by Carol Denney

The earliest descriptions of pepper spray and tasers as useful police tools implied, erroneously, that they would safely and immediately render suspects docile and compliant.

When subsequent studies proved that both pepper spray and tasers not only did not produce uniform effects on people, but were lethal for an unidentifiable ratio of the public, the search for a compliance tool by weapons manufacturers interested in the lucrative police market went on.

On Tuesday, July 25, 2017, around 3:00 p.m. in the afternoon, a group of us working at Expressions Art Gallery in Berkeley suddenly heard very loud screaming. We walked outside to the northeast corner of Ashby and Shattuck near the bank, and saw several police officers surrounding and forcing a blond, white man face down on the sidewalk.

As he screamed, already handcuffed, the officers bound him in some kind of leg restraints, and then forced him into a kind of white hood which they put over his head. He kept screaming while they completely bound him in restraints in full view of the public, which took a lot of struggle and time. He kept asking for help.

We don’t know what took place before the screaming. But it had been a very peaceful, sunny afternoon at the Gallery and on the part of Ashby where we were working. We checked with the bank on the corner after at least four police cars and five or six police officers took the man away, and found that there had been no disturbance there.

We were all very shaken up. The Expressions Gallery director and I watched along with several bystanders. We saw two badges, an Officer Rodriquez and an Officer Martinez, but didn’t get any additional badge names or the name of the victim. All of us felt the restraints were making the situation much worse for everyone.

After the man was picked up and put in the police car, the officers laughed together, and one of them, an Asian officer, excitedly claimed that the man had “tried to bite” him, which was not apparent to any of us. It was chilling that they seemed to have no awareness of how frightening the application of restraints was for the man they had forced to the sidewalk, as well as for all of us who were watching.

We don’t know who he was, or if the man who was restrained needed any witnesses. It was all we could think to do to watch in horror. The officers claimed they could not tell us what had happened, and while there might be privacy constraints, it seemed absurd that no information whatsoever was offered in the light of the use of the strange hood and the restraints.

There seemed to be no awareness among the officers of the severe personal humiliation for the man in restraints, and the horror for us as bystanders left to wonder, as the police cars sped away, what in the world would warrant such treatment. It is frightening to think that if one cries out in anguish or fear as one is arrested, this restraint system might become routine.

We had trouble the rest of the day getting the incident out of our minds. We can’t imagine that this is necessary. The Expressions Gallery is the loveliest place to wander through, full of ideas, excitement, and color. The gallery has poetry readings, classes for adults, events for children, and art openings with live music and a feeling of lively neighborhood and professional exchange. That afternoon it was robbed of its unique sense of peace and exploration, and none of us can understand why.

There is currently no policy in Berkeley governing the use of what is apparently called a “spit hood” and the accompanying restraints, unless the following wording is clear to you:

General Order H-06. #2 states: “It shall be the policy of this Department to handcuff or otherwise effectively restrain all arrested persons (excluding infraction citations where no transport is necessary), or detainees as reasonably necessary, to protect the lives and safety of officers, the public, and the person arrested.”

The General Order continues with #3:

“Use of a full or partial body restraint systems (e.g., the WRAP, ankle restraint systems, ambulance gurney with five-point straps, etc.) (i) While initial use of handcuffs behind the back and hands-on control techniques may be necessary for officer safety, if circumstances dictate greater care should be taken during transportation, supplemental restraint devices and/or alternative transportation options should be considered. (b) In deciding whether restraint of a person’s hands behind his/her back will aggravate a physical disability, injury, or obvious state of pregnancy, the officer should consider the totality of circumstances, including: (1) Observable signs of disability (e.g., partial paralysis, convulsive seizure activity, medic alert ID, disabled person placard, etc.); (2) Statements of the person or others regarding the person’s condition; and, (3) Indications the person is at significant risk of positional asphyxiation (ref. Training Bulletin #234).”

A spokesperson from Safe Restraints, the manufacturer, described the system as “very comfortable” and “magical” in terms of its utility in quickly and safely restraining combative, threatening individuals, adding that the system was designed “only for situations where there is a danger to the suspect, to individuals, or to officers.” The WRAP restraint was first deployed in 1996, and has been used by Berkeley police for about ten years.

The origin of this restraint system, according to writer Maddy Simpson of the science-based website Modern Notion, is in the psychiatric wards of mental hospitals in the form of “wet sheet packs.” Simpson states, “The Wrap, a design by a company called Safe Restraints Inc., has a few separate pieces that clip together to hold the prisoner. An ankle wrap keeps the prisoner from kicking, a blanket-like leg wrap tightens around the prisoners legs and a chest harness tightens around their chest. After all the parts are properly put on, the chest harness is attached with a chain to a piece on the legs, locking the captive in the sitting position.”

Simpson’s article continues, “Originally a branch of hydrotherapy, wet sheet packs were sheets dipped in varying temperatures of water and wrapped around the patient tightly. The thought behind the treatment was to exclude all air from the inside of the pack, so that a patient’s body would sweat out colds. The therapy also aided in the treatment of rheumatism. But, the wet packs were being used as mechanical restraints just as commonly as they were used for therapy. The wet pack was so commonly used as restraint that in 1873, they were defined no longer as a therapy, but as a form of restraint, and lost popularity thereafter.”

Safe Restraints, Inc. makes the same claim originally used about pepper spray and tasers, that the WRAP is easy to apply, safe to use, and creates immediate compliance. But that isn’t what those of us watching on Ashby Avenue saw on July 25. We saw a prolonged, exhausting struggle for all parties, humiliating and debilitating treatment of a captive as yet not convicted of any crime.

Whether or not this exotic restraint system is necessary is, according to the Berkeley Police Department’s current guidelines, a matter determined by ambiguous decisions of the officer or officers at the scene using words like “reasonably necessary” and determinations of positional asphyxiation which most physicians agree cannot be determined solely by observable physical features. There appears to be no mention of the hoods, or any set of restrictions for their application.

The additional effect for those of us who are workers, neighbors, and passers-by, and who simply observed the imposition of police restraint, was chilling. We have no idea what in the world would constitute appropriate use of a restraint system which requires a fifteen minute physical struggle by at least four officers who seemed to regard the application of the WRAP restrain in and of itself a significant victory when they were done.

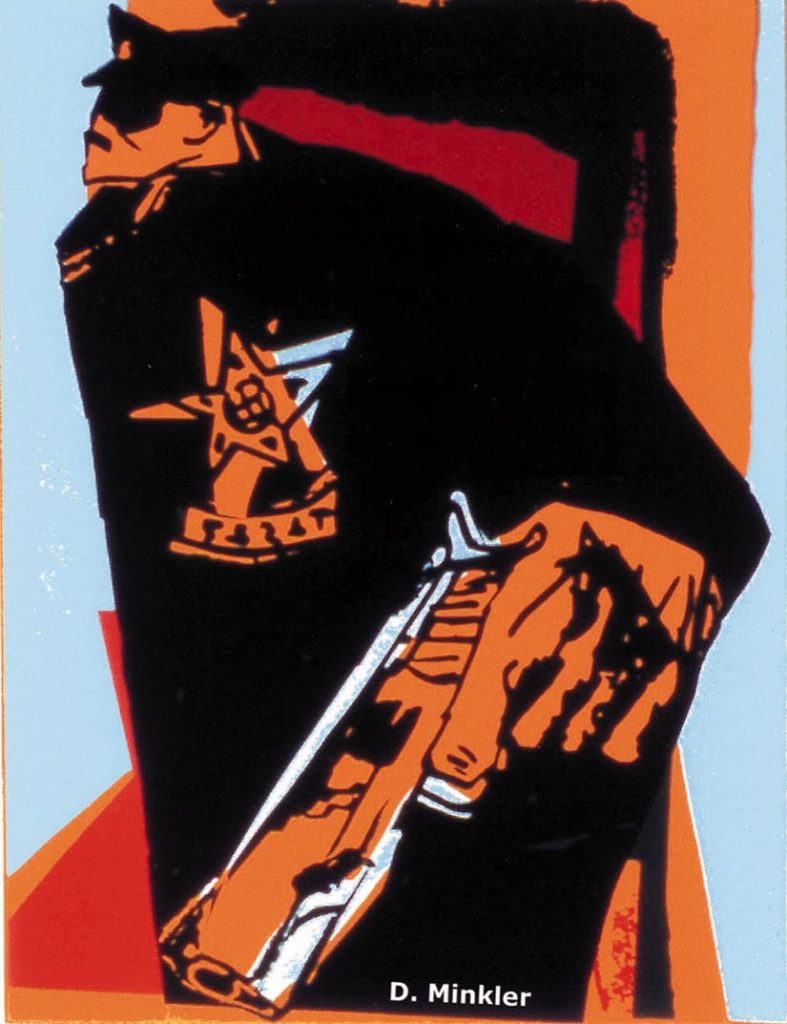

The application of the hood rendered the captive completely anonymous, a hooded figure such as one might see in photographs of Guantanamo.

According to Simpson, “The company’s website boasts ‘no deaths or injuries in 19 years of use,’ but in 2005, a similar device caused a man to asphyxiate and die even with paramedics on the scene. Risks from the wrap are due to the over-tightening of the pieces, causing breathing distress.”

Simpson refers to the use of WRAP restraints as “an ethical dilemma both in the law enforcement and medical worlds.” Berkeley citizens and others whose police departments have adopted this restraint method need to note that this frightening, debilitating, and humiliating technique deadens not just police officers but onlookers as well to the inhumanity of approaching often confused, frightened people with the concept that any noncompliant behavior may qualify a person suspected of a crime to being tripped to the sidewalk and wrapped completely in restraints which can inhibit breathing.

The use of this technique was not debated at the Berkeley City Council, or put before voters. It was eased into use on the same false premise as pepper spray and the taser, which found ready welcome in many police departments before their potential lethality was finally admitted by manufacturers.

Police departments interested in using WRAP restraints, or the next new compliance tool rolling out of manufacturers’ warehouses, should be required to publicly discuss their use and utility to the people they serve. It seemed clear to those of us standing on Ashby Avenue observing the use of a WRAP restraint, that little could justify such treatment, and worse, that the police seemed to think no justification was required.

A police department with a proven history of racially discriminatory stops, such as the Berkeley police, should never be allowed to use controversial new and sometimes lethal techniques without much more clarity about how, and upon whom, they can be used.

It is easy for the Police Department to use manufacturers’ claims about effectiveness and safety until the medical communities’ reports, coroners’ statistics, and lawsuits catch up. But especially a city with the Police Review Commission, such as Berkeley, needs some way to make sure the community served by its police force is being consulted about how it is being policed before having to witness another human being br