In April, Berkeley observed the 50th anniversary of the iconic People’s Park. Whether it will be a celebration or a memorial is yet to be decided.

The Park has a rocky history. In May of 2018, UC Berkeley announced plans to bulldoze the park, and build student housing on the lot where it now sits. But the present is not the first time that the university decided to build dorms on its lot.

In the 1960’s, they were raised the money to develop the plot of land they owned between Haste, Bowditch, Dwight Streets just above Telegraph Avenue. They bought the houses from all the people who were living there at the time, and took the ones from the homeowners who were not willing to part with their homes using the process of eminent domain. They demolished all the houses on the land leaving a very unsightly vacant lot. However, those planned dorms were never built.

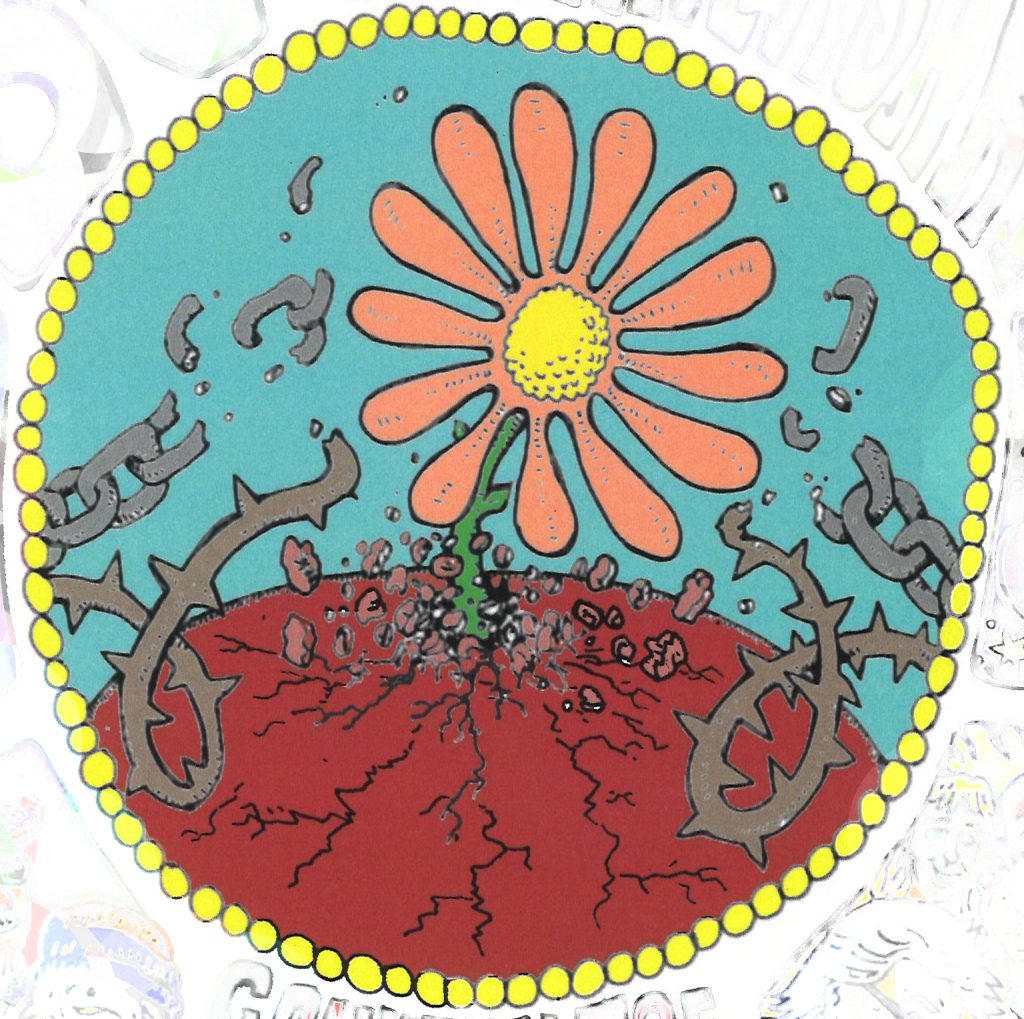

Instead, a call went to the community to come out and build a park. People came. They cleared the land and put down grass and began planting flowers. For a short time, the Park was at peace, university officials promised to talk to the Park supporters before making changes. But this all changed on May 15, 1969, the day that is remembered as Bloody Thursday, when the Park became a battleground.

It started off with a rally at Sproul Plaza, which moved toward the Park where it was met by Berkeley police and the California highway patrol sent by Governor Ronald Reagan. The crowd of protesters grew as did the police who began using tear gas and more lethal weapons.

National Guard troops were sent. More than one hundred people were wounded, one person was permanently blinded and a student, James Rector, was killed.

For more than a week the slaughter continued. Finally a sort of peace was declared. The university kept the 8-foot-high fence they had built and put in a parking lot. It took years of protest and negotiations before the university removed the fencing and more years to remove the concrete parking lot.

But even though the university ultimately made peace with the people, it is clear they had—and continue to have—a different agenda for the Park. For 50 years Park activists have been devoting countless hours to creating a place to fill the needs of people in the community. But they have been finding over and over again that too often the improvements or additions they made during the day were undone by university employees at night.

People have always flocked to the Park to work on particular projects. With an eye to the future, one group got together in 1974 and planted trees appropriate for the site. There were groups that focused on decorative plantings, a group that concentrated on California natives. Fruits and vegetables to be shared were a major enterprise through- out the years. The vegetable garden at the western end of the Park is still struggling to survive. But it has never been easy. The university does not have the same vision. Water supply could not always be depended on. The gardeners brought tools and built a shed to store them at the site, but quickly the shed and tools were removed.

In 1989, the Catholic Worker towed a small trailer to the Park and set up the Peoples Café, which served breakfast. People loved it, but the university immediately had it hauled away. Now, using a portable folding table the Catholic Worker still serves Sunday breakfast in the Park. Food Not Bombs has been serving a vegetarian meal at 3:00 five afternoons a week since 1991.

In spite of continued requests for a green bin for compost, that has never happened. After the meals the food scraps and paper plates are deposited in trash barrels that go to the landfill, though they should be composted.

A free box for donations of clothing and useful items was set up at a convenient location on the Haste Street border of the Park. It remained there for a time, and then it was removed. The Park activists built a new one, soon it was gone again. This happened a number of times. Each time the activists built a stronger model. Finally they gave up when their latest effort, a structure made of steel and concrete, was taken. Since then then donations are left on the ground at the Park’s entrance.

Public bathrooms accessible during open hours are required in a in a park. Disgusted with the unsanitary port-o-potties placed there, the activists began laying the foundation for a proper bathroom in the Park. No surprise, a university crew came

in the early morning hours and destroyed it. The same thing happened several more times until the university changed course and built a proper bathroom. Maintenance of the bathroom has been sporadic, but the mural on the outside wall provides a bit of class. The dedicated Park activists recently gave it a touchup.

The activists intended the Park to be for all people, including children. Swings and a slide, sets of games and play equipment were donated and

a children’s playground was set up. It was maintained for many years. People would bring their children to play and at the same time they could have an afternoon meal or get needed food from the garden. Gradually the playground fell into ruin, equipment broke and disappeared. There’s nothing left of it now.

Then there was the battle of the volleyball courts. In the summer of 1991, protected by a dozen policemen, a UC crew built a volleyball court in the center of the Park. No one expected it, no one wanted it, no one used it. There were protests and demonstrations. Someone appeared with a chain- saw and cut down one of the posts holding the net. The story spread, but hardly anybody played volleyball. This went on for six years and finally ended with the university backing down. Eventually the courts were taken down and the people brought the land back to life.

Looking back over almost 50 years, Peoples Park has always been true to its name, it is a park belonging to people, all people. People of every age and class are in some way connected with the Park. There are the activists for whom building and maintaining it is a satisfying activity, there are those for whom it is a sanctuary when they are homeless and have no place to go but the city streets, and there are people who are simply look- ing for a place to sit under a tree with a book or at a table with companions and play a game of chess.

The Park has lived on because it is needed by people: elderly and longtime residents as well as the homeless. Its story has spread well beyond Berkeley and its spirit will never die.

Lydia Gans is a writer, photographer, and activist who lives in Berkeley.