After 125 days, the group occupying the Parker school building to keep it from closing ended their protest and the school board voted on a new use for the facility.

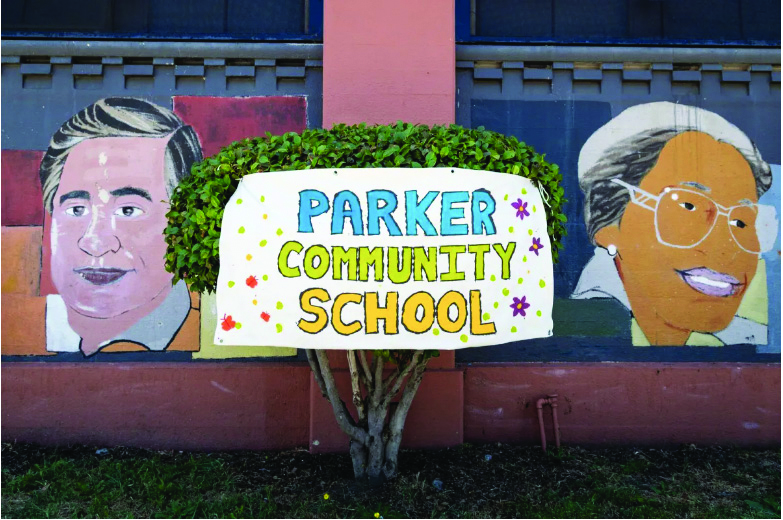

The occupation of Parker K-8 school ended this week, more than four months after two moms and their children vowed to remain at the campus until it reopened. With the support of other school families and community members, they’d built a free summer program at the site, Parker Community School, from scratch. Protesters opposed to the school’s closure had managed to stay at the building since May, despite physical attempts by security officers hired by the district to remove them. The occupation concluded with a vote by the Oakland Unified School District board to repurpose the former school campus as an adult education and community resource center for families in the neighborhood.

While it’s not the conclusion that Parker supporters set out to achieve, it’s a compromise that comes after weeks of negotiations with the school district and outreach to the neighborhood around Parker about what the best use of the building could be, if not a K-8 school.

“Parker will be turned into a building that serves the immediate community: the people and children who live on Ritchie Street, Ney, MacArthur, Parker and the surrounding areas,” said Azlinah Tambu, one of the moms who led the occupation.

“For me personally, the biggest win that came out of this is that OUSD and our community now know that the Oakland Unified School District is not just some board members that sit up there,” said Tambu. “It’s us, it’s parents, it’s the kids, it’s the community, and it’s the board members. And it’s all of us that are going to have to work together to make these things equitable.”

The closure of Parker K-8, a 96-year-old school in East Oakland, was part of a plan that the school board approved in February. Parker, and other schools that are set to close, were targeted for their low enrollments, district officials have said. Parker’s enrollment had been on a steady decline since 2018, when it enrolled 370 students. Last year, it enrolled 227, according to district data. Schools with lower enrollments cost more money to operate than the revenues they bring in per student, putting a strain on the district budget, officials said.

District leaders introduced the plan to close or consolidate 11 schools over two years in January, after receiving a warning letter from Alameda County Superintendent L.K. Monroe saying the district needed to take steps to balance its budget—including closing or consolidating schools—or face financial consequences imposed by the county.

Community Day, a small alternative school for students expelled from traditional high schools, also closed this year, and another, La Escuelita, shrunk from a K-8 to a K-5. Five more schools will close at the end of this school year: Brookfield Elementary, Carl B. Munck Elementary, Grass Valley Elementary, Horace Mann Elementary, and Korematsu Discovery Academy. Hillcrest, a K-8, will become an elementary school.

School closures have become a significant issue in the upcoming school board election, with three of the seven board seats open. Several candidates running have said that the school closures motivated them to run, and would push to have the closure plan reconsidered if elected.

“We have families that had to move to another middle school and today they are still struggling to get the programs for their children that they were receiving here at La Escuelita,” said Max Orozco, a La Escuelita parent who is running for the District 2 seat. “The district never thought of what’s going to happen to those families with single moms that have children in two or three different schools because they closed the middle school here.”

Throughout the occupation, the group at Parker K-8 received support from local community organizations that donated food, money, and volunteers to teach in the summer program. Educators from around Oakland and the Bay Area also pitched in. Some Oakland educators whose jobs were terminated recently feel they’ve been retaliated against for their support of the Parker occupation. The teachers spoke out during a press conference before the school board met on Thursday.

“I want to live in a city where if teachers do have to stand up and fight for the rights of all students to keep their schools, the rights of all students to an equal education, those teachers are not penalized and retaliated against,” said Paloma Collier, the former garden teacher at Markham Elementary who learned late in the summer that her contract with OUSD would not be fulfilled this year.

“I want to be in my garden at Markham with my kids,” said Collier, “a place where we worked for years to turn a pavement-covered playground into a thriving space with art murals, trees, gardens, and an abundance of spaces for children to connect with nature in the middle of an urban area.”

In August, the fight to keep Parker open intensified when a confrontation between OUSD security and individuals at the school turned violent. The district has said it is investigating the incident.

Thursday’s Parker resolution, supported by directors Sam Davis, Aimee Eng, Gary Yee, Kyra Mungia, and Clifford Thompson, will establish Parker indefinitely as a site for adult education and community resources. The district will call for proposals from organizations to provide services like a food pantry, youth programming, cultural programming, or job training.

District 5 school board member Mike Hutchinson and District 3 member VanCedric Williams voted against the resolution. Hutchinson introduced an amendment that failed, which would have restricted the building’s designation as an adult education center to the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 school years, so that the newly elected board could conduct a wider community engagement effort. He also criticized the district’s singular approach to Parker, instead of considering all of the school buildings that are either currently or soon to be vacant as a result of the closures. The board hasn’t come to a decision on how to use the Community Day School facility. “This is not how we’re supposed to do things as a school board and as a school district,” Hutchinson said. “Especially something as important as a permanent use for one of our facilities. This is something we should truly deliberate over with all of the community.”

Parker supporters maintained that if the building couldn’t remain open as a K-8 school, then the community wanted it to be used for adult education.

“Before we got this resolution together, we did something OUSD didn’t do. We went out and door-knocked, talked to the community face-to-face and we asked them what it is that they wanted for this building,” said Rochelle Jenkins, another Parker mom, prior to the board’s vote. “That’s why we’re here today and putting in this resolution because this needs to happen. We’re pleading with you to listen to the actual people who live in these communities, who go to these schools, who feel the impact of school closures.”

Parents want a say in union negotiations

Thursday’s school board meeting was also attended by parent groups that are asking to have input on contract negotiations between OUSD and the Oakland Education Association teachers’ union. The union’s current contract expires on Oct. 31, which means it will begin bargaining with OUSD this month for a new agreement.

The collective bargaining agreement between OEA and OUSD will last for the next three years, and dictate things like working hours, class sizes, performance evaluations, compensation, and more. The two groups pushing for parent input are The Oakland REACH, a coalition of Black and brown parents mainly from the Oakland flatlands, and CA Parent Power, which grew out of another group, Reopen OUSD, that had pushed the district on resuming in-person learning earlier during the pandemic. Members of the Berkeley Parents Union, a group advocating for parents in Berkeley Unified School District, also offered their support.

Parents on Thursday argued that given a larger role in negotiations, they would advocate strictly on behalf of students, and place a greater emphasis on student achievement in the contract. Currently, Oakland community members are able to submit resolutions to the school board for consideration, and it’s up to the board president to decide whether to place them on the agenda. The parent groups are asking that the board consider their resolution at its next meeting on Oct 26.

“Black and brown babies are dying in these streets right now. I’m sickened by this violence and the loss of lives of Black and brown youth,” said Lakisha Young, the executive director of The Oakland REACH. “They need a real shot and the only thing we know is education. Please push this resolution forward so we can have a voice at the table.”

This article originally appeared in The Oaklandside.

Ashley McBride reports on education equity at The Oaklandside.