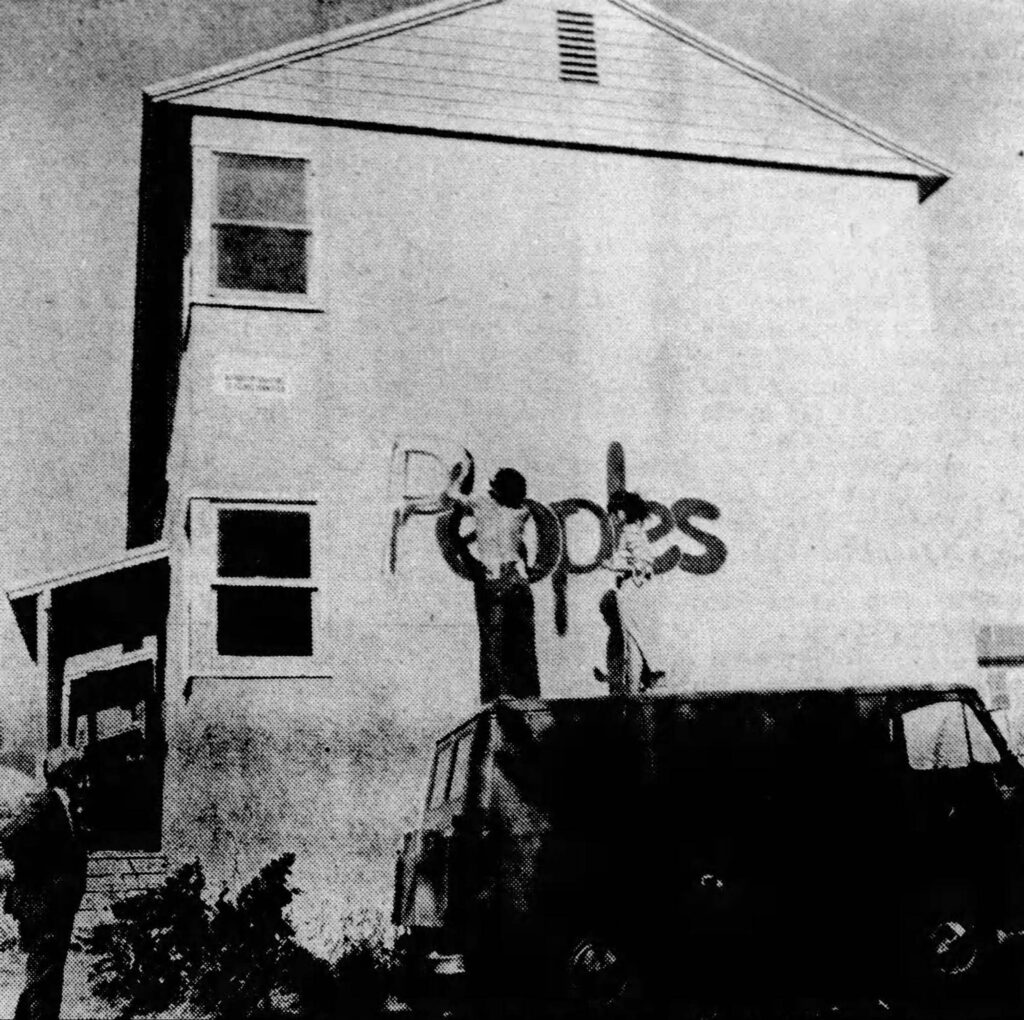

Painting at People’s Pad. (Phil Chachere, Berkeley Gazette, June 29, 1969)

“You can’t trust an ally who is doing you a favor. You can only trust comrades who are in it for themselves.” Four years after the Free Speech Movement, its most iconic figure was once again addressing a crowd on the UC Berkeley campus. Mario Savio, wearing a new beard, told his young audience that the members of their generation were “natural communists… We were born to build a cooperative commonwealth upon the wreckage of this class-ridden barbarism.”

It was June 1969, less than a month after the deadly battles over People’s Park. As a protest against a UC-led “urban renewal” program, neighborhood activists had reclaimed a vacant lot and turned it into a park. The “liberated zone” was met with overwhelming state force. After riots, a National Guard occupation, and one death at police hands, that movement ended in defeat. The park was once again a vacant lot. Savio spoke alongside People’s Park leaders, including Frank Bardacke and Tom Hayden, as they announced the movement’s next step: they were going to create a new liberated zone, not a People’s Park this time, but a “People’s Pad.”

The group marched a mile into South Berkeley where they reached the Savo Island Village housing project. Built by the military during World War II to house Navy families (among its early residents was an infant Jimi Hendrix), the barracks-like development was now mostly empty. The young radicals quickly set to work building a commune, fixing up the dilapidated buildings, painting its walls in bright colors, planting a garden, and flying Viet Cong flags. Although the youth culture-friendly bookseller Fred Cody was in talks on the movement’s behalf to lease the land legally for $1, organizers moved in before a lease could be signed, effectively making them squatters.

They had big plans. Alongside the communal kitchen and dormitories, they were going to build a school, co-hosted by the Black Panther Party. The “International Liberation School” would teach free classes on economics, law, and weapons training. No mere hippie crash pad, this was to be a genuine revolutionary base. But there was a hitch. Savo Island wasn’t abandoned. The property was owned by the Berkeley School Board, and its mostly Black residents had been evicted en masse not long before the Pad moved in. In the neighborhood, this wound was still fresh.

The Navy sold the wartime housing development to private developers in 1966 in exchange for the Estuary Housing Project in Alameda (see Street Spirit May 2024, “Bodies and Force”). The new landlords rented the badly-maintained Savo Island apartments, formerly reserved for Navy families, to poor South Berkeley residents. They quickly developed a reputation as slumlords. In the meantime, the UC’s urban renewal program was buying up and demolishing property in the South Campus area, attempting to force hippies, political radicals, and Black people out of the neighborhood. In 1967, the UC seized the block that would later become People’s Park, evicting its residents and razing their homes. It also bought McKinley Continuation High School one block away. Substituting affluent college kids for working class high schoolers, the UC built the Rochdale Village student housing complex in McKinley’s place. Obliging the UC’s desire to move the continuation high school into the Black neighborhood, the school board bought the bulk of the Savo Island site, evicting 54 families to make room for construction. In the summer of 1969, the buildings were still vacant.

Planting a garden at People’s Pad. (Fran Ortiz, San Francisco Examiner June 30, 1969).

The revolutionaries of People’s Pad were largely ignorant about this recent history. In the South Campus neighborhood, the young White militants had been able to convincingly reclaim land in the name of “the people.” In South Berkeley, many of their new Black neighbors viewed the gesture with deep suspicion, as “arrogant” at best and “imperialistic” at worst. Older and more conservative neighbors were disturbed by the compound’s nightly bonfires, singing, wine drinking, and pot smoking. Some were uncomfortable with the number of people from all over the country who passed through the Pad for short-term stays. Berkeley police considered the radical community a bitter enemy, and few in the neighborhood appreciated the increased, hostile police presence that People’s Pad attracted (harassment by law enforcement was constant at the Pad; on one particularly comic occasion, a policeman crashed his cruiser while ogling the commune’s young women).

This wasn’t a simple story of ignorant gentrifiers and aggrieved locals. Unlike other upwardly mobile Berkeley grads settling down in South Berkeley, residents of People’s Pad saw themselves as part of an international struggle against racism, imperialism, and capitalism that also included the Vietnamese National Liberation Front, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and the Black freedom movement in America. Despite some reservations, the Black Panthers had always maintained working relationships with sympathetic White leftists, whom they had long urged to take a more active role in confronting the state. It was the Panthers who suggested Berkeley radicals seize and defend “liberated” territory in the lead-up to People’s Park and, after shedding blood in fierce street combat with the police, those radicals emerged from that struggle with the Party’s respect. While the Pad’s founders had foolishly failed to cultivate relationships with ordinary residents of South Berkeley’s Black neighborhood, they did move in with the blessing and encouragement of the country’s preeminent Black Power organization, whose national headquarters was just a short walk away on Shattuck Ave.

The Party’s Charles Bursey set to work defending the Pad from charges of racism. Just a few years earlier, Bursey had balked at working with the “dirty motherfucking hippie” Michael Delacour (who went on to dedicate his life to People’s Park) when Delacour lent his psychedelic orange, blue, and green bus to the Free Huey campaign. Now the Party’s Berkeley Captain, Bursey worked assiduously to maintain cordial relationships with the countercultural left. During this period, the Panthers were the target of a massive campaign of government repression, which went so far as to assassinate leading members. In this context, the May 1969 military occupation of Berkeley led them to believe that a fascist turn in America was imminent. They decided to build a “United Front Against Fascism,” uniting as broad a range of “progressive forces” as possible, from the Berkeley youth movement to Chicano and Asian-American groups, to organized labor and the Black church. They hoped to hold its founding conference at People’s Pad. Bursey and the Pad’s communards went door-to-door in the neighborhood, polling residents on their attitudes toward the crash pad. A majority, they found, supported it. Only ten percent actively opposed it, and another thirty percent didn’t care one way or the other.

The most focused opposition came from the South Berkeley Model Cities Council, an experimental body created by one of the Johnson Administration’s War On Poverty programs. Made up of South Berkeley residents, the council was tasked with developing and managing social programs at the local level. Its makeup skewed somewhat more middle class and conservative than the neighborhood as a whole. The school board announced that it would let People’s Pad stay only if the Model Cities Council approved. At the council meeting, one long-term resident addressed the Pad favorably, saying, “You White kids are in a sense returning to the ghetto to atone for the sins of your parents…Don’t cut out of here when the trouble starts and cut your hair and wear a white shirt.” Black socialist city councilman Ron Dellums (later a 13-term congressman and the 48th mayor of Oakland) pleaded with the council: “I don’t want to see the Black community take a reactionary position…These young White people have a constructive program.” Amid charges of “fascism” by the Black Panthers, the council predictably rejected People’s Pad.

Under orders from the school board, the Pad moved out in late July, on the first day of the United Front Against Fascism conference, which was held at the Oakland Auditorium instead. The movement that came out of People’s Park remained oriented towards struggling over land, and it turned its focus to building the Berkeley Tenants Union, which organized a citywide rent strike that winter. Torn down soon after, Savo Island Village was brought back to life in 1978 as cooperatively owned social housing, which it remains to this day.

Matt Ray and Matthew Wranovics are the founders of Left in the Bay, a project that uncovers and retells stories of social struggle in the San Francisco Bay Area. Follow them on social media @leftinthebay.