Editor’s note: We have devoted the majority of this issue to “Berkeley, 94700”: a deep historical dive into South Berkeley’s Here There community encampment— which, after six years at its most recent location, was evicted by the City of Berkeley on January 31, 2023. The six full-time residents who were living there at the time moved into a motel, which is intended as transitional housing. Residents recieved official notice of the sweep two business days prior, on the morning of January 27.

The historic closure of Here There prompted us to devote this issue to its rich cultural and political history. Though the encampment we knew until the end of January was six years old, the movement that created it began over a decade before that. The closure of Here There marks a new chapter in Berkeley’s poltical history history. As we move forward, we must not forget the past.

“Berkeley, 94700” is an interactive website that includes maps, audio clips, and photographs. It is an oral history of the Here There encampment, as well as First They Came For The Homeless, the political movement that created it. It should not be read as a complete history of the camp or the protest movement, but it certainly thorough. With funding and support from the Judith Lee Stronach Baccalaureate Prize at UC Berkeley, and the Berkeley Lab for Speculative Urbanisms, Katherine Chen and Henry DeMarco spent just over 12 months researching, reporting, and writing this deep dive into Here There—and thus, documenting crucial history of the Bay Area.

Take your time with this issue. It provides a window into the history of Berkeley, and unpacks some of the cultural attitudes and social movements that have shaped the Bay Area over the last ten years. It also gives a rich description of the way encampments, like neighborhoods, can function as effective centers of mutual aid. So sit down and get comfortable. Take a breath. And dive in.

***

First they came

By Martin Niemöller

First they came for the Communists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Communist

Then they came for the Socialists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a trade unionist

Then they came for the Jews

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew

Then they came for me

And there was no one left

To speak out for me

***

First They Came for the Homeless (FTCFTH) is an unhoused protest movement that formed in 2011, in the wake of Occupy San Francisco. The group coalesced to protest the criminalization of homelessness in the Bay Area and to fight for better outcomes for the unhoused. The organization is notable for its commitment to self-led unhoused activism, as the founding members believed that those best suited to advocate for the homeless are the homeless themselves.

Throughout its decade-long history, the group collaborated with several other like-minded organizations and gained not only intense media attention, but also many community supporters. Since arriving in Berkeley, FTCFTH has staged a continuous, 8-year-long occupation to highlight the cruel treatment of the unhoused and to bring together a community in mutual support. The group has also kept its broader political commitments from Occupy, including protesting “income inequality and the privatization of the commons in the United States.”

FTCFTH formed the Here There camp, one of — if not the — longest running encampment in the Bay Area. The camp is self-governing, sober, consensus-driven, and seeks to provide proof that sanctioned encampments can thrive. Numerous former residents of the camp credit it with bringing them greater stability and helping them move towards better outcomes, including housing. The camp remains active to this day, near the intersection of Alcatraz and Adeline, in Berkeley’s historic Lorin District.

We chose to title this project ‘Berkeley, 94700,’ because it is a zip code that does not exist (Berkeley has twelve zip codes, beginning with 94701). Our animating interest in this project was how an unhoused camp exists as a neighborhood: a community of mutual aid, resource provisioning, and connection. Unlike housed neighborhoods, however, encampments cannot rely on the routine services that make a place official. Chief among these is mail delivery: to have an address is to be acknowledged, and to lack one is necessarily to be unaddressed. We imagine the Here There camp as a community with an invented zip code within Berkeley, which points towards its real existence as a place, as well as its lack of official geographic acknowledgement.

When Occupy came to San Francisco in 2011, Mike Zint was living in Golden Gate Park. He got word about the good trouble brewing in the Financial District, and moved to the epicenter of that dissent. Cities across the country were in the midst of the same tumult –– citizens were angry about the corruption, the recession, the foreclosures, and the crippling debt. Tent cities bloomed quickly and they offered shelter, food, and porta potties. In a city notable for its numerous anti-homeless laws, Occupy San Francisco was a respite for its unhoused, as well as an opportunity to make change.

James Cartmill met Mike Zint at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, one of the main strategic outposts of Occupy SF. To James, Mike Zint was a “true hero,” a captain of Occupy who honed his skills as a political strategist and activist in one of the most zealous occupations in the country. James remembers Occupy SF as a concerted battle against the Federal Reserve and the manifold abuses of the American financial system. As a photographer and documentarian, James captured the intensity and possibility of Occupy firsthand. Through Occupy, participants created an organic, living alternative to the totalizing capitalist systems that defined American life. Occupiers also formed connections and lasting bonds: James, Mike, and Stacey Hill (Bay Area native and lifelong activist) would go on to collaborate on future projects after coming together at Occupy SF. For the duration of these occupations, activists carved out spaces for protest and experimental living in the administrative centers of capitalist repression, places like Wall Street and San Francisco’s Financial District. Occupiers’ profound experiences inspired outgrowths into other movements and experiments.

It was also at Occupy where Mike Zint met Sarah Menefee, poet and longtime organizer for the unhoused. The two first conceived of an organization called First They Came For The Homeless at the Starbucks on California and Drumm St. in San Francisco, where Menefee taught youth poetry workshops. The newly born group’s motto was clear: “Homeless, not helpless. Stop the war on the poor!” FTCFTH’s first event was an occupation in front of the Macy’s at Union Square, protesting ‘Sit/ Lie,’ Section 168 of the San Francisco Police Code, the city’s Civil Sidewalks Ordinance. The ordinance makes it unlawful, with certain exceptions (like a baby in a stroller), to sit or lie on the City’s public sidewalks between 7 a.m. and 11 p.m. “Public if you’re rich,” says the flier that Mike distributed. “The commons belongs to all!

Unhoused people had been effectively ‘occupying’ cities like San Francisco long before the encampments at Wall Street; they had extensive experience dealing with police, with NIMBYs, and with punitive systems. Suddenly, San Francisco’s homeless found college students, activists, and housed people in their ranks, camping in solidarity on public space. Through Occupy, an experience of poverty in San Francisco included all those whose bedrolls were raided by the police as they slept in front of the Fed. Occupy lived on public land, and the movement asked: what is a park, a Federal Reserve, a sidewalk, if not for the people?

the only occupation in the Bay Area. Occupy Oakland was a massive movement with tens of thousands of participants, and its own distinct forms of radical, anti-capitalist politics. There was also Occupy Berkeley, which was much smaller — about 100 tents in front of Martin Luther King Jr. Civic Center Park constituted its main encampment. Occupy Cal was UC Berkeley’s campus-driven movement, more concerned about the labor inequalities affecting the education system. Even San Jose had its own Occupy. Occupy Oakland converged with First They Came for the Homeless in dramatic fashion in the years following the (approximate) end of the Occupy movement, when multiple groups came together to protest the proposed sale of the historic Berkeley Main Post Office.

On June 25, 2012, Berkeleyside reported that the United States Postal Service was planning to sell the historic Berkeley Main Post Office on Allston Way. USPS intended to shift core responsibilities to the existing Berkeley Destination Delivery Unit, and pursue a new location in downtown Berkeley for retail operations. Around the same time, USPS had listed dozens of historic post offices for sale, citing operating deficits. Despite the concerted efforts of local groups across the country, several historic post offices had already been sold. The prospects of protecting Berkeley’s Main Post Office looked grim.

Several of the groups involved in efforts to protect the Post Office, and resist privatization more broadly, came together to form a coalition called the Berkeley Post Office Defenders (BPOD: pronounced bee-pod). For those involved in the resistance, what was at stake extended far beyond one post office: this was about combating austerity, about refusing to sit idly while public resources were shorn away in the name of ‘cutting operational costs.’ BPOD’s timeline was explicit from the start: the protest would end when the sale was reversed, and no earlier.

While the city and USPS battled in court, BPOD and FTCFTH continued their occupation. The encampment persisted in front of the Berkeley Main Post Office for 17 months. Throughout their lengthy tenure at the post office, occupiers weathered rainstorms, endured sustained harassment by Postal Police officers, and planted a community garden, which they christened the Garden of Common Good.

Hudson McDonald, a Berkeley developer that had been working to purchase the post office, was ultimately unable to reach an agreement with USPS, and the sale did not proceed.

The camp was evicted in April of 2016, nearly a year and a half after its inception. The saga concluded in May of 2018, with a decision from U.S. District District Court Judge William Alsup, which upheld the constitutionality of an overlay ordinance passed by the City of Berkeley in 2014. The ordinance protected several historic buildings, including the Main Post Office. Though USPS could technically still legally sell the building, the site remains a post office today, and Judge Alsup’s decision was never appealed.

First They Came for the Homeless members and supporters remember the Post Office Occupation as an important victory and a vital part of the organization’s history. As with earlier and later occupations, the post office defense involved many flashpoint clashes with police and agitators. For all the support that the occupation received, they also faced their fair share of criticism and ambivalence, and occasional outbursts of aggression. Maintaining camp order and solidarity were necessary and ongoing struggles, especially in the pursuit of a positive public image. Despite these hurdles, the occupiers’ goals were realized in the halting of the post office sale. The Post Office Occupation was a powerful, highly visible statement that laid necessary groundwork for the eventual establishment of the Here There camp.

It was Tuesday night, November 17, 2015. People had been holding vigil outside Old City Hall since 6am on Monday, fasting and “sleeping out” in solidarity with the homeless. This camp was a new venture of FTCFTH, occurring concurrently with the ongoing Post Office Occupation. They called themselves Liberty City. 30 people marched from Liberty City to Longfellow Middle School, where they joined a queue of people waiting their turn at a microphone.

That night, Vice Mayor Linda Maio was bringing forth a proposal to “Improve Conditions on our Community Sidewalks.” If instituted, the ordinances would prohibit people from having more than two square feet of personal possessions on sidewalks from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. Not two-by-two square feet, but two square feet. The proposal would also outlaw laying down inside planter beds or on planter walls. Those with shopping carts would be forced to move belongings to a new block every hour, and those who failed to comply with these restrictions could face a steep fine.

One notable inclusion in the proposal was an ordinance prohibiting public urination and defecation, crimes that were already well established in county and statewide code. These additions were entirely redundant — the statewide code against public urination was enacted in 1872. Homeless advocates speculated that their inclusion was meant to bolster popular support for the proposal and discredit detractors.

The new ordinances would be enforced upon the installation of an alternative storage option: 50 lockers, for Berkeley’s unhoused population of nearly 1,000. The total estimated cost of implementing the ordinances came up to $300,000 per year. After four hours of fervent testimony from the public, the council held a preliminary vote at 12:30 am. They voted to pass, 6-3.

As with previous FTCFTH camps, Liberty City abided by the values of consensus and sobriety established during Occupy: the camp enforced rules including no drugs, no alcohol, and no violence. During the occupation, camp members worked to maintain an orderly community and ousted members who violated their behavioral standards. Their protest persisted after the city council’s preliminary vote as a way to resist the new ordinances, which protesters felt would further criminalize homelessness in the city. However, they received a cease and desist order from the city at the end of November, ordering all those camped near Old City Hall to disband.

At the City Council meeting on December 1, 2015, members of the public once again lined up at the mic, many using their allotted one minute to oppose an ordinance they considered cruel and punitive to Berkeley unhoused communities. The auditorium of Longfellow Middle School was crowded, and as the night wore on, the energy became volatile. Vice Mayor Linda Maio grew increasingly impatient with the dissenting citizens. A vote to extend the meeting to 11:30 p.m. did not pass, and Councilman Kriss Worthington had the floor. Maio interrupted, accusing him of running down the clock to avoid a vote. This brought the crowd to a fever pitch.

A member of the crowd took to the mic. “It is a violation of the California Brown Act, to deny people the right to speak,” JP Massar said, citing the legislation that ensures citizens their right to participate in local governments. Maio continued to speak over him, calling for a vote. Massar then repeated his mantra. “You have the right to clear the room, but you do not have the right to deny people the right to speak,” he said, his voice bellowing over the soundsystem. The council passed the ordinance. Berkeley police evicted the residents of Liberty City three days later.

Maio’s ordinance was adopted, but the policy was not enforced because the proposed lockers had not been made available. Providing lockers was the responsibility of the City Manager — to some, this failure suggests that perhaps the City Council passed this ordinance only under pressure and in the heat of the moment. Another possibility is that the ordinance was simply too broad to allow for effective enforcement: constantly policing the exact geometric bounds of every unhoused person’s possessions in Berkeley is a massive, costly, and, ultimately, impossible project.

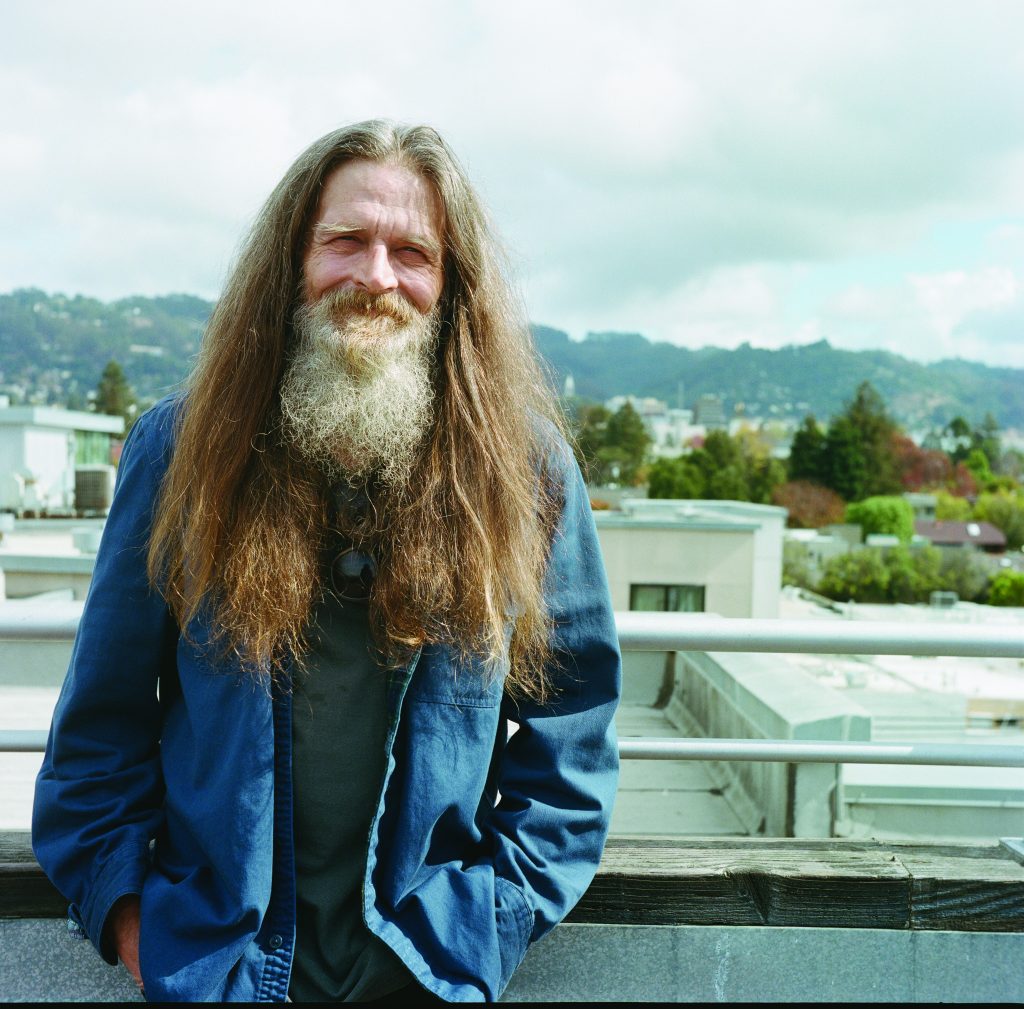

In October of 2016, Mike and company were in front of the Starbucks on Shattuck. The City of Berkeley had just redesigned its homeless services to a bottleneck: the Berkeley Food & Housing Project, known as “the Hub.” The Hub was the new one-stop shop for all homeless services. For individual agencies, this meant that offering services without referral from the Hub would threaten their funding. For people needing services, it meant bureaucracy, and the end of receiving aid on the same day it was needed. Dan McMullan, long-time activist for the disabled and unhoused, founder of the Disabled People Outside Project, and (at the time) human welfare commissioner for the City of Berkeley, grew frustrated with these changes. Dan had met a disabled woman who had lost her housing and her ID, and took her to the new Hub –– it was his first time there, and he was shocked at how unhelpful they were. The Hub rejected her, and she slept outside for several nights.

Under the prior system, Dan explained, you could try multiple locations around the city. If refused at one, you could try somewhere else. Places could often get people in on their day of need, and you could call around and find someone who might fit you in. It was more of a human configuration: advocates developed friendly relationships with intake workers, who were familiar faces willing to help out when someone needed a bed for a night. But the coordinated entry system changed all of this.

What Dan saw at the Hub left him angry. He ran into Mike Zint in front of the Starbucks on Shattuck Avenue when Dan was returning to the Hub that day, and the two hatched a plan to stage ‘The Poor Tour,’ a long-term touring parade to protest the state of homeless services and the criminalization of homelessness in Berkeley. A broader coalition formed, and the planning process moved forward. Dan, Mike, Sarah Menafee, James Cartmill, and Michelle Lot met at Starbucks to discuss strategy and locations, and soon, The Poor Tour began in earnest.

Their first stop was the Hub. The group made their camp as visible as possible, displaying signs with slogans like “Snubbed by the Hub!” There, others joined the group, growing its strength and numbers. “Not too long after I joined the encampment, we were raided by the police,” says Benjamin Royer, a disabled member of FTCFTH. “And then we kind of went on what was called The Poor Tour. Police raid after police raid after police raid.” The eviction at the Hub was the first of many as the group toured around the city, and ultimately camped in 14 different locations.

Over and over, the police evicted camps, often descending on FTCFTH in the early hours of the morning. Multiple members and supporters shared their experiences of these “raids,” recalling the disorientation and panic they felt as a result of these eviction tactics. Again and again, camps were flipped through, possessions were seized, and activists were forced to start from scratch in a new location. Community supporters were awakened in the early morning by alerts from campers, and would rush to the site of the eviction to monitor police and assist with packing and preserving possessions. At every stop, Dan McMullan and other supporters were there to provide new tents and stoves to replace the items seized in the evictions. Dan recalls being awakened to respond to night-time evictions at least 13 times during this period.

Many on The Poor Tour remember this time as a crucible in which the values of FTCFTH were forged and strengthened through extreme adversity. As with previous FTCFTH and Occupy settlements, the camps served not only to cast a blinding spotlight on the conditions of being unhoused in Berkeley, but also to offer an intentional community of solidarity and self-determination to those experiencing homelessness. The camps were highly visible, made more visible by colorful signs. They were hard to ignore, by design.

In the end, FTCFTH camps on The Poor Tour were evicted at least 14 times. With every eviction, members of FTCFTH lost vital, life-sustaining medicine and possessions. But, as many have pointed out, The Poor Tour was also a victory, in multiple ways. For one, their size and support effectively exhausted enforcement. During the tour, many unhoused people gained shelter, community, and the opportunity to make a statement.

The last stop on The Poor Tour was the Here There Sculpture near the border of Oakland and Berkeley. Here, FTCFTH found a community willing to welcome them and offer them support in their pursuit of independent stability. FTCFTH settled in the Lorin District, a historically non-white community in South Berkeley, setting up a camp near the sculpture on Adeline Street. That camp would come to be known by the same name as the sculpture: Here There. There were many, many other important participants in The Poor Tour who were unfortunately not able to be contacted and included here, given the constraints of this project. Their voices live on in the manifold articles and blog posts written about The Poor Tour.

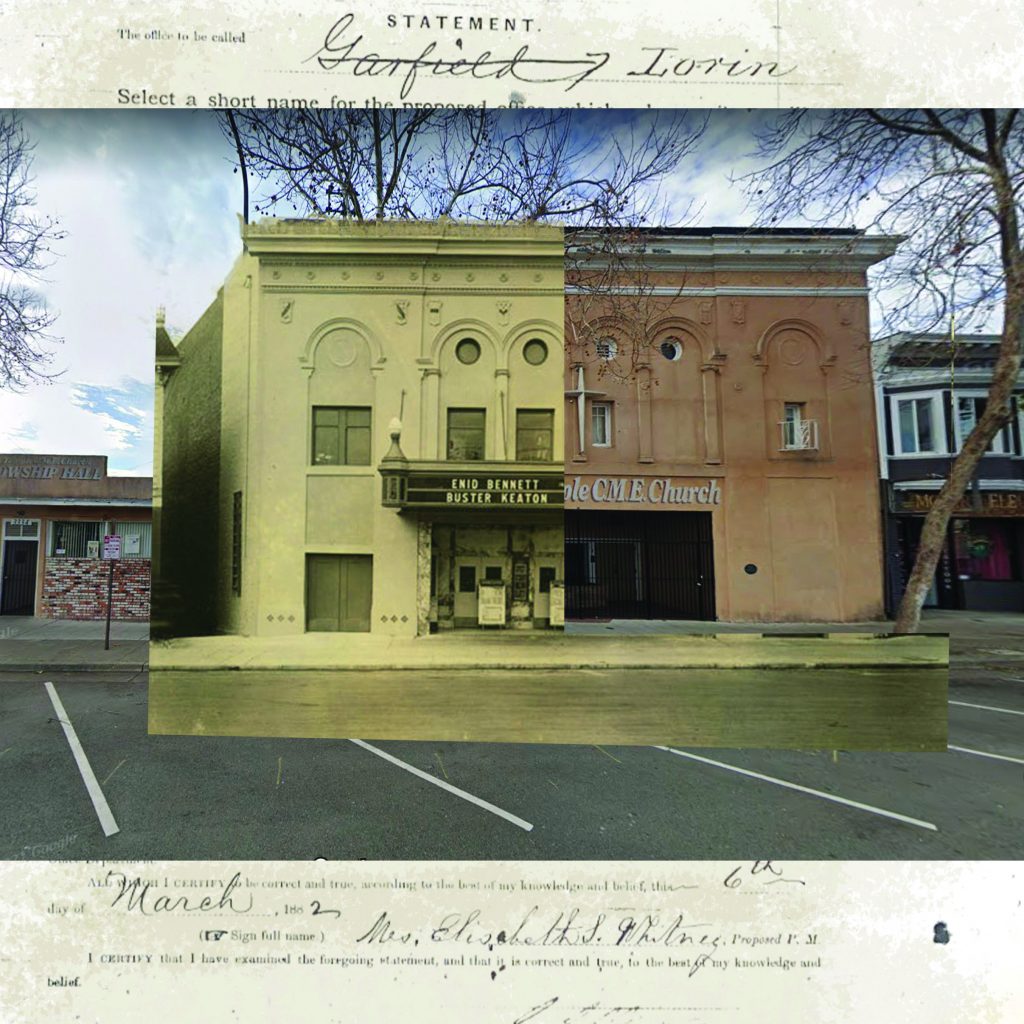

In 1876—long after the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone people who lived on the Huichin territory we now know as Berkeley had been forced off the land—Governor Leland Stanford and real estate developer Francis Kittredge Shattuck had plans to build a train line. They bought a right-of-way to allow a steam train spur line from Central Pacific Railway in Oakland to Adeline Street and Stanford Avenue, ending at Shattuck and University. The spur line effectively stitched Oakland to Berkeley, by way of Lorin Station on Adeline and Alcatraz.

Lorin emerged in the 1880s as an admired village of Victorian houses on Oakland’s border; when it was annexed in 1892, this area of South Berkeley came to be known as the Lorin District.

From 1910 to 1970, approximately six million Black people moved out of the American South to the North, Midwest, and West, to pursue educational and economic opportunities and to escape from the mounting violence of Jim Crow. Known as The Great Migration, this was one of the largest movements of any group in American history.

Although migrants moved to escape from racial violence, they were met with similar racism in their new communities from white people who were furious with the changing demographics. Black people who migrated after World War II were met with organized pushback from the white localities, who were implementing discriminatory and segregationist practices.

In 1984, Grove Street, a central artery of Berkeley, was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Way. Grove Street had been understood in this city as an unofficial line of segregation, but New Deal-era loaning practices had made such a line official. Under President F. D. Roosevelt, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created to provide affordable mortgages in the wake of the Depression. HOLC needed to assure banks, however, that borrowers would not default. The organization drew up lending security maps of major American cities, supposedly for banks to assess lending risks. In reality, the maps produced were informed by the demographics of different neighborhoods, with the various ‘grades’ being encoded with an area’s racial makeup. The maps separated cities into four grades: A as “best,” B as “desirable,” C as “declining,” and D as “hazardous.” The best areas were green, the most hazardous areas were red.

In Berkeley, MLK Jr. Way was the line that divided the red from the rest. Redlining inscribed racist notions in space, classifying non-white neighborhoods as ‘hazardous’ and effectively legalizing discriminatory lending practices. Redlining was only one of many legal and financial implements that contributed to segregation in U.S. cities and produced geographies of difference in which non-white residents were exploited, denied services, and shut out of opportunities for wealth creation. This is the necessary context for understanding Lorin, a vibrant, historically non-white community that lay south of the literal red line that was once Grove Street.Thousands of Black people moved to Berkeley in the 1940s. Many newly settled Black Berkeleyans worked in shipyards in Richmond as part of the burgeoning wartime defense industry. White property owners in Berkeley worked tirelessly to exclude the city’s non-white residents from housing opportunities, petitioning the city council to implement racial zoning laws. The Berkeley Realty Board was a favorite instrument of financial discrimination: the board supported the creation of neighborhood covenants that excluded would-be non-white home buyers, particularly Black and Asian people. Also worth noting is that Berkeley was the birthplace of single-family zoning, a practice that began in the city’s Elmwood neighborhood in 1916 with the explicit intention of preventing a Black-owned dance hall from entering the neighborhood.

Given this history of racist geographies, the Lorin District was one of the few areas in Berkeley where Black and Asian residents could live. Prior to the start of the Second World War, the neighborhood had a large population of Black and Japanese residents, but the US policy of Japanese internment further shifted the area’s demographics, as many former Japanese residents lost their homes and businesses.

This is, of course, only a bare account of the Lorin District’s long and storied history. Those best able to speak about the neighborhood’s history are those who call it home. Miss Richie Smith, a retired Head Start teacher, Lorin resident since 1949, and beloved community leader (sometimes called ‘the Mayor of South Berkeley’) remembers her experiences when she first came to Lorin.

“I arrived here in 1949. I attended school here, received my education here. And I married, produced a family. I am a retired Head Start teacher, and I have been doing community work early on, because when I arrived here in ‘49, this was the only place that people of my hue and color could find a place to live . . . But this place was populated with people of color, right where we’re sitting in this block, was populated with doctors, lawyers, realtors, and a whole array of business people of color.”

“This busiest intersection up here at Adeline, which was Grove, was an invisible red and black line, so that people of color could only live in this area,” says Miss Richie, gesturing towards the divergence of MLK Jr. Way and Shattuck. “And the way that some made it across this invisible line was that they were a nanny, a housekeeper, a gardener of some Caucasian person. And when they shared their concerns of trying to purchase a home that they had found across this invisible red and black line, they shared that they could not get together with a creditor or bank that would loan them the money. So the employer stepped in, made the deal, and they made the payment to that person and when it was paid off, they placed it in their name. That is how some people of color made it across the line into the better communities and neighborhoods.”

The Lorin District was filled with prosperous black-owned businesses that attracted residents from all over the Bay.

“Well, we had three or four supermarkets in this area,” Miss Richie remembers. “We had a variety store. The building on the corner there, the hair braiding shop, was an Afro-American Rexall drug store. Across the street light, now that’s a bar, that was Wells Fargo Bank. Up on the next corner was Bank of America. We had all of these entities here in the neighborhood. People would come here and stay all day, shopping and partaking of what we had here.”

In addition to the ongoing histories of redlining, disinvestment, and other racist policies, the Lorin District has long been a center of community resiliency, solidarity, and activism. Some Black residents of Lorin held property for their Japanese neighbors during internment, safeguarding these homes until their neighbors were able to return. More recently, a group of South Berkeley neighbors came together to form Friends of Adeline, an organization that, in their own words, works “to affect change so that our neighborhood is an inclusive and just place for all people.”

Some of Friends of Adeline’s goals include working to exert local self-determination over the future of the neighborhood, advocating for the construction of affordable housing in the neighborhood, demanding infrastructural improvements and investments geared towards all members of the community, resisting gentrification, and fighting for the ‘right to return’ for people of color pushed out of the neighborhood by uneven development and racist policies.

Friends of Adeline pinpoints its beginnings as an announcement from the City of Berkeley in 2015.

“The city put out a call, an announcement that they were going to do this project to address housing,” recalls Tony Wilkinson.

It was an alarming evaluation of the place he and his wife Margy called home.

“It was a pretty well attended conversation. But when the city’s economic development people were describing the project, the way they talked about the existing community… It was more about, ‘All the exciting things we are gonna do!’ and not, ‘What are we drawing from?’ not, ‘What is the history of this community?’ or, ‘What are its needs?’ … [It seemed like] an opportunity for new people to come in and [build] new buildings. So that was disturbing.”

During the meeting, Tony remembers one woman who got up and said something to the effect of, “Gentrification’s been happening and a lot of families have been pushed out. How’s this project going to address the needs of Black families to remain in South Berkeley, to have a place in South Berkeley or to come back?” Mayor Tom Bates said something about how his hands were tied, how he couldn’t control rents or prices of housing or land. Then, by several accounts of those present at that fateful meeting, he said, “We would love for you to stay. But if you can’t, maybe you’d be happier somewhere else.”

That was the beginning and end of the response to the question of pushout ––the callousness sent shockwaves. But then-Councilmember Max Anderson suggested that the frustrated community members take action independently to develop a vision of their needs, which they could present to the city. Max even suggested they come up with a name for their group, something like, ‘Friends of Adeline.’

The group began to envision a mission statement for their community. Then, the city came forward with a new budget. Friends of Adeline got a hold of it and did an analysis –– they found that two-thirds of the cuts to the old budget were directly solely at the nonprofits that serve their South Berkeley community.

After several heated public meetings and discussions, it seemed that Friends of Adeline mounted a successful defense. The project was halted in the middle of the process, and the city fired a company that had been working on outreach.

“I think what they were worried about was, they were not getting the results that they were buying,” said Tony Wilkinson. “They were spending a lot of money, a $175,000 grant to have this study, and it was coming out all wrong, so they just stopped it and dismissed this thing, and then tried to figure out how to restart it.”

As The Poor Tour came to an end in January of 2017, FTCFTH entered a community willing to extend support and compassion. Miss Richie proposed that the camp seek solace in Lorin.

“Complaints of the powers that be that are in North Berkeley, the hills, and what have you: they don’t want this kind of living in their community,” she remembers. “So I met up when they were moving them out, and they used to do this at night, so I suggested that they move to Here and There. And that is what they did, they quietly set up camp there.”

Tony Wilkinson recalls that people in the community such as Miss Richie, Christina Murphy, Willie Phillips, Edy Boone, Elaine Bloom did not see the encampment residents as ‘others.’

“They saw them as, in a way, it’s like, this is a neighborhood, these are neighbors, these are people struggling with some issues and they need help… as long as they saw themselves as part of the bigger community…and worked with the community, then they were part of the community,” said Tony.

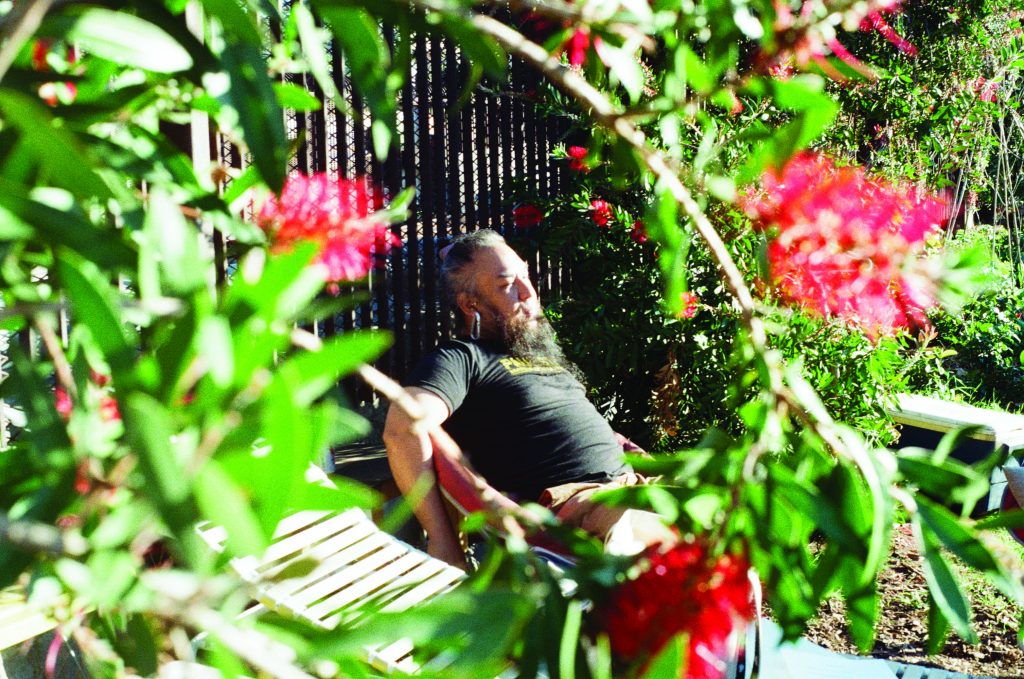

The location near the intersection of Alcatraz and Adeline proved fertile ground for the establishment of the Here There camp. This area had trees and a lawn, making it clearly safer and more habitable than the sidewalks and street corners where FTCFTH had camped during The Poor Tour. The camp took its name from the art installation at the site where they settled, a massive sculpture of steel that read “HERE” and “THERE,” denoting the boundary between Berkeley and Oakland. According to the official City of Berkeley press release, “the sculptured letters form a poetic message of hello and goodbye and provide a sense of place,” and contribute to “the literary and narrative history of Berkeley.”

FTCFTH was on BART property now, and the raids had stopped. They could stay for more than a few nights, and the camp began to envision permanence. People like Mike Zint and Dan McMullan had long pushed for the city to create a sanctioned encampment site, and here was an opportunity to show proof of that possibility. The camp focused on making an exemplary space for stability and self-advocacy.

“One thing Mike Zint always talked about — was that stability is the first, number one thing for when you find yourself without a home, without a space, without a shelter. You have to establish stability, so that you can catch your breath, be calm, and make good decisions about what is going to happen,” says Tony.

Though the camp would eventually secure the support of local groups and businesses, not everyone in the neighborhood was initially enthusiastic about the arrival of FTCFTH. Some business owners and employees worried the new arrivals would have a negative impact on commerce. Amanda Ruth-Chouinard, current owner and former employee of beloved local cafe and bakeshop Sweet Adeline, remembers concern in the shop when FTCFTH moved in.

“I remember the first day that they moved in. I don’t remember talking to anyone specifically from the camp at that point, I just remember being like, Whoa, this is happening! And being kind of alarmed, a lot of co-workers and us were like, this isn’t going to be good for business, there’s tents across the street,” says Amanda. “But you kind of realize this is saying something: they have to live in those tents across the street. This is saying something about our economy and the times . . . And it’s not like they would come in and use our bathroom and not buy anything: they would buy a lot of stuff every day!”

Over the following months, the support of groups like Sweet Adeline, Consider the Homeless!, Friends of Adeline, Youth Spirit Artworks, and Lifelong Medical, in addition to networks of neighbors, would prove vital to the camp’s longevity. Though any camp must necessarily fight for its survival and resist the ever-present threat of eviction, the relative stability found at the Here There site allowed FTCFTH to undertake more ambitious governance and infrastructural projects.

The camp’s goal was to provide proof that the people best suited to advocate and organize the unhoused were the unhoused themselves. It was an effort of liberation.

“What we achieved through the ‘occupy’ [at Here There] was changing the reality of what being homeless is,” says Stacey Hill. “And prior to that, it wasn’t happening like that out there. By the time people got out there, that was it. The only way they got out of that was if people from the outside came and got them out.”

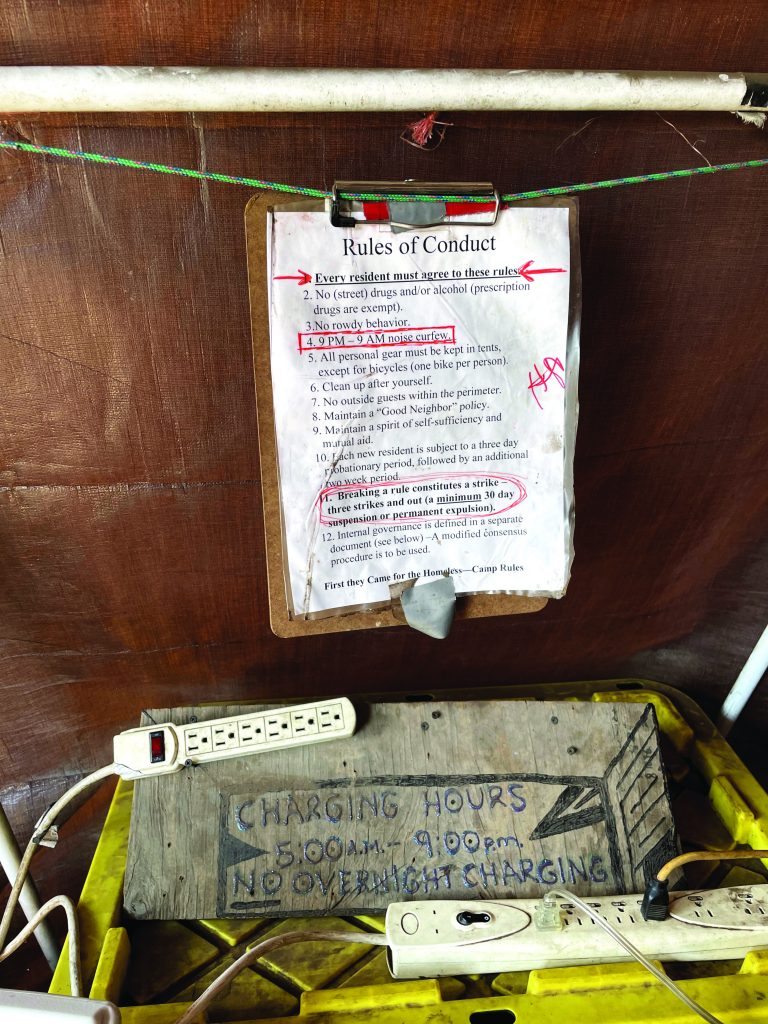

Settling at the Here There site allowed the camp the stability needed to develop more sophisticated infrastructure and policies. As with all prior FTCFTH camps, Here There practiced consensus-based self governance and enforced several simple, yet firm rules including: sobriety (excluding marijuana, for medicinal purposes), cleanliness, noise curfews, attendance of weekly meetings, no violence or fighting and more. The camp’s rules were designed to be flexible enough so as to not be coercive, yet strictly enforced enough to maintain a safe and organized atmosphere.

“You just had to read them and agree to them, basically. Oh yeah, the breaking of a rule would gather you a strike, and if you got three strikes, you’d be out,” says Julio, a recent resident of Here There. “And sometimes we’d have to kick people out. And sometimes they’d leave quickly, other times we would just have to go through some shit just to get them out.”

Stability and Sobriety

“It’s not just sober. I want to extend the ‘stable’ part of it, and the function,” says Toan Nguyen, a former member and active advocate for the unhoused. Many people who come to the camp have already seen the city’s official services –– the first-come-first-serve shelters and resources that enforce curfews and leave the latecomers in the cold. “It’s more of a controlling atmosphere, with the city-run programs,” he explains. “But the camp provides a stable place for people to get back on their feet, just to make it more clear.”

“People are unhoused for different reasons,” says Toan. “We don’t ask them why they’re unhoused, they can share if they want to. But it can be personal, I mean people don’t want to share. Oh, because I have a disability, or I have mental health… or I got evicted. Some things can be triggering or emotional or personal, so they don’t want to share that… but since it’s a community, like a tight-knit community, eventually people share in conversation. People share and we get to know each other, and we get to know how they are and how we can help one another.”

Then there’s the sobriety element — a strict rule that has become synonymous with the Here There camp. “The reason why the camp is strict on alcohol and hard substances is because, as you know, it affects people’s behavior. Whether they’re trying to do right, or whether their intentions are good or not, alcohol will really influence their behavior. To be in a sober environment, I think it helps everyone,” says Toan.

In some cases, the stability afforded by the camp was literally life saving. “Well, the memories that I have of Here and There are that it was a stable place to stay while I waited for housing,” says Ben Royer. “If it hadn’t been for the Here There camp, I probably would never have survived.”

By creating and enforcing these rules, the camp gave its members the chance to improve their wellbeing and work towards security. Sam, former camp resident, described stabilization as the primary ‘job’ of camp residents.

“You’re waking up, you’re smoking pot, probably, you’re drinking coffee, then you eat something and then you go walk around town a bit. Your job at the Here There camp is to try to stabilize: that’s your job. Stabilization for a lot of people happens by smokin’ pot and drinkin’ coffee and keeping to themselves. That’s how it’s accomplished. That’s what you hope for. There’s not a lot of responsibility going on there…That’s not what it’s there for — it’s a stabilizing environment, not an ambitious environment.”

Weekly Meetings and the Block Funcion

The camp also practiced collective decision making, holding weekly meetings on Sundays where everyone abided by the principles of consensus. These meetings addressed a wide variety of camp business, such as deciding on desired improvements and managing the use of collective funds. Meetings were mandatory.

Meetings could become heated, and some found the requirements of consensus frustrating. One particularly polarizing feature of meetings was the ‘block’ function. Members could block any action that they objected to, which would prevent that from proceeding until the block was removed. Essentially, any member of the camp could veto a decision. Leslie, another previous resident, recounted the purpose and value of blocks, though he never used one himself.

“There was structure there and I really liked the way the government worked, where everybody got a chance to have a say at a meeting and you could . . . block proposals with your single vote if you had some inside information that the whole camp knew nothing about regarding a subject. You could fill everybody in while you blocked it. So you would block proposals that would endanger the camp. Somebody you know would not be able to follow the rules, you could propose a block as the camp might be unfamiliar with them but you might be familiar with them from the streets. It really did give everybody a chance, that kind of government that we had.”

Others questioned whether blocks actually contributed anything valuable to the process. Alex, a former camp member, believes that blocks ultimately did more harm than good. “I don’t necessarily think that a consensus governance is per-say ineffective. However, that block function… it has to be done very, very carefully, and you have to make sure that people who are doing it are able to go into it from the mental and emotional maturity of where ‘we have to reach a consensus.’”

Joining Camp

Sunday meetings involved a fluid, variable form of governance. For some, meetings were an opportunity for learning and growth.

“I enjoy the process of figuring out how we can, within ourselves (or how I can within myself), let go of notions of hierarchy and control, and autocracy, or this idea that there is someone who knows the answer and that person is the leader and they need to be somehow glorified,” says Tim.

Meetings had another notable function: screening new members. The camp essentially conducted its own outreach, as members found and invited other unhoused people to join the camp. These would-be new members would attend Sunday meetings and introduce themselves before they were approved to formally enter camp. The process of entering camp was not immediate, even after attending a weekly meeting. The camp had a probationary period before those attempting to join were given full membership, which was intended to screen out any inappropriate behavior by a consensus vote.

Toan provided more details on the entry process for new members.

“…Unless it’s urgent or an emergency… and someone from the camp can vouch for them, [people are] required to go through a process of coming in, which is attend the meeting, introduce themself and answer questions…and if everyone is willing to give them a chance, or if there’s no objections, they’re able to come in, live inside, and then people will make sure they have a tent, beddings, and a space, everything they need. And they get put on probation period….During the probation period we ask them to attend a meeting, just to follow up to see how they’re doing, any help they need, or if there’s any issues with them. And after the probation period, they get membership status.”

The Probationary Period

“So the environment will kill you,” says Sam, referring to the harsh noises and attitudes of Berkeley’s downtown corridors. “By the time you’ve come to Here There, you’ve been killed by the environment. Somebody finds you, brings you, sees if you can hold it together for a few days, and then you get to stay.”

As with the ‘block’ function, opinions on the value of the probationary period differed from member to member. Some felt that the probationary period was valuable for protecting the camp from possible threats. Others believed it was too harsh, and further traumatized people who had already experienced tremendous adversity.

Leslie, however, actually worked to lengthen the probationary period during his time at camp. He felt that an extended probationary period would be more effective for flagging potentially disruptive people before they had a chance to cause structural problems.

“I did make changes in governance by proposing amendments or changing roles like increasing a probationary period from two weeks to a month,” recalls Leslie. “We had a few folks that did not start acting out until about a month, and I just thought it would be a good idea to have it be a month long… it seemed like people took about a month to act out if they were gonna act out. I did not even think about what the other fella [Sam] said when we were at the park about how that stresses people out to be on probation. Never gave it much of a thought when I proposed that rule, but I guess it would.”

Governance Roles

Camp members also occupied governance roles. “I ended up being proposed to be the treasurer by Joe at a meeting, which took me by surprise, I was not expecting it,” says Leslie. “I would hold relatively small amounts of cash for the camp, petty cash. And I kept a detailed log of the money: what it was spent on and who got what and how much change came back.”

Beyond administrative functions like meetings, managing new entries, and handling funds, camp members worked to make the space functional and pleasant. The camp’s physical infrastructure greatly contributed to the waves of media attention it attracted over the years. Eventually, the camp featured functional solar panels and batteries, a kitchen tent, and a garden.

The camp’s organized appearance also helped draw in new members. Alex remembers being impressed with the camp’s structure, which contributed to him joining.

“It was probably the cleanest and best camp you could go to, that I had seen,” he says. “The fact that it was fairly well organized, and there were solar panels and things was really great. The political nature of it really made me excited about what we could do, and I was really excited about doing all the city council meetings.”

Despite the camp’s political reputation, not everyone was personally interested in making a change within the larger picture.

“I think for a lot of people there, it wasn’t totally political. I think a lot of people just kind of wanted housing for themselves,” says Alex. “And I think that’s fine, I don’t think it necessarily had to be political. The existence of people without houses is political itself.”

“The people there were good people. Some of them were derelicts, some of them weren’t,” says, Kent, another former resident. “But, you know, the definition of a ‘derelict’ is someone who doesn’t care about themselves. Most of these people just care about getting a home.”

Waste Management

Even with the camp’s organizational achievements, basic struggles remained. One of the most enduring challenges was waste disposal. The provision or denial of trash collection is one of the most significant powers that cities have over encampments. The accumulation of trash at a camp contributes to complaints from the surrounding community, so a camp’s ability to dispose of its own trash is paramount for its longevity. Residents of Here There took on the responsibility of trash disposal, which was a lengthy and difficult process during the earlier periods of the camp.

Eventually, the City began to provide assistance with trash pickup. “They also developed ways to work with the city in terms of collecting trash,” says Tony. “They got a guy from the city who would say ‘Here are the bags, if you put your trash in these orange bags, I will pick them up. Have them at this place, at this time, boom.’ Trash did not accumulate, which means there are no rats.” In addition to trash disposal, controlling rats was a vital element of daily camp maintenance. The camp went to incredible lengths to ensure that the ever-present rats were kept at bay.

Pest control

“Rats are nearly blind,” explains Stacey. “They function on their sense of smell.” Cleaning up scent trails at the camp is essential to derailing a rat population. It’s a bit of an arms race –– one needs to outsmart, outwitt, outplay the enemy. But the enemy is formidable, as Stacey knows.

“Urbanized animals are different from wild animals, and rats are really smart. There is no way I can emphasize just how smart rats are. If you are thinking you outsmarted a rat, I guarantee you, that rat has got your ass. He has already won.”

Recent camp resident Atlas has taken a humane position on the disposal of rats. Atlas has invented a new variety of rat trap that allows for live capture. But even he admits that the gestation period of the species poses a constant threat to the wellbeing of the camp. Campers are in agreement: the city waits for rat infestations to overtake camps, because rats are a commonly cited reason for eviction. The city does not provide rat traps or fly strips for the camp –– camp members have innovated to keep vermin at bay.

A Positive Image

The camp garnered significant support by cultivating a positive public image. Mayor Jesse Arreguín even publicly voiced support for the camp on a number of occasions. In one short statement written by the mayor in 2017, the mayor wrote, “For most of the year, it has been my position that the encampment at HERE/THERE should be allowed to remain. For most of its existence, it has been a well-run intentional community, supported by local residents and businesses.”

And yet, no amount of organization, cleanliness, or public support could prevent the camp from being targeted for eviction. In late October of 2017, BART, whose train line juts out over the camp, issued an eviction notice for Here There.

On October 21, 2017, BART simultaneously posted eviction notices for Here There and for an unaffiliated camp on the east side of the BART tracks. A woman had died at the unaffiliated eastern camp earlier that October. This other camp had also been the source of numerous neighborhood complaints, which mentioned drug use and public defecation, according to Berkeleyside reporting. Despite the complete separation between Here There and this eastern camp, and the vast difference between the two camps in terms of public support and perception, BART decided to issue eviction notices for both camps at once. In response, members of Here There filed a lawsuit against BART.

Toan had joined Here There during the week that the camp received a public notice of eviction.

“So I felt that either I’m gonna stay and stick it out and support, or I’ll just leave, be a supporter on the outside,” he remembers. “After a day, I decided to stay, so we all organized to respond to the city eviction notice. We reached out to attorneys, and people that have knowledge of legal matters, and we asked some people if they were willing to be plaintiffs so we can put a name on to proceed with the restraining order. I was one of the volunteers, along with Clark Sullivan and Jim Squatter.”

Those three FTCFTH members filed for a TRO (temporary restraining order) in federal court to buy additional time to make their case that the camp should not be evicted. In the “Injuries’’ section of the document they wrote: “If plaintiffs are forced to move, homeless people who have no alternate shelter would be forced into the elements without shelter, causing irreparable injury.”

The camp sought “an injunctive relief enjoining defendant and their agents from arresting plaintiffs or removing personal items and/or preventing conduct by plaintiffs to sleep, eat, and maintain shelter at the property commonly known as: 3351 Adeline St, Berkeley, CA also known as the ‘Here-There’ sign.”

A temporary order issued by Judge Alsup on October 25 prevented BART from evicting Here There for a week. On the same day, BART police evicted the eastern camp.

In the end, Judge Alsup did not grant the camp a preliminary injunction, allowing BART to proceed with the eviction. However, Judge Alsup moved forward with a case concerning whether the City of Berkeley had violated the civil rights of First They Came for the Homeless during previous evictions. Despite the absence of any injunctive relief, the federal judge did call for BART to provide the camp with an explanation of when exactly the eviction would occur, so campers could take steps to prepare. Explaining his logic, Judge Alsup said:

“Judges are sworn to uphold the law . . . I wish sometimes the law was more generous to the poor than it already is.”

Regardless of this outcome, many FTCFTH members saw the initial TRO as a historic victory for the camp, and illustrative of unhoused activism achieving success through official pathways.

Camp members left the site on November 4, 2017, before BART could force them off. It was a crisis point for the camp. Both Mike Zint and Mike Lee—another importnat organizer from the earlt days—had just gotten into housing, and both were dealing with the fallout of chronic health issues. The camp split between multiple sites, with members settling at Old City Hall and Aquatic Park, and others remaining yards from the original location, just not on BART property.

Over time, remaining FTCFTH members largely consolidated on a sliver of land directly next to where the original encampment had been—outside a fence that BART erected around the Here There sculpture. And here they stayed. In this location, residents planted roots, many of them building community, stabilizing, and participating in political history for months or years before moving along. It has housed anywhere between 6 and 20 residents at a time. Some former residents have moved to other states. Some have passed away. And some have become housed in the Bay Area, often due to the direct support of members of their community.

More than one member of the Here There camp has described it as “life saving.” The camp has been widely publicized over its many-year history, often for its impressive track record of providing stability and community to residents. Beyond this stability, the camp was instrumental to several former residents securing housing. In fact, many have framed the camp as a form of transitional housing, an important stop along the journey from street homelessness to housing.

“Yes. Here There, the tent encampment on the side of the road, has a greater role in society than just itself,” says Sam. “It helps more than just the singular. It helps the plural. It helps our giant, collective group. You try to take a guy who’s been livin’ on cardboard for two years, has been experiencing auditory hallucinations because of the environment pounding, and try to put him in an apartment…the guy hasn’t dealt with plumbing in a few years. Wiping things down, cleaning things, these are all new habits, relearned habits. It’s a step process.

“…You don’t see people going from doorways to the shelter. They’ll go from a medical office to a shelter. They’ll go from a doorway to a medical office to a shelter. They’ll go from doorway to homeless encampment to shelter. But they’re not going to go from a doorway to a shelter. … [Service providers are] not grabbing people out of doorways. And Here There grabs people out of doorways.”

Finding success through the camp necessarily looks different for different people, depending on their needs and goals. For some, that success took the form of full time housing. For others, it was gaining a greater sense of wellbeing and agency. The immense struggles that residents faced when they entered the camp were varied and highly personal, but in many cases, the atmosphere of the camp afforded an opportunity to confront and address traumas, instability, discrimination, and a wide range of other issues. Striking the requisite balance between protest movement and support system is a challenge that is difficult to fully express, and the camp’s success in doing so is a testament to the brilliance and tenacity of its residents.

Speaking with former residents of the camp who have since moved into housing, one name came up over and over: Joseph Pendleton. Joe is directly responsible for multiple residents being housed: he advocated for each of these people and helped coordinate the complex logistics necessary to get them housing. Joe is a veteran, a former resident of Here There, and a tireless advocate for homeless people. He is unbelievably busy, and can always be found rushing from one crisis to another, helping those who have been abandoned and criminalized.

“I’m 35 years old, going to be 36 on the 24th [of October, 2021], and my medical situation is not that great,” says Ben. “The reason that I really needed housing is because I’m now on dialysis for kidney failure. So that is another thing that I really appreciate from Here There, is that Joseph Pendleton got me housed, which then allowed me to get the medical procedures necessary during my kidney failure.”

Toan’s journey to housing took a different form, but similarly involved the support of community members.

“So some word got out to some close organizers, friends of mine, they found out that I wanted to be inside, so they reached out to other people, and I was offered to live in a house that they wanted to initiate as an activist community house, so I accepted, and also received some support in the payment of it. I’m currently in the house right now, and it’s going well. It’s a different scene, but a lot of things remind me to not take things for granted. There were times when I was outside it would take so much energy to just wash up in the morning, go shower, even pee. You get ready, especially if it rains. When rain’s coming, you have to prepare for it, make sure you have empty bottles you can relieve in, or do hygiene, wash up, empty out your trash, things like that. So now, I just get up, and the bathroom’s just right there. It feels kind of nice: at the same time, there are times when I feel like “do I even deserve this?” This is my thought: I think this is one of the reasons why organizers put in a lot of work, because they want to feel that the privilege that they have, especially unhoused advocates that are inside, it’s worth it, like they deserve it, because of the work they’re putting in. I think I kind of got the sense of that, a bit.”

Kent faced an exceptionally long journey to stable housing, which was critical for him to be able to manage his Parkinson’s. “You’re homeless for five years, your storage fills that up. And I had my stuff in storage for seven years. Seven years of homelessness, until I got to Berkeley. And it took Berkeley five years to get me situated in this apartment here. And I’m very grateful for it, but it shouldn’t take that long, and cost this much. I am blessed, I’m very blessed that I’ve got this apartment. I could stay here until I die. But other people, they just want a place where they can rest their head. And many of the homeless don’t want to deal with the system, which is very widespread.”

Despite the extremely lengthy process, Kent has gratitude for the City of Berkeley workers who assisted him in finding appropriate housing. “I want to say that I thank the City of Berkeley for reaching out and setting me up with a place to live. I appreciate that more than I can say. Some people need it more, just because they got Parkinson’s. That’s one of the reasons they sped it up on me. Because a man with Parkinson’s shouldn’t be living on the street. But there’s a lot of guys that I knew in that camp who died. And they’re off the list now.”

“It was so integral to bringing me back from the environmental pounding that ruined me,” says Sam. “And it does that for a lot of people, I’m not unique on that. It takes people that have been pounded and pounded and pounded by the urban environment, and it stabilizes them enough to get them to the next step. Not everyone’s next step is the same next step, but I’m telling you, the vast majority of people that come out of that camp, the next step is a much more positive step. It’s the next positive step –– it’s not just an encampment on the side of the road.”

Here There would not exist without Mike Zint, Clark Sullivan, Margy Wilkinson, Barbara Brust, Mike Lee, and Michael Diehl. These leaders, advocates, and supporters live on in the legacy of their activism and in the cherished memories of their loved ones and compatriots

Read—and listen to—the whole “Berkeley, 94700” project online at www.berkeley94700.org. Katherine Chen and Henry DeMarco graduated from UC Berkeley in 2021. They met in an English course on the literature of California and devised Berkeley, 94700 as a means of recognizing unhoused communities as neighborhoods. Today, they live and work across the Bay in San Francisco Berkeley, 94700 is informed by extensive archival research, literature review, and commitment to journalistic integrity. Interviews and photographs were recorded and taken with explicit consent, with final editorial decisions made by participating project collaborators. The timeline we constructed of Here There relied heavily on excellent reporting from Berkeleyside, Street Spirit, the San Francisco Chronicle, and other local outlets. We gained invaluable background knowledge for the project through conversations with former and current camp members, and community supporters. Thank you so much to Toan, Ben, Sam, Tim, Alex, Miss Richie, Stacey, James, Kent, Leslie, Julio, Paul, Tony, Dan, and Amanda, for allowing us to record and share your thoughts and experiences.