The people who lived at the Albany Bulb loved the place. It has beautiful views and they woke up each morning to the songs of birds and the sound of waves. This love for the Bulb was something that the landfill residents had in common with many other people, including myself. I had been taking walks out at the Bulb for years, enjoying its nature and art. So I figured that the people living out there also appreciated the same things.

But for a long time I never talked with the folks who’d made homes at the landfill. It seemed like they just wanted to be left in peace. In 2013, though, it was becoming clear that things were going to change. The population of people living at the landfill had increased from a handful to more than a hundred, by some estimates. Advocates for making the Bulb part of the Eastshore State Park were lobbying the City of Albany to remove the people and their homes. Many large parks, from Yosemite to Central Park in New York, have resulted from the displacement of people, and this state park built on a dump is no exception.

So I reached out to the Landfillians to hear their stories, and the more I talked with them, the more I saw the things we had in common. An affection for the tiny hummingbirds and the massive acacias, an appreciation for guerrilla art, curiosity about the mysterious origins of the construction debris that made up the landfill. Of course, they knew a lot more about the Bulb and its flora and fauna than I did, since they were there morning and night and had lived there, in some cases, for years.

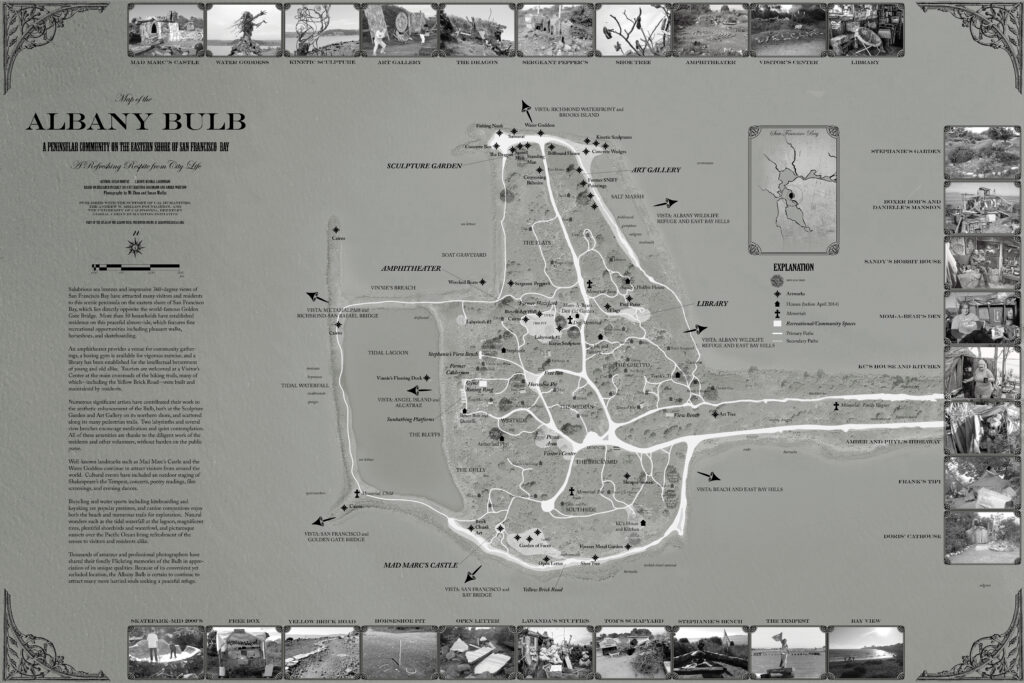

I got to know people like Amber, Jimbow, Stephanie, Mom-a-Bear, Tamara, K.C., Mad Marc, Boxer Bob, April, and so many others, and thought it was important to record and share their perspectives and deep knowledge of the place. I was teaching at UC Berkeley at the time and my students and I collected oral histories and worked with the Landfillians to map their homes and the landmarks of the Bulb. We handed out disposable cameras so they could record what was important to them. Later, we shared the maps, stories, and the photo essays that the Landfillians had made as part of an exhibition at the SOMArts Cultural Center in San Francisco called Refuge in Refuse.

Spending time with the Landfillians changed me. Now when I encounter other people who may lack shelter I know that, even though I may not get to know them, they possess knowledge and humor and talents and compassion and friends and family and have ordinary human needs and contribute to their communities. This seems almost too obvious to say, but as someone who once saw things only from my perspective as a securely housed person, I admit my former ignorance.

It’s hard to believe it’s been eleven years since the eviction. We’ve all gotten older and some of the folks I got to know have died. I run into some of the Landfillians once in a while and have learned a number of them have housing now. Some of them have joined the We Love the Bulb Facebook group and occasionally share memories there.

In the year or two after the eviction, I noticed that the Bulb had gotten so cleaned up that it seemed some of its creative spirit seemed to have been washed away. There was less art being actively made and it felt more domesticated, even sanitized. So I started an organization, Love the Bulb, that I hoped would help protect some of the wildness of the place in this new era. The Bulb has always been a changing place and it will continue to evolve. But it deserves love and care—with a gentle hand that doesn’t try to tame it too much.

Starting in 2016, Love the Bulb began organizing dance, music, and theater performances at the Bulb, and encouraged new artists to come out and create. We led nature walks,led inkmaking workshops, and hosted history talks that included the stories of the people who had lived at the landfill. The point wasn’t to curate the place but to make it clear that lots of people liked the free-wheeling, anonymous, unregulated process of artmaking out there. We organized so that unorganized, uncurated art that had nothing to do with Love the Bulb could also keep happening. And we wanted to do something to share an understanding about the community that had been there.

We started a garden in the middle of a nice flat field of rubble, and planted native species like Cleveland sage, sticky monkey flower, and manzanita. I carried jugs of water out in my bike panniers several times a week to keep the plants alive until they could survive on their own. It wasn’t a “habitat restoration”—if you restored this spot to its “natural” pre-landfill state it would be open water. In this way, the garden highlights the invasive nature of the Bulb itself, from its soils to its plants and its people, all growing wild in a shared, unregulated communion. Volunteers labeled each plant with its species name and location of origin, then wrote their names and where they (or their ancestors) were from. Almost none of us could say we were truly native.

We named it the Library Garden because it is located where Jimbow the Hobow had built and maintained a library—his home that he converted into an “art installation” in order to preserve it during a round of encampment sweeps. Jimbow and other Landfillians held poetry readings and gatherings here, and visitors and residents alike developed a system of donated and borrowed books. It was removed during the 2014 eviction.

It was important to name it the Library Garden as a memorial to the fact that the Landfillians built the kind of community institutions that people in any community build—not just the Library, but the Free Box for sharing goods, recreational spots like the Horseshoe Pit, and gathering spaces at the Amphitheater. The Landfillians liked to read and to share and to hang out together just like anybody else. By calling this spot the Library Garden, when I led history tours I could talk about the community and maybe help visitors rethink their opinions about unhoused people a bit. The Library Garden is both a living encyclopedia of plants and a reminder of the varieties of people who make up our human ecosystem.

I have passed on the work of Love the Bulb to a new team who are doing a great job tending and expanding the garden and holding events that help people be attentive to the nature and history of the Bulb. I was very happy when several Landfillians came to my “retirement” party at the Library Garden, where I passed the baton to the new leadership. We reminisced about what the Bulb was like in the old days and about the community that had created a culture rooted in the place. That was a few months before the November 2024 election. The world has changed for the worse since then, compassion seems on the wane, and the struggles of unhoused people seem harder than ever. But the fresh air, spectacular views, and wildflowers of the Bulb make it a healing place for many people.

The Landfillians were hardy, creative, and full of life in the tough conditions at the Bulb, entangled with nature in a way that housed people are often not. Trees formed the structure of many of their houses, with branches supporting tents ropes or serving as kitchen racks. When I walk around the landfill today, I still think of various locations as K.C.’s spot, or Pat and Carrie’s place, or Stephanie’s home, although they are long gone. The soil beneath my feet vibrates with memories, and the trees bear witness to the people who used to be here. I know it can be painful to return to a lost home for the people who used to live here, but I hope they come back often to enjoy this beautiful place.

Susan Moffat is the founder and former executive director of Love the Bulb.