The off-leash glory of the Albany Bulb

Albany, California was founded on a dispute over a garbage dump. At the beginning of the 20th century, what is now Albany was an unincorporated tract of Alameda County known as Ocean View. For years, the little community’s southern neighbors mostly saw it as a convenient place to dump trash, which piled up at the base of what’s now called Albany Hill. In 1908, Ocean View decided it was time for a change. Swelling with aggrieved civic pride, its residents resolved to drive out the dumpers by any means necessary. Initially, the men satisfied themselves by intoning threats and flashing pistols at Berkeley garbagemen. But before long, shotgun-toting women were driving off horse-drawn rubbish carts, shouting “S’help me Jolly Roger!”

Local newspapers published frenzied reports of garbage “riots” as crowds “armed with broomsticks, stove-pokers, clubs, and such menacing weapons” enforced a red line. No more would trash created in distant Oakland and Berkeley pile up at the foot of the hill. Further driven by the garbage controversy, the people of Ocean View rejected annexation by Berkeley and incorporated as an independent city later that year (the name of the new town was changed to Albany in 1909 to avoid confusion with the other “Ocean Views” that littered California, including nearby districts in Berkeley and San Francisco).

But newborn Albany’s dreams of a tidier future were soon dashed. The foreign trash piles that had offended Ocean Viewers enough to take up arms were now theirs alone; their now-sovereign garbage heaps were still garbage heaps. As the town of Albany grew, so did the dump by Albany Hill, which began pushing its way further and further into the bay. By the late 1950s, the situation had become a crisis.

“There’s simply not enough land,” city officials declared in 1957, “We have the choice of closing the dump or doing something about it.” So they did something about it.

In 1963, the City of Albany contracted the Catellus Corporation, a subsidiary of the Santa Fe Railroad Company, to create a massive landfill at the dump. Industrial debris from nearby demolition sites would be pushed into the bay pell-mell, expanding the dump and creating “usable land” in the process. The Bay Area had no shortage of massive demolition projects in the 1960s, as “urban renewal” slum clearances and BART construction reshaped the landscape. Debris came from all over, and piles of concrete, rebar, scrap iron, plastic, and other industrial waste soon stretched into the water for a mile. Piling up countless tons of industrial refuse in the fragile ecosystems of the San Francisco Bay may sound shortsighted, but Albany’s rulers had a vision. They had seen the writing on the wall: the wild west era of dumping was drawing to a close.

Though it may be hard to imagine now, the East Bay shoreline was once a string of dumpsites. Where Cesar Chavez Park and Point Isabel now stand were great mounds of trash, residential and industrial. Fires burned constantly, spewing pollutants into the air and leeching poison into the earth and water. As Berkeley’s beloved troublemaking poet Malvina Reynolds sang: “Seventy miles of wind and spray / Seventy miles of water / Seventy miles of open bay / It’s a garbage dump.”

In 1961, three forward-thinking members of the East Bay elite—Sylvia McLaughlin, Catherine Kerr, and Esther Gulick—looked down on the gathering wreckage from their Berkeley Hills living rooms and decided something would have to be done to protect their million dollar views. These women set out to save the bay, forming a new organization: Save the Bay.

Save the Bay’s founders were all married to prominent figures at the University of California, ensuring them access to the rarefied circles of media and policymakers. Catherine “Kay” Kerr’s husband, Clark, was the president of the UC (it would still be a few years until Ronald Reagan would fire him for his insufficient brutality towards student activists). Esther Gulick was married to a prominent left-liberal economics professor. The group’s driving force, Sylvia McLaughlin, was married to Donald H. McLaughlin, a UC Regent and CEO of the Homestake Mining Company. Best known for operating the world’s largest gold mine in the Lakota Sioux’s sacred Black Hills, in the years that Save the Bay was getting off the ground, Homestake was also one of the leading millers of yellowcake uranium for use in nuclear weapons.

While Sylvia’s legacy is enshrined by the edenic park and wildlife refuge that now defines the East Bay shoreline (McLaughlin Eastshore State Park), her husband Donald’s lives on in a constellation of Superfund sites dotting the western states, including a zone of elevated cancer rates near old uranium mills in New Mexico that locals refer to as the “Death Map.”

That a committed environmentalist like McLaughlin would fund her campaign to protect the ecosystems in her own backyard with the profits of her husband’s ecological violence elsewhere is less of a contradiction than it may appear. Until the late 1960s, organized environmentalism was a solidly bourgeois affair, as particularly sensitive members of the capitalist class sought to ameliorate the more unsightly consequences of their own actions. Save the Bay was no exception to this rule.

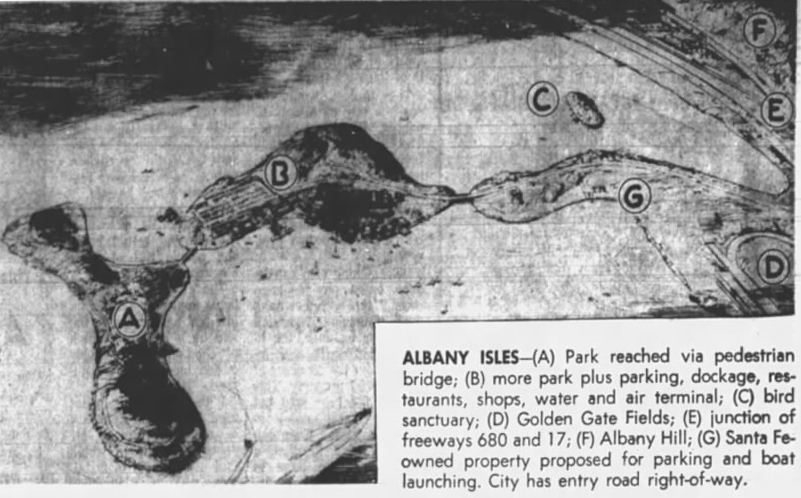

With Save the Bay’s efforts along the East Bay shoreline rapidly gaining steam, Albany’s city fathers dreamed up a new future for their dump. The “usable land” created by Catellus’s landfill would expand into a 98-acre chain of man-made islands. These islands would boast “seven seaside view restaurants and specialty shops,” a museum, and a floating hotel (or “boatel”). Developers would ship in white sand to build “San Castle Beach”—a name that took the California tradition of faux-Spanish toponyms past the point of absurdity. This luxury “oasis” would be called Albany Isles. When the state passed conservationist legislation promoted by Save the Bay, Albany won a special carve-out for the Isles project.

Despite this initial victory, the Isles plan soon floundered. Jurisdictional disputes between the city, the state, private developers, and Catellus—who continued to operate the Albany Dump on the site—slowed the project to a crawl, forcing numerous revisions. After a few more attempts to get it off the ground, Albany Isles was declared dead in the mid-1970s. The landfill’s odd shape—a long, thin “neck” leading into a fat, round “bulb”—is a lasting monument to the aborted Isles plan. Around the same time, the state swooped in to shutter the dump on environmental grounds, asserting that “debris is piled up as high as a four-story building and may have done irreparable damage.” Residents and businesses continued regular dumping at the site for another decade, until the City of Albany finally fenced it off in 1983. Into the 90s, the old dump sat neglected. Public opinion was unanimous that it was little more than an eyesore slowly leaking toxic pollutants into the bay.

Quietly, gradually, nature reclaimed the landfill. Pampas grass covered the rebar and rabbits began to frolic among the concrete. A 1995 study commissioned by the city counted dozens of species of plants and animals, finding that in “the decade since the landfill was closed, a great variety of vegetation, both native and exotic…has sprung up, covering discarded remnants of old roadways and castoff remains of demolished buildings. Small animals live in the ‘ruins.’ Wetland plants are taking hold along the shore, foretelling a growing shorebird population.” Amid this blooming biodiversity, a new human community would soon take its place on the landfill.

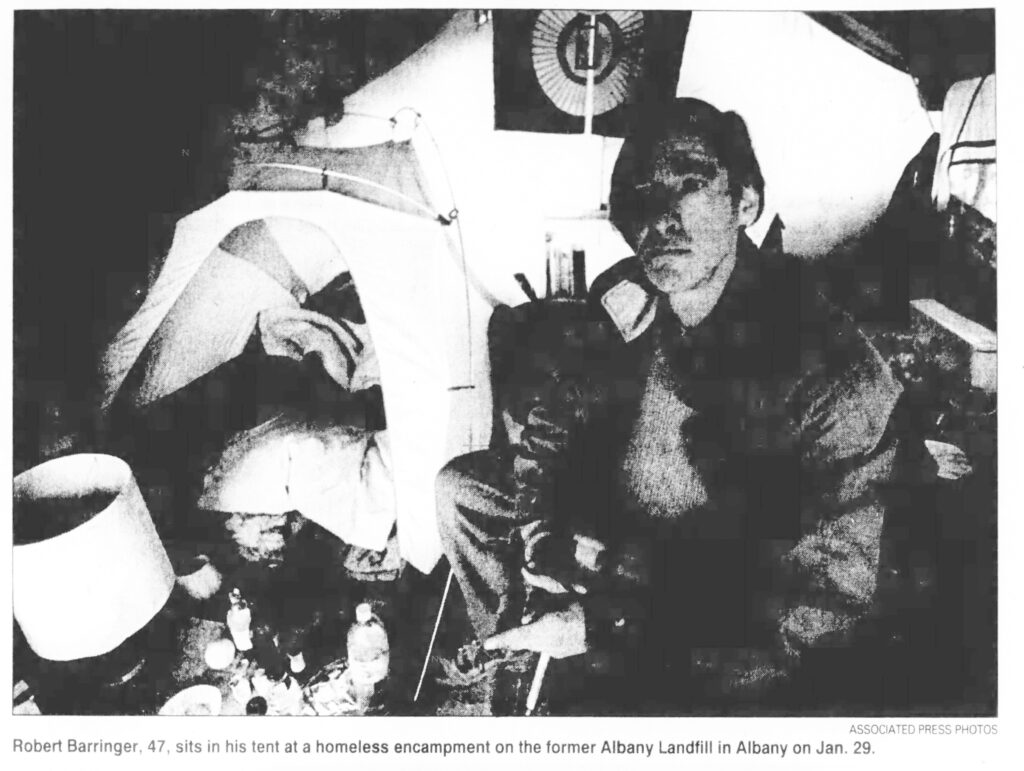

Robert “Rabbit” Barringer, Bulb resident and narrator of Bum’s Paradise (2002). Associated Press, February 14, 1999.

In 1994, a small group of environmentalist anarchists from Oakland set up camp on the Albany dump, living there on-and-off for the next few years. Whether they intended to blaze a trail or not, by the end of the decade they were joined by some two dozen others, as people fleeing anti-homeless “crackdowns” in Berkeley and other parts of the East Bay found their way to the landfill. Encampments were being rousted everywhere from the railroad tracks to Telegraph Avenue, and cops began shuffling their residents to the dump where they would be out of both sight and mind.

The squatters developed a fierce loyalty to the landfill. They built semi-permanent structures—some equipped with showers, television sets, and fully functional kitchens. A “Landfillian” identity developed, as unhoused people found a sense of security, belonging, and independence they felt they had been denied elsewhere.

“Never have I experienced such a powerful sense of community,” declared Landfillian Robert “Rabbit” Barringer. He added that, though the scene was never totally untroubled by violence, drugs, or theft, the community quickly “established codes of protocol in order to maintain a sense of security.” There was no question: the dump was safer than the streets. Another resident, Ashby Dancer, described his neighbors in Bum’s Paradise (2002), a documentary narrated and partially filmed by Barringer: “They’re all insane! But they’re all good people.”

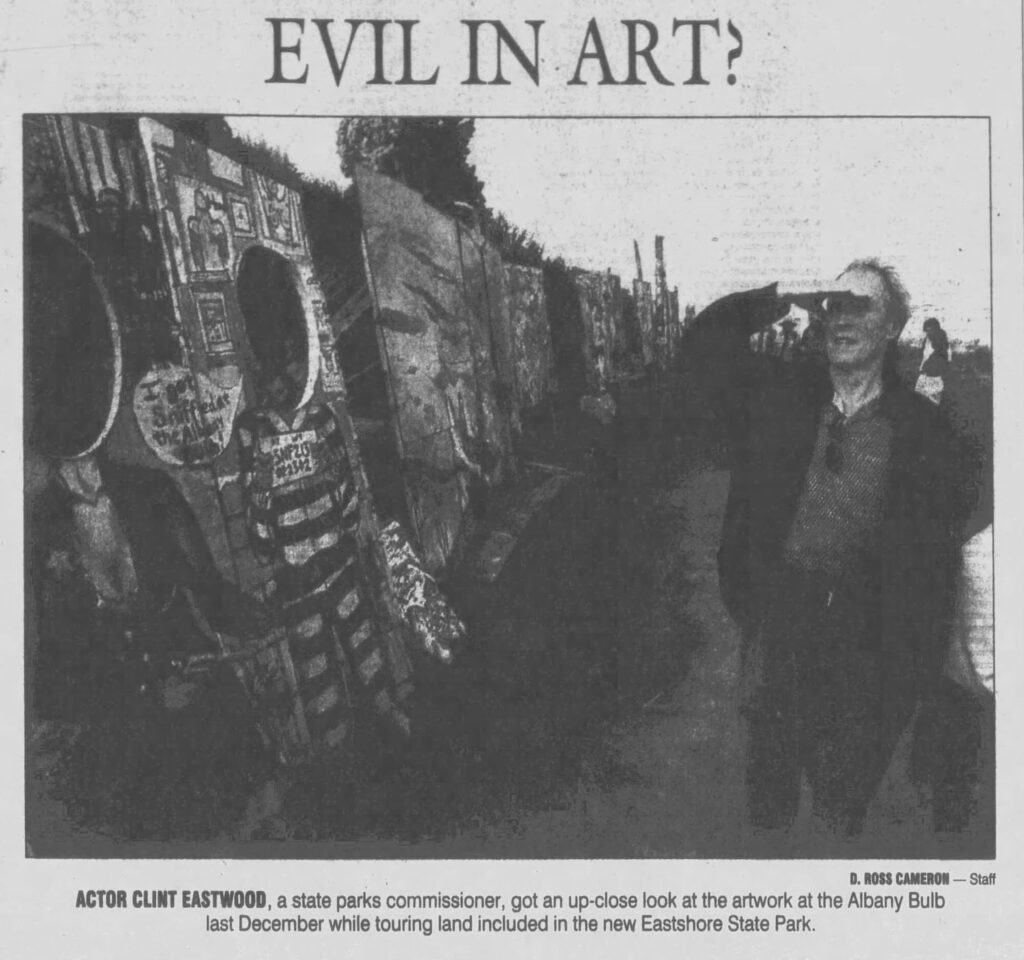

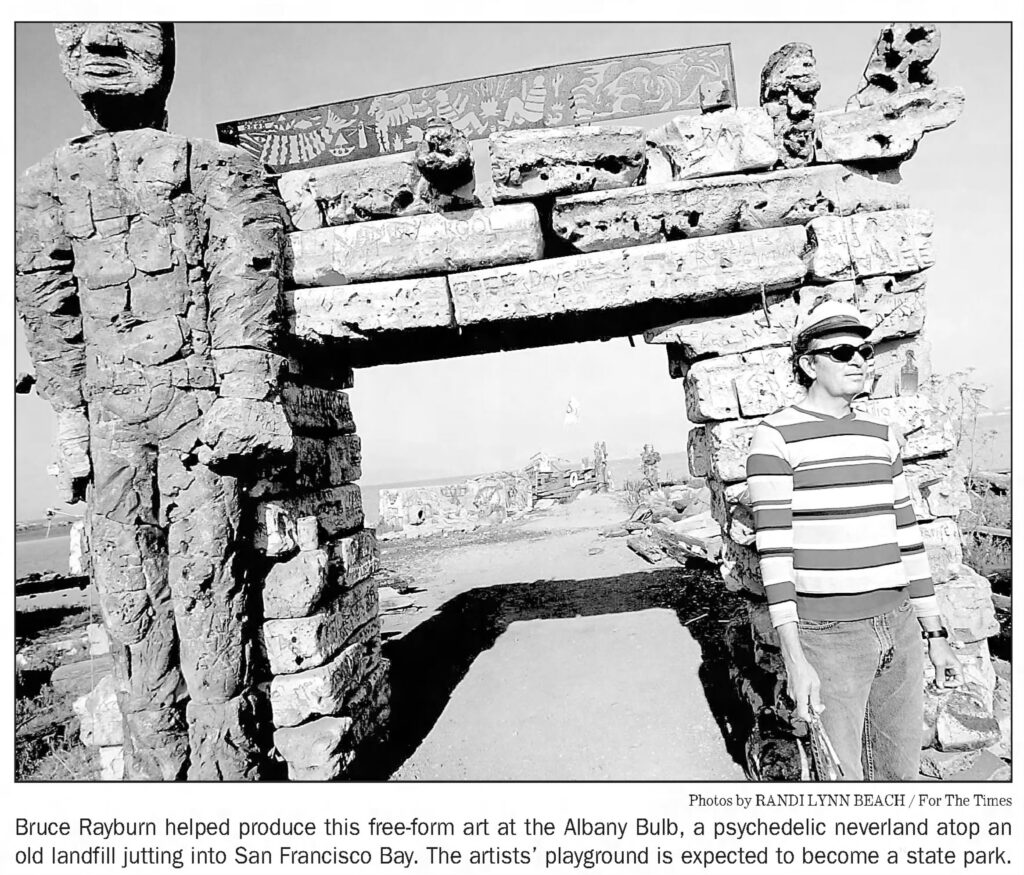

As the homeless community reached its peak, a second group arrived on the landfill, which locals began calling “the Bulb.” The artist collective SNIFF—painters Scott Hewitt, Scott Meadows, Bruce Rayburn, and David Ryan—took to creating large, colorful, wildly imaginative murals on the chunks of industrial refuse in 1998. SNIFF was soon joined by Berkeley fixture Osha Neumann, veteran of the wild 1960s bohemian-anarchist group Up Against the Wall Motherfucker and a prominent legal advocate for the rights of the homeless. The crusading lawyer-muralist’s far-out sculptures and oversized human figures blended easily with SNIFF’s eclectic, madcap sensibility as well as the colorful chaos of the Bulb’s full-time residential community. In fact, no clear line separated the artists from the residents. Homeless artists such as “Picasso Mike” followed SNIFF’s lead in treating the concrete and rubble as a canvas. Many Bulb denizens turned their makeshift shelters into works of art, like “Mad Marc’s Castle,” a landmark which still stands today. Together, the so-called homeless community—as many would point out, the Bulb was their home—and the artists turned the landfill into a free space for experimental self-expression.

Just as the “Free Sector of Albany” was beginning to establish itself on the landfill, the city completed work on the Albany Waterfront Trail, bringing joggers, birdwatchers, and picnickers into this once marginal, out-of-the-way place. Complaints about the homeless, mostly aesthetic in nature, flooded into the city government, and in March 1999, Albany City Council passed an anti-camping ordinance.

By June, in the name of “public safety,” they blanketed the landfill with eviction notices. Bulb residents marched to Albany City Hall to plead their case before city council. The legality of the (pre-Grant’s Pass decision) anti-camping ordinance was dubious. With zero shelters or other accommodation, there was nowhere an unhoused person could legally sleep in Albany. Even if the Landfillians—who chose life on the Bulb for its freedom, openness, natural beauty, and distance from civilization—could be enticed by the grim trailers the city had moved into the Golden Gate Fields parking lot, those trailers were meant to be temporary, anyway. But as Osha Neumann writes, “They were not on the landfill because of their skills at organizing themselves or anyone else.”

Ultimately, the police successfully harried the community out of “bum’s paradise.” Some took up residence on an abandoned gun range, where they hoisted the camouflage flag that had once flown over the Bulb. Mostly they scattered in different directions. Fifteen years later, almost all were still homeless.

While the Bulb’s full-time residents waged their lonely fight to keep their collective home, another fight over the landfill’s future was heating up. In the years since the early 1960s, Save the Bay had been joined by the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and the umbrella group Citizens for the Eastshore State Park (CESP) in their fight (against dump operators, developers, and boosterist city officials) to establish a park stretching from Emeryville to the Carquinez Strait. By the late 90s, they had substantially succeeded. After decades of abuse and misuse, large parts of the Emeryville and Berkeley waterfronts, the Albany mudflats, and more were being transformed into a new state park, into which the Bulb was slated to be absorbed. The CESP plan called for massive restrictions on recreational access in the park, envisioning a future for the landfill with a bare minimum of human involvement.

At the same time, there were many who had come to love the Bulb for its strange beauty and the environment of cultural freedom fostered by its overlapping residential and artistic communities. No group was more appreciative of the status quo than advocates of off-leash dogs. Arguing that protecting biodiversity and free human activity were not mutually exclusive, a motley coalition of anti-leash dog owners and underground artists formed the pressure group Let It Be. Their slogan: “We Support Off-Leash Dogs and Art and We Vote!”

This unruly new organization had good reason to worry about the future of art on the Bulb. Eastshore State Park had already spelled the end of another venerable tradition of East Bay public art. For decades, ever-changing driftwood sculptures had populated the Emeryville mudflats, just visible from the interstate leading into San Francisco. Such anarchic human intervention in the landscape was incompatible with the conservationist vision of CESP. By 1999, the driftwood sculptures were gone. Unsurprisingly, the middle-class environmentalists who had done so much genuinely valuable work to protect the shore met the artists and dog lovers of Let It Be with open disdain. No compromise was reached. The more respectable CESP program prevailed, defeating Let It Be’s proposals for free dogs, art, and people. Or at least, it prevailed on paper.

In reality, the artists of the Bulb carried on much as they had before. Despite occasional—and sometimes quite spectacular—crackdowns, paintings, sculptures, and installations kept popping up. The renegade raves continued. A skate park appeared. City signs exhorting park visitors to “Please Keep All Dogs On-Leash” were removed and re-bolted upside down. Soon even the homeless community began returning. By the end of the 2000s, many of the Bulb’s long-time residents had re-established themselves, along with a number of newcomers, among them victims of the 2008 financial crash and anti-homeless sweeps in other parts of the Bay Area. They had sunk deep roots at the landfill, and time had proven there was nowhere else many of them would rather be. As one long-term resident put it: “If they knew how pimp we were, they wouldn’t let us be here. ‘They’re not suffering? Fuck it man, get ‘em out of there… You’re homeless! Get homeless!’” adding, “They couldn’t give me a home as homey as my home out here, homie.”

The City of Albany didn’t fully surrender. They continued to make their presence known, sending in police and other city workers to remove the odd artwork or harass the odd person. Finally, in 2014, city officials determined to make another, final push to clear out the Bulb’s 70-or-so full-timers. The eviction notices returned. This time, the Landfillians were considerably more organized.

Making a real effort to reach out to the general public, they formed their own advocacy group, Share the Bulb. They had a website. They distributed flyers. They produced a documentary about themselves and their struggles, Where Do You Go When it Rains? (2014). They held meetings and published articles. They filed a lawsuit against the City of Albany. Bulb resident Katherine “K.C.” Cody spoke eloquently before the city council, explaining that “the uncontrolled population growth [on the landfill], human and canine, is a result of other camps being evicted: behind the Seabreeze in Berkeley, under the freeway and Central Avenue… the refugees from People’s Park. Though the words ‘go to the Bulb’ were never said, the implication was: go to the Bulb. Got to stay away from People’s Park? Go to the Bulb.” In the end, the city was unmoved. In exchange for a one-time payment of $3,000, the bulk of the landfill’s residents agreed to vacate the Bulb, promise to “stay away” from public land near the waterfront for a year, and forfeit their right to access certain housing assistance programs. Some remained committed to life at the landfill and refused to go. Once again, police closed in, the Bulb was raided, and its citizens dispersed. This time it stuck.

Two years after the Bulb’s impressively strong-willed community was finally evicted, a UC Berkeley urban planner formed a non-profit, Love the Bulb, with the goal of “preserving the creative spirit” of the landfill. Past advocates’ failure to win a coherent victory notwithstanding, the Albany Bulb remains substantially unleashed. Both dogs and art still roam free. And despite the violent removal of the community that undoubtedly cherished it most, the landfill is considerably more of an oasis than the promoters of Albany Isles ever imagined. At the impossibly poetic intersection of pristine natural beauty and industrial disaster, the Bulb is the Bay Area’s most democratic arts space. The East Bay Regional Parks District interferes sporadically, roping off the occasional artwork with caution tape and removing it for “safety and accessibility.” But censoriousness of this kind is the exception rather than the rule. The Bulb currently appears to be in a state of détente, but major questions continue to loom about its future. A conflict may be inevitable. It is worth fighting to keep the leash off.

Matt Ray and Matthew Wranovics are the founders of Left in the Bay, a project that uncovers and retells stories of social struggle in the San Francisco Bay Area. Follow them on social media @leftinthebay.