The plan was to pair a bicycle race with the distribution of essential winter gear and food to Oakland area unhoused communities. Unfortunately, rainy weather put a damper on the cycling portion. But that didn’t stop a handful of dedicated volunteers from spending a cold, wet day delivering as many of those supplies as they could—by car, rather than by bike.This event, dubbed “the Giving Spirit,” was the brainchild of The Village, a grassroots advocacy group in Oakland, and the Cardboard & Concrete unhoused artists collective—a group of unhoused artists from Berkeley and Oakland. The All Souls’ Episcopal Parish in Berkeley, which regularly embarks on projects to support unhoused people, provided supplies and food. Members of the church and the East Bay community at large provided additional warm clothing and other donations. Volunteer events like this help fill the gaps that are left by local governments and official service providers, which are stretched too thin to cover the immense need that exists in the Bay Area’s homeless community.

“Thank you from our hearts to all of the organizations and individuals that have so generously seen a great need and have been doing the action work to fill a great void,” said an encampment resident named Kata Ellsworth, while volunteers distributed food and donations around her.

Needa Bee, who is herself unhoused and founded The Village in Oakland, oversees the provision of housing support and twice-weekly food deliveries to Oakland area homeless encampments. She explained why they wouldn’t let the downpour cancel the event completely.

“Being unhoused, you’re already in the elements. If anything, that’s even more reason to bring people hot meals, because people are going to be cold and miserable out in the rain. The weather won’t stop us from doing what needs to be done. That inconvenience is part of daily life,” said Bee.

Multimedia journalist and Cardboard & Concrete Collective member Yesica Prado lives in her vehicle. One of the lead planners for the event, Prado said they intended for the bike event to take place two months ago, but it was postponed several times. When asked why a bike race rather than simply delivering goods by car, she offered two reasons.

“Many members of the Collective are bike couriers,” she said. Unhoused people don’t have addresses and delivering by bike courier is the only way you can deliver things directly to their hands, she explained. The bike couriers suggested bringing in outside people and turning it into a community event. “Anybody can ride a bike too, you know? So we wanted to invite anybody and anyone to do it,“ she said.

Berkeley’s All Souls’ Episcopal Parish has a long history of supporting the local unhoused community. When Bee and Prado arrived to pick up donations, Deacon Dani Gabriel showed them three discrete piles of supplies, specifically designated for three encampments. Rector Phil Brochard explained that they had first done a needs survey of the three encampments to find out what they needed, and then members of the church filled those needs. These included warm clothing and blankets, waterproof containers, tarps, toothbrushes and other hygiene items. By targeting the donations in this way, he said, “We don’t end up with a lot of ‘junk for Jesus.’”

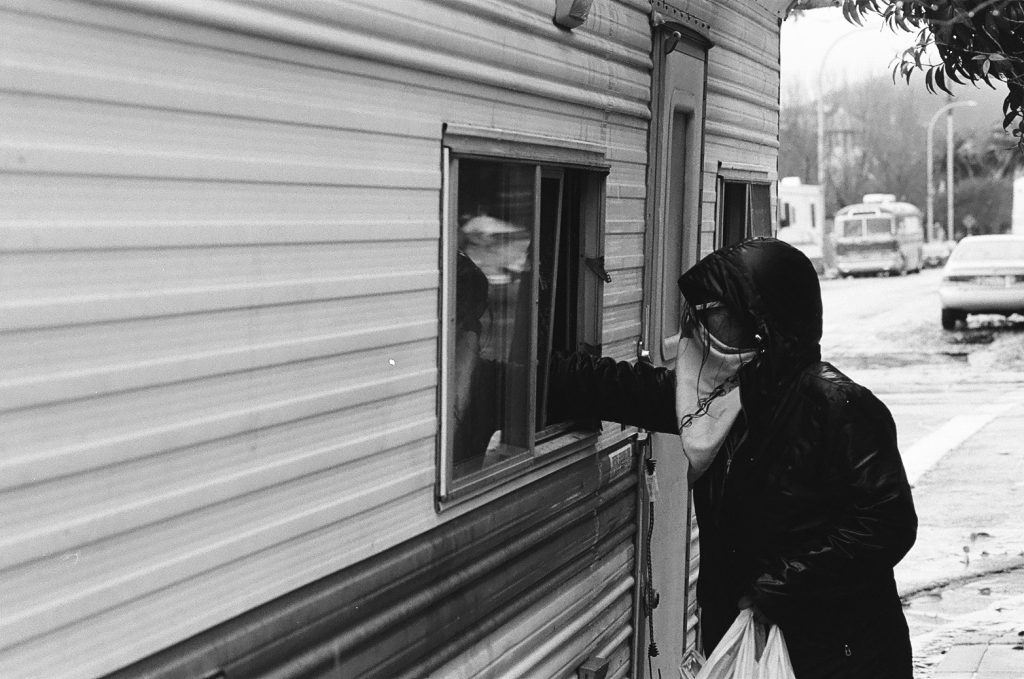

At a Berkeley encampment, the volunteers were met by three additional church members. Jeff and Cathy Goshorn and their fellow parishioner, Pat, went from RV to RV handing out an entire SUV-load of jambalaya, packed in individual meal-size bags. Kata Ellsworth—who sometimes refers to herself as the “camp mama”—said, “Living without a home is very challenging, but it can be done with dignity and compassion, cleaning up after ourselves and having consideration for everyone, including surrounding businesses.” Kata advocates for her encampment and maintains a space she calls “Harmony Garden” within the industrial area her community calls home. It includes a covered seating area and social space, surrounded by meticulously cared-for plants and flowers. She added, “To receive the amazing outreach that we have seen here in Berkeley brings hope and a feeling of being seen and valued. With that renewed hope comes a sense of compassion and unity….What you do touches lives and makes a difference!”

But the need is great. According to the January 2019 Point-in-Time Count, Oakland had an estimated 4,017 people living on the streets, in tents, or in vehicles—a 47 percent increase since 2017. Nearly two years after the most recent count, given the additional turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, homeless advocates believe there may be as many as 10,000 homeless people in Oakland, spread across at least 45 large encampments and dozens of smaller ones.

On any given day, grass-roots organizations and private citizens can be spotted handing out food or other donations on the periphery of many of these camps, especially as the weather turns colder. Bee acknowledged the “wonderful spirit of generosity around the holidays,” but highlighted that the assistance given to homeless encampments on Thanksgiving and Christmas can lead to unexpected problems and asked that people be more mindful. “What people tend to do is drop off boxes of food and drive away. These donations often result in piles of boxes and trash after the holidays, which can bring in rats and roaches. This leads neighbors to complain about the trash they blame the unhoused for having created which, often then results in the city harassing unhoused folks, Bee said. That’s in the best-case scenario, she added. “In the worst case scenario, [the encampments] get bulldozed.”

There are ways that we can all contribute a little something, even if it’s just time, said Prado. “If you don’t have things, we always need volunteers, you know? So there’s always a way to help,” she said.

Bee said she hopes residents of the encampments see their actions as empowering. “Folks know that we’re not helpless; that we actually can help each other. And I think it also helps change the stereotype, for housed folks to realize that we’re not helpless.”

Thomas Brouns is a documentary filmmaker and student at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism. He has served four overseas tours as an American diplomat and is a retired U.S. Army officer.