Interview by Terry Messman

Street Spirit: You’ve devoted many years of your life to nonviolent resistance to nuclear weapons. When did you first become involved in the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action?

Shelley Douglass: The Pacific Life Community was the original group that started the Trident campaign. The crucial thing about it was that the whistle was blown on the Trident by the man that was designing it, Robert Aldridge. Jim and I had met Bob Aldridge when we were in the middle of the Hickham trial in Honolulu. [Jim Douglass, Jim Albertini and Chuck Julie were on trial for an act of civil disobedience at Hickam Air Force Base in protest of the Vietnam War.]

We didn’t know very much about Bob Aldridge until he came to visit us at our home in Hedley, British Columbia, several years later. He told us a very moving story about how he had spent his life designing nuclear weapons, and he and his whole family had made the decision that he should resign from his job for reasons of conscience. They had taken a tremendous cut in income. They had 10 kids, and his wife had gone back to work, and the whole family was behind this decision.

After he told us this story, Bob wanted to know if we knew where the Trident was going to be home-ported. We had never even heard of the Trident. He told us it was going to be stationed just below the border. We were living in British Columbia then, just north of the U.S. border and the Trident was going to be home-ported in Washington state, just to the south.

He kind of handed it to us. You know, “Do something about this!” [laughing] And we were all burned-out activists from the Vietnam War. We had gone through a lot of antiwar resistance, families had broken up, and we had not been nonviolent to each other. So none of us in our whole little community of friends were very anxious to be active again.

Spirit: Given that history of exhaustion and burn-out, what did it mean for you to take up this struggle?

Douglass: We held a retreat at the Vancouver School of Theology where I was studying, and we decided that we would give it a try, but we would do it by committing ourselves to nonviolence as a way of life. So we would deal with our own sexism, our own economic privilege, our own racism — all the things that we felt had made Trident necessary.

So we decided to make this experiment in nonviolence as a way of life, and the Trident campaign would be the political arm of it. But confronting our own interior Tridents was at least as important as that external political resistance.

The Pacific Life Community was international from the beginning, involving activists from Canada and the U.S., and it very carefully tried to confront issues of sexism and privilege and economic domination as much as learning about Trident.

First Acts of Resistance

Spirit: How did you begin your campaign of nonviolent resistance to Trident?

Douglass: We did all kinds of legal demonstrations around Trident. The first action we did was an Independence Day garden planting in July 1975. A few of us climbed a fence into the Trident base and planted a vegetable garden on the security perimeter road, and got arrested for that.

Spirit: That was one of the very first acts of civil disobedience against Trident?

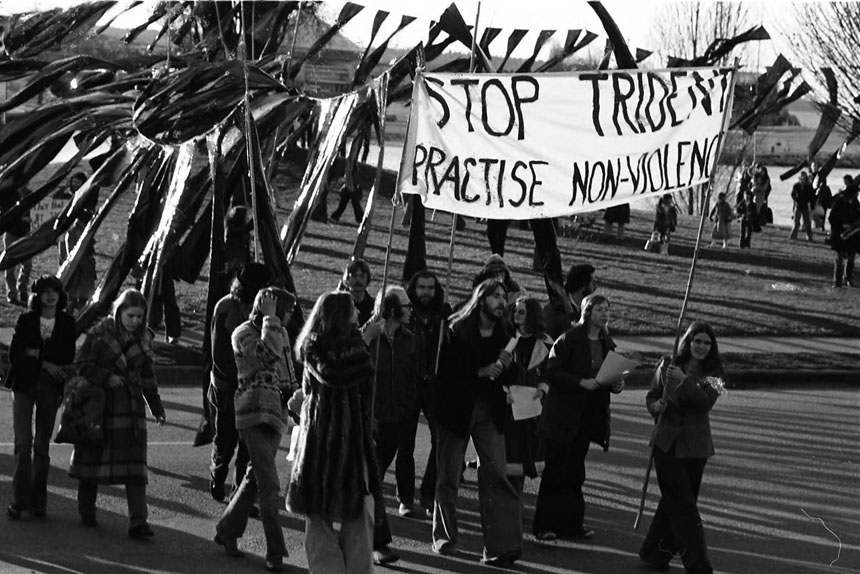

Douglass: Yes, that was a small action. We had a whole series of events in Vancouver on Trident Concern Week in November 1975 where the city officials made a statement about the Trident. We did a lot of public education and we had a parade through the city with the “Trident Monster.” It was this very enormous sculpture thing that people carried through the city. It was as long as the Trident submarine — two football fields long — and a long line of people carried poles with a black flag tied to it for every one of the submarine’s 408 nuclear warheads.

Then in 1976, the “Trident Monster” was brought across the U.S./Canada border and down to the Trident base where we cut the fence and walked the Monster home onto the base. There was a big crowd of people, including a couple hundred people who went through the fence onto the base, including kids who were wanting to be part of it. A bunch of us were arrested and various people went to jail for that action.

Spirit: Did the fact that you cut through the fence at the naval base lead to a longer jail term?

Douglass: Yeah, we went to jail for that one. I was jailed for three months for that action because we had been on the Trident base. We were arrested and put on buses. When you go to jail for something like that, you don’t deny it. Rather, you tell why you did it. I went to jail a bunch of times, but that was my first long time in jail.

Spirit: What was it like for you to spend your first long sentence in jail?

Douglass: It was pretty amazing because we formed a community with the women we were with in the King County Jail. There were almost a dozen of us from the Trident campaign who were there in jail. All of our consciousness-raising things we did in the community spread though the jail because we wound up doing them with the other prisoners, as much as we did them with each other. It was very interesting.

Spirit: What kind of consciousness-raising did you do with people in jail?

Douglass: Well, one of the main things the prisoners liked was weather reports.

Spirit: Weather reports? What kind of weather is there in jail?

Douglass: It’s an old phrase. It means sitting in a circle and telling how you are. We would do that in the morning and the evening, and the other prisoners wanted to take part in it. It became obvious quickly that no one had ever asked them how they were before. We had long sessions of weather reports in the tanks that we were in with all the women, and we built up some community there. It was pretty amazing.

Spirit: The women in jail responded because someone was actually interested in their feelings and experiences?

Douglass: Nobody had ever asked them what they were going through before. So the idea that they could sit down and talk about what was going on in their feelings, and share things without hostility or judgment, was a new thing. I don’t know where they took it, of course, after we all separated, but it was pretty amazing while it was going on.

Images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Spirit: You and two other women from Ground Zero, Mary Grondin and Karol Schulkin, did an action on Ash Wednesday in 1983, when you climbed the fence and walked into the Bangor base.

Douglass: Yeah, we went over the fence right in front of the house where Jim and I lived, which is where the railroad tracks go into the base, and then we walked up the tracks.

Spirit: Didn’t you leave photos of the victims of atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki all along the tracks as you walked into the base?

Douglass: Yes, we had some signs with the pictures on them and we walked up the tracks and prayed. We passed various people. We passed a school bus and all the kids were watching us, but we weren’t stopped until we got quite far into the base. We didn’t reach the weapons storage area; that was a long ways away, but we got fairly far in.

Spirit: After you were arrested, you were sentenced to jail for 60 days. Why was it worth going to jail to walk up those railroad tracks on Ash Wednesday?

Douglass: Well, those were the tracks. All the weapons came into the base on those tracks. The missile motors with the solid fuel propellant which sends the missiles into the air came in on those tracks. So did the White Train with the nuclear weapons. If we had walked all the way to the end of the tracks we would have wound up at the storage area for the nuclear weapons.

Spirit: By leaving photos of the victims of Hiroshima along the tracks, were you warning that this is what happens when the train reaches its destination? The final destination is a holocaust?

Douglass: Right, we were trying to raise consciousness among the people on the base. You know, in one sense they’re well aware of what it was all about; but in another sense, they didn’t want to think about it. So it’s still important to raise awareness about that issue.

Spirit: Were you able to use your trial to raise public awareness about the threat of nuclear weapons?

Douglass: We had a good trial. Mary Kaufman, who was a lawyer and prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crime trials, came as part of our defense. So we had three women defendants and we had Mary Kaufman as one of our witnesses. She was very powerful in talking about what those nuclear weapons could do and why they were against international law. Mary was a very erudite speaker. She was a person who could put all kinds of law into very succinct paragraphs, which was good because she didn’t have much time in court.

Spirit: There is so much historic significance in having a Nuremberg prosecutor testify at your trial. What did she say about nuclear weapons in light of the Nuremberg principles about war crimes?

Douglass: She basically said that these weapons violate international law and that, because of the Nuremberg principles, it’s no longer a defense to say that you are part of the military or that you are just doing your job. She said that international law is more important.

Mary said that the U.S. has signed conventions and treaties saying that we should disarm and that we would not use nuclear weapons first, even though Trident is a first-strike weapon. And those laws are all higher than any national or local law, so if you break a law like a trespass law, which is what we broke, to try and stop the greater evil from happening, you’re justified in doing that.

As a Nuremberg prosecutor, she said she prosecuted people who did things for Nazi Germany that had the same kind of results that the use of a Trident weapon would have. And were there to be such a trial again, she would be prosecuting people from the Trident base for crimes against international law.

The Bomb and the Sacrament

Spirit: Looking back at Ground Zero’s many years of resistance to Trident and nuclear weapons, what were the enduring accomplishments of that campaign?

Douglass: Well, of course, the campaign still goes on, so Ground Zero itself is an enduring accomplishment. I think one of the major things that came out of that campaign is the sense that we’re all one and we’re all in this together.

The campaign was started by the person who designed the Trident missile. We worked always with people on the base who were helping us in sort of surreptitious ways to get our leaflets out or whatever. There were a number of workers who left the base, some of them in very moving ways, because they had decided that they couldn’t do this any longer.

Spirit: What do you mean that some left in very moving ways?

Douglass: There was a guy named Derald Thompson who was not only in the Navy, but was on a Trident submarine. He was a Catholic layman and one of the things he did when they were at sea was he would give the Catholic crew members communion. The communion wafers that were consecrated were kept in the same safe on the submarine as the key that would turn the lock that would fire the missile.

Spirit: Unbelievable. The sacrament of faith kept in the same safe with a key that could incinerate millions. What impact did that have on him?

Douglass: It was a process of years of discussions and prayer and thought on his part. And one day he made the connection that here was the key and here was the Eucharist and he couldn’t do that anymore. He resigned, left the Navy, and took a long time to find another job. It was just very moving to see somebody make that huge step because of realizing the absolute contrast between life and death.

Spirit: The keys to life and the keys to a holocaust that could end all life.

Douglass: Exactly. So, for me, those kinds of things were actually more moving than the civil disobedience, although I love doing civil disobedience.

Spirit: What else was of lasting significance? What was most memorable from your work at the Ground Zero Center?

Douglass: I think the ongoing relationships built with people in the county. Also, the commitment to civil disobedience, and the use of international law as a way of trying to call people to account. Those are all important. The campaign was a Gandhian campaign and still is, so the long commitment to nonviolence and to trying to listen to the other side — those are all really important things.

Spirit: What were the toughest times or the most troubling moments during the Trident campaign?

Douglass: Well, the White Train action when everybody kind of went bananas and went running onto the tracks.

Ground Zero was part of a community called the Agape Community that stretched from Amarillo, Texas, where the bombs are assembled, all along the railroad tracks to Bangor, where the bombs were put in storage. Our community had a very specific way of doing actions, partly because the train was dangerous.

Not only is a moving train dangerous, but that one came with very heavily armed security who had orders to shoot if they thought anybody was endangering the shipment. So we had a very specific discipline that we used in Agape Community demonstrations and not all of the communities, especially around the Seattle area, wanted to use that discipline.

Spirit: The same kind of code of conduct taught in the nonviolence trainings that guided direct action in most of the anti-nuclear movement?

Douglass: Right, and we had a number of meetings with different groups who agreed that only those trained for civil disobedience would sit on the tracks to stop the train. The rest of the people would stay back out of the way and support them, but not get in the way of the train.

We had a number of meetings where we thought we had hammered out a common discipline that everybody could agree to, and when that particular train came, it turned out that people had not agreed interiorly to the discipline. It was a very dangerous situation because people began to run at the train from all along the tracks. Now, imagine a train stretched out down the tracks and a large crowd that’s running toward the train. The people actually most at risk were the sheriff’s deputies, because they were between the train and the crowd, and on the train were the heavily armed security people.

Spirit: Were you concerned that the sheriffs or demonstrators could have been jostled into the path of the train?

Douglass: Yeah, well there were two things that could have happened. They were trying to keep the crowd away from the train as much to protect them from the guards as from the train itself. But with the crowd running forward and kind of berserk, the deputies were in danger of being pushed under the train. It was just a very chaotic kind of situation and one that we had not expected because we thought we’d made an agreement.

So we thought that was a major failure on our part. We published an issue of our Ground Zero newspaper kind of self-critiquing what had happened. Jim went to jail for that action and he actually plead guilty because he was trying to help take responsibility for what went wrong. So he served some jail time on that one as a result of the guilty plea.

Spirit: These kinds of breakdowns in nonviolence have taken place in many campaigns, even those led by Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Did Ground Zero renew its commitment to having clear agreements about nonviolence?

Douglass: Yeah, and we published that issue of the paper. It was not a popular thing to do because we mail the paper out to everybody. So we were admitting in public that we had had this fiasco and that we had not done well and that not everyone had lived up to the agreement and we had to try to do it better the next time.

We actually worked closely with the sheriff on the next one trying to keep the deputies safe, as well as everybody else, and we worked more closely with the sheriff than the base did [laughs]. So when the next train came, it was stopped and that’s the one shown in the video, “The Arms Race Within.”

[Editor: “The Arms Race Within,” a film directed by Kell Kearns and shown at the Dallas 2005 Peace Film Festival, shows Ground Zero planning for civil disobedience as the White Train came into the Bangor base in February 1985. The film shows hundreds vigiling and dozens being arrested in what the documentary described as “a triumph of nonviolence.”]

Spirit: It may have shaken things up when people didn’t adhere to nonviolence, yet it didn’t mean the end of Ground Zero’s campaign, did it?

Douglass: Oh no, and it helped us clarify how to do things and what was important. It intensified the ties we had already been building in the county because people respected the fact that we said that was a mistake, instead of trying to pretend it went well or justify it somehow.

Spirit: How did the next major action go when activists blocked the White Train in February 1985?

Douglass: The train was stopped, the people were arrested and the discipline was maintained. But when that case came to trial, people were charged with conspiracy as well as with blocking a lawfully operated train. When testimony began, they discovered that the sheriff had been part of the conspiracy so they had to drop the conspiracy part of the charges. [laughs] And then people were acquitted.

That was, I believe, the first acquittal that we had and nobody was convicted for, like, 20 years after that action. There were no convictions after that acquittal in 1985, up until about 20 years later. The process is very different now, with people allowed to put on their defenses.

One very big exception, of course, is the Plowshares action that five of our friends did at the base, which brought heavy charges and jail time. [Editor: On March 28, 2011, Stephen Kelly and Susan Crane were sentenced to 15 months in prison, Lynne Greenwald to six months, Jesuit Father Bill “Bix” Bichsel to three months, and Sister Anne Montgomery to two months after a federal jury convicted them of conspiracy, trespass and destruction of government property for cutting through fences at the Trident base.]

Spirit: So for 20 years, no one was convicted even though you kept doing civil disobedience at the Trident base in those years?

Douglass: We did, yeah, and for a long time they were not convicted. And eventually they stopped charging.

Spirit: That’s really amazing. Were charges dropped or were people found not guilty?

Douglass: There are two things. One is the sort of reasons the jurors gave, which ranged all over the map. One woman said, “Well, I call the police to arrest trespassers on my beach and they didn’t do it and why would they arrest these people on the tracks.” Other people said, “These folks (anti-nuclear protesters) shouldn’t be arrested because what they’re doing is the right thing.” It varied a lot.

Refusing to Be Complicit

Spirit: You once wrote that resistance to nuclear weapons had to be deep enough to address the societal causes of the arms race, including “our system’s exploitation of people for profit, the oppression of people based on their race, age or sex.” How is the arms race linked to economic injustice, and to racism, ageism and sexism?

Douglass: Well, the simplest way, the way we used to put it in our slideshow at the time, was that something like six percent of the world’s population controlled 40 percent of the world’s resources — way out of our share. And the whole point of the arms race is to protect what we have that really isn’t justifiably ours.

So we’re part of an empire which claims the right to not only rule the world, but to use the world. As long as we remain complicit with that, then to that extent we’re complicit with weapons like the Trident. So we were trying as much as possible to be conscious of where we were complicit and to withdraw our cooperation as much as we could.

That was why we adopted very simple lifestyles and lived communally. You know, all the sorts of things that people do when they’re trying not to live heavy on the earth, knowing that you can never be totally outside of the system. We’re all part of that system.

Spirit: After all these years of resistance to war, nuclear weapons and poverty, what does the word “nonviolence” mean to you now?

Douglass: What it means to me is our recognition that we’re all one and that any evil that we’re involved in as humanity, I’m involved in too. And also in any good, we’re all involved in that. We can make a choice in the way we live that either strengthens or weakens the good or the evil. So nonviolence is about being part of a world community by choice. The changes begin in us and then they spread.

So the kinds of civil disobedience we did at the Trident base that people are still doing are ways of using that power of taking responsibility and calling other people to join. We are trying to live simply and to resist as much as possible in our lives the economic violence that goes on all the time, and the racism that goes on.

Spirit: How would you describe the way nonviolence is related to love and to reverence for life?

Douglass: Well, I make a big difference between love and like [laughs] and I understand love as wanting what is best for the other. That is what I think we’re called to do. That doesn’t mean we have to feel warm and snuggly about everybody, but it does mean we have to make the best decisions we can for everybody’s welfare.

It’s the same kind of underlying faith that we are all one — however unlikely that may seem to us at any point — and we have to recognize that, whether or not we’re feeling it at a particular time.

Nonviolence is reverence for life. Wanting the best for the other person implies that we hold them in reverence.

We’re in the Catholic church now — however much we disagree with parts of it — and one of the most basic teachings in that church and all Christian churches is that human beings are created in the image of God. Therefore, just because we’re alive and human, we’re sacred and to be respected. We try and do that as much as we can. To me, it means not using more than our fair share of resources, sharing what we have, trying to work for peace.

Starting the Catholic Worker

Spirit: Do you recall what led you to become involved with the Catholic Worker, and to work with poor people?

Douglass: Well, I think of the quote, “When I was hungry you fed me.” [“For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in.” — Matthew 25:35]

When I was a kid, I came from a CIA family, and we lived overseas a good part of my growing-up years. At one point, we switched churches with every country, so we always went where they spoke English and they were always different denominations. [laughs] My mom and dad gave me the scriptures and said you should read this and do what it says and you’ll be OK, whatever church you go to. Being a literalist and a kid, I read it and I couldn’t figure out why we weren’t doing what Jesus said, which was to share what we had with poor people and to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, visit the prisoner and all of that.

I spent a good part of my childhood trying to figure that out with my mom. It wasn’t until I ran into the Catholic Worker, when I became a Catholic in college, that I realized there were other people who thought that Jesus meant what he said. So for me, the initial inspiration was reading these things in the scripture and being told by my parents, who worked for the CIA, that I should be doing them, and then finding later on that other people thought that and actually did do it.

Spirit: In writing about economic justice, you have written that Jesus said we cannot simultaneously love both God and money.

Douglass: You have a choice about the love of God and the love of money. You can keep what you have for yourself or you can share it with other people. I think which one you do has a lot to do with what you’re serving or who you’re serving.

Spirit: The whole U.S. economy is based on accumulating money and holding it tight, while the Catholic Worker is based on sharing with others. It’s the mirror opposite of capitalism in that way.

Douglass: In the Catholic Worker, the whole point is to share what we have with other people, but also to help people who don’t live in the Catholic Worker share what they have. At Mary’s House, I’m the only person who lives there to run it, but there’s a huge community of people from all over the country who help keep it going because they share some of their substance to pay our bills, to buy diapers, to do whatever. And in my understanding, that’s how God supports something.

If what you’re doing is in the context of God’s will, then you are supported somehow. That’s a promise from scripture too. But it isn’t like a bag of gold pieces arrives in your lap from an angel. Instead, you find a check in the mail from somebody in Seattle or somebody down the street in Birmingham. That’s how it arrives.

Spirit: In his interview, Jim Douglass said that you had wanted to start a Catholic Worker for many, many years?

Douglass: Yes. I lived in Casa Maria in Milwaukee for three or four months in 1970, and for me that was kind of an eye-opening experience. Casa Maria is one of the bigger Catholic Workers and was very active then in resistance to the Vietnam War and running a soup kitchen where we fed a couple of hundred people a day. It put out a very good paper, and offered hospitality to families in three or four houses.

So that was kind of a transformational sort of thing for me. I’d always read about the Worker up to that point, but I had never experienced it. I always thought that was something I would really feel called to do, but when you’re doing resistance and going to jail all the time, it’s not something you can do at the same time.

Spirit: Can you describe how you were influenced by Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker movement?

Douglass: Sure. The first effect was when I was a college student 18 years old and I walked into St. Paul’s University Chapel and picked up the Catholic Worker newspaper and realized for the first time that other people thought Jesus meant what he said. That was a revelation.

I was immediately a faithful reader of the Catholic Worker and did what we could as students to live that lifestyle and support it. Dorothy Day is such an incredibly good writer. I love good writing, so I don’t know how many times I’ve read The Long Loneliness. It’s right up there with Lord of the Rings. [laughs]

She just seemed to me to be writing the gospel, saying something that I knew inside was true. So that was very inspiring that people were actually doing this. Somebody was really doing this and had been doing it for years. It just helped me to figure out what to do with my life. And the more people you meet in the Catholic Worker, you find they’re all incredible.

Spirit: Incredible in what ways?

Douglass: By and large, the people I know in the Catholic Worker are just very clear about what is important and what needs to be done. They’re very committed and dedicated and great fun, almost always a good sense of humor and very creative. They’re just sort of amazing people.

At the end of The Long Loneliness, Dorothy Day writes that we’ve all experienced the long loneliness and she’s saying the cure for the long loneliness is community, and love and community come together. She talks about how the Catholic Worker all started. She writes that we were all sitting around talking and people came and people needed a place to live, and it all started while we were sitting around talking, which is basically how everything starts at the Catholic Worker.

Working for Peace — and also Justice

Spirit: The Catholic Worker is one of the few movement groups that integrates working for peace and working for justice. What was it that first led them to begin make the connection between protesting militarism and being in solidarity with people living in poverty?

Douglass: Because it’s directly out of the gospel. You know, as a kid I thought Jesus meant what he said and Dorothy Day thought the same thing. And basically, when I went to the big sophisticated theology school in Vancouver, they said exactly the same thing.

In those days, it was fashionable to try and figure out which of the scriptural things Jesus probably actually said, and one of the criteria was to find the things that nobody would want to do — and those are the things he probably really said. [laughs] So, sell all you have and give to the poor and come follow me, love your enemy, put down your sword, visit the prisoner, give your clothes to the naked, feed the hungry…

Spirit: Blessed are the peacemakers and those who hunger and thirst for justice.

Douglass: Right, exactly, and if you’re persecuted, more power to you. [laughs]

Spirit: Because the prophets before you were persecuted.

Douglass: Yeah, exactly, to say nothing of Jesus, of course. So that’s the gospel in a nutshell and the whole point of the Catholic Worker is to live the gospel. So it isn’t really a sense of trying to do something political; it’s the sense of trying to live the gospel. And, of course, that winds up being very political.

Spirit: So working against war and injustice may be radically political, yet it stems from the gospel teachings of “blessed are the peacemakers” and “feed the hungry.”

Douglass: And “love your enemy.” I mean, “blessed are the peacemakers” you can take a lot of different ways, but “love your enemy” is pretty specific.

Spirit: Catholic Workers often protest wars overseas, but also serve poor and hungry people on the streets of our own cities. Is that a message to the larger community — that we’re called to do both?

Douglass: Well, we certainly are called to do both, and I don’t see how you can talk about having a just and peaceful world if you’re only talking about overseas. I mean we live here, so we need a just and peaceful world here too.

Spirit: Speaking of a just world at home, what level of poverty do you find in Alabama? What are the needs of the people that come to your door seeking help?

Douglass: People that come to us need homes; they need jobs that pay a decent wage; they need decent public transportation; and they need education for their kids. The basic sort of economic human rights that are recognized around the world are not human rights in the United States.

Here in Alabama, we’re a poor state and we have this huge legacy of very obvious racism and it’s gone on for hundreds of years. The whole country has that legacy, but in the Deep South, you’re sitting right in the middle of it. And right now our state legislature is totally controlled by the Republican Party and is very busily trying to curtail the right to vote — just as we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Selma March.

You know, they are trying to cut back on any services to poor and vulnerable people because they don’t want to raise taxes. It’s the same thing that’s going on all over the country, but I think it’s particularly potent in the South and in Alabama.

Spirit: What methods are Republicans using to curtail voting rights?

Douglass: Well, we have voter ID requirements now. If you want to vote, you have to have an ID card, and a lot of people don’t have IDs. A lot of people in the rural South don’t drive. A lot of people are elderly or they don’t have transportation. It’s hard to go out and get a driver’s license or a state ID because you don’t have any way to get there, and all of these things cost money. If you already choose between paying your rent or buying medicine, you’re not likely to shell out another $20 or $30 for an ID card.

For people who are poor, it just adds another rung to the ladder that you have to climb to be able to have a voice. And so many of the black men in our community are in prison. They’re often in prison for nonviolent crimes, but they’re still felonies, which means they lose their right to vote.

Spirit: A massive disenfranchisement added on top of a massive level of imprisonment.

Douglass: Yeah, it’s a huge thing. This book by Michelle Alexander called The New Jim Crow makes the argument that it’s a conscious attempt or a semiconscious attempt to keep black people in their place — the same place that white people and the power structure have been trying to keep them in for hundreds of years.

___________

For more on Shelley Douglass please visit: