Book Review by Paul Von Blum

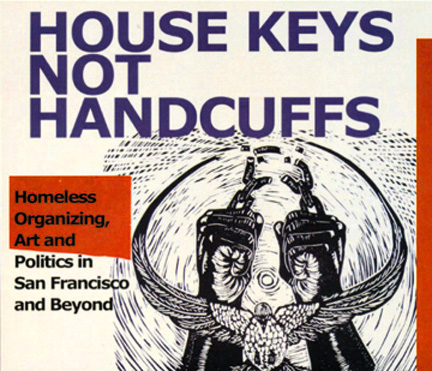

House Keys Not Handcuffs, by Paul Boden, a dramatic and disconcerting book on homeless organizing, art and policy in San Francisco and elsewhere, begins with this personal quotation that puts homelessness in the compelling human perspective it demands: “Holy shit, it is time to go home and I got nowhere to go.”

Millions of women, men and children live precarious lives on American streets and shelters, tragically beyond the concern, empathy and often even awareness of the overwhelming majority of their more privileged fellow citizens. The plight of the homeless, for political “leaders,” is mostly a mere annoyance. They are an irritant to public officials and a fruitful source of arrest statistics for police departments throughout the nation.

Far too many Americans avoid contact with homeless people, whom they regard as distasteful and inconvenient — unpleasant reminders of the huge gap in wealth and privilege in this country. Conservatives (and many others) like to tell themselves that homeless people are there by choice, simply because of their unwillingness to work hard, defer gratification and live according to society’s rules and standards.

By emphasizing house keys instead of handcuffs in the title, Boden deliberately asks his readers to understand that the homeless need homes and serious social and public health services, not arrests, prosecution, police harassment and the continuing criminalization of the poor in America. This is a central theme of this powerful volume.

It calls justifiable and powerful attention to the long record of using laws against trespassing, panhandling, loitering, vagrancy, disorderly conduct and many other variants to punish poor people and exacerbate their misery and desperation. Drug and alcohol laws are also tools in the seemingly limitless arsenal of law enforcement authorities.

Police officials likewise use injunctions and “orders to vacate” and regularly confiscate the meager possessions of the homeless, bringing additional despair to these marginalized human beings. With unaffordable fines and excessive bails, homeless people often spend time in local jails, adding criminal records to the already complex burdens of their lives. This makes it even more difficult for them to find employment and to obtain the medical and psychological services they require.

This criminalization reflects the national mania for “broken windows” policing, which ostensibly focuses on small crimes like vandalism, public drinking and loitering in order to prevent more serious crimes. This is a transparent rationalization for social policies that reinforce racism, classism and economic injustice, including the appalling numbers of homeless people in America.

Broken windows policing has led to such injustices as “stop and frisk” laws and other policies that disproportionately target people of color. At its worst, broken windows policing leads to the deaths of unarmed people. One of the most egregious examples occurred in 2014 when New York Police Department officers in Staten Island killed an African-American man with a chokehold after seeking to arrest him for allegedly selling loose cigarettes.

The book also provides a deeper understanding of the homelessness crisis in the Bay Area and, by extension, throughout the country. It provides a detailed narrative of the organizing and political activities of 30 years of homeless organizing in San Francisco. It offers an outstanding guide for contemporary activists about what has worked and what has not. It also discusses the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP), which was created to expose and eliminate the root causes of poverty and homelessness in that region.

In its decade of existence, WRAP has served as a model of community organizing that goes far beyond the single issue of not having houses for people experiencing massive poverty. Its broad-based focus on social justice addresses child abuse and domestic violence, downsizing and layoffs, racism, unlawful evictions and other illegal actions, government budget cuts, inadequate or nonexistent mental health treatment and many related issues.

WRAP has several constituent member groups, and its efforts go beyond the Bay Area. This form of coalition building is a useful guide for other activists seeking to change society at the grass-roots level, especially in a nation that has experienced the greatest degree of inequality of wealth and income in almost a century.

One striking feature of House Keys Not Handcuffs is the story of Street Sheet, told through a series of its articles from 1991 to 2014. Street Sheet is published by the Coalition on Homelessness and sold in San Francisco. It contains articles about the problems of the homeless population and is the oldest street newspaper in the United States.

Vendors distribute the newspaper on the streets of San Francisco, selling it for $1. The homeless and low-income vendors pay nothing for the papers and keep all the money they receive. These vendors are, in fact, men and women who are actually working; they might otherwise be holding cups and begging for spare change, perhaps with signs reading “Will Work for Food” or “Have a Blessed Day.”

Each month, Street Sheet reaches 32,000 readers and provides a voice for the voiceless. The paper encourages them to write about life, politics and anything else from their perspective. That vision is a conspicuous and dramatic contrast to the mainstream media in America.

The most engaging element of this book is its inclusion of 67 powerful pieces of art, making this volume a striking collection of contemporary, socially conscious art. These works are introduced in an essay by Art Hazelwood, “We Won’t Be Made Invisible: Art of Homeless Activism.”

Hazelwood is a veteran artist/activist whose works have made a major contribution to the recent history of political art, especially in California. He has been responsible for making Street Sheet a newspaper where art by and about homeless people has been published and become available to large audiences. His personal artwork has graced the pages of Street Sheet for many years. Several of Hazelwood’s pieces appear in House Keys Not Handcuffs, allowing readers a splendid sample of his work addressing homelessness, poverty and related themes.

As a curator, Hazelwood has assembled several exhibitions that reflected his exemplary commitment to using art in the long struggle for social change. “Hobos to Street People: Artists’ Responses to Homelessness From the New Deal to the Present,” which ran from 2009 to 2012, is most closely linked to the themes in the current book. That exhibition, which was shown in various California venues, featured both iconic artists from the Depression era and contemporary artists dealing with the seemingly endless struggle against poverty.

In House Keys, Not Handcuffs, Hazelwood has gathered a stunning group of contributing artists, including some major figures in contemporary political art. Readers and viewers who follow visual arts will recognize names such as Eric Drooker, Jos Sances, Doug Minkler, Christine Hanlon, Hazelwood himself and others. Notably, several unidentified visual artists also appear in this book, as well as works from the San Francisco Print Collective and other sources.

Above all, the book’s inclusion of these provocative artworks reveals once again that the arts are an integral feature of the long struggle for social justice, not a mere cultural adjunct to organizing and concerted political action. Throughout history, visual artists have mobilized their talents to support movements for social change.

In the United States, visual artists have played prominent roles in the civil rights movement, and, more recently, many have been extremely active in demonstrations supporting “Black Lives Matter” actions.

Painters, muralists, poster artists, printmakers, photographers and others have also been deeply involved in the Chicano, Asian-American, Native American and other ethnic struggles, the gay and lesbian movement, the environmental movement, various anti-war resistance activities and every other progressive movement.

Eric Drooker’s 2008 drawing for Street Sheet, reprinted in the book, is an excellent and unnerving example of the link between visual arts and the broader struggle for social justice. The artist’s image of a menacing police officer standing in front of a building representing City Hall, with a club swinging in his hand, signifies the dubious policy of governmental repression against the homeless.

The Street Sheet headline, “Police Kill Man Panhandling, No Crimes Charged,” hanging over the drawing underscores the continued violence against America’s most vulnerable population. Underneath Drooker’s work, the article about cruel and unusual budget cuts underscores official indifference, offering Street Sheet’s readers a partisan yet accurate view of official policy regarding homelessness in San Francisco.

House Keys Not Handcuffs is a persuasive reminder of the tremendous work that remains to be done to close the gap between American ideals and American realities. Paul Boden ruefully notes at the book’s conclusion that the government never stopped investing in housing; it merely stopped investing in housing for the poor. Boden and fellow homeless advocates know that there is a desperate need for federal funding for affordable housing.

Beyond that, more fundamental systemic change is required to end homelessness and provide the educational, employment, health care and other services that a decent and humane society should guarantee to everyone. This book represents a small but valuable step in generating that consciousness.