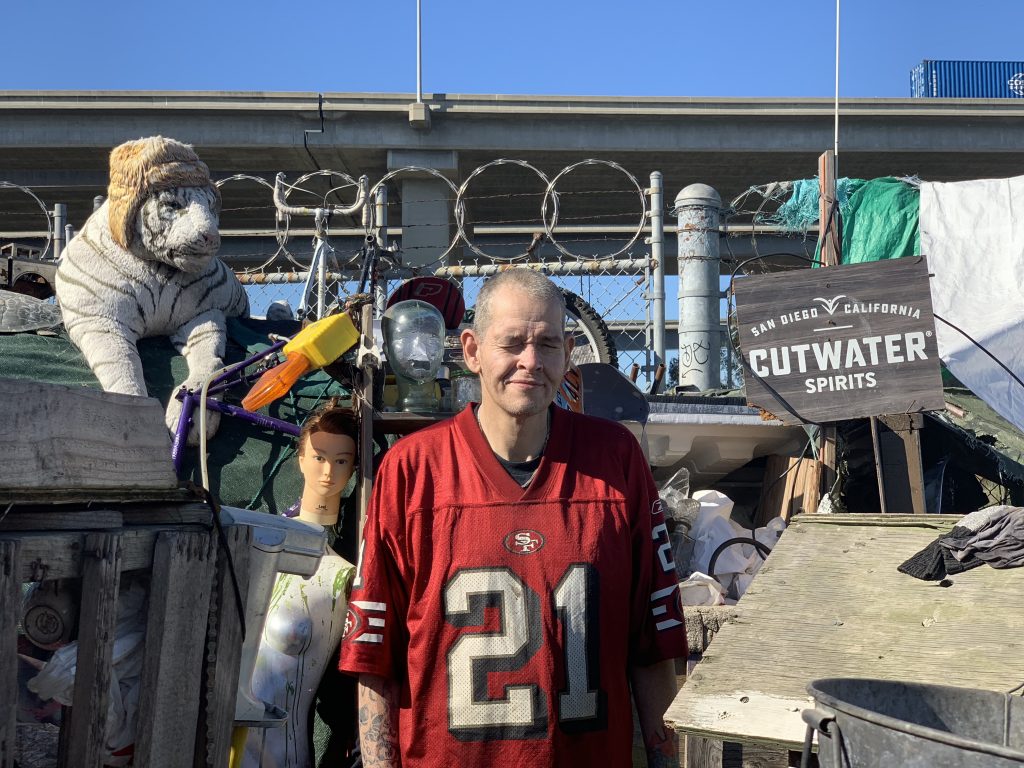

Tim Nishibori disappears into the depths of his cramped but cavernous shack, which sits near the end of a strip of trailers and tents in West Oakland. His gray pit bull, Lady, plays hostess, entertaining me with enthusiastic kisses by the makeshift gate as Nishibori rummages around. Eventually, he emerges with two chairs, and invites me into his home. “Sorry about the mess,” he says.

The décor includes an enormous stuffed white tiger sporting an Ushanka hat, several mannequins in varying stages of dismemberment, and signage from a fancy San Diego distillery. A salvaged shelving unit houses a small collection of succulent plants and a swarm of goldfish milling about in a crowded glass bowl.

Five years ago, Nishibori was evicted from his two-bedroom apartment in the Ghost Town neighborhood of West Oakland for drug-related reasons. Since then, Nishibori has called the encampment home, not counting a brief stint several months ago in an East Oakland apartment provided by Operation Dignity—a non-profit that helps connect homeless people with both transitional and permanent housing.

“It was in deep, deep East Oakland, at 100th and MacArthur,” Nishibori recounts. “East Oakland is different. They’re harsher, stricter—and they don’t like white folks.” Nishibori, who is half Japanese and half white, gave up the apartment after a month to move back to West Oakland—the neighborhood that feels like home.

“When I came to the East Bay, I went through trials and tribulations with the gangs here [in West Oakland],” Nishibori says. “I earned my respect, so I’m accepted over here, and I don’t have problems. This is where I’ve made my ties.”

Nishibori grew up in Boston. His father was a successful businessman, and the Nishibori family enjoyed a privileged lifestyle: they skied in the Alps every winter and traveled around the world, even living in Italy for some time.

“I’m not mad at my family,” Nishibori says. “They gave me a good life—I was one of those children that had everything. It took me a long time to realize that.”

Nishibori moved to Oakland in 1997 following his family’s move to the Bay Area in 1992. However, despite their physical proximity, they have not kept in touch. As Nishibori explains, bad choices he made early have had a lasting impact.

“It doesn’t matter where you’re from; you can always end up out here,” he says. “As a kid, I had no aspirations. Well, jokingly, I wanted to be in the Mafia. I didn’t have much going on. I dropped out of high school and got involved with drugs.”

At 49, Nishibori is still caught up with drugs. But he has begun to make some changes.

“I don’t deal drugs anymore, because it’s hitting my conscience too much,” Nishibori says. “I’ve watched my friends use over the years, and I’ve watched them die. And my time is coming up too, so I’m done facilitating those choices. I’m done making it easier for my friends to kill themselves. I won’t have that on my hands.”

Nishibori is also attending to his own health: After years spent subsisting on inexpensive junk foods, Nishibori is trying to eat more healthfully. But fruits and vegetables are much pricier than ice cream and Nutty Buddy bars—a burdensome expense for someone who has renounced drug-dealing.

“I’d rather be poor than guilty.”

“Since I gave up dealing drugs, I’m poorer than ever—I’m trying to buy real groceries now, and man, it’s expensive,” he laments. “But I’d rather be poor than guilty.”

He has also dramatically reduced his drug usage, and, at the prompting of an old girlfriend, he is considering getting completely clean.

“I’ll be 50 in June,” he says. “I’m thinking about quitting for my birthday. If I can, that’s what I want to do. If I can’t…well, but I think I can.”

Nishibori is still working with Operation Dignity to find a house closer to West Oakland. He figures that if he can get back indoors, he may be able to find a job.

“But for now, I need a side hustle,” Nishibori says. “I want it to be legit. I’m not going to break the law; I won’t steal from nobody. I’ve tried charging Bird scooters with my generator.” (Bird scooters—the dockless electric scooters on the streets of the East Bay—need to be charged every day. Individuals can earn money by taking on this task and releasing the scooters back into the wild fully charged.)

“Then, the other day, some guy hit the railroad tracks [on a Bird scooter] and stacked,” Nishibori says. “I ran out and helped him, gave him some hydrogen peroxide and some toilet paper, bandaged him up, and sent him on his way.”

This sparked a new idea: “There’s one spot on the railroad tracks over there that will pop your tire every time,” Nishibori says, gesturing. “I hear five or six blowouts every day. I’m thinking about making a sign: ‘We’ll change your tire while you wait! $20.’”

Julia Irwin is a writer, a recent UC Berkeley graduate, and a soon-to-be law school student.