempted to destroy a movement with violent repression.

Too Many Martyrs

Medgar Evers is now revered as a legendary hero of the Freedom Movement. As the Mississippi field secretary for the NAACP, Evers had defied several assassination threats and kept working fearlessly for civil rights, until he was shot in the back at his home in Jackson by a rifle-bearing member of the White Citizens’ Council and the Ku Klux Klan, Byron De La Beckwith.

In the years since his death, Medgar Evers has been honored in movies and books and songs; his memory and legacy have been celebrated at Arlington National Cemetery; and a memorial statue of the slain civil rights icon was erected in Jackson, Mississippi, in June 2013.

Bob Dylan honored Evers in the song, “Only a Pawn in their Game.” Dylan sang, “Today, Medgar Evers was buried from the bullet he caught. They lowered him down as a king.”

The folksinger Phil Ochs, deeply committed to the cause of civil rights as a musician and an activist, wrote an anthem, “Too Many Martyrs,” with an unforgettable description of Evers’ murder.

“He slowly squeezed the trigger, the bullet left his side,

It struck the heart of every man when Evers fell and died.”

The “Death-Day” Card

CORE activist Rev. Benjamin Cox avoided assassination because he just happened to have traveled out of New Orleans that fateful night. “That chance trip saved his life,” LaFayette writes.

Rev. Cox had been arrested many times for organizing sit-ins that succeeded in integrating several restaurants, including McDonald’s. In May 1961, Cox and 12 other activists became the original Freedom Riders, riding the bus from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans.

After the FBI told Cox and LaFayette that they had been targeted in the tri-state conspiracy that claimed Evers’ life, the two men realized they had escaped death by the narrowest of margins.

With a grim sense of gallows humor, LaFayette wrote: “We’ve been friends for many years and sometimes Cox sends me a ‘death-day’ card instead of a birthday card!”

Yet even as the Black community in Selma found new reservoirs of courage and commitment in the wake of the assassination attempt on LaFayette, the 16th Street Baptist Church in nearby Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed on September 15, 1963, by the Ku Klux Klan, killing four young girls attending Sunday School and injuring hundreds more.

Only two months later, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. The twin tragedies threatened to tear the heart out of the movement.

LaFayette wrote, “The people in Selma had been hopeful with Kennedy, and they were now filled with a profound sorrow and grief, having lost an influential supporter of the civil rights movement.”

Beyond the overwhelming grief came the unsettling realization that violence could strike down anyone at any moment in the struggle for freedom.

“Many of us felt that if the most powerful leaders in the world could not be protected, then the common person, particularly black persons, certainly had no protection at all,” [In Peace and Freedom, p. 104.]

The Magnificent Movement

And that is when the movement rose up and magnificently met the challenge. People persevered in spite of the deaths of innocent young girls in church. They persevered in the face of the assassinations of Medgar Evers and President Kennedy. In the face of death threats and bombings and the savage brutality of Selma Sheriff Jim Clark, the movement defied all expectations and grew stronger in commitment.

Nonviolent resistance has been defined as a spirit of “relentless perseverance.” LaFayette watched as that spirit of perseverance emerged in Selma.

“We considered ourselves soldiers in a nonviolent army and would continue to fight against violent acts with nonviolence. Violence was never a deterrent for us. We believed that if we sustained the movement in spite of the violence, we would succeed and bring about the changes we sought.”

Due to the never-say-die courage displayed by thousands of people from all walks of life, Selma became one of the most significant battlegrounds in the struggle to win civil rights and voting rights for an entire nation.

It is customary in our culture to believe that history is made by generals, presidents, and powerful corporate leaders. In Selma, Alabama, and throughout the Deep South, the common people rewrote the history books. The courage of ordinary people turned out to be the most essential ingredient in overcoming a systematic form of racist discrimination that had for decades prevented nearly all black citizens from being allowed to vote.

Bloody Sunday in Selma

On March 7, 1965, more than 600 nonviolent marchers were viciously assaulted when Alabama state and local police attacked the first attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery in support of voting rights. Troops on horseback chased the peaceful marchers, and many were brutally beaten by mounted police savagely swinging whips and batons, while others were trampled by horses.

“Bloody Sunday” is now an iconic moment in the legacy of the Freedom Movement. Hundreds suffered bloody beatings and some were clubbed nearly to death as police used billy clubs and tear gas to disrupt the march. Amelia Boynton, LaFayette’s closest personal ally and one of the most courageous supporters of the voting rights campaign in Selma, was severely beaten, knocked down to the asphalt and hospitalized.

Yet, LaFayette concludes his account of Bloody Sunday with a remarkable passage about how nonviolence can succeed at the very moment when it seems brutalized and beaten down. He wrote: “An objective analysis would conclude that the protesters were defeated. However, from the songs in their souls, one could hear victory.

“And victory it was, as this march, referred to as Bloody Sunday because of the bloodshed, increased the awareness of the important issue. Part of our strategy was to make the nation aware of the conditions people were suffering when they protested about their right to vote. When the national audience saw the horrors, the national conscience was awakened.”

A Nation Is Galvanized

Bloody Sunday was perhaps the bloodiest encounter of the entire civil rights movement. It shocked and galvanized a nation.

President Lyndon Johnson had already signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and then shut the door on any further civil rights legislation. Just prior to the Selma brutality, LBJ had said that he was not willing to spend any more political capital on pushing federal laws to defend voting rights.

So it is all the more remarkable that, as a direct result of Bloody Sunday, Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which ensured voting rights for black citizens and banned racial discrimination at the polls. Many analysts and historians consider the Voting Rights Act to be the most significant and powerful legislation for civil rights.

Certainly, the price was paid in full, and not only by those beaten nearly to death by Alabama police. Martyrs paid a more permanent price.

Jimmie Lee Jackson, age 26, a nonviolent protester who marched for voting rights along with his grandfather, mother and sister, was shot to death by Alabama state police in February 1965. This shocking murder of an innocent, unarmed, young man sparked the famous Selma to Montgomery March.

Immediately after Bloody Sunday, Viola Liuzzo was shot to death and Rev. James Reeb was beaten to death by white racists and Ku Klux Klan members.

The deaths ignited a nation. On March 15, 1965, only eight days after Bloody Sunday, President Johnson delivered a Special Message asking Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act. Johnson called Selma “a turning point” in humanity’s search for freedom.

Johnson said, “There, long-suffering men and women peacefully protested the denial of their rights as Americans. Many were brutally assaulted. One good man, a man of God, was killed. There is no cause for pride in what has happened in Selma. There is no cause for self-satisfaction in the long denial of equal rights of millions of Americans.”

Selma was actually an historic showdown in three acts. “Bloody Sunday” occurred on March 7, 1965, when hundreds of marchers were brutalized by police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

The second march was held only two days later on March 9. Hundreds of marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge and the entire crowd knelt down in prayer with Martin Luther King and Ralph David Abernathy in what they called a “Confrontation of Prayer.”

Many were very critical that the marchers then turned around and walked back across the bridge instead of continuing on and provoking a mass arrest. In LaFayette’s analysis, these critics didn’t understand what the real purpose of that march was.

The organizers were waiting in expectation that the federal government was on the verge of lifting an injunction against the right to march. They held the second march to keep the heat and the media glare on the city of Selma, but they wanted to avoid an unwanted, unnecessary and irrelevant battle with the federal government at a time when they were pressuring federal officials to overturn Alabama’s local laws that prevented black people from voting.

The organizers had analyzed things correctly. The federal injunction was indeed lifted only 10 days after the second march, and the third and final march was scheduled for March 21, 1965. Now the battle lines were clear. It was the Freedom Movement versus Alabama officials — from Gov. George Wallace on down to Sheriff Jim Clark — who had illegally prevented black citizens from voting for decades.

On March 21, the third March to Montgomery began in Selma and five days later, a large group of marchers reached Montgomery and held a massive rally of 25,000 people on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol.

‘How Long, Not Long’

At the culmination of the rally, Martin Luther King delivered the historic “How Long, Not Long” speech in Montgomery — fittingly, in the city where he had first become pastor of a congregation, and the site of the first significant civil rights campaign, the Montgomery bus boycott.

King asked, “How long will justice be crucified and truth bear it? I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long because truth crushed to earth will rise again.

“How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever…

“How long? Not long because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

If the Selma campaign was the best of times, it was also the worst of times. It was the best of times because as a direct result of the Selma to Montgomery marches, President Johnson and the U.S. Congress passed the Voting Rights Act and ripped up many of the Jim Crow laws that prevented black citizens from voting.

It was the worst of times because Viola Liuzzo, a civil rights activist and mother of five, was shot to death by a carload of Ku Klux Klan members as she was ferrying marchers between Montgomery and Selma after the rally. LaFayette knew Liuzzo as a selfless activist for justice.

He wrote, “There’s not a time that I drive past the monument that marks the area where she was killed that I don’t reflect on that tragic night and say a silent prayer for her and for the family she left behind.” [In Peace and Freedom, p. 141.]

LaFayette says he has “mixed emotions” whenever he thinks about Liuzzo and all those who gave their lives so selflessly for the cause of justice, yet he always remembers “how she sacrificed her life to that others might live and enjoy freedom and democracy in their own nation.”

Those words are a testament as to how we should remember and honor those who gave their lives to win one of the most important struggles in our nation’s history.

We must remember Medgar Evers, Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo, Rev. James Reeb, Martin Luther King Jr. and the four girls killed in Birmingham, Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley.

I remember, now and always, how an oppressed and insulted people, a people subjected to a nearly totalitarian system of racism enforced by overwhelming levels of state-sanctioned violence, found the courage to march on with all the odds against them, march on despite the beatings and bombings and bloodshed, march on despite the murders. They refused to let truth be crushed, and justice crucified.