On February 1, 1970, hundreds of tenants across Berkeley refused to pay their rent. While landlord groups claimed only about 300 units withheld payment, the Berkeley Tenants Union estimated that 824 units had joined their citywide rent strike. The “Tet Offensive Against Tenant-Slavery” lasted six chaotic months. It saw riots, gunfire, a fake kidnapping, and at least one bombing. When the strike was over, some organizers considered it a failure and a disaster. Others saw it as a qualified victory, with some tenants securing impressive collective bargaining agreements that lasted years.

The Berkeley Tenants Union had its roots in the People’s Park struggle, when community activists reclaimed land cleared for “urban renewal” and turned it into a guerrilla park in the spring of 1969. The fight for the park ended temporarily in bloody defeat, but the movement it birthed didn’t. The post-People’s Park movement synthesized large parts of Berkeley’s revolutionary left and “hippie” counterculture into a single current which centered land in its political thinking.

The closest thing that movement had to a manifesto was the “Berkeley Liberation Program,” a 13-point document written by SDS founder Tom Hayden, Judy Gumbo of the Yippies, and others. The document, strongly influenced by the Black Panther Party’s 10-Point Program, expressed the mood and ideology of the Berkeley left in late 1969 and early 1970. A far cry from Hayden’s more famous Port Huron Statement, the Berkeley Liberation Program is utopian, psychedelic, and extremely militant. Its points include: “We will make Telegraph Avenue and the South Campus a strategic territory for revolution,” “We will protect and expand our drug culture,” “We will unite with other movements throughout the world to destroy this motherfucking racistcapitalistimperialist system.” Inspired by the experience of People’s Park, control over physical space—“liberated territory”—was at the center of its strategic vision.

It was this strategic vision that led the Park movement to embark upon the brief, ill-fated “People’s Pad” experiment in June 1969 (see Street Spirit June 2024, “Don’t cut out of here when the trouble starts”). In August, Hayden and People’s Park leader Frank Bardacke expanded on the ideas of the Liberation Program in an essay called “Free Berkeley.” By creating and defending its own space, they claimed, the Park had transformed a protest movement into a liberation movement. So far, the movement had thrived on large, spectacular confrontations between activists and the local power structure. This was unsustainable, Hayden and Bardacke argued. In between crises, organization was necessary to “[build] the consciousness [and spread] the skills” required for long-term struggle, and to construct autonomous, democratic institutions to “give people experience in determining their own lives and establish a community way of life worth defending.” Among the institutions they wanted to see built were “a Liberation school as a training center,” “a free medical clinic,” “communes and crash pads,” and “a radical tenants union [to lead] a long-overdue rent strike.”

A week after the publication of “Free Berkeley,” the Berkeley Tenants Union (BTU) revealed itself to the world at a movement conference called the Gathering of the Tribes, at which revolutionary groups like the Black Panthers and the Radical Student Union rubbed shoulders with countercultural co-ops and communes. BTU, represented by People’s Park founders Wendy Schlesinger and Michael Delacour, hosted a “rent strike” workshop. Alongside more traditional tenant concerns like high rents and poor conditions, attendees at the workshop voiced interest in combating cultural discrimination by landlords who didn’t approve of “hip” lifestyles.

As summer turned to fall, the new union hosted a series of larger and larger meetings as they formalized a structure, a set of demands, and a strategy for achieving those demands. They moved into the office of the People’s Park defense campaign, rechristening it the People’s Office. They began putting together a legal team of veteran movement lawyers, like Robert Treuhaft, and young left-wing attorneys from the National Lawyers Guild. Alongside Schlesinger, Berkeley Liberation Program devotee, Jack Nicholl, emerged as a strong union leader. Mass meetings often featured a banner with the text of Point 8 of the program: “We will break the power of the landlords and provide beautiful housing for everyone.”

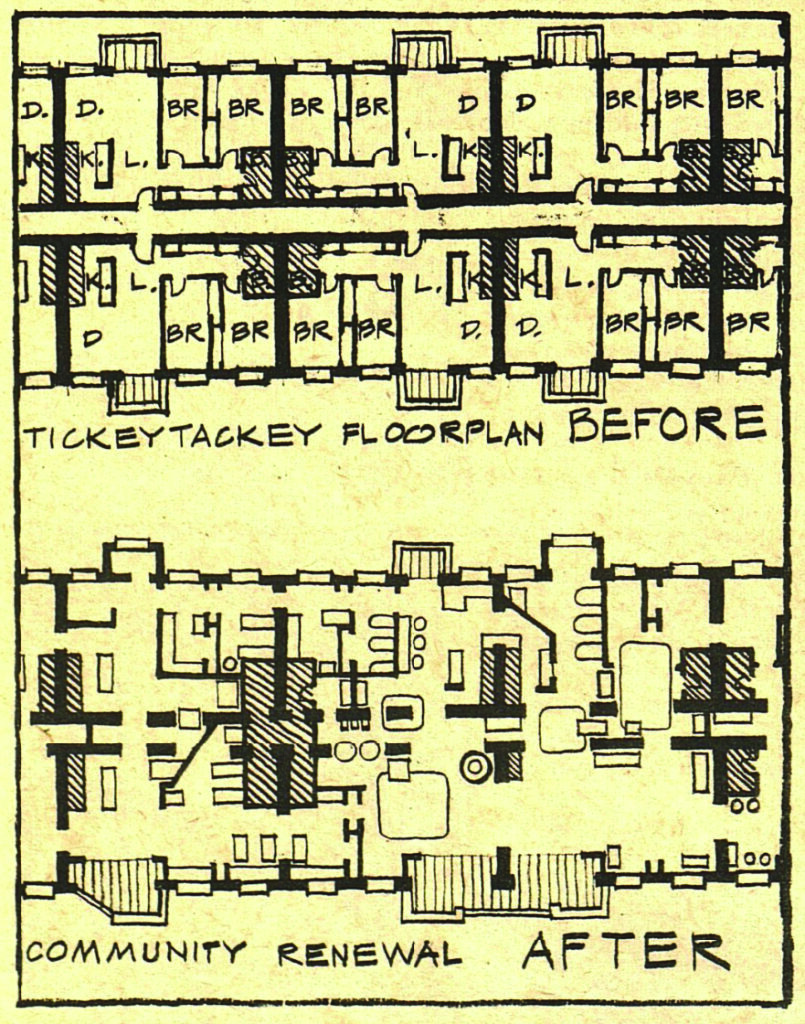

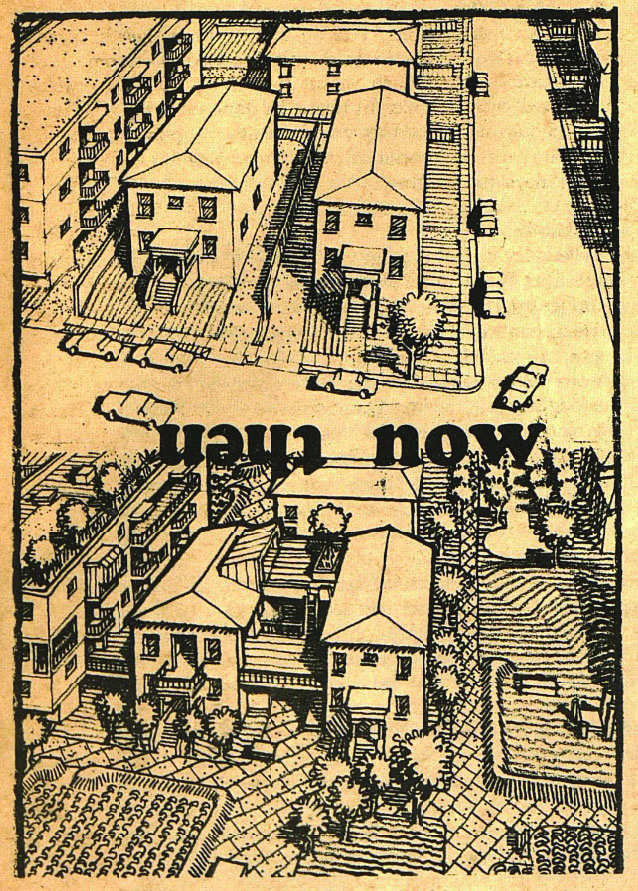

BTU’s vision of tenant organizing was more expansive than the focus on bread-and-butter issues typical of many tenant unions. From the outset, BTU was as concerned with the cultural and aesthetic issues as they were with the strictly economic ones. They sought to protect Berkeley’s “groovy old brown shingles,” considering the proliferation of cheap, ugly “ticky-tackies,” a key symptom of capitalist control over housing. In their literature, BTU advocated for the reorganization of living space to “encourage communalism and break down privatization” by removing fences and turning backyards and streets into collective gardens. They produced sketches of redesigned apartment building floor plans that would promote shared living spaces. BTU saw tenant organizing as a step toward decommodifying space and creating “new, eco-viable ways of organizing our lives.” Founded a year before the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the celebration of the first Earth Day, BTU’s prescient attention to ecological issues was fairly novel for a left-wing community organization at the time.

For most tenant unions, a rent strike is a tactic of last resort. Strategically electing to not pay rent is a high-risk action and generally requires a high level of prior organization. In 1969, however, BTU started from the rent strike and worked backwards. The tactic was settled on long before a set of demands was announced. From their perspective, the more tenants they could convince to strike, the greater the impact they would make, and the greater the blow they would strike against Berkeley’s landlords. BTU distributed tenant questionnaires and rent strike pledges all over town, collecting hundreds by the start of the new year. Still reeling from the violence of the previous spring, BTU’s grandiose plans caused panic among local authorities. “This could be the most violent situation we’ve had in Berkeley,” Board of Realtors president Jack Setzer told the papers, “It could make the People’s Park look like a picnic.” The police department announced that it was “‘considering’ the possibility of arresting the entire BTU leadership for conspiracy.”

In November, the union took its first mass action after Art Kobs, a landlord with five hundred units across eighty buildings in Berkeley, bought a house in South Berkeley and served its tenants eviction notices. BTU-affiliated tenant, Kevin Hughes, along with his wife and their infant child, refused to move. Carrying signs reading “Rent is Theft” and “Land on the Landlords,” the union led over one hundred people on a march to Kobs’ office, where they confronted him directly. During a tense exchange, a chuckling Kobs told the tenants, “There is a general practice that a person who owns property can put it to whatever use he wishes.” Shortly after the BTU delegation left his office, Kobs rescinded Hughes’s eviction notice. The union’s first direct confrontation with a landlord ended in success.

The union’s actions continued to escalate for another two months. They held a “People’s Tribunal” accusing a landlord of murder after a tenant died of asphyxiation due to an unsafe and illegal gas heater, defended a young woman from eviction after her landlord took issue with her “seeing too many boys,” disrupted the eviction of a Black single mother with a marching band, and delivered live rats captured from tenants’ houses to a city government meeting After this, the union decided they were ready to launch their citywide rent strike. At a mass meeting in January, one thousand tenants pledged to strike for the “non-negotiable” demand of union recognition.

On the first of February, the strike began. Tenants paid 15 percent of their rent to the union as dues and put the remaining 85 percent in escrow, to be released to landlords after they agreed to sign collective bargaining agreements. Some small landlords agreed to recognize the union almost immediately. Some wasted no time filing eviction notices to their striking tenants. Some attempted to negotiate with tenants outside the union framework. One landlord, Richard Bachenheimer, even told the BTU that he was “not a capitalist,” but a “leftist” who had participated in the Memorial Day march for People’s Park.

BTU developed an emergency defense system in which organizers sounded a World War II-era air raid siren while volunteers were contacted through a phone tree, allowing large crowds to quickly mobilize to buildings threatened with eviction. More than once, these crowds prevented landlords from carrying out illegal early evictions, leading police to remark: “You people mobilize faster than we do.” In the tradition of People’s Park, BTU organizers at more than one house planted communal gardens on vacant lots attached to their homes. Landlords responded with a legal offensive, suing forty-seven tenant organizers for $3.35 million.

The union saw the rent strike as part of a singular, global revolutionary movement. “Free Bobby, US Out of Southeast Asia, Stop the Evictions,” they wrote, “It’s all one.” Pointing to the University of California’s role in both war research and redevelopment/gentrification in the Bay Area, BTU argued that tenants’ struggles were materially connected to anti-imperialist guerrilla war abroad. After the fiasco of People’s Pad, in which white organizers had insensitively taken over territory in the largely Black neighborhood of South Berkeley, the BTU worked to support and build connections with Black organizers. They had a strong working relationship with Tenants on Radical Change in Housing (TORCH), a Black and Chicano tenant union operating in West and South Berkeley. They also had close ties to the Black Panther Party, who allowed BTU to publish their newspaper, Tenants Rising, on Panther printing presses. The Panthers offered BTU space in their own newspaper and connected them with tenants in crisis. The union also shared its office with the International Liberation School, a Weather Underground-adjacent group that produced informational materials on weapons training and first aid.

The “bloodshed” that Board of Realtors’ Jack Setzer had predicted failed to materialize, but some landlords threatened violence. Harry Gee pulled a gun on his tenants when they refused to remove an “on strike” banner, telling one “I’m going to fill your head with holes.” Gee later offered reduced rent to a family of recent immigrants who spoke no English in exchange for spying on BTU organizers. After talking to a Spanish-speaking BTU member, the family told Gee they would accept the reduced rent on the condition that he recognize the tenant union. The next week, the building’s BTU tenants had their windows blasted out with a shotgun. Gee was not the only landlord to point a loaded gun at tenant organizers during the 1970 rent strike. Despite their belligerent rhetoric and use of violent imagery in their propaganda, the union itself refrained from physical violence throughout the strike. In the months after the strike ended, a nighttime bombing at the property of a landlord who “played the pig during the BTU strike” did an estimated $50,000 in damage. The bombing, which injured no one, was never solved, but evidence suggests it may have been linked to West Coast members of the Weather Underground.

While some units continued striking into the late summer, most folded by the end of May. The strike’s first eviction came that month. As promised, a crowd organized by BTU swarmed police, who chased them through a dilapidated nearby building. Street fighting ensued, as police beat demonstrators who pelted them with rocks and smashed windows. By June, the union had largely collapsed from infighting. Appalled by the sexism they encountered in the movement, Wendy Schlesinger and other BTU women began meeting separately and soon emerged as an independent group, Women of the Free Future, which focused on women’s consciousness raising and self-defense training. Jack Nicholl and BTU leader, Bruce Gilbert, formed a North Korea-inspired commune with Tom Hayden in North Berkeley called Red Family, where Hayden met his future wife Jane Fonda. Gilbert became a film producer, working with Fonda on movies like 9 to 5 (1980) and The China Syndrome (1979).

The union’s legal team had successfully delayed or blocked nearly all evictions of BTU members, but few tenants were able to secure concrete victories. While hundreds of units had withheld rent, only ten landlords agreed to sign the union’s collective bargaining agreements. Of these, only one with a major Berkeley landlord. This contract, with Richard Bachenheimer’s Premium Realty, was the biggest single victory of the Great Rent Strike. It covered eighty-one units in a dozen houses and guaranteed the union the right to collectively manage their housing, and lasted in some form until 1976. Many of the houses, which operated as communes, were on a single block. Some residents removed their fences, creating a collective garden of their backyards, in order to put the ideas that animated the strike into practice. Despite its many mistakes and its sometimes hubristic ambition, the early, revolutionary period of the Berkeley Tenants Union stands as an example of housing justice organizing at its most creative and imaginative.

Matt Ray and Matthew Wranovics are the founders of Left in the Bay, a project that uncovers and retells stories of social struggle in the San Francisco Bay Area. Follow them on social media @leftinthebay.