by Erin McCormick

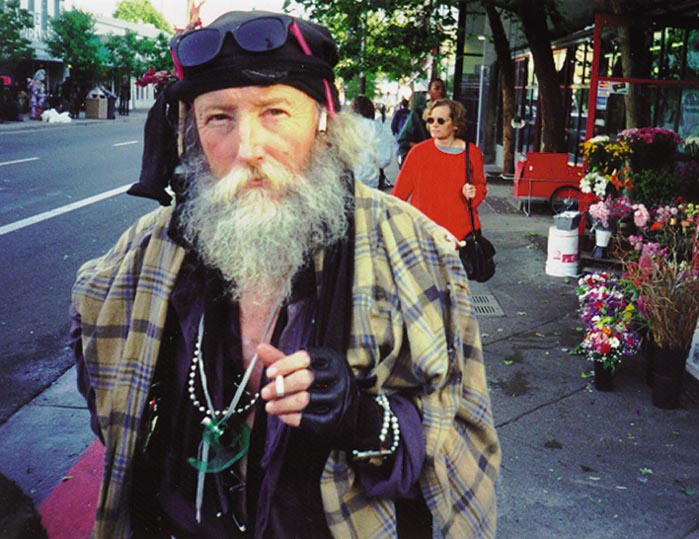

He brought his own brand of hate to a city renowned for its 60s-style peace and love. Berkeley’s “Hate Man,” as he was known, lived on the streets, often standing on street corners yelling “I hate you” to passersby — a sort of counter to America’s counterculture icons.

“He called it oppositionality,” said Dan McMullan, a close friend. “His philosophy was that if you were honest about your negative feelings, everything else would just fall into place.”

The Hate Man was also known as Mark Hawthorne, before he rose (in his opinion) from a job as a reporter at the New York Times for nine years, from 1961 to 1970, and began living as a homeless person in Berkeley. His life story, and his death on Sunday, April 2, at age 80, illustrates a fact not unfamiliar to those trying to help the homeless: some people do choose to live on the streets.

Hawthorne’s sister, Prudence, reached by phone in Montana, said she visited him two or three times a year and admired his every move. “We like to say he lived the way he wanted to live,” she said, “and that’s a rare thing.”

Hawthorne served as an intelligence officer for the Air Force in the 1960s, she said, and remembers him dashing out of a movie theatre when he was called to duty during the Cuban missile crisis. Their father worked as a reporter for the Associated Press and her brother Mark followed in his footsteps, working as a metro reporter for the New York Times.

But, she said, he found that he had no time to himself and “decided to change his lifestyle.”

He quit the Times, she said, but shortly after was hit by a car in New York City, spending most of a year in and out of the hospital with a shattered hip. After that, in 1973, he relocated to California.

Numerous newspapers have profiled the Hate Man, who said he spread hate as a way of establishing real communications with people. One year, according to McMullan, a Japanese film crew showed up in Berkeley to do a documentary on him: “Then, once they made the movie, they took him to Japan and he got to tour all around.”

Mark Hawthorne’s nephew, Jesse Hawthorne Ficks, said his uncle served as almost a social worker to those on the streets. “We all know that there is a thin line between love and hate,” he said. “Saying ‘I hate you’ is saying ‘I love you.’”

“I don’t think the Hate Man is trying to counter the culture of peace and love,” he said. “He’s trying to go further — to help the people who fell through the cracks.”

Hawthorne usually resided in his own “Hate Camp” inside People’s Park, which was created by radical activists in the 1960s on a piece of land near UC Berkeley.

When Hawthorne’s health began failing this year, he made it clear he did not want to live anywhere other than People’s Park, despite record rainstorms in the area.

“He did not want to live indoors,” said Rev. Marianna Sempari, an interfaith chaplain for Berkeley Food and Housing, who watched his health decline. “Our role is about respecting someone’s agenda. It’s not our role to say that people need this, this or this.”

In February, Ficks picked his uncle up from the hospital after some heart problems and he knew he had no choice but to take him back to People’s Park. “He was determined to live this way,” Ficks said. “Getting him back there was like his last wish.”

Then one night during a ferocious storm, McMullan, who heads the Berkeley Disabled People Outside Project, got a call from a friend who said the Hate Man wasn’t looking too good. He went to People’s Park and found Hawthorne in the bathroom, soaking wet, trying to dry himself with the hand dryer.

“He looked dazed and he was turning blue. We got him to the hospital.” He died in a nursing home several weeks later.

Despite first impressions, the Hate Man had come to be known as a source of comfort to some of the more vulnerable homeless people living in People’s Park. Friends said he handed out advice and cigarettes to anyone who would give him a ceremonial push.

They quoted him as saying: “Maybe I’m a lot like Jesus. But I give out cigarettes instead of miracles.”

During the late 1990s, Hawthorne organized daily drumming circles on UC Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza, in which participants banged buckets, pans and sticks to make a lot of noise.

“It was about getting anger and negative toxins out in the open,” said Alex Thorson, a longtime friend who works as a homeless outreach coordinator for Berkeley Food and Housing. “There was a lot of irony and satire in what he said. When you unraveled it, it was really kindness and compassion.”