Activist and former Berkeley mayoral candidate Mike Lee died at age 64 of complications related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in mid August. Housing activists and many people experiencing homelessness across Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco reported sadness at his loss and admiration for him in the wake of the news. “He was an incredibly compassionate yet strong individual” said Paul Kealoha Blake, who has done homeless advocacy work in Berkeley for over two decades.

Starting in the mid 2010s, while Lee himself was unhoused, Blake would meet with him and unhoused people regularly at the McDonald’s on Shattuck and University Avenues in Berkeley to strategize about how to advocate best for unhoused people’s rights in general and to help them access services. Many of the people Lee met were unhoused youths. He would help them secure shelter through local non-profits and city programs.

“All of the kids knew him,” said Blake. “He knew the ropes and provided them with realistic inspiration. It’s one thing to talk to a kid and tell how they’re gonna have housing but it’s another to talk to a kid and say ‘It may be months before you get housing. It doesn’t matter. We’ve gotta do it anyway.’”

According to Blake, Lee went to that McDonald’s because he knew it as a place where unhoused people hung out.

“We can’t expect vulnerable people to track us down,” said Blake. “That was definitely where Mike Lee was at. You go where people are at to talk to them, intellectually, emotionally, psychologically, as well as physically. He was incredible in that way.”

Oakland native and unhoused resident Preston Walker, better known as Pastor Preston, reports that Lee regularly came to homeless evictions in Oakland, sometimes deep into the eastern part of the city that sits farther away from Berkeley. He would help people stay as safe as possible and keep their possessions, which were under threat of demolition or disposal by the Oakland’s police and department of public works. Health problems forced him to use a cane or a wheelchair but he still navigated public transportation to be present at evictions.

“It’s easier to talk to someone that’s unhoused when you’re unhoused,” said Walker, who remembers Lee as relating well to those being evicted, many who were, like Lee, also older and/or disabled.

Lee knew what it was like to be evicted as an unhoused person from his experiences in Berkeley and he stood up for his rights.

“He always had that warm smile but he never backed down to nobody,” said Walker.

In March 2017, Lee sued the City of Berkeley, claiming the city violated his constitutional rights in October 2016 during an eviction by destroying his property. Also in 2016, Lee made his most public fight for unhoused rights when he ran for Berkeley Mayor.

“The idea was never that he was going to be mayor,” said Blake. “The idea was that he would bring issues to the campaign that would not have been brought up.”

Lee used his platform to bring issues of housing and homelessness into Berkeley’s political and public discourse. According to Blake, who worked on the campaign, he and Lee had frank discussions about how it was impossible for him to win as he was not “running against a person but a machine.”

“He wanted to be mayor,” said Blake, but Blake described Lee as a person who was “not naive” and knew what was possible in the context he was working in.

Rejecting respectability politics and the desire to appeal to everyone, Lee’s campaign, much like his friends described his personality, had a cantankerous humor to it. Lee and his supporters put signs and stickers throughout town that read “Old Bum for Mayor.”

He also used his platform to be serious. During a speech on November 7, 2016, election day, Lee described a brutal attack he alleges Berkeley police executed against unhoused residents three days prior. During the same speech, he said “Homelessness describes an economic condition, not a person.”

Lee’s mayoral run brought him into mainstream Berkeley public’s eye but many activists in Berkeley and Oakland first met Lee in 2014, during the Berkeley post office occupation. He, along with Walker, Mike Zint and several other unhoused people, lived in front of the post office at 2000 Allston Way for months in 2014, at times gathering large crowds to protest the sale of the building to a developer, Hudson McDonald, who USPS was negotiating a sale with. In September of that year, after massive public pressure, the city declared a Historic Civic Center District Overlay, which protected the post office that had been built in the 1800s from being sold.

“He was always there with a take no prisoners attitude about homeless people having to stand up, be militant, speak for themselves, and not just be fodder for these nonprofits”

Lee had deep roots in the Bay Area. He grew up in Portland but moved with an uncle to Daly City at age 13, then moved to San Francisco at age 17. San Francisco activist and poet, Sarah Menefee, remembers Lee when he was “handsome and skinny,” and first met him in 1987. Her memories show that he was involved in activism and fighting for the rights of unhoused people at least since he was in his early 30s.

“He was always there with a take no prisoners attitude about homeless people having to stand up, be militant, speak for themselves, and not just be fodder for these nonprofits,” said Menefee.

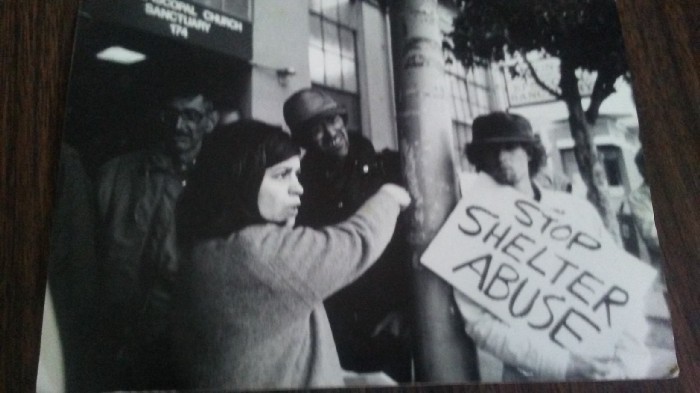

In the late 80s, while he was living in SRO [single room occupancy] housing in San Francisco, Lee and Menefee helped organize an SF chapter of the National Union of the Homeless. Through the union, they organized shelter strikes with unhoused residents who they recruited out of food lines. Then they would stage protests outside of homeless shelters they felt were mistreating unhoused people. Menefee attributes this public pressure to the Coalition on Homelessness eventually creating rights of appeal which made it harder for non-profits to kick unhoused people out of shelters for infractions or accused infractions they had before been powerless to challenge.

In the 90s, Menefee lost track of Lee and said she heard he moved to Las Vegas. Over two decades later she reunited with him at the post office occupation.

In September 2018, Lee secured housing through the Homeless Coordinated Entry System, a program he had long been critical of. Menefee suspected that the City of Berkeley sheltered him thinking “it would shut him up.”

But soon after being housed, he publicly claimed in an article in The Daily Californian that he suspected his prominent status is what got him housed and that he worried others would not get the same opportunity.

“We may have won this battle, but we haven’t won the war yet,” Lee is quoted saying in the article. “So, it’s a start. One down, thousands more to go.”

Lee kept showing up to evictions and organizing with unhoused people. He also shared his apartment with other unhoused people, allowing them long stays.

Up until his final years Lee sought out unhoused people to organize with. After seeing Oakland resident Derrick Soo doing his broadcasting on Facebook about his situation experiencing homelessness in deep East Oakland in 2018, Lee tracked Soo down.

Impressed with what he saw in the small community where Soo said people got along well and took care of the space despite a lack of city services, Lee helped the people there get better tents and make connections with local food banks. He named the community the 77th Ave Rangers and got people in the surrounding area and the media to visit the site to, according to Soo, “see who the homeless people are and not just their imagined stereotype.”

Eventually Lee and Soo were able to successfully get portable toilets, weekly trash pick up, and an agreement with the city for the police and the department of public works to leave the site alone.

“For a while the city had even hired a housing coordinator for us,” said Soo, “but that didn’t work out because there’s no housing to coordinate the homeless into.”

Lee acted as a mentor for Soo. For about a year, up until about a month before Lee’s death, they would message each other every morning.

“After our first meeting sitting down, eating lunch together, he said ‘you know, you should run for mayor’,” said Soo.

After a discussion involving more encouragement from Lee, Soo was convinced. He plans to run for Oakland Mayor in 2022.

This article originally appeared on Medium.

Zack Haber is a journalist and writer who lives in Oakland.