Broderick Crawford, known as BC, was 15 years old when he started coming to The Island in about 1966, passing through or hanging out. “It’s like a garden to me,” he explains.

Once, BC says, he saw Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver lead a Black Panther Party march down Adeline Street past Driver Plaza with a hog, taking it all the way to the doors of the Berkeley Police Department. He also remembers when The Island, also known as Driver Plaza, had a speakeasy. He points to a tree in the middle of the tiny park, a triangular patch of city land squeezed between Stanford Avenue, Genoa Street and Adeline Street, and shows Street Spirit where the entrance used to be.

The speakeasy is gone today. In its place is a newly installed, community-funded portable toilet and hand-washing station, which The Island’s visitors have sought for years. But now, developers and some neighbors want it removed.

The people who use the space during the day, including housed neighbors, unhoused people, and even volunteers, needed a Porta Potty there, and Oakland-based homeless advocacy group The Village pooled donations to pay for one. But since its arrival in May, the toilet has come under attack.

It’s not the first time that advocates have raised funds to install a portable toilet here. On at least two occasions in the past, the city has forced a Porta Potty in the park to be removed. But this time, with grassroots pressure, and under a new city homelessness administrator, government officials seem to be holding their fire. It’s here to stay, for now.

The park, The Island, the plaza

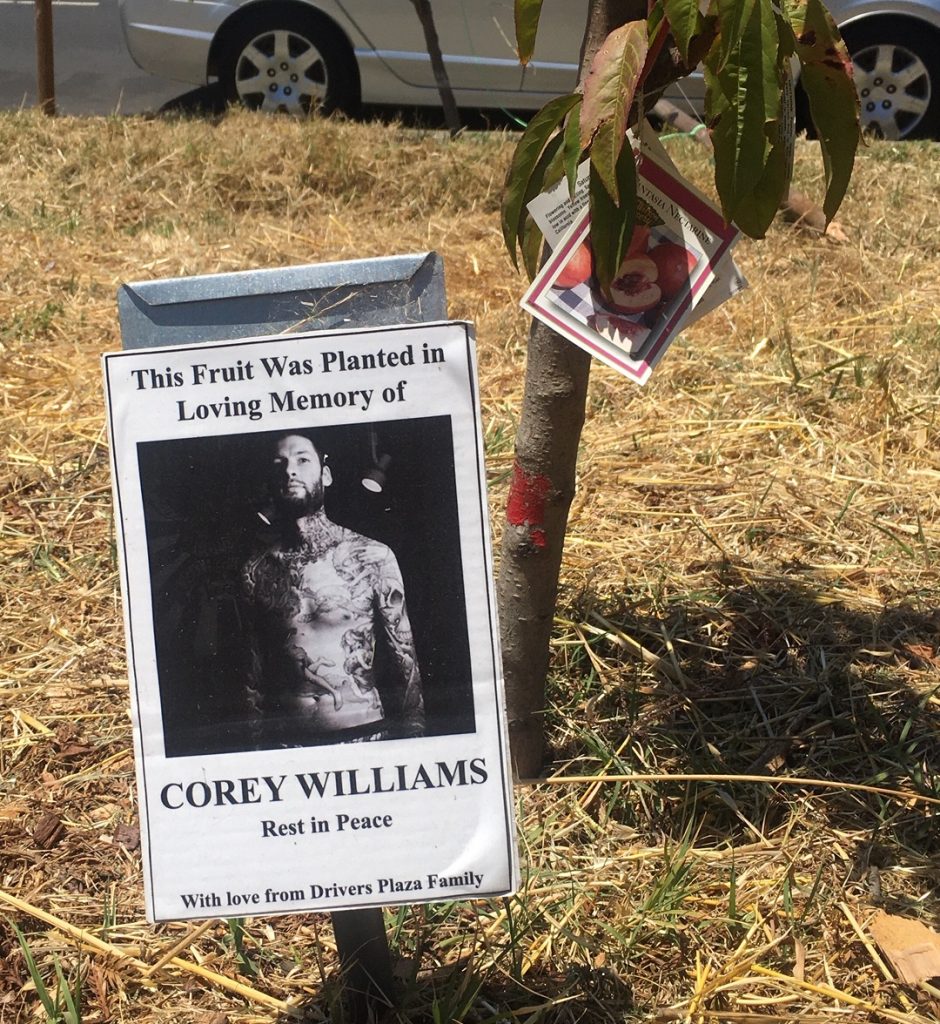

Much of Driver Plaza is paved. It’s also a bicycle through-route, with patches of grass, benches, and a sheltered bus stop for the transbay F line. On the south end, activists have planted a memorial grove of fruit trees, each bearing a placard in honor of a departed community member.

On Tuesday, July 14, 2020, fifty people gathered at Driver Plaza for a speakout to defend the park and its toilet. The park looked spotless: Trash was picked up, and a volunteer had power washed the space in anticipation of the event. Protesters stood far apart, wore masks, and observed several minutes of silence for George Floyd. Longtime park visitors gave speeches, while volunteers distributed herbal remedies for immune system strength and handed out groceries to housed and unhoused people in the park.

Those gathered said more is at stake than a toilet: it’s about the right of poor Black seniors to exist, thrive, gather, and pee, in a historically Black neighborhood that has forced out its Black residents and seen sweeping gentrification.

“They’re trying to take away Porta Potties, but really what they’re trying to take away is all these beautiful people who are originally from this neighborhood,” said a young scholar with Decolonize Academy, a radical school connected run by POOR Magazine and activist Lisa “Tiny” Gray-Garcia. “It’s not like the Porta Potty is their main concern—their main concern is, they’re trying to take away the basic human rights of everybody here, after kicking them out of their houses. We’re not gonna lay down like that.”

Another park user, Skits, who is 15, told Street Spirit he thinks Oakland is “trying to kick every poor person out” to make Oakland more like San Francisco. “We’ve been tired,” he says.

According to census estimates, Black residents made up 42 percent of the neighborhoods surrounding Driver Plaza in 2010. In 2018, that number had fallen to 29 percent.

A 2012 report by Urban Strategies shows hundreds of properties in the neighborhood were foreclosed on between 2007 and 2011, and over a hundred were purchased by real estate investors and speculators. During the foreclosure crisis, this neighborhood was among the most affected in Oakland.

Here, as happened across the country, Black homeowners were stripped of property. Black families were forced out, newcomers came in. The cost of a studio apartment in the neighborhood is now $2,396, according to real estate website Zumper.

Aunti Frances’ fight

“Aunti Frances” Moore is a fierce community leader, a former Black Panther, a former Street Spirit vendor, and the park’s recognized leader. She founded the Self-Help Hunger Program, which distributes food each Tuesday at Driver Plaza. At the rally on July 14, she stood in front of dozens of bags of groceries and fresh food for the community. “I learned from the Panthers, using food as a tool to organize,” she announced to the crowd.

One of the longtime park users, a videographer named Vida, says the park’s “whole atmosphere” has changed a lot over the past six years. “It’s changing toward the positive because of Aunti Frances.”

But Aunti Frances has had to fight for this park and the community members who use it. As early as 2014, she paid out of pocket for a portable toilet to be installed at Driver Plaza. It was removed by the city of Oakland’s Public Works department. With support from Decolonize Academy, Aunti Frances held a “Where can we pee?” protest at Oakland City Hall and wrote letters to then-Mayor Jean Quan. The city did not respond.

The community’s claim to the park came under attack again in 2016, when food justice collective Phat Beets built a cob oven on The Island, and the Oakland Public Works Department dismantled it.

Then in May of this year, The Village used community donations to rent a new Porta Potty and handwashing station and install them on The Island. But opponents of the toilet began calling Honey Bucket, the portable toilet operator, to complain.

“No matter what we do, it seems the have-mores aren’t pleased,” Aunti Frances told the crowd on July 14

Honey Bucket gave the names of the unhappy callers to The Village, which holds the account for the toilet. Street Spirit has determined that the list of names includes two staffers for Oakland’s Public Works department.

Back-and-forth with the city

Margaretta Lin is the executive director of Just Cities, a justice-focused policy and planning organization. But she used to be the deputy city administrator in Oakland, and she intervened to support The Village when she heard the city wanted the Porta Potty moved.

“I think it’s completely ridiculous and inhuman for the city government to be trying to remove an essential service and a basic human need during the twin pandemics of covid and racism,” Lin told Street Spirit. “I contacted my former colleagues to find out what was going on. Is the issue that there’s no permit? We can deal with that. What’s the problem, right? Let’s fix it, because this is an essential service.”

But she received mixed messages. The Department of Transportation confirmed that they were initially “trying to get it removed.” But the Department of Health and Human Services sent both Lin and the Department of Transportation an email indicating they supported the Porta Potty.

Emails from Human Services on July 7 and July 8, shared with Street Spirit, confirm that the city planned to order Honey Bucket to remove the toilet the following week. “We thought it prudent to inform you of the removal plan,” Oakland community housing services manager Lara Tannenbaum wrote in an email to advocates, including The Village. “Hopefully this gives you time to relocate it yourselves if you would like to.”

That week, Lin says she received a phone call from a contact at the city, informing her that it planned to remove the toilet under pressure from the office of city councilmember Dan Kalb.

Protesters at Driver Plaza on July 14 were particularly critical of Councilmember Kalb, whose district encompasses the park. They hung a banner reading, “Dan Kalb and Libby: Can we come over and use your bathroom? Then leave ours alone,” and made phone calls to Kalb’s office during the rally.

Kalb told Street Spirit that his opposition to the Porta Potty at Driver Plaza is rooted in his belief that it would be of more use elsewhere. He pointed out that there are dozens of encampments in Oakland that are not serviced by the city—meaning that Oakland does not provide trash pick-up, or toilet, hand-washing or shower services. He believes The Village should put the Porta Potty in one of these communities.

Kalb insisted that community activists are exaggerating about the importance of the toilet and making a “mountain out of a molehill,” saying that his actions on this were “twisted” to paint him as anti-homeless, which he says is “BS.” Kalb says his staff exchanged emails with the city administrator’s office about the Porta Potty to suggest it be moved elsewhere.

“I want to help more people. I want to help people who need a Porta Potty the most, the ones who are living at a homeless encampment,” Kalb said. “And the reality is the majority of people gathering at Driver Plaza are not homeless.”

But seniors at the July 14 rally say the Porta Potty is desperately needed in the park for people on-the-go, regardless of housing status and especially during Covid-19. One told the crowd, “As an old guy, we have to pee a lot. The restaurants won’t let you use the bathroom, the libraries are closed up. You have to use a park, and you can get busted and end up arrested for indecent exposure, all because there’s no fucking bathrooms for old people to go to.”

Needa Bee from The Village says Kalb’s argument erases the unhoused people who do use the toilet, and the park. Needa received emails from the Human Services department in June asking her to move the Porta Potty to a curbside community on Manila Avenue, two miles away, arguing that location had a greater need. “They are denying the existence of Black unhoused folks,” Needa told the crowd on July 14.

The city eventually paid to place its own Porta Potty on Manila Avenue, Kalb says. He told Street Spirit that Porta Potty and handwashing stations are in high demand during the coronavirus pandemic, and said he is aware of some companies who are out of those rentals.

Three hours after the park protest began on July 14, Oakland’s Homelessness Administrator, Daryel Dunston, sent Margaretta Lin an email saying that the city is taking “no action” to remove the Porta Potty at Driver Plaza.

He wrote, “There appears to be some miscommunication—and for that I sincerely apologize—but I can confirm that neither the Public Works Department nor the Department of Transportation have contacted the vendor (HoneyBucket) requesting the removal of their unit. Furthermore, this location has not been scheduled for any action by the Emergency Homelessness Taskforce (EHT).”

For now, this seems to be the final word—and Councilmember Kalb does not intend to challenge the decision.

“I’m very busy with a lot of important things,” Kalb said. “That was their decision, and I said that’s fine. If something changes, if it’s not getting serviced, if something happens, hopefully not, then the city would start initiating.”

What’s next for the park

Skits, the 15-year-old who passes through Driver Plaza often, told Street Spirit that in the future, he’d like to see a real, brick-and-mortar bathroom and formal resources in the little park, including a healthcare center and basketball hoops.

Aunti Frances said she’d like the city to allow her to turn on the water in the park, to be able to irrigate the memorial orchard and provide more services to the people who pass through.

Street Spirit also asked longtime park user BC what his vision for the space would be. “It’s happening now,” he said, raising his arms and gesturing to the intergenerational and multi-racial crowd gathered to defend the land.

Ariel Boone is a freelance journalist and reporter for KPFA Radio in Oakland, California. Ariel previously worked at Democracy Now! in New York.