On the 50th anniversary of the Attica prison uprising in New York, incarcerated journalist Kevin Sawyer reflects on the history of police violence in America

Fifty years ago, the national discourse on state-sanctioned police violence against a Black man rallied around a man named George. That history can’t repeat itself because it has not ended. It continues where the point of focus is typically centered on local law enforcement who feign the assignment of judge, jury, and executioner.A cop’s bullet—or knee—can, and often does, render a clinical death. But their pen, if used maliciously to write a false police report, arrest warrant or search warrant fastened to perjured testimony, effectuates a civil death through imprisonment. The pen or the sword, or in many cases, the gun, is not an unimaginable leap for a rogue cop. The evil trinity of police, prosecutor, and prison that Black men face all begins with a cop.

“Defund the police” is the latest cry for reform to restrain the pervasiveness of evildoers who work in law enforcement. Remember Mark Fuhrman from the O.J. Simpson trial in 1995? Does anyone believe he was the first or that the likes of him no longer exist?

What about those who work or assist those who work inside prisons and various states’ departments of corrections? Turn back 50 years again to recall the 1971 Attica prison uprising in New York. We know how that ended. Thirty-three unarmed prisoners and 10 guards and civilians were massacred. According to author Heather Ann Thompson, “128 men were shot—some of them multiple times.”

Attica corrections officers, the Bureau of Criminal Investigation, New York State Police, local sheriffs’ deputies and park police descended on the prison. In addition to the firearms already at the prison, 217 shotguns were passed out to the troopers along with 33 extra rifles that were sent to the prison.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR) officers have “peace officer” status similar to city police, sheriff’s deputies, and the highway patrol. If anyone believes CDCR officers don’t kill with impunity, then turn your attention to San Quentin Prison on August 21, 1971, when George Jackson was assassinated for an alleged escape attempt.

Need more proof? In the 1990s, officers at Corcoran State Prison customarily set up fights between inmates in security housing units and placed bets on who would win. To break up the fights, officers used deadly force. One victim killed during that time was Preston Tate, a Black man. Let’s call him “George” as well. And then, as at Attica, what followed is the concealment of the crimes by the evil trinity that works in tandem with shield state evildoers and other authorities from impending civil liability.

In 2019, the CDCR had 9,692 use-of-force incidents, according to a July 2020 report by California’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG). Of those, 2,296 were monitored by the OIG.

“In 51 of the 2,296 incidents (2.2 percent), officers did not adequately articulate an imminent threat, leading us to question whether the force was necessary,” the OIG report stated. “(I)t represents an increase compared with our last report,” which reflected 1.5 percent of the incidents.

If the culture of so-called “blue lives” is ever going to change, then officers employed with the CDCR can’t be let off the hook either. They should not be allowed to hide, out of sight, behind prison walls, because their violence is also real.

As demonstrations and protests bring greater awareness to police violence in America, it’s important to realize that an officer’s misdeeds do not end at the prison gate. Sometimes they flourish in carceral environments because too often what happens there is overlooked, until it bleeds back into our communities.

People will always remember where they were when they watched Minneapolis police extinguish the life of George Floyd in eight minutes and 46 seconds. They’ll remember the videotape beating of Rodney King too. Half a century after George Jackson was murdered, with so many Black lives slain since then, it’s wise to remember that everyone is a potential George until wanton police violence against all people is stopped.

This article originally appeared in San Francisco Bayview.

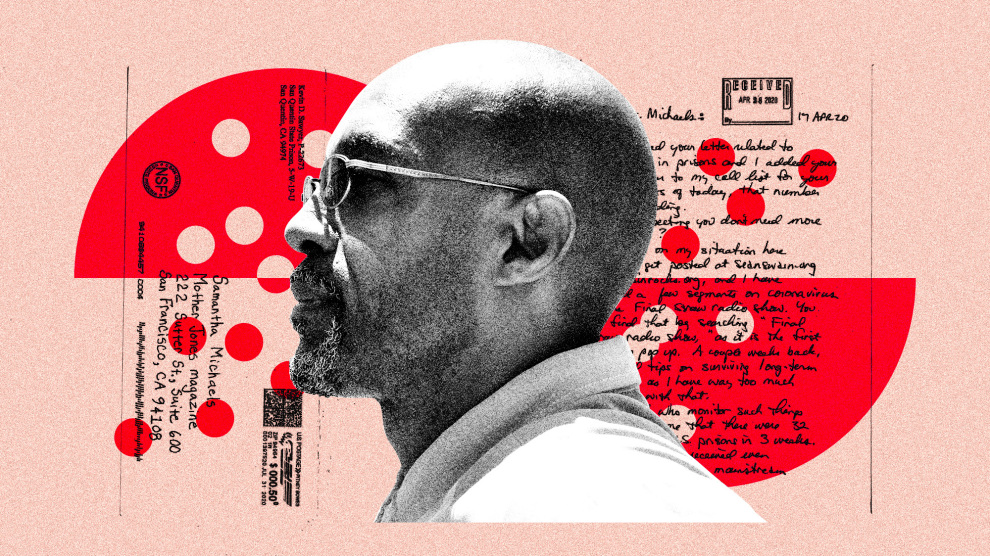

Kevin D. Sawyer is a San Francisco native. He is the Associate Editor for the San Quentin News, an inmate run newspaper produced out of San Quentin State Prison. He is a 2016 recipient of The James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism.