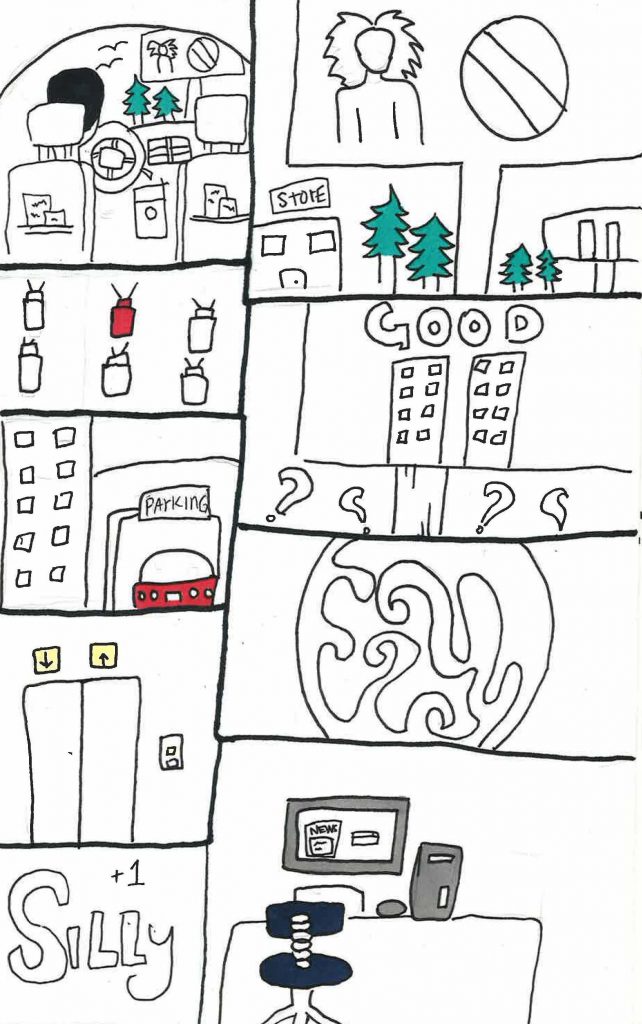

In a car, on my way to work, I saw the ever-present, giant, illuminated billboards along my flight path, displaying Albert Einstein with a “No” symbol (red circle with red diagonal line) superimposed. My eyes kept going there. I worried about looking so much—would I get in trouble for

that? We weren’t supposed to “not look at them.” Yet, looking too much was worrisome. But making an effort not to look at them was also worrisome. I wanted to make sure that no one could question my loyalty. And, I believed that I should never have reason question it.

My car perfectly maneuvered among the other cars, all of which flew in formation along the prescribed route. If a car malfunctioned, (which I’d never seen, but supposedly had happened) it would not crash into the side of a building because all cars were to take the approved route. On another billboard, the video of the collapse of the two World Trade Center buildings, repeated, and it alternated with the word “GOOD!” in giant golden letters.

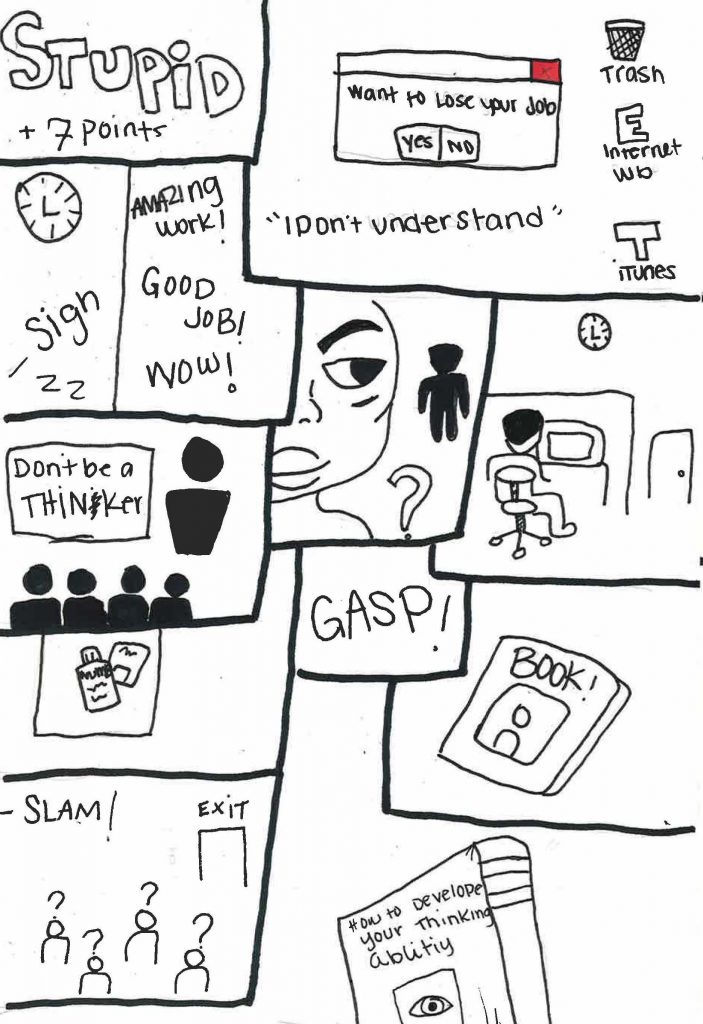

What did these images have to do with refraining from being an intellectual? They were just there, and we were not to think about them–or about anything. Thoughts had to be at a bare minimum. This was basic hygiene, like washing your face or taking out your mouthpiece every night. My car dropped me off at my place of work, a completely nondescript high-rise office building, among an array of hundreds. Through work, five billion people were kept out of trouble, and society was well-ordered. No one must go without work. What did we produce? I wasn’t supposed to ask that

question. The car, as it always did, went toward the parking garage, where it would stay until seven at night, the finish time of my job. I’d heard someone venture that primitives had Sunday off work— absurd! The footboard was ready, and I stepped onto it. It took me through a labyrinth of hallways to an elevator, then through another maze of hallways, to my work cubicle. Then it departed, and work

was to start immediately. I did not understand the purpose of my job. I had a computer console on my desk. The screen displayed newsreels from about two hundred years previous. I was expected to key in comments at the keyboard. Any time I used the word, “Silly,” I earned five points. If I used the word, “stupid” I got seven points. If I ever ventured a comment like, “I don’t understand,” or perhaps, “I would like to know more,” It would be grounds for disciplinary action, and I knew better. I did this work all day, and it was exhausting. Yet, I’d been told repeatedly that I was “doing a good job.”

The AI led government/employer held weekly trainings. During these trainings, I’d been forewarned not to try to figure out the purpose of anything. One caution, among thousands: Do not be a Thinker!

I began work. I felt as though someone was watching me. I looked to my right and spotted Harold, a coworker, sitting in his cubicle. He turned away just as I looked. I assumed I was imagining that he’d looked in my direction. I berated myself for imagining something–I was to focus on work.

I opened my desk drawer because I wanted a finger-numbing device. (My fingers would periodically get sore from a lot of keyboarding.) I gasped. There was a book in the drawer! Terrified, I immediately closed it. I believed everyone in the shared office, about thirty people in the room, heard me slam it shut.

The buzz of chitchat ceased, and I heard someone deliberately cough–probably Mr. Humulin. He was unofficially in charge of office gossip. (Somegossip was tolerated; it was an extra means of reinforcing conformity. And it was a release.)

I concealed the book and had brought it to my dwelling. My home was a studio apartment that I kept fastidiously clean, with appropriate pictures on the walls of troops, government monuments, missiles, and the Esteemed Leader.

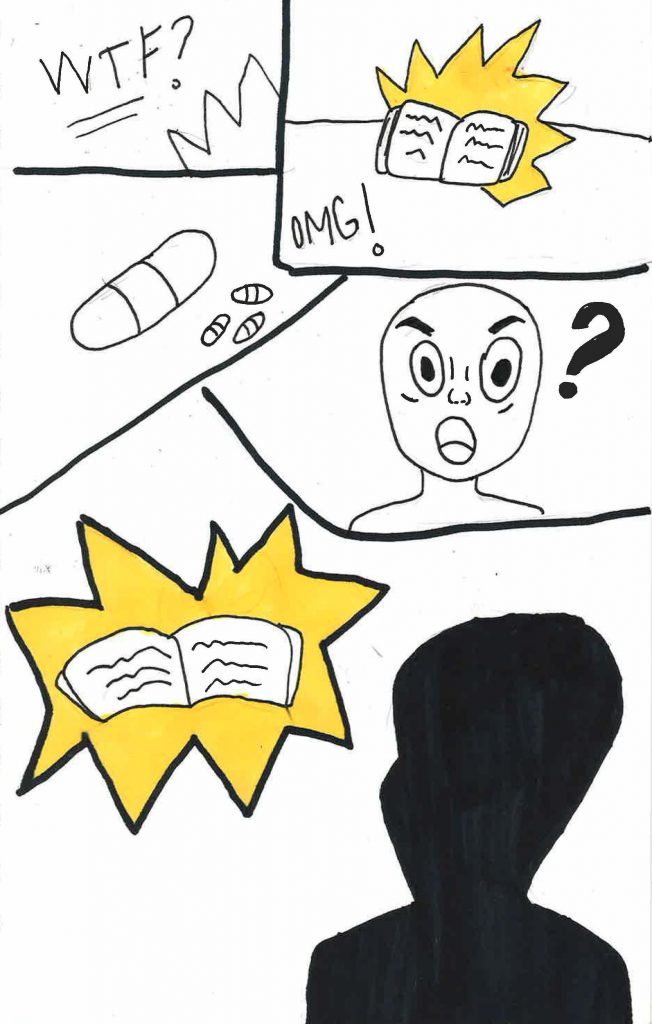

I had the book on my dining room table. I was terrified of it. The title, “How to Develop Your Thinking Ability,” struck me as scary. It was overtly thoughtful–and it was illegal. The book was ancient. I thought if I tried to open it, the pages would fall out or might even crumble. It occurred to me that it was odd that I knew enough even to have that thought.

An unseen force was pulling me toward the book; I fought it off, I retreated to the other end of my dwelling, and I stood next to the bathroom.

From my pocket pillbox, I retrieved a pill. I’d never had to do this.

Crisis pills were to be ingested to shut down the mind–in situations that posed extreme danger to our orderliness. If we had a strong impulse to understand everything, we were to take a crisis pill and shut that down; it was the loyal thing to do. A sensor in the pill container would detect it–the government would know. I could be in legal jeopardy. The surveillance system in my home could activate if I took it.

Yet, I had to do what was right. It wasn’t my fault that some villain had forced a book on me. I told myself it was normal for me to be thoughtless (thoughtless is good) and to make a vain attempt at concealing and bringing home the book. It was stupid. Stupid is good.

I took the pill, but it wasn’t enough. The force put out by the book, the evil force, was stronger. It was involuntary: I sat down in the chair at my table and I reached for the book…

Jack Bragen currently lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.