by Lydia Gans

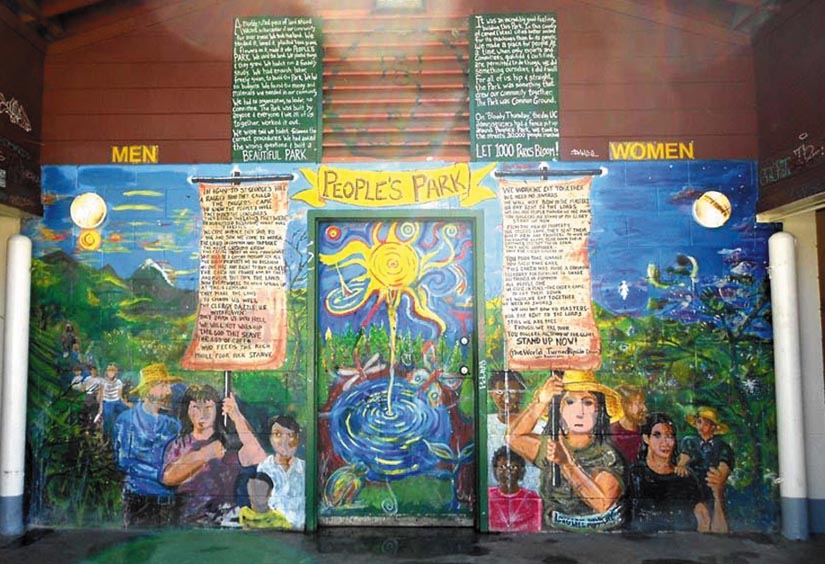

On April 23, friends and neighbors of People’s Park will celebrate its 48th birthday. People’s Park, a 2.8-acre green space south of the University of California campus in Berkeley, was created in 1969 after massive protests to preserve the land as a park for the people of the community.

For nearly a half-century, the community has continued to maintain the park in spite of periodic confrontations with the University of California. The latest threat to the park — the announcement that UC officials are considering building student housing on the land — will not go unchallenged.

On March 11, the latest challenge to People’s Park landed on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle. Carol Christ, UC interim vice chancellor and provost on a committee to produce needed student housing, described People’s Park in a landowner’s overly possessive terms.

“We own the land, but we’re essentially running a daytime homeless shelter in the park,” Christ said.

There’s no question that housing is needed in Berkeley, but so is open space, accessible places where people can sit peacefully and enjoy the fresh air or socialize with others in their neighborhood. That’s why we have dozens of parks all over Berkeley in different neighborhoods, reflecting the various interests or needs of the people in the community.

People’s Park serves a very diverse community. On a good day, there are groups of people in conversation, or gathered for a Food Not Bombs vegetarian meal or a Catholic Worker Sunday breakfast. There may be a basketball game going on, or someone tossing a ball to a dog on the lawn or practicing gymnastics.

Some park users play chess or board games while others are quietly reading, listening to music or checking their electronic devices. There are young people and others who are frail and elderly. There is a core of people who have been active in the park since its inception. But whether they are housed or homeless, they are not in the park looking for a “daytime shelter,” as Christ claimed.

The park has a history worth recalling. In 1968, the University of California used eminent domain to evict the residents and demolish all the houses on the block. The demolition was seen by many as UC’s attempt to suppress the flourishing and rebellious counterculture on the southside. There was talk about building student housing, but nothing happened.

For a year the empty lot was an eyesore, muddy and strewn with garbage. In April 1969, activists put out a call for people to help create a park. Hundreds came and cleared the ground, planted flowers and trees, and built a children’s playground. They created a park — a People’s Park — that still lives today.

U.C. officials met briefly with park supporters, promising to communicate with them before acting, but it was an empty promise. Thursday, May 15, 1969, was marked by a violent police raid and became known as Bloody Thursday.

Early in the morning, hundreds of armed police took over the park and erected a fence around it. Thousands of people rallied and marched to the UC campus, as police fired tear gas into the crowds, and huge demonstrations continued through the day until sheriffs began firing shotguns at the demonstrators.

A young man named James Rector was killed, another person was permanently blinded, and many were seriously injured by the police. The National Guard, ordered into the city by then-Governor Ronald Reagan, occupied Berkeley for days, breaking up gatherings and arresting protesters. A military helicopter hovered over a crowd and sprayed toxic gas, sickening and temporarily blinding people. The horror went on for more than two weeks and finally culminated in a protest march by about 30,000 people.

For three years the fence remained around the park. Then, one day, the people tore it down and the park came to life. A community of gardeners formed, planting trees and flowers and creating a vegetable garden along the western end, welcoming everyone to help themselves to the produce. The garden is productive to this day, in spite of continued harassment by the park’s management. This writer is enjoying the delicious collard greens growing there right now.

The gardeners built a shed to store their tools — until it was taken away. Continued requests for a composting bin in the park are still being ignored, in spite of the quantities of food waste left from the daily meals that are consumed there, all of which now goes to the landfill.

There have been periods when the water was turned off. Park activists have been thwarted in other attempts to improve the park. To deal with unsightly piles of clothing and material left near the entrance, they built a freebox. The University removed the freebox. The activists built a new freebox. It went on that way for years — each new freebox was more solid than the last, and each was promptly removed by order of UC officials.

The last one, made of concrete and constructed with an elaborate and amusing ceremony, was gone by morning. At that point the park activists gave up.

It was the University of California’s decision in 1991 to put volleyball courts in the park that drew considerable attention from the community and is still referred to scornfully. With no advance notice, workers appeared one day under police protection, put up a fence and set up volleyball courts in the center of the park. Hardly anybody played volleyball.

Six months later, the volleyball court came down. As people gathered, someone appeared with a chainsaw and cut down the post that held the net. The wood was retrieved, cut up and used in making a picnic table and benches.

Over the years, the Park has been subjected to poor maintenance by UC, particularly the bathrooms, as well as the stage and other structures in the park. It would be hard to find another neighborhood park that is so poorly maintained.

The university promises to provide housing and services for people in need, but there is little reason to believe they will keep their promises. This is a good time to reflect carefully on what happened nearly 50 years ago — and make sure that it doesn’t happen again.