‘We were the Landfillians…That word is not in the dictionary, but I started putting it in my poems.’

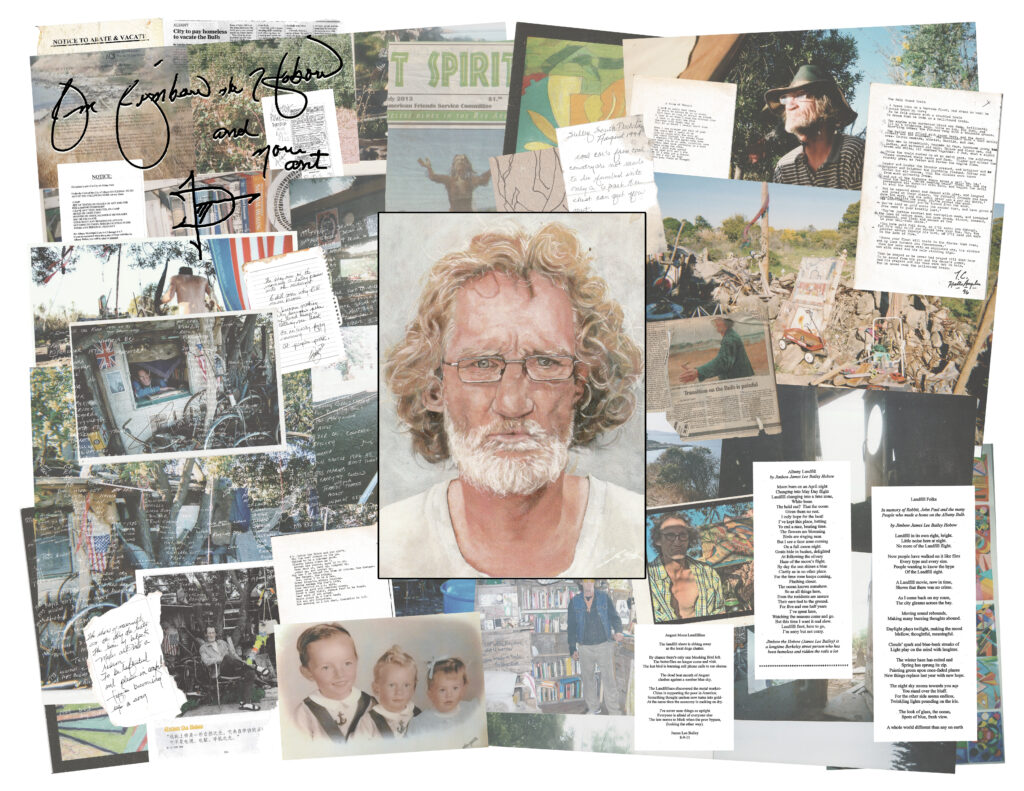

Jimbow the Hobow—born James Lee Bailey—is a hobo, poet, artist, and archivist who first made a home on the Albany Bulb in 1997. He’s a cancer survivor, has been arrested at least 100 times, his nose has been broken on 33 different occasions, and according to the highly detailed catalogue of photographs, handwritten notes, and poetry he keeps in his apartment along the Alameda waterfront, Jimbow has cheated death as many times as there are days in a year.

Born December 20, 1953 to Pentecostal tobacco farmers in southern Ohio, Jimbow entered the world with a crossed eyed, a cleft lip, and soon learned to write left-handed, all of which convinced his mother he was a spawn of the devil. Jimbow describes his early life on the tobacco farm as a time of neglect and abuse, in which he was fed different food than his siblings, was often left to forage and build fire outside in the cold, and was subject to recurring acts of violence perpetrated by his mother, father, and older brother. Jimbow credits his grandmother with teaching him how to bathe and dress himself, and recounts the town’s attempts to intervene in his family’s abuses as futile and combative.

“The preacher came to tell [my mother] to take better care of me and she cussed him out,” Jimbow told Street Spirit, “she even swung at him a couple times. It was a southern hillbilly thing. You don’t talk about the family outside of the family. That was the code.”

At the age of 16, Jimbow ran away with the circus. He joined Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey as an animal caretaker, which traveled the country by train on both a “Blue Tour” and “Red Tour”—two different editions of the three-ring circus production that would rotate every two years.

“I took care of the elephants for the Blue show and the [Shetland ponies] for the Red show,” Jimbow said, “I took care of all types of horses, even a llama. I was a farmer, I liked animals.”

In 1970, Jimbow’s railroad travel brought him to Berkeley for the first time, where the burgeoning, countercultural hippie scene quickly became an anchor point between seasonal circus work and time served behind bars. In 1974, Jimbow was arrested on charges of grand larceny and burglary for stealing $100 from a liquor store cash register. Convicted just 20 days later, he served an 18-month sentence inside the historic Mansfield Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio.

“I didn’t have any visits or any money coming in,” Jimbow said, noting that his family’s farm was located just a few hours away from the prison, “and I was nearly beat to death in there. I still walked out, but nobody was there to help me. I started to grow paranoid that way.”

This paranoia began to influence how Jimbow interacted with people at large. As the formidable experiences of childhood and incarceration pushed him further to the fringes of American life, he developed his own code of participation in the society he felt had rejected him.

“Every time I go to the store, it’s like someone is gonna watch me. So I stopped going into stores, stopped eating in restaurants. I’ve never owned a suit, don’t know what champagne tastes like. I’ve never had a driver’s license, a credit card…I don’t even have Wi-Fi,” he said.

Through the late 1970s and into the 80s, Jimbow’s continued nomadism transformed into the life of an iconoclastic American vagabond. Between visits to his community around People’s Park and traveling with the Rainbow Family of Living Light—known for their annual Rainbow Gatherings—Jimbow met his friend and mentor Caveman, who taught him “how to survive on the street” and “catch trains without making any mistakes.” Caveman soon introduced Jimbow to “The Wrecking Crew,” a national network of freight-riding hobos that formed as an alternative to another group of rail riders at the time, the Freight Train Riders of America (FTRA).

“[FTRA] wore black, with black bandanas,” Jimbow said, “and Wrecking Crew wore blue bandanas. We basically got along, but didn’t hang out with each other. Caveman knew a lot of people, but didn’t associate with [FTRA]. They were disrespectful to women, and much more violent. I was a guy who wanted to learn something different, and wanted to make sure I was safe when I jumped on [a train], so I teamed up with Wrecking Crew.”

Jimbow’s travels with The Wrecking Crew took him to train yards across the United States, Mexico, and Canada, where he and his fellow riders would disembark and head into town. While the crew’s prowl through town was usually in search of more alcohol, what they often found at the bottom of their wine jugs was trouble.

“We tore up every cheap hotel that ever existed, would rent a room once a month to shower with our clothes on so we wouldn’t have to do laundry,” Jimbow said, “So when [hotels] learned the color of [Wrecking Crew] rags, they wouldn’t rent to us anymore.”

Jimbow recounts once walking 15 miles to the Fresno railyard after accidently boarding a freight car that was left out on a spur in the scorching valley heat, a mistake he never made again. Once in Salt Lake City, after a night of hard drinking at the Dead Goat Saloon, he found himself on the third story of a nearby abandoned building.

“I’m standing on the floor with a fifth of Jim Beam in my hand,” Jimbow said, “and all of a sudden there was no floor.”

Jimbow had fallen thirty feet down an elevator shaft but miraculously walked away unscathed, the bottle still clutched in his palm.

“They took me in for an x-ray and nothing was broken. Like I had missed every pipe…We were crazy,” Jimbow said, “What can I say, we were winos back then.”

Jimbow has no qualms talking about his relationship to alcohol, which started to take a darker turn during his time with The Wrecking Crew.

“Gallo started making these ‘pharmaceutical wines,’ Thunderbird…Night Train. It didn’t have no grapes, it was like alcohol and embalming fluid. And we all got addicted to it, it was cheap. That drug got into our culture throughout that era. It was like the opioid epidemic.”

Through the 1980s, Jimbow would often make his way back to People’s Park between stints riding the rails, where another epidemic was just beginning to take shape on the streets of the Southside neighborhood—the use of crack cocaine.

“When crack cocaine hit the streets, it changed everything,” Jimbow said, “everything started to fall apart. People started robbing each other, killing each other. My best friend and his dog were killed underneath Strawberry Creek Bridge for his Social Security money. Crack users started dominating areas where free food and clothes were coming in. It broke the community into little pieces.”

In 1988, after a large sweep of the area surrounding People’s Park, Jimbow joined a growing number of vagabonds who had drifted down to the railroad tracks north of Gilman Street in West Berkeley, where Target now stands along the Eastshore Highway. For close to a decade, Jimbow would intermittently set up camps then catch outgoing freight trains close to Albany Hill. He stayed in close contact with his dear friend Osha Neumann who would store his possessions while he was out riding the rails, and Jimbow often sent correspondences back to Berkeley from various jails and motel rooms. On many occasions, Neumann posted Jimbow’s bail after he was picked up for vagrancy or alcohol-related offenses.

“I’d just be cooking my breakfast by the tracks and they’d pick me up because I had a beer,” Jimbow said, “This was the case all over the place. So I’d have to call my friend Mr. Neumann and he’d bail me out of jail.”

Jimbow would often return to the East Bay between run-ins with the law, referring to Berkeley as the “penny in [his] pocket” when life on the rails got too rough. But by 1997, as Caltrans began construction on the Interstate 80 interchange, both Albany and Berkeley police began targeting the community that had been growing in the “jungles” along the east side of the tracks, suggesting they move onto the nearby landfill.

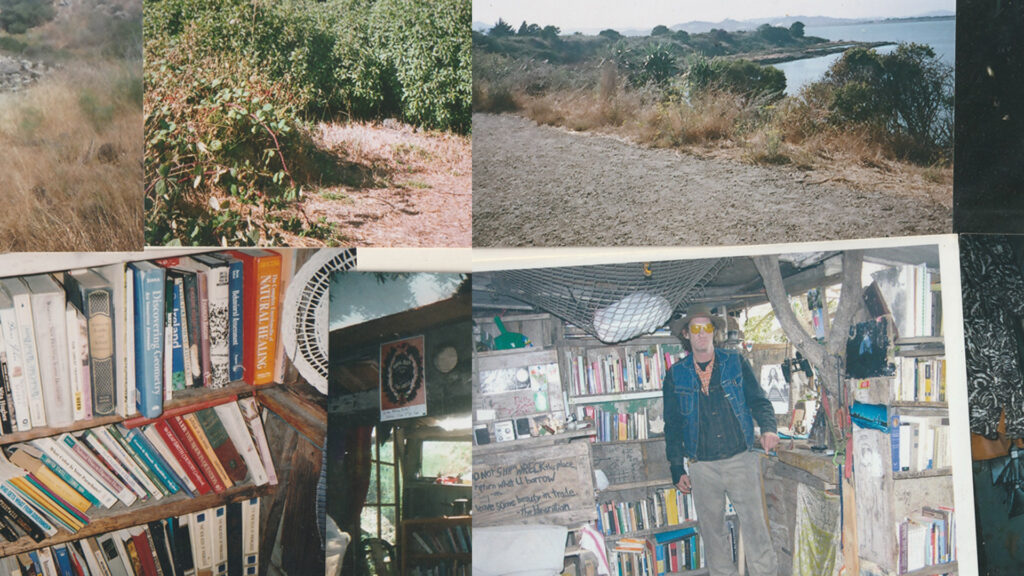

Thus began Jimbow’s life on the Albany Bulb, a move he describes as a moment of “retreat.” As time wore on, a community of fellow vagabonds and artists began to grow beneath the coyote bush that dotted the Class III landfill, which inspired Jimbow to pursue a creative process of his own—poetry.

“We were the Landfillians,” Jimbow said, “That word is not in the dictionary, but I started putting it in my poems.”

Jimbow had started writing poetry at the age of 18, but it wasn’t until his residency at the Bulb that he found his voice through verse. Encouraged by Osha Neumann—who was spending time at the Bulb making art of his own—Jimbow developed a daily writing practice that helped him make sense of his rough and tumble life, a journey of self-discovery, acceptance, and tranquility that was further inspired by the wild, unregulated ecosystems taking root among the Bulb’s endless piles of construction debris.

“[Neumann] says, ‘you know what, you don’t need toknow how to spell,’” Jimbow recounted in the 2002 documentary film Bum’s Paradise, “Just put it down and come back to it in a couple days and put it back together. And I did that, I took his advice. Now I can sit down all day long and write anything I want. This has really inspired me a lot.”

Jimbow soon built a home for himself on the Bulb’s northern flank, a one-room house made from landfill-foraged wood, scrap metal, and glass, complete with windows and a door. While there’s disagreement among the Landfillians as to how the story goes, Jimbow’s home was under threat of demolition sometime in the early 2000s, one of countless attempts by the City of Albany to clear the landfill of encampments. Away from the Bulb at the time, Jimbow had left his home under the care of his friend and fellow Landfillian Andy Wellspring, who was told by city officials that art installations would be preserved through the sweep. Quick on their toes, Wellspring had an idea—convert Jimbow’s home into a library. While Jimbow still used it as his living quarters once he returned to the landfill, the walls of his house were soon lined with shelving, chairs, and countless books. He named it Freeman’s Library, after an unhoused person who had recently been killed while incarcerated inside Santa Rita Jail.

Around 2012, as a steady influx of new residents began establishing camps on the Bulb, the Freeman Library was set on fire by an unruly resident and never fully restored. But after years as the landfill’s resident librarian, Jimbow has cultivated a deep respect for the art of the archive. At his current home in Alameda, among countless binders, briefcases, and baskets filled with photographs, newspaper clippings, and handwritten poetry, Jimbow also managed to salvage the library’s ledger, which includes hundreds of signatures and notes left by library visitors over the years.

In the aftermath of the Bulb’s final eviction in April 2014, Jimbow—then 60 years old—sought housing services instead of catching the next outbound train. For the next eight years, he lived between hotel rooms and transitional housing in both downtown and East Oakland before securing a housing voucher in Alameda during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jimbow continued writing through the years spent in transitional housing, but felt the flame burn out during the height of the COVID-19 lockdown, a period that “left him in solitude.” But as time passed, he has steadily begun his writing practice again, crediting his memories and experiences living on the Bulb as a driving force behind his creative output.

“For 47 years, I walked around with nothing but hate,” Jimbow said, “I tried to kill myself 5 to 8 times. I was traumatized…by my family, by the whole ball of wax. But then I found the Bulb. I started writing. Nature [on the Bulb] played a huge part in helping me find myself. That’s when it all came to a head.”

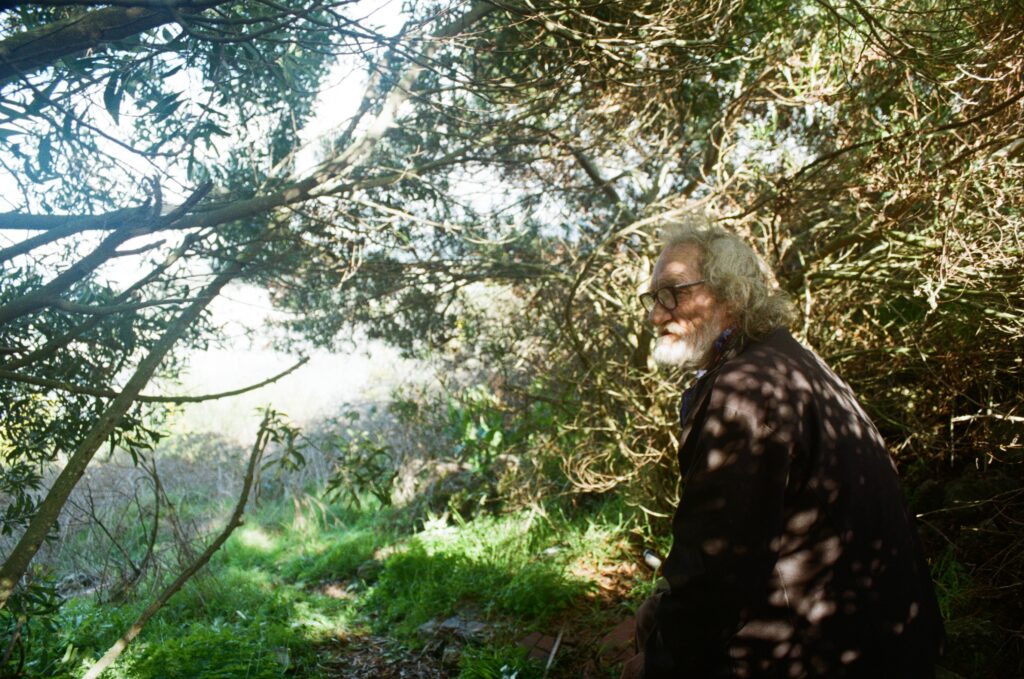

Now 71, Jimbow visits the Bulb from time to time, but it’s harder to walk the trails comfortably. On a recent visit with Street Spirit to the site of the Freeman Library, while resting on a concrete slab that once supported the south-facing wall of his home, Jimbow expressed his hopes for the Bulb’s future.

“Living here was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, but it’s still a creative place,” Jimbow said, “I’m praying these ecosystems are left alone. Let the people walk around on it, create things on it. That sense of community is always going to be here. What has happened in the past can and will arrive again.”

Bradley Penner is the Editor and Lead Reporter of Street Spirit.