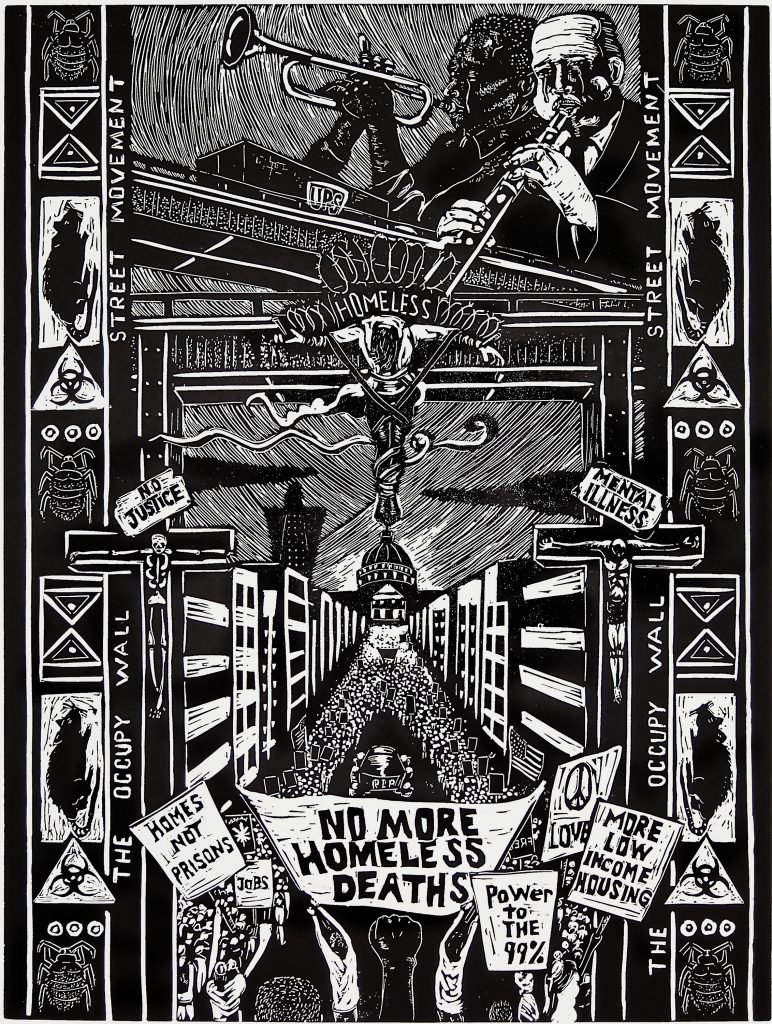

Almost prophetically, Ronnie Goodman made an etching of people marching in the street and carrying a banner that reads “No More Homeless Deaths,” one in a myriad of drawings, paintings and engravings he produced. After a lifetime of creating art while homeless or incarcerated, on August 7, Ronnie Lamont Goodman was found dead in his tent outside the Redstone Building in San Francisco’s Mission District, where he intermittently stayed and stored his drawings and illustrations. He was 60 years old.

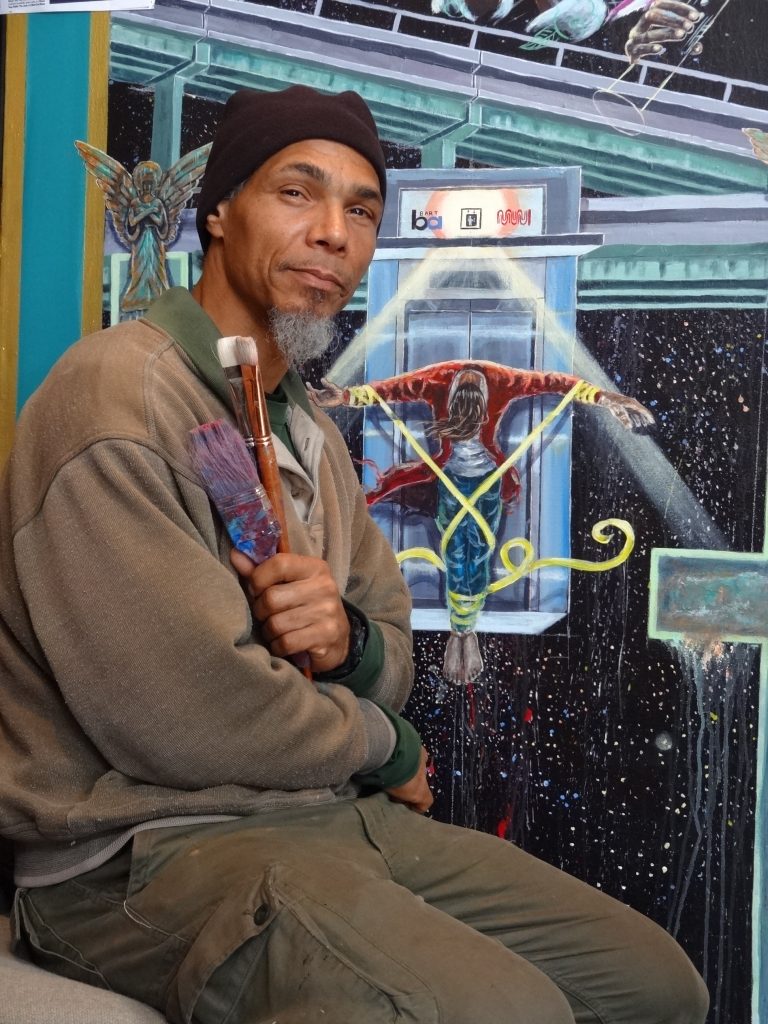

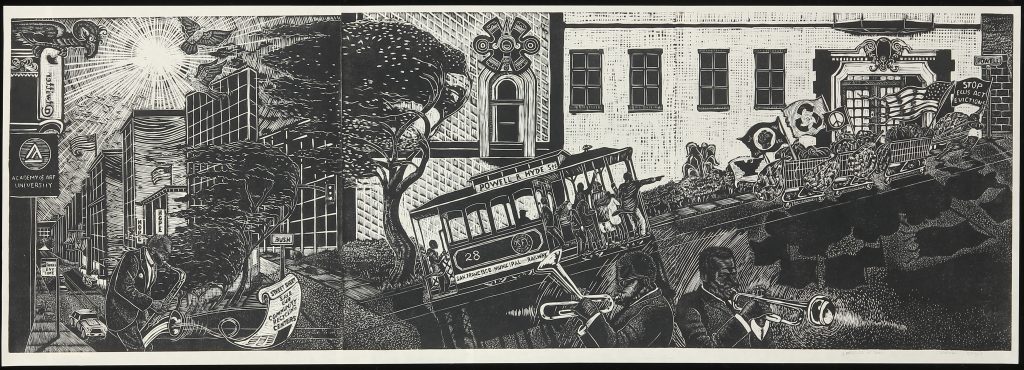

Goodman was a self-taught artist whose work was prominently displayed in venues ranging from the San Francisco Public Library, to MoMA PS 1 in New York, to the pages of Street Sheet and other homeless publications, to the office of then-San Francisco Supervisor, now Mayor London Breed.

As prolific as his artistic output was, Goodman also lost many of his works to sweeps conducted by San Francisco’s police and public works departments. In one such incident in 2017, police detained him for vandalism and ticketed him for illegal lodging when he tried to prevent a Public Works employee from seizing 50 linocut drawings and the tent where he was sleeping.

In recalling that and similar incidents for the Stolen Belonging project in 2018, Goodman described his passion for creating art and the desperation he felt when the authorities deprived him of his handiwork and the tools he used to devise it.

“And they took at least over a period of a year, or two years, probably 400 different art items that I need to have,” he said. “What I mean by items, drawings, sketches, drawing books, sketchbooks, painting, paints and supplies and inks and stuff like that.

“And right now, it’s like I’ve got to go beg for help to get some items so I can create. Because that’s what I like doing. I like drawing, I like creating on the spot. But since I don’t have that stuff, I’ve got to go out and be like everybody else. I’ve got to panhandle for some money in order to get something to eat, or in order to get some art materials, because of what the police and DPW are doing.

“They’re making my life very, very horrendous, and they’re making it so anti-productive that it’s insane. Because I’m like, ‘hey man, I’m an artist, and this is how I make my living.’ That’s my survival. It’s like, y’all work, and this is your survival. This is my work, this is my survival.”

A self-described “hippie child,” Goodman was born on July 25, 1960 and grew up in San Francisco’s Haight and Fillmore districts where art surrounded him and fed his muse.

He started drawing at the age of six, and was inspired by the political activity and vibrant social experiment of the 1960s. The countercultural movement in the Haight was in full swing; redevelopment in the Fillmore uprooted mostly Black residents.

At the same time, Goodman fell into addiction and was imprisoned for burglary. During his eight-and-a-half years in San Quentin State Prison, he made greeting cards and drew portraits in exchange for coffee, cigarettes and anything that could be bought at the prison’s commissary.

When he was paroled in 2010, Goodman continued to devote himself to art and a long-distance running regimen. In 2014, he raced the San Francisco Half-Marathon as a fundraiser for Hospitality House, a homeless service organization that runs a community arts program. Through running the 13.1-mile course and auctioning off one of his paintings, he raised over $40,000. In 2016, he ran the half-marathon again, benefitting the Redstone Building, which provides space for community-based organizations on 16th and Capp streets.

The Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP) was another beneficiary of Goodman’s work. Art Hazelwood, the homeless organization’s self-described “minister of culture,” said Goodman’s images amplified the message of social justice movements.

“In recent years, Ronnie Goodman has been a strong visual voice for WRAP,” Hazelwood said in 2015. “He has made powerful pieces about homelessness.”

Those pieces often appeared in Street Sheet, the newspaper that the Coalition on Homelessness publishes. In a 2017 article he authored, Goodman advised artists: “Stay creative and stay focused and don’t try to overthink anything. Come from the heart and how you feel. Try to step back a few steps and listen to other’s opinions and reflect on it. But don’t stop, don’t ever stop creating.”

He was survived by Tanya Goodman, his wife; Nicole Goodman and Piara Goodman, his daughters; and Marinte Goodman, his son. Ronnie Goodman, Jr., another son, died in 2014.

This article originally appeared in Street Sheet.

TJ Johnston is the Assistant Editor of Street Sheet, San Francisco’s street newspaper.