At 4:30 a.m. on Thursday, May 15, 1969 250 California Highway Patrol officers arrived at newly constructed People’s Park, while a helicopter buzzed overhead. They cleared a few people who were sleeping on the fresh sod and put up a chain link fence. As the sun rose, Berkeley’s newest green space, a symbol of an alternative vision of society, was enclosed behind a perimeter of state police officers.

It was not a sight students and activists would accept quietly. By noon, a large rally was underway at Sproul Plaza. The mood was heated. Law student and ASUC president-elect Dan Siegal made a speech comparing the University’s destruction of South Berkeley to America’s destruction of Vietnam. When he declared, “Let’s go down and take over the park!” the police shut off his mic, but it was too late.

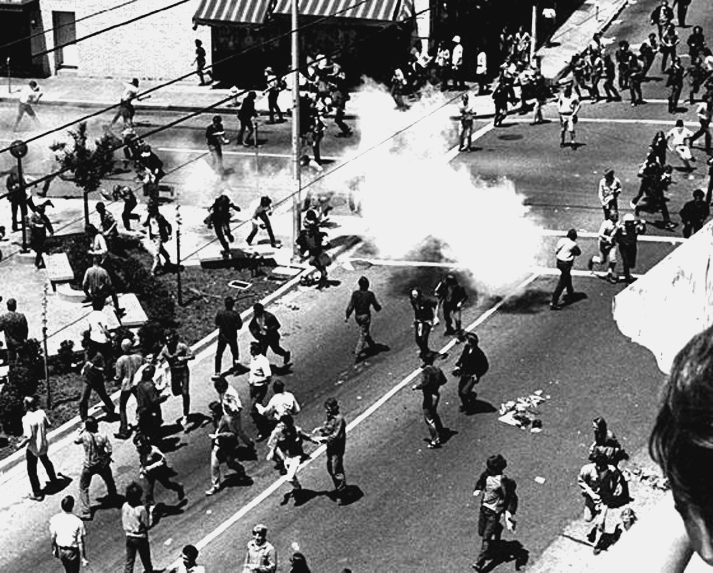

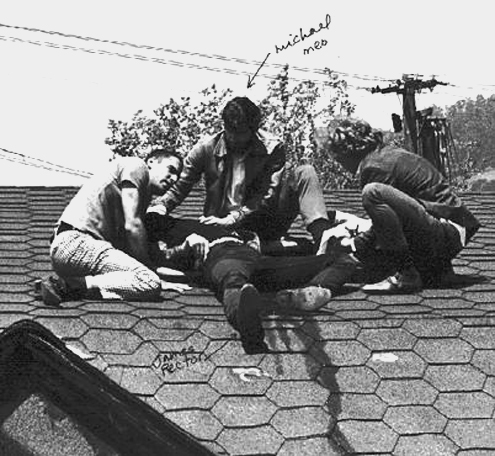

The crowd, chanting “take the Park!” was already headed down Telegraph. Police stopped the protestors, numbering somewhere between two and six thousand people, before they could make it to the Park. As the crowd scattered, some protestors began committing acts of vandalism, smashing the windows of a Bank of America branch, opening fire hydrants, and setting a car on fire. Others got on the rooftops along Telegraph, from where they threw debris at the police.

Michael Delacour, one of the founders of People’s Park, believes that the people who began the violence were “Reagan provocateurs,” young men he didn’t recognize from his years of activism in Berkeley, throwing “two- or three-inch pieces of cut steal” at both police and protestors. Governor Rea- gan himself maintained that the Park was construct- ed “as an excuse for a riot”—indeed, Stew Albert, a close friend of the revolutionary prankster Abbie Hoffman, had previously mused that the conflict over the park would “suck Reagan into a fight.”

However it began, the violence was clearly asymmetrical. Police responded to the debris with tear gas and pellet guns loaded with birdshot. Eventually, some officers switched to more dangerous buckshot.

All told, 110 protestors were shot, and one, James Rector, was killed. May 15th is now infamously known as “Bloody Thursday,” which was in fact the first in a series of incidences of state violence related to the park. The Battle of People’s Park is one of those events that can be identified as the beginning of the end of the 60s. But in reality, the battle is part of a much larger historical arc, that’s still bending to this day.

While it may have been built by flower children, People’s Park was a child of urban renewal. In the 1950s and ‘60s, the University of California had grand plans to redevelop large swathes of the south side and Tele- graph Avenue. The plans were not simply about creating new university facilities, but were explicitly in re- sponse to the alternative, low-income community that was blossoming in the neighborhood.

“I want the university to tear these houses down to the ground and build parking lots, tennis courts, anything” said California Assemblyman Don Mulford in 1967, referring to the eclectic early 20th century houses in the south side that provided cheap housing for hippies as well as low-income students. “We must get rid of the rat’s nest that is acting as a magnet for the hippie set and the criminal element.”

Between November 1967 and December 1968, the university began demolishing the houses on the block bounded by Haste, Dwight, Telegraph, and Bowditch streets. With no immediate plan for the space, it became a muddy, rutted parking lot.

So starting on Sunday, April 20, 1969, a group of volunteers took

over the park. They laid down sod, planted trees, and built a fire pit. Children played in seven-foot-tall, hollowed out letters spelling the word “KNOW,” while adults distributed cuttings from a couple of boiled pigs. The atmosphere was “joyous and sexual,” Delacour recalled. “It was spring time!”

Activists sought university or city approval for the Park at least four times in the early days of its existence, but each time were rejected by bureaucrats fearing the wrath of Governor Reagan, who had been elected on his hard line against hippies and did not want to legitimize the movement.

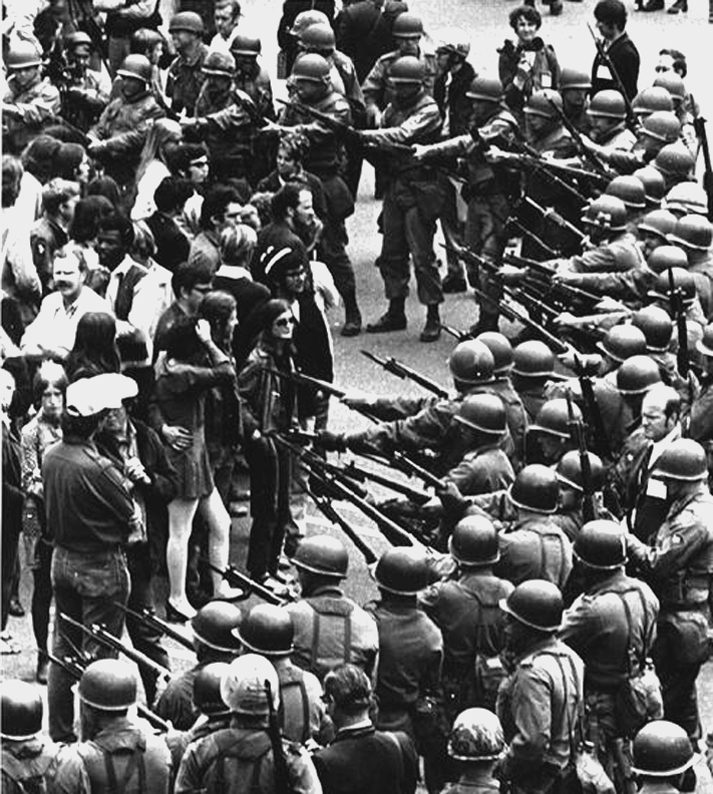

It was this political philosophy that turned the Park into a battleground. On the evening of May 15th, after the initial bout of violence had sub- sided, Governor Reagan deployed the National Guard to Berkeley at the request of Mayor Wallace Johnson. They stayed for 17 days. The military occupation of the city only solidified the events’ connection to the Viet- nam War in the minds of activists and observers around the world. During the state of emergency, police imposed a curfew between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m., and prohibited more than three people from congregating at any hour. Guardsmen stopped and frisked people at random, confiscated cameras, and in a few instances smashed the windows of parked cars of people they didn’t like. “It was like you’d see in some sort of totalitarian country,” Berkeley student Jim Chanin told the AC Register.

On May 20, at one of the many peaceful, illegal protests that were held during the occupation, police sealed protestors into a confined area around Sproul Plaza. A military helicopter arrived and sprayed the crowd with CS, a gas that had been used by the military in Vietnam and was eventually outlawed under the Chemical Weapons Convention. While non-lethal, the chemical can lead to near instantaneous vomiting and diarrhea. People on campus and as far away as Cowell Hospital and the Strawberry Canyon pool, were affected.

In another incident, police and the national guard arrested 482 people, some of whom were trying to establish a new People’s Park on a BART-owned vacant lot, and bused them to Santa Rita Jail. Sheriff John Madigan threatened the detainees at Santa Rita that there are “a bunch of young deputies back from Vietnam who tend to treat prisoners like Viet-Cong.”

And so they did: Male arrestees were forced to lie face down in gravel for four hours without being able to move, let alone use the bathroom. Many were arbitrarily beaten or prodded with guns.

These incidents, and the absurd inconveniences caused by the military occupation, turned the tide of public opinion in Berkeley and around the country in favor of the protestors, as evidenced by sympathetic coverage in local papers and numerous national magazine reports. ASUC held a referendum which showed that 12,719 students favored the Park and 2,175 were opposed, in the highest turnout election in ASUC history.

On May 25, the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, activists held a massive peaceful protest. Iconic images from the day show young women sticking flowers in the bayonets of the National Guard troops, who were themselves growing weary of the occupation. While the Park remained off-limits, protestors planted flowers at the base of the chain-link fence. The Park would remain fenced until May 8, 1972, when protestors tore it down following President Nixon’s decision to blockade North Vietnam.

It’s a harrowing origin story for a little patch of green space. But People’s Park has always been more than just a park. It was a radical experiment in user development and civil disobedience that very quickly revealed just how threatening the social vision of the hippies—once finally put in practice—was to the powers that be.

“What the Human Be-In in San Francisco of 1967 had been for one day, what the Woodstock Festival in upstate New York in early 1969 had been for a weekend, People’s Park was meant to be for keeps,” Theodore Roszak, the originator of the term “counterculture,” wrote in From Satori to Silicon Valley.

And in many senses, it has remained such a place; a relic of the 1960’s counterculture, reflective of that era’s ideals and its naiveté. But if People’s Park is an ongoing utopian experiment, it’s also one of very few enduring monuments to that tumultuous time in American history, to the epic ideological tug of war between liberation and regulation, self-expression and state power, that continues to this day.

Benjamin Schneider is a freelance journalist living in San Francisco.