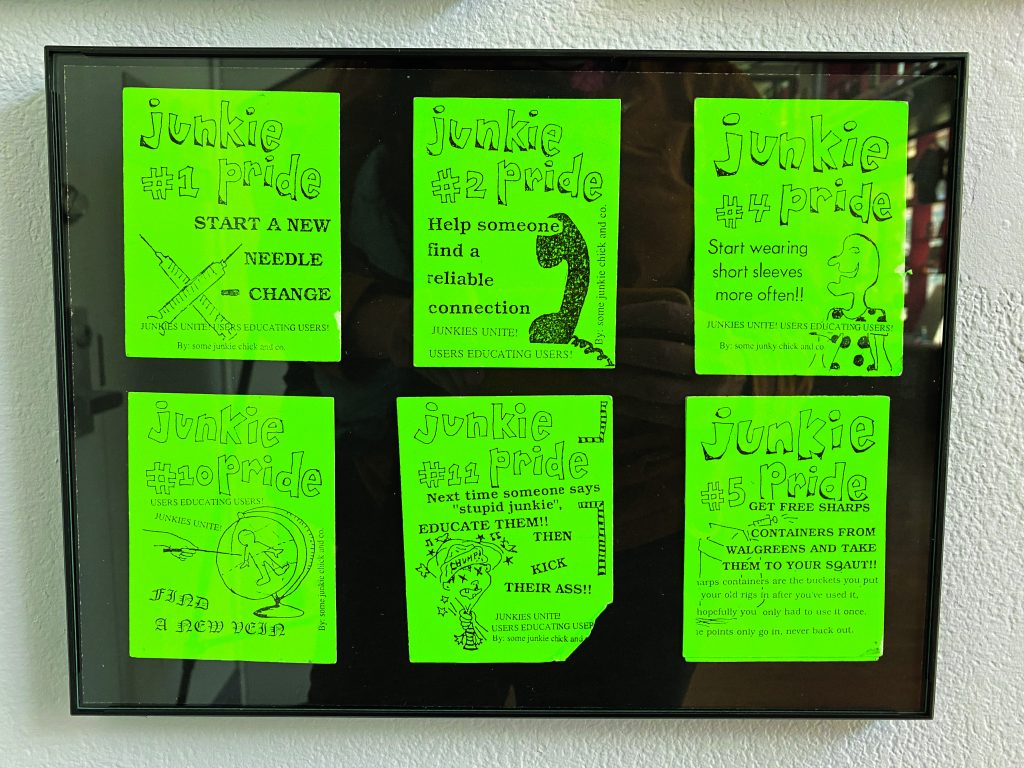

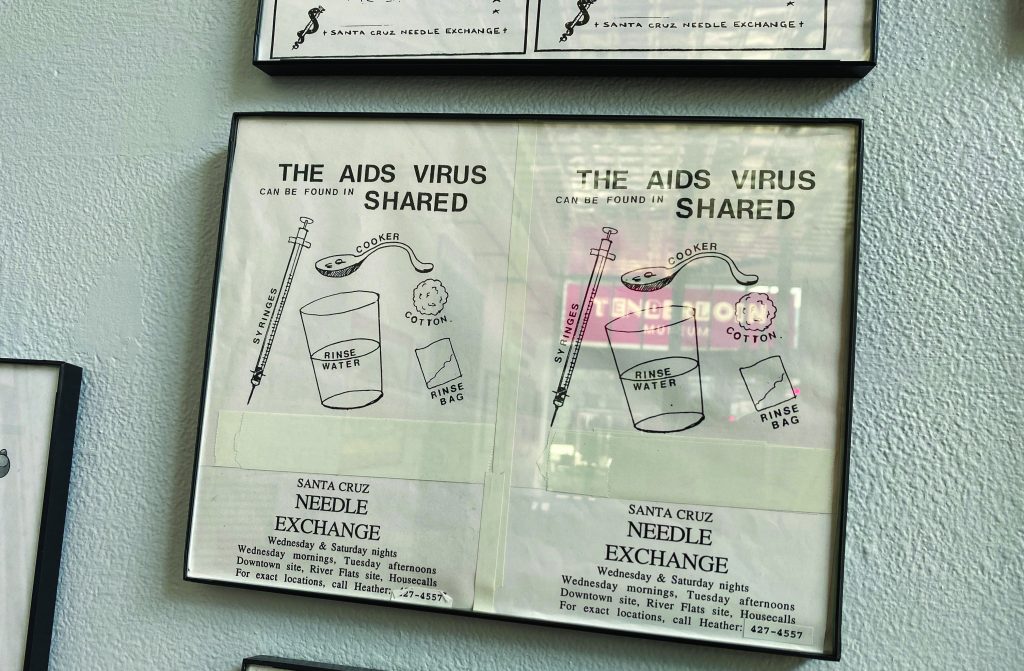

In 1991, people who contracted HIV through injection drug use comprised approximately 30 percent of all AIDS cases reported to the CDC. It was illegal to distribute and possess syringes in most places in the United States. But the first generation of harm reduction activists did it anyway: the stakes were too high. “My Overdose Will Not Be Tragic,” the special exhibit currently on display at the Tenderloin Museum in San Francisco, shines a light onto the radical beginnings of the harm reduction movement—a movement that remains at the forefront of the overdose crisis today. It tells the story of harm reductionists in Santa Cruz in the 1990s through dozens of artifacts. Zines such as junkphood, a trailblazing self-published digest, contain interviews, poetry, art, and essays by young people using drugs.

Flyers show an intimate picture of outreach efforts between people who were taking safety into their own hands as the federal government failed to respond to a mounting epidemic. All together, the archive provides a window into survival strategies and community-building among people who were injecting drugs, uplifting their humanity and allowing them to speak for themselves once more.

“It was really about love, and that’s what this kind of activism was,” says Greg Ellis, curator of this exhibit. “The foundation of AIDS activism and harm reduction was always one of love.”

Wrought by the HIV/AIDS epidemic: the early days of harm reduction in the U.S.

The Santa Cruz Needle Exchange Program (SCNEP) was founded in 1989 by Richard Smith and a group of dedicated volunteers. It became the fourth authorized syringe access program in North America. At the time, the group started out providing services in a parking lot, where volunteers handed out syringes, condoms, bleach, and lubricant. The organization did house calls, an approach that set it apart. Many of the posters and zines on display at the Tenderloin Museum list the landline number for Heather Edney, the organization’s first executive director (and the co-curator for the exhibit). Each week, needle exchange volunteers would make home visits, bringing people sterile supplies, food, or other support when they were unable to leave their homes. Edney visited with them and made a personal connection. She says it was through these interactions that the program developed.

Edney started using drugs in high school and got involved with the needle exchange when she was 19. Before long, she was appointed executive director, and during her tenure, the group expanded its services to 22 fixed sites across Santa Cruz county and two drop-in centers, both aimed at serving young people.

Edney’s approach included services like manicures and pedicures for program participants, as well as wound care and outreach to Spanish-speaking residents of Santa Cruz County. It was also one of the first programs to reach adolescents. This work could only have happened with people who use drugs leading the effort, archivist Greg Ellis tells Street Spirit. “That connection—and having an understanding of the needs of people who inject drugs—is what they were providing. They were rightfully saying, ‘We are the experts,’” Ellis says.

Creative outreach strategies like zines and flyers, drop-in hours for women, childcare, and services for young people were important pillars of their community care. This holistic strategy was pioneered by Edney and her peers. Feminism, and the leadership of young women was central to their work. This mirrored a “seismic shift” that took place in the second generation of AIDS risk reduction, Edney says, a movement whose approaches had previously centered men and often overlooked the needs of women.

This comprehensive strategy widened the scope of the harm reduction movement. Groups like SCNEP focused on the bigger picture needs of people contracting HIV/AIDS, and ultimately, viewed programs like the needle exchange as a way to protect communities against a wider variety of illnesses. Edney and SCNEP undertook the first Hepatitis A & B vaccination campaign in California, partnering with UCSF on the groundbreaking “UFO study” of young injection drug users. (UFO stood for “U find out”—a testing campaign to determine your Hepatitis status).

“Their revolutionary ideas and programs remain the bedrock of harm reduction today,” Ellis says.

However, providing services during this time required determination. It was illegal for Californians to possess syringes without a prescription until 1999. Distributing clean syringes during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, historians say, was an act of civil disobedience. In 1990, there was a wave of arrests of HIV/AIDS activists across the United States who defied the law to distribute syringes, including in Redwood City and Berkeley. Until 2014, Californians could only purchase, sell, provide, or possess a maximum of 30 syringes. Since then, state lawmakers have passed bills every five years to legalize the sale and purchase of syringes at pharmacies for people 18 years and older, and to allow pharmacies to make them available without a prescription. Not all pharmacists are willing to exercise this right, however—and the latest bill will expire in 2026. Amid this precarity, thousands of Californians continue to get sterile syringes from harm reduction programs.

What’s in the exhibit?

The central works of the exhibit are an extraordinary series of zines called junkphood.

“The stories in junkphood come straight from users who exchange syringes at the Santa Cruz Needle Exchange,” a flyer for the publication proclaims. “We, as drug users, are the experts. All of us know bits and pieces of what is safe and unsafe, but because we are shoved underground, there is no way for us to talk about it.”

Still today, services for people who use drugs are often mixed with messaging trying to pressure people to quit. In a 1997 article about junkphood in the Village Voice, Edney is pictured with the quote: “It’s okay to be a proud junkie.”

The zine portrayed a freedom that Edney’s community wanted to see in the world, including the freedom to continue using drugs, on their own terms.

The exhibit takes its name from a piece published in junkphood titled “My Overdose from Heroin Will Not Be Tragic,” by Rod Sorge. In it, Sorge reflects on the stress of poverty and AIDS, and his many painful illnesses, and the delights of living in New York City and finding community with LGBT people all over the world. But the essay explores Sorge’s desire for “ultimate control over his life and death.” It is found within an issue of junkphood titled “The Book of Death 1,” focused on mortality.

The concept for junkphood came from Heather Edney and her friend Matthew Boman. After Boman died, Edney and activist Brooke Lober continued to produce the zines. It was written by young people who were using drugs, for other people using drugs—it published safe drug use instructions and strategies and health information, as well as art and essays. junkphood was printed by the thousands, and had a national and global reach. Issues of the zine even reached Eastern Europe.

Seeing the zines and materials up close, in person, is to see the pieces of tape and painstakingly-cut-out messages, printed and trimmed line by line, and adhered to collages of art, including cartoon characters and animated figures. They’re visually spectacular, with colorful covers. They reflect years of intimate work—including original interviews, poetry, and essays about intense topics, including fatal overdose and close calls.

The materials in the archive belong to Edney, who worked with curator Greg Ellis to put the show together. Edney held onto the archive “through active drug use, homelessness, and into substance use treatment, with her rehab counselor safeguarding it under her desk,” she says.

Ellis is now based in New York and is the creator of Ward 5B, an archive of LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS activism from the 1980s and 90s, named for the United States’ first AIDS ward at San Francisco General Hospital. Raised in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, Ellis contracted HIV and Hepatitis C in the 1980s from injection drug use, and went on to distribute sterile syringes in the peep shows and adult film venues where he worked to prevent transmission during the crisis.

In his archiving work around the AIDS epidemic, Ellis found his archive didn’t contain many materials on harm reduction. Familiar with junkphood, Ellis reached out to Edney online to ask for copies. Edney sent a set to Ellis, and the two began talking weekly.

“It’s nice to have someone who was there and knows the history,” Ellis wrote on Instagram, after a phone conversation with Edney. “There aren’t many of us alive any longer.”

Why now?

Today, distributing syringes is no longer illegal in California, though local needle exchanges have recently suffered political attacks, and the services that organizations provide are limited by the law. In the Bay Area, many organizations, including West Oakland Punks with Lunch, Berkeley NEED, and the HIV Education and Prevention Project of Alameda County (HEPPAC) offer mobile and storefront syringe access, as well as free Narcan—the rescue medication that reverses opioid overdoses by putting a person into withdrawal. The DOPE Project and county public health departments train members of the public on reversing overdoses with Narcan, and community members in the Bay Area reverse thousands of overdoses each year. But fatalities continue to climb, as people who use drugs face problems with fentanyl and synthetic opioids contaminating the supply of many non-opioid substances—and the supply is unregulated, because drugs are still criminalized.

SAMHSA, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, just launched its first-ever grant program for harm reduction and announced it will issue funding for 25 syringe access programs, including three in Southern California. The move is historic: It means federal funding for syringes. Still, the government has declared it will prohibit the use of these funds for the purchase of glass pipes for distribution, dismaying some harm reduction activists. Distributing clean glass pipes is important for preventing injury, toxic fumes, and virus transmission.

But the ongoing overdose crisis, and struggle to provide resources for the people who need them, is why the archive is still relevant today.

Sorting through Edney’s possessions ahead of the exhibit brought up “a lot of grief,” Greg Ellis reflects. “It’s going back to that time and touching the past in a real way, those wounds. But it also highlights the love that was shared.”

Ellis and Edney hope that the archive will bring together harm reduction activists, past and present, to pass along information and serve as an “open-source lifeline” to a new generation taking the baton.

“Where is the positive in all these stories?” activist Edith Springer wrote in an introduction to junkphood in 1997. “The positive is in the telling and the listening. We may be a long way from making things better, but this is the start. We come out of our closets and we let the healing light in. Read these stories; let the light in. Talk about them. Let more light in.”

“My Overdose Will Not Be Tragic” will be on display through August 27, 2022. The Tenderloin Museum is located at the northeast corner of Eddy and Leavenworth in San Francisco, open Tuesdays-Saturdays 10AM-5PM. Admission to the overdose exhibit is free, though admission to the rest of the museum is $10, or free on Wednesdays for Tenderloin residents. The materials in the exhibit are not available to pick up and thumb through — but interested readers can find scans of issues of junkphood at Edney’s website, myoverdosewillnotbetragic.com.

Ariel Boone is a freelance journalist and reporter for KPFA Radio in Oakland, California. Ariel previously worked at Democracy Now! in New York.