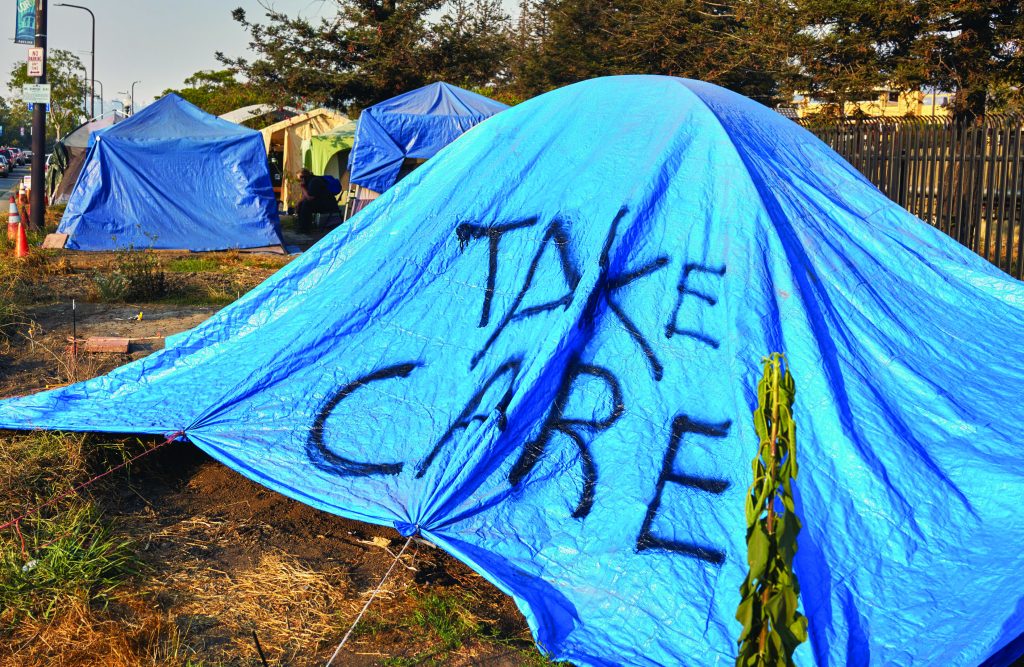

The notion that unhoused people are at fault for their own experience and are inherently bad people is a common thread in American life. It crosses over political ideologies and is a commonly held belief by both liberals and conservatives. It’s rooted in generations worth of (religious and neoliberal) stereotypes, structural racism, and myths about people experiencing homelessness and poverty. “When housed people see homeless people in their day-to-day lives, they can’t ignore the problem,” says Erica Barnett, a long-time journalist in Seattle.

“Proximity breeds empathy in some people, and hatred in others. Sometimes people have empathy at first, then observe over time that the problem continues to get worse and throw their hands up in the air not believing the problem can be solved. This involves a process of dehumanizing other people to some extent. People stop thinking of people experiencing homelessness as actual human beings.”

Blaming individuals for their own homelessness also deflects any sense of collective responsibility for actually solving the housing crisis. Here are some basic ways to think about reframing the conversation about homelessness and housing when talking with your peers, friends and family.

The experience of homelessness is not a reflection of an individual’s choice or character —it’s a circumstance that happens to groups of people when society and governments don’t provide the necessary social safety nets and housing to support people. Millions of people don’t choose homelessness over a safe place to call home.

One of the most fundamental things we can collectively come to understand is that homelessness is not a permanent condition for individuals or families, but something human beings experience over a period of time.

The reasons for people’s homelessness are many. Regardless of people’s circumstances, housing for our most vulnerable citizens is a public infrastructure needed to support a healthy society. We don’t think about things like our transportation systems, bridges, parks, police and fire departments as charity and/or a government hand out. Housing is no different. Everything we do in life starts with having a safe place to call home.

The homeless and housing crisis today is a direct result of the high cost of housing, the lack of living wage jobs, and the lack of affordable housing stock for millions of individuals and families living on a fixed income, or no income at all.

It’s also the direct result of generations (centuries) of discrimination and structural racism that has used housing as a weapon against the poor, mostly people of color.

What keeps us from having the resources to support real housing justice? We must continue to fight for corporate welfare, taxing the rich, and prioritizing housing in our federal budgets.

That’s all great, but what more can I do to support the housing justice movement in my community? This can look like a lot of different things. Maybe it’s working to be a vocal supporter of a local shelter or homeless services in a smaller community that historically has rejected such investments, or being an outspoken advocate for affordable housing projects in your neighborhood and city.

It could be writing your legislators and communicating that housing for our most vulnerable populations is a top-tier issue for you as a constituent.

It could mean researching and financially supporting organizations working towards and engaging in work to advance local and housing justice agendas.

Maybe it’s finding ways to approach or interject and change the hearts and minds of the people in your social circles who may put down people experiencing homelessness or project a false narrative about the larger issue.

It might be introducing your kids (or family members) to giving a donation, or doing volunteer work in the community, to support organizations working to provide people with a safe place to call home.

Other ways you might think about showing your solidarity is by spreading the word about your local street paper (Street Spirit, in the East Bay, or Street Sheet in San Francisco), or housing justice organizations, through your social media network.

You can also buy someone on the streets a cup of coffee and recognize that they are a human being by simply saying hello. I personally carry around a case of water, some hand warmers and a box of granola bars in the trunk of my car to offer people I might see struggling when I’m out and about. This is something any one of us can do.

At the end of the day, the best thing we can do for folks on the streets is to not give up on people. We mustn’t ever give up on the idea that housing is a necessary component of society for our most vulnerable citizens, regardless of the political atmosphere or circumstance we collectively might find ourselves in.

“Offering compassion without judgment is one of the most challenging things you’ll ever do,” the late and great housing organizer Genny Nelson once told me. “Keeping at it day after day, week after week, and maintaining that compassion will be the hardest. The only way to find the space to carry on is to practice non-violence and to believe in love.” It’s true.

Regardless of our own personal experience in life, we all have the opportunity to work towards choosing love and empathy and compassion and non-violence over hate and fear and judgement and exclusion. We must continue our long fight to seek justice in our communities, always. Housing remains a human right.

Israel Bayer is director of INSP North America.