By Kate Wolffe

Douglas Freitag, known by his friends as Double Digging Doug, has been sprucing up gardens around Berkeley since he attended Berkeley High in the ‘60’s—a member of the Class of 1970, he was mowing lawns back then.

The impulse to tidy and groom a space still drives him: since he became homeless in the spring of last year, he has used his miniature orange broom and dustpan to keep his quarters neat whenever possible. I met Douglas on the corner of Shattuck and Allston in Berkeley while he was sweeping cigarette butts from the sidewalk. He tells me that occasionally he’ll fill a whole day with sweeping the streets—tackling big ones like Shattuck—just for something to do.

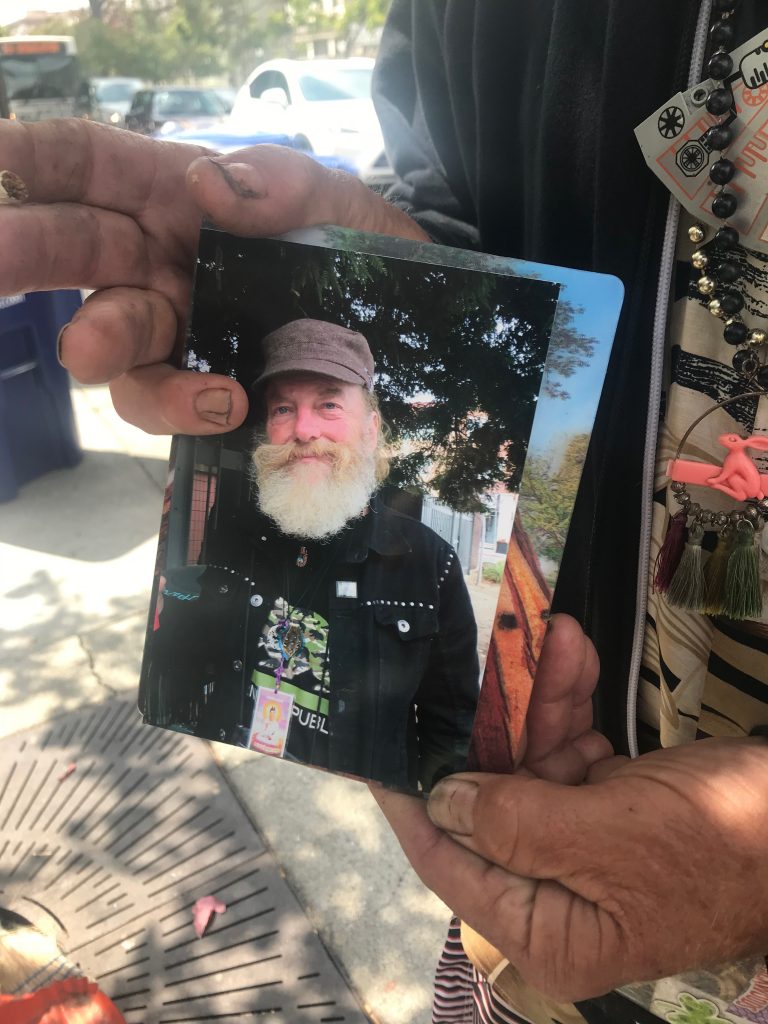

He’s easy to spot with his self-described ‘eclectic style’. When I meet him, he’s sporting a Hawaiian shirt with a black zippered hoodie over it, board shorts, blue and green argyle socks tucked into black leather shoes. Layered over his sweatshirt are four necklaces that feature a unique cast of characters on long chains: a jade Buddha, a Star Wars LEGO piece, and a tiny pink cat. When I compliment his style, he tells me the names of three stores close by where I can find the ‘trippy threads’ he favors.

These streets are familiar to Doug. Growing up he lived further north, on Spruce Street, in a townhouse on Professor Row, where his dad was a renowned professor of entomology and parasitology at UC Berkeley. Proudly, Doug tells me of the way his father helped ameliorate the sugar beet blight, and helped save the sugar economy. His tells me his dad’s influence may have had a role in cultivating his green thumb.

Of teenagedom, Doug can remember specific details: running out to see George Harrison when he visited Berkeley; dancing in the streets to Mo-town; and being treated to a drink at the tiki bar Trader Vic’s down in Emeryville on his 21st birthday. But it’s not just specifics of his own life: Doug knows Berkeley history too. In fact, he holds a veritable treasure trove of it. Doug regaled me with Hearst family drama and anecdotes about meeting and working with the ‘crabapple’ Alfred Peet, of Peet’s Coffee.

He remembers all of these details so well due to memory exercises that he started practicing a few years ago, which consist of singing and telling stories. The songs Doug sings are sad: Irish ballads, mostly. He tells me he feels deep sorrow for the 20 friends he lost in the AIDS epidemic—he counts himself to be one of few who survived. In our short time together he sang me two songs, the Irish sea shanty “All for Me Grog,” and the ballad “Someday Soon,” by Judy Collins.

Losing so many friends to AIDS made Doug prioritize his relationships; so when his friend Dave got sick in 2016 and needed somewhere to go, Doug offered up his home. Although it was lovely to live with his friend, Doug began to find it difficult to resist old vices: “You can’t live with someone who smokes and drinks in a one bedroom and not smoke and drink yourself,” he said.

It’s easy to picture Doug living a different sort of life: a musician on stage at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre singing his sorrowful ballads, or a researcher at the Historical society, sharing pieces of East Bay folklore.

As a young adult, he enrolled in art school to pursue a creative life, but he’s ended up on a different track than expected. Doug lived in a Section 8, rent-controlled apartment on Milvia Street where he paid $221/month for twenty-five years, until his landlord died last spring. In the subsequent shakeout, Doug was left with nowhere to go. He was living in his truck, but his luck turned further south when he had a run in with the police.

In May 2017, weeks after the deaths of his friend Dave and his landlord Alex, Doug ended up in jail for a few days. While there, he worried less about himself than about his truck, parked where it was for so long. Although he says that officials assured him nothing would happen to it, it had been impounded while he was away. When he tried to get it out of the pound, the fees had stacked up so he couldn’t afford to get it back. The truck was everything to him, it had all that he had left in it, clothes, tools, art, memories; he hasn’t recovered since.

“It was a cataclysmic event for me,” he said.

When Doug found himself on the street, it didn’t seem an option to ask his friends, even his siblings, for help. It was his stiff-upper-lip family background—growing up in an Irish Catholic family, Doug learned that if you need something done, you do it yourself. He wouldn’t, rely on anyone to do anything for him.

But it has been tough for Doug to get back on his feet on his own. He has a history of alcoholism, and a few months after being evicted he got a bout of nail fungus, and then a case of lice that has been hard to shake.

However, he’s met friends who support him out here.

He still collects $1,000 from a monthly social security check, but it isn’t always easy for him to collect the money now that he is living on the street without any permanent address. When he lost his truck, he lost his gardening supplies, but he’s been able to piece together his business without them. He tells me he’s been gaining clients, working with another homeless man who lives down the street.

He and his friends subsist on food donations and boxes of $3 to-go fries they get from Burgermeister. Before I left, he tried to hand me a bag of trail mix that had been given to them. I refused, knowing that someone else would be happy with the small bounty. “No, take it, see, none of us have any teeth,” he said, with a cheeky smile.

Street Spirits is a feature in which someone who lives on the street tells us their story.

Kate Wolffe is a reporter and weekend host at KQED.