My Back Pages

by Terry Messman

While attending seminary for four years in the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, I was greatly inspired by people of faith working to overcome the injustice of poverty. I studied the works of Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day, the liberation theology of Gustavo Gutierrez and Leonardo Boff, and Martin Luther King’s call for a Poor People’s Campaign.

I heard the cry of the poor and the call to solidarity with destitute and homeless people. It changed my life forever.

Yet, one simple song — a country spiritual first performed by Hank Williams and later by Joan Baez — may have had a more lasting impact on my life than all the theologians and scholars I studied during my four years in seminary.

The seven seminaries of the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley taught the newly arising forms of liberation theology from all over the world. In El Salvador and Guatemala, Brazil and Argentina, the Philippines and South Africa, people of faith were standing in solidarity with the poorest of the poor and courageously working for political and economic liberation.

When I took Professor Robert McAfee Brown’s course in liberation theology, I saw clearly, with new eyes, that there was an entire unseen world of poverty and oppression all around us — even around the seminaries on Berkeley’s Holy Hill. Yet few activists paid any attention to the poverty and injustice so close to home.

The Long Loneliness

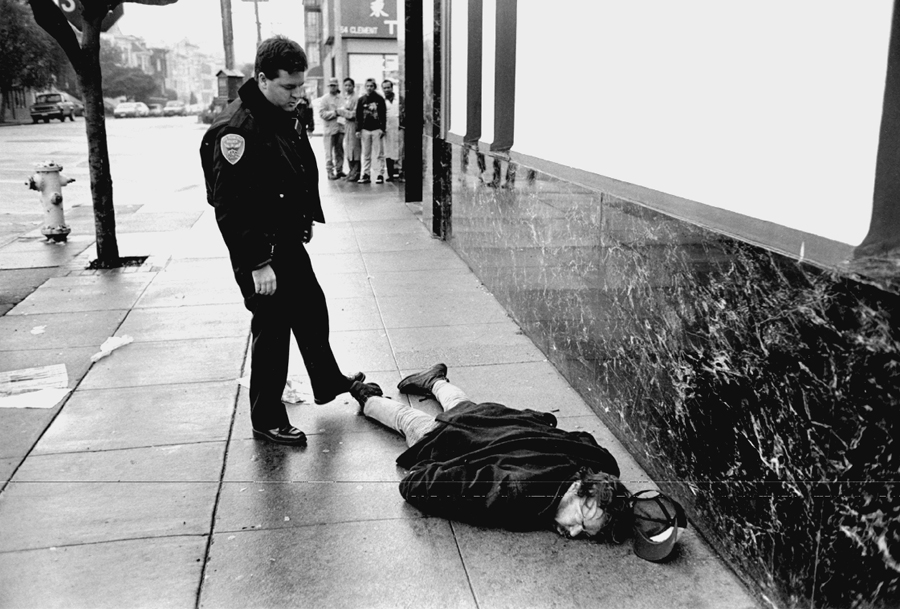

On the streets all around us, multitudes were suffering from hunger, illness and homelessness — suffering, too, from profound loneliness and isolation, abandoned by a society that treated poor people as outcasts and pariahs. The long loneliness.

Several times, while I was working in the Graduate Theological Union library, well-dressed graduate students would sneer in distaste at the presence of homeless people and demand that they be removed from the library as a blight and nuisance. I realized that nothing less than a Biblical parable was happening right before my eyes — an unsettling reminder of the parable of Lazarus who begged in vain for food at the rich man’s gate (Luke 16: 19-31).

In my first year at seminary, I read The Long Loneliness, Dorothy Day’s memoir of founding the Catholic Worker in response to hunger and injustice. That summer, shortly after Darla Rucker and I were arrested in the massive anti-nuclear demonstration in June 1982 at Livermore Laboratory, we traveled to Los Angeles to volunteer at the L.A. Catholic Worker.

I was staggered when I saw the vast scale of hunger, poverty and human misery on Skid Row. For several decades, the Los Angeles Catholic Worker had provided meals, health care and shelter for an enormous number of desperately poor people.

Soon after we arrived, the community celebrated the birthday of one of the Catholic Workers by bringing out a cake with a frosting inscription: “If you want peace, work for justice.” That has now become a timeworn slogan, but I was haunted by that simple phrase.

Members of the Catholic Worker often were arrested for acts of nonviolent resistance to war and nuclear weapons. Yet, they spent 90 percent of their working hours providing meals, clothing and health care to poor people. That was a deep challenge to my own values and priorities.

Every day, they served meals to hundreds of destitute people at their kitchen on Skid Row. And every day, they sang.

Singing in a Strange Land

Their singing raised the question from Psalm 137: “How can we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” Skid Row truly was a strange land where thousands were locked in captivity by merciless, grinding poverty.

Yet, the Catholic Workers sang. I never got over that — the songs they sang in the midst of terrible hardships.

One song I learned that summer changed my life for good. “The Tramp on the Street” is a song written by Grady and Hazel Cole, sung by the legendary Hank Williams and later by Joan Baez.

The song is based on a parable by Jesus about a poor man who asks for food at the rich man’s gate — the same parable that had come to mind when affluent graduate students had complained about homeless people at the gates of the seminary.

The song made an everlasting impression. I was stunned by its power. For years, I was unable to get the song out of my head, and I still need to hear it to this day. The lyrics floored me the first time I heard it.

“Only a tramp was Lazarus who begged,

He who laid down by the rich man’s gate.

He begged for crumbs from the rich man to eat.

But they left him to die like a tramp on the street.”

It was devastating to hear that song on Skid Row. The lyrics exploded inside like a depth charge, exposing the way the richest nation on earth had abandoned millions of homeless people, and by refusing to take action to alleviate their poverty, had left them to die “like a tramp on the street.”

Yet, if the first verse was revelatory, the next verse was heartbreaking. It brings out the full dimension of the tragedy that takes place every time a life is lost on the street.

At first glance, the lyrics may sound sentimental. They are not. Every parent knows they tell the truth with uncompromising emotional honesty. Every parent feels the same tenderness and protectiveness towards his or her child, and the song beautifully expresses the depth of a mother’s love.

“He was some mother’s darling, He was some mother’s son.

Once he was fair, once he was young.

His mother rocked him, her little darling to sleep.

But they left him to die like a tramp on the street.”

The song was a revelation. Every single person on the street was once some mother’s darling son or precious daughter. No matter what the cruel years on the streets may have done, he was once fair and young, and he was loved beyond the telling.

The mother in this song cannot see into the future, when the darling son she is rocking will end up a homeless man, shunned in life and abandoned to an early death. The song’s stinging impact derives precisely from its double vision. It sees a mother tenderly caring for her child, and at the same time, it sees into the future with piercing clarity, and knows that her child’s life will end in tragedy.

Defaced and Disfigured

This man, once so fair and so young, will be defaced and disfigured by the hardships of life on the street. A person made in the image of God will be desecrated. And a society will refuse to care.

The song somehow ended all those useless and unfair questions about who is to be classified as the “worthy poor” or the “undeserving poor.” Those are not the right questions, and they never were. The only question is: What is our human response when some mother’s son or daughter ends up dying on the street?

Songwriters Grady and Hazel Cole still have one more insight to share, the exact same insight I had discovered in the works of Gustavo Gutierrez, Jose Miguez Bonino, Leonardo Boff, Adolfo Perez Esquivel and the other liberation theologians I was studying.

Once, long ago, another child was greatly loved by his parents, only to die like a tramp on the street. With unflinching honesty, this song describes how a parent’s love turned into bitter tragedy.

“They pierced his sides, his hands and his feet.

And they left him to die like a tramp on the street.”

The song describes the execution of Jesus at the hands of the Roman Empire in terms that link his death to the deaths of every mother’s child on the streets of modern America. In truth, it is the same death. “As you do it to the least of these…”

“Mary she rocked him, her little darling to sleep,

but they left him to die like a tramp on the street.”

The song has alternate endings, depending on the singer. Joan Baez, a pre-eminent voice of the peace movement, sings in sorrow for the poor man’s son killed in battle while an unthinking nation glories in its triumph. It is one of Baez’s finest moments.

“Red, white and blue, and victory sweet,

But they left him to die like a tramp on the street.”

The original ending as sung by Hank Williams is a disquieting warning that some people have rejected angels unaware. Jesus was homeless too, so who is that Stranger we turn away from our door?

“If Jesus should come and knock on your door,

For a place to lie down or bread from your store,

Would you welcome him in or turn him away?”

This same insight into the nature of human solidarity has deeply affected the thinking of liberation theologians in Latin America. We are all one body. Those who are crushed or crucified by poverty are part of the Body of Christ, and their lives are no less sacred than the man who died a criminal’s death 2,000 years ago.

Tom Joad’s ‘One Big Soul’

Woody Guthrie perfectly captured the secular equivalent of this vision of solidarity in “Tom Joad,” a song inspired by John Steinbeck’s novel, The Grapes of Wrath, about the struggles of Dust Bowl refugees.

In Guthrie’s magnificent song, Tom Joad and Preacher Casey come to see that all people share “one big soul.” They realize that they are inseparably linked to all the poor and hungry children, and to all the people fighting for their rights.

As Tom Joad flees the deputies and the law, this is how he describes his vision of “one big soul” to his mother.

“Everybody might be just one big soul

Well it looks that’a way to me.

Everywhere you look in the day or night,

That’s where I’m gonna be, Ma.

Wherever little children are hungry and cry

Wherever people ain’t free,

Wherever men are fighting for their rights

That’s where I’m gonna be, Ma.

That’s where I’m gonna be.”

That summer when I first heard “The Tramp on the Street,” I had been listening to Country Joe McDonald’s beautiful rendition of “Tom Joad” on his masterpiece album, “Thinking of Woody Guthrie.” Both songs felt like chapters in the same saga of parents and children torn apart by poverty and hunger on the streets of America.

Both songs expressed the same revelation about the human condition: Life is sacred and it is not just some economic statistic when someone hungers and suffers and dies on the streets of our nation.

It is some mother’s son, some mother’s daughter. It is a human being made in the image of God. It is a desecration of the sacred when that life is torn down.