by Carol Denney

Criminalizing homelessness is the most expensive, least effective way to address homelessness. Studies prove it, reporters note it, and common sense suggests it since paying for a year of low-income housing or even a college education costs a lot less than a year in jail. So why does it sell like crazy?

From coast to coast, we’re bristling with new anti-homeless and vagrancy laws, according to “No Safe Place: The Criminalization of Homelessness in U.S. Cities,” a report by the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty.

California leads the way with an average of nine anti-homeless laws per city, according to the UC Berkeley School of Law Policy Advocacy Clinic’s new study, “California’s New Vagrancy Laws.”

These laws typically criminalize standing, sitting, lying down, sleeping, having belongings which might be used for “camping,” sleeping in your own car, sharing food with others, and asking for money. Many of these actions are unavoidable for people who have no place to go.

Why are these embarrassingly heartless laws so easy to pass and so popular? The answer is that there’s currently a political cost to any politician who insists on the creation of low-cost housing as a priority. But there is very little political cost at present to passing yet another law, even an unconstitutional law, which burdens the poor or persecutes the homeless.

Berkeley is a great case in point. Berkeley is a college town, notoriously liberal, consistently cast as comically out of touch with mainstream American politics by the national press. But mayor after mayor in Berkeley has been more than willing to override the will of the community, ignore the moral objections of religious and human rights groups, and go to bat in court for unconstitutional legislation on behalf of political groups who want the poor to just disappear.

In an interview early in his political career posted online by Berkeley author and poet John Curl, Mayor Tom Bates referred to rent control as “a no-win position” for him and “a death knell” for politicians generally. Berkeley citizens, in the absence of honest leadership on the issue of low-income and affordable housing, cite their own frustration with panhandling and homelessness as reason enough to vote repeatedly for laws of dubious constitutionality which target poor people on the street struggling with unemployment, evictions and skyrocketing rents.

U.S. District Court Judge Claudia Wilken issued a temporary restraining order in 1995 against Berkeley’s 1994 anti-panhandling law, noting that “some Berkeley citizens feel annoyed or guilty when faced with an indigent beggar.… Feelings of annoyance or guilt, however, cannot outweigh the exercise of First Amendment rights.”

Poor and homeless people are notoriously ill-equipped to hire lawyers and mount legal challenges to the anti-poor laws generated primarily by merchant associations which, in the case of the powerful Downtown Berkeley Association (DBA), get mandated “membership” payments from all the businesses within its expanding downtown footprint.

The DBA’s board is dominated by large property owners who were the primary funders of the failed anti-sitting law campaign in Berkeley’s 2012 election. There is not a single representative on the board from the poorly funded nonprofits and law clinics who work with the poor and homeless people caught up in the endless web of the criminalization of poverty.

Those are the groups who will show up in opposition to new anti-homeless initiatives. But they are much less likely than wealthy investment and property companies to be able to toss large campaign donations to councilmembers running in the next election.

The Berkeley City Council knows that circling poor and homeless people endlessly through overburdened courts and jails over unpayable fines for innocuous offenses is dumb. They tend to be intelligent people who by now have had somebody toss a copy of the report on “California’s New Vagrancy Laws” by the UC Berkeley Policy Advocacy Clinic, or the “No Safe Place” report on the criminalization of homelessness in U.S. cities from the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty (or both) on their desks. They may even have read the reports.

But it takes courage to say no to merchant associations and the University of California’s short-sighted effort to make homelessness and poverty invisible. Courage is in short supply in the Berkeley City Council chambers.

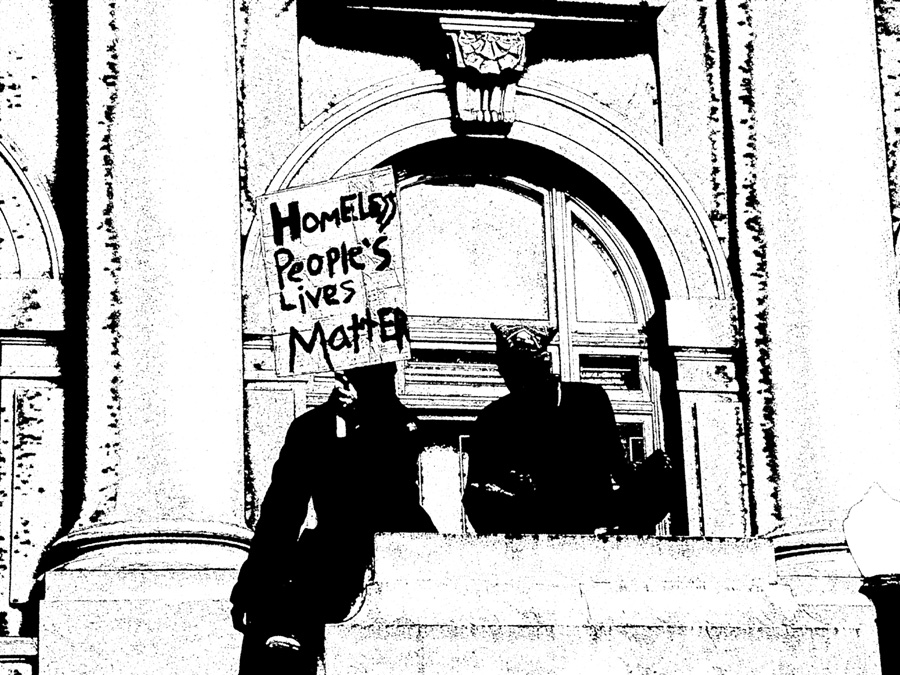

For all the opining in January and February 2015 about the Black Lives Matter campaigns, and even though the majority of those affected are people of color and people struggling with disabilities, the anti-homeless laws proposed by Berkeley City Councilmember Linda Maio at the council meeting on March 17 passed with a predictable majority, proving that Berkeley’s war on the poor will go on without interruption.

Courageous testimony at the City Council by homeless people, UC professors and students, and advocacy groups seemed to make little difference to the councilmembers who supported the proposal.

The majority of the proposal’s few citizen supporters were real estate brokers who complained about behavior which is already illegal, as Councilmember Kriss Worthington noted in his eloquent statement about the expense and ineffectuality of criminalizing more and more attributes of homelessness (such as “deploying” a blanket between 7:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m.) rather than addressing practical solutions.

“How many people have gotten clean and sober when there are consequences to their behavior?” asked Councilmember Lori Droste, proving you can put a new face on the council and raise the collective IQ not one iota.

Councilmember Jesse Arreguin removed his name as a sponsor of the anti-homeless laws, but offered the usual leavening of “services” in an ineffectual effort to “balance” the legislation, which, with all due respect to charities and humanitarian services, is a strategy consistently used in Berkeley to make it easier to pass repressive human rights violations.

Several of the councilmembers who voted for the new anti-panhandling and anti-homeless laws flatly denied that they were criminalizing homelessness. They just don’t see it. They feel obligated to respond to complaints about what was called “problematic street behavior” in 1994’s Measure N & O campaign days, and are unmoved, at least at this point, by arguments that such measures clog courts and cost money better spent on common sense solutions. They just don’t see it, and they certainly are not hearing it from their constituents.

The easy route is to give the rich, i.e., the Downtown Berkeley Association, what they want, and let the courts sort it out later at the expense of the poorly funded legal clinics and advocacy groups forced in such moments to keep track of our civil and human rights.

But the very fact of Berkeley’s history of repeatedly passing more and more restrictive laws targeting the poor proves that the laws are not doing any good in the first place, an irony noted by Berkeley Daily Planet editor Becky O’Malley, who reminded the council that repeatedly doing the same thing over and over while expecting different results is a well-known definition of insanity.