by Carol Denney

The most compelling voices in the studio of Youth Spirit Artworks (YSA) can communicate without making a single sound. They roar out of the canvases and the artwork on the studio walls in powerful shapes and colors. They’ve transformed ordinary objects such as wooden chairs and tote bags into vibrating declarations of self-expression.

The “Visions of Equality” project’s painted wooden doors are powerfully expressive of the individuals behind the paintbrushes, with bold colors and the courage it takes to work large across a space without the opportunity one has to hide in a journal or a sketchbook.

It’s all there, a spirit of self-determination and purposeful exploration of color, shapes, patterns, and symbols both personal and universal.

Artist Dre’an Cox’s painted door is playful, reflecting a Pokémon theme from video games.

Gina Wardlaw’s door is a portrait of a strong, regal woman in bright colors looking calmly at the viewer.

Other doors also take the widest view of the theme, almost entirely lining the fences of the spacious, bright backyard area of the YSA studio like bright boat sails in a harbor heading for new worlds.

Youth Spirit Artworks Art Director Victor Mavedzenge’s painted door stands among them, testimony to his own deep talent and his MFA Degree from The Slade School of Fine Art in London.

YSA staff members Danielle Gibbins, the program director and youth advocate, and Lia Li, a student from China who is assisting with the entrepreneurship project, remind visitors that the studio’s work, with its inviting array of clean paintbrushes and working tables, is guided by the youth themselves.

“We want to reverse the top-down model,” says Gibbins. “If they want to do more products, more T-shirts, it comes out of their discussions every Friday.”

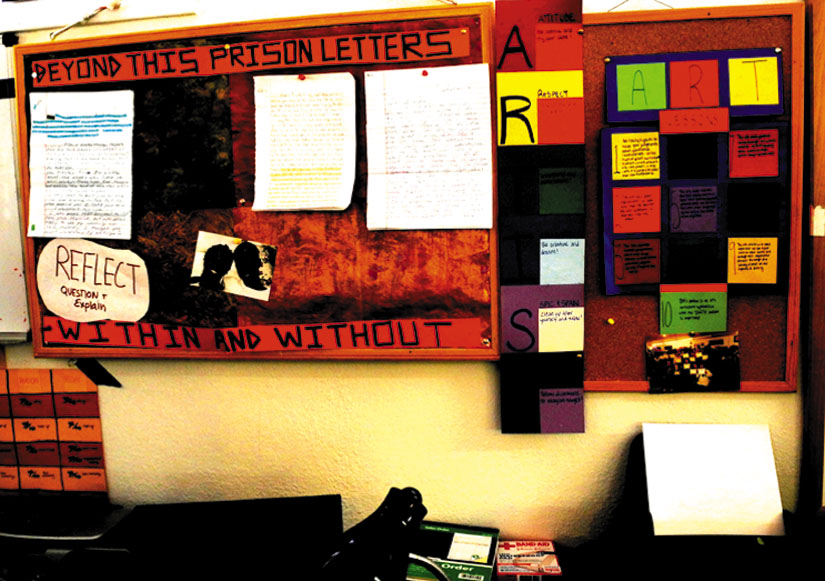

The young participants, who range from 16 to 25 years of age, check in together every week to make decisions about their projects, ranging from fine arts, spoken word, and writing projects such as the “Beyond This Prison” letter-writing project which began as correspondence between Louisiana inmate Glen Robinson and Berkeley resident J. R. Furst. The young artists also pursue the opportunities and challenges of larger community art projects, entrepreneurship opportunities, and product sales.

The youth can earn money directly through their sales of artistic products, as well as by applying for progressively focused work opportunities using a variety of skills, such as keeping track of sales data, assisting with communication and media, and project management, earning more as they shoulder more responsibility.

The money they earn is theirs. They’ve seen what can happen with a particularly popular T-shirt: people walk in off the street requesting it, it flies off the shelves, and YSA can run out of stock entirely.

“It helps them become more independent and learn to budget,” explains Gibbins. “They have the freedom to do what they want.”

YSA’s mission is to use art jobs and jobs training to transform the lives of low-income and homeless youth to ensure that they meet their full potential, which often has more to do with self-confidence and emotional clarity than the art itself.

Many of the participants don’t come into the program thinking of themselves as artists at all. When they leave the program, they often have a very different view of themselves and their talents, whether they see themselves as artists or not.

“They discover that with hard work they can do anything,” states Gibbins simply, as Li nods in agreement. “They learn to ask for help. Art is just a medium through which they learn.”

The community organizations working in partnership with Youth Spirit Artworks comprise a long list. Participants learn about the program largely through word of mouth in the community. YSA murals and mosaics spring to life throughout the town of Berkeley and young people either see it for themselves or hear about it from friends and teachers at local schools, or groups like YEAH (Youth Engagement, Advocacy and Housing) and BOSS (Building Opportunities for Self Sufficiency).

YSA has a partnership with Urban Adamah, a community garden on San Pablo Avenue where youth can harvest eggs, learn about plants and farming, and see the skills required to organize with others — literally from the ground up.

Respected local artists and poets conduct workshops with the participants, and the youth take field trips that engender discussions they may never have had before about college requirements, job skills, and possibilities for a future some have never had the encouragement to envision for themselves.

There is no template for an original model. In the eight years of YSA’s existence, the best practices of youth empowerment organizations with similar goals have informed the program, but YSA is original as an organization.

It partners with local artists and has a dedicated and deeply educated staff, but it is designed by the youth themselves, who move seamlessly through the studio in ways that convey connection and respect.

“They love to sing,” says Gibbins. “There’s a lot of community organizing,” she adds, and mentions contributions from the Juice Bar Collective that quickly became favorites, even to some of the youth who were initially more used to junk food.

“It’s hard to quantify the value of hope — and resilience,” Gibbins says. The need to measure the youths’ progress has inspired efforts to try some testing, but the point is well taken.

How do you measure what happens to someone who walks through a museum, or who is suddenly given not just the opportunity to paint a chair, but to use their own judgment about the design and the colors?

What happens to a young mind when their personal vision or expression, played across a T-shirt, catches peoples’ fancy and sells like crazy?

Art, poetry, and music have always been the first programs cut in most school budgets, so many young people have no idea what transformative power the arts can have unless they have personal family or friends who can make the introduction.

But YSA’s comprehensive approach to personal transformation is wider than any paintbrush, and more lasting than any song, especially coupled with the serious requirements of budgeting for community projects and creating media for community events.

Its greatest source of support is still personal donations, a supportive board, and community connections through its work, which seems perfectly situated in a South Berkeley neighborhood with an impressive balance of retail stores, arts groups, and cooperatives.

“Art is a piece of it,” says Gibbins, “but there’s so much critical thinking and creativity.”

The grounded nature of YSA’s effort shows in its young participants, such as Jason, who has been involved for three years. He shows his work if requested with quiet confidence and pride, and if complimented on his considerable skill as a draftsman, he simply smiles and says yes, as though there is clarity in his own mind that should he elect to work in the arts arena, he has the required skills.

On a recent Friday afternoon, the corner of Ellis and Alcatraz Avenue in Berkeley came alive with Youth Spirit Artwork leaders, GHA Design representatives, Ecology Center organizers, UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design students, Climate Action Coalition partners and other local groups who collected input from the community about building a “parklet” or “artlot.”

There were drinks and snacks, and large informational signs about the project, and everywhere you looked, there were lots of creative, structural models of different sizes and shapes clustered around the curbs to help get people thinking about possibilities. Small groups chatted, strolled, and brainstormed together in the sun.

Youth Spirit Artworks worked with 144 young people last year alone, an impressive, unmistakable metric which prospective donors can contemplate along with the distinctive visual projects.

These are 144 young people who potentially have a better sense of who they are, a better sense of their worth in the world, improved skills for job interviews, and even a resume.

It might not be the easiest thing to measure. It’s a lot like the rush of possibilities people sense once they’re exiting a great exhibit at a museum or art exhibition. It’s much more than a paintbrush.