by David Solnit

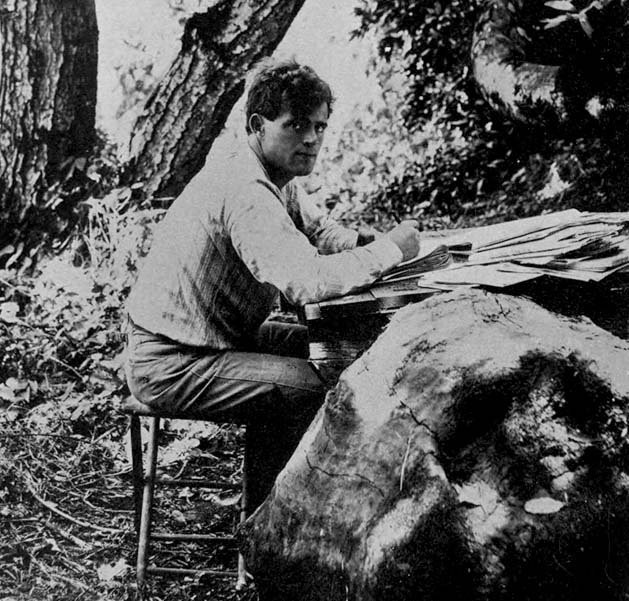

[dropcap]N[/dropcap]o, he’s not just the dog story and survival-adventure writer of Call of the Wild and The Sea-Wolf. Jack London’s The Iron Heel is the strongest articulation of London’s emerging anti-capitalism and may have been the first dystopian-utopian science fiction novel.

Written in 1907, the novel predicted the first World War (though with a different outcome), and the merger of corporate power with authoritarian government seen in fascist governments in the 1930s and 1940s and today in the escalating concentration of power and wealth in our current corporate capitalism.

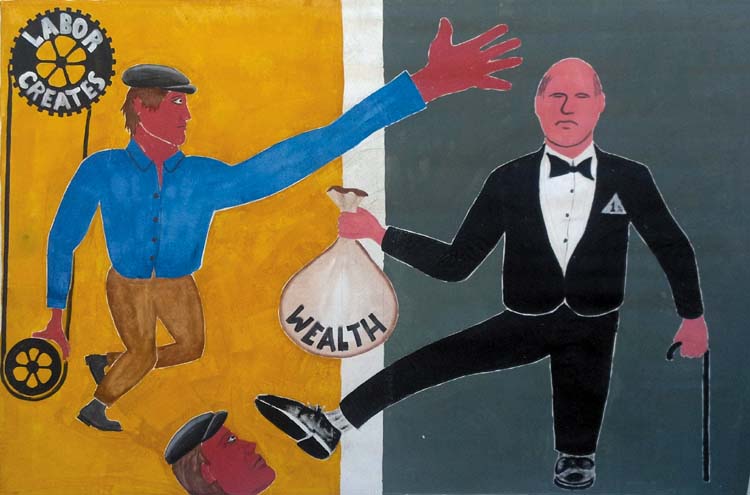

Much of it reads like it could be today, which is why a group of community artists, activists and organizers — the Iron Heel Theater Collective — have chosen to bring it to life using puppetry, painted picture-story cantastoria banners, readers theater and live music.

The first performance on May 18 played to an enthusiastic full house at the Hillside Community Church in El Cerrito and benefited TeamRichmond.net — the progressive candidates for Richmond City Council and Mayor (candidate Eduardo Martinez is the lead performer of the readers theater performers).

Richmond progressives and ordinary folks are battling against Chevron, Wall Street banks, the realty industry, building trades unions, and other parts of the local power establishment that are spending millions and fighting hard to return Richmond — the most progressive city in the United States — to being a company town.

The next performance is scheduled for the evening of October 31, 2014, as part of the Jack London Society Biennial Symposium to be held in Berkeley.

I met Tarnel Abbott over the last decade working on mobilizations against the Chevron Richmond Refinery and with the election campaigns of the Richmond Progressive Alliance, who put an end to the 100-year rule of Chevron in its former company town, Richmond, Calif. Tarnel is a straight-talking retired member of SEIU Local 1021 (used to be 790).

The former Richmond librarian was awarded by the California Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Committee the 2006 Zoia Horn Intellectual Freedom Award for her tireless advocacy of free speech. She is also Jack London’s great-granddaughter and continues, as her father did, London radical activism.

Tarnel was invited to perform from her great grandpa’s The Iron Heel and her own writing on the Occupy movement at the Ankara Theater Festival in 2012 and again this year, with Richmond artist Regina Gilligan. I assisted Tarnel and Regina this year, sharing puppetry and cantastoria-making skills, creating a “cantastoria” or picture-story-painted-banner series and slightly larger-than-life masks, which they took to Ankara, Turkey.

“Cantastoria,” in the words of leading U.S. cantastoria maker-performer Clare Dolan, “is an Italian word for the ancient performance form of picture-story recitation, which involves sung narration accompanied by reference to painted banners, scrolls, or placards. It is a tradition belonging to the underdog, to chronically itinerant people of low social status, yet also inextricably linked to the sacred.

“It is a practice very much alive today, existing in a wide variety of incarnations around the world, and fulfilling very diverse functions for different populations. Picture-story recitation in its earliest form involved the display of representational paintings accompanied by sung narration. Originating in 6th century India, this religious and then increasingly secular practice evolved as it spread both east and west.”

Jack London described writing The Iron Heel in a letter to a friend in 1908, calling it “a novel that is an attack upon the bourgeoisie and all that the bourgeoisie stands for. It will not make me any friends … am having the time of my life writing the story.”

Jonah Raskin, author of The Radical Jack London, wrote: “It was not until the coming of the First World War that it began to attract readers and to win London admiration for his prescience. Indeed, only when socialists in France went to war against their socialist brothers in Germany, and when the rallying cry of ‘international solidarity’ fell on deaf ears, did The Iron Heel attract an international following. The rise of Hitler and Mussolini solidified London’s reputation as a ‘sociological seer.’ In Trotsky’s eyes, he was a genuine ‘revolutionary artist,’ and far more perceptive than either Rosa Luxemburg, the early twentieth-century German revolutionary, or V. I. Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, who admired London and seems to have borrowed the phrase ‘the aristocracy of labor’ from The Iron Heel to describe that sector of the working class that had lost its working-class consciousness and sided with capital. In the 1960s, The Iron Heel experienced another resurgence. Vietnamese as well as Americans read it as a text on the evils of imperialism. It has never gone out of print, but London scholars often ignore it.”

Here is my favorite passage from our theater adaptation of The Iron Heel where anti-capitalist organizer Ernest directly confronts Wickson, a leader of the 1% capitalist elite:

ERNEST: “With modern technology, five people can produce bread for a thousand. One person can produce cotton cloth for two hundred and fifty people, woolens for three hundred, and boots and shoes for a thousand. If modern worker’s producing power is a thousand times greater than that of the cave-man, why then, in the United States today, are there millions of people who are not properly sheltered and properly fed? The capitalist class has mismanaged. You have made a shambles of civilization. You have been blind and greedy. You are fat with power and possession, drunken with success.

“Now, let me tell you about the revolution. Such an army of revolution, millions strong, is a thing to make ruling classes pause and consider. The cry of this army is: ‘No quarter.’ We will be content with nothing less than all that you possess. We want in our hands the reins of power and the destiny of mankind. We are going to take your governments and your palaces…and then you shall work for your bread even as the peasant in the field. Here are our hands. They are strong hands!

“This is the revolution, my masters. Stop it if you can. You have criminally and selfishly mismanaged. And on this count you cannot answer me here to-night!… You cannot answer.”

WICKSON: “No answer is necessary! Believe me, the situation is serious. That bear reached out his paws tonight to crush us. He has said that it is their intention to take away from us our governments and our palaces. A great change is coming in society; but, haply, it may not be the change the bear anticipates. The bear has said that he will crush us. What if we crush the bear? We are in power. Nobody will deny it. By virtue of that power we shall remain in power.

“We will grind you revolutionists down under our heel, and we shall walk upon your faces. The world is ours, we are its lords, and ours it shall remain. Labor has been in the dirt since history began. And in the dirt it shall remain so long as I and mine and those that come after us have the power. There is the word. It is the king of words — Power. Pour it over your tongue till it tingles with it. Power.”

ERNEST: “It is the only answer that could be given. Power. We know well by bitter experience, that no appeal for the right, for justice, for humanity, can ever touch you. Your hearts are hard as your heels with which you tread upon the faces of the poor. You cannot escape us. Power will be the arbiter, as it always has been. It is a struggle of classes.”