by Claire Isaacs Warhhaftig

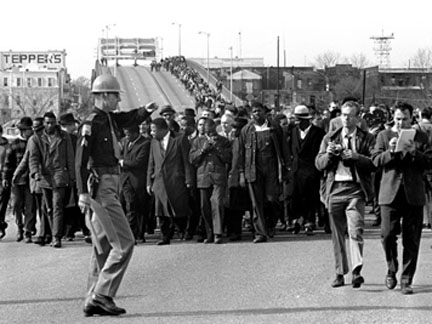

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hy was the 1965 march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, so important?

We Americans take voting for granted. Yet look at every decision we make in society, from choosing the leaders of our nation, down to the smallest, most informal social situations. Shall we order Chinese takeout or pizza? We nod our heads or perhaps just sense a consensus.

Even when conducting informal affairs, we select a temporary chair of a group or decide the time of the next meeting by simply raising our hands. This form of selection process is far from normal in many countries and cultures, but here voting and other forms of democratic decision-making is a default position, as natural as walking and talking.

At the end of the American Revolution in 1776, we needed to create a formal, legal system of democratic governance, which would also be protected by secrecy. By 1787, the U.S. Constitution had guaranteed the vote to citizens defined as white, male, and property-owning.

After the Civil War, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments — known as the Reconstruction Amendments — abolished slavery, extended the rights of due process and equal protection to all citizens, and banned discrimination in voting rights on the basis of “race, color or previous condition of servitude.”

In the early 20th century, women won the right to vote when the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in 1920. In 1971, the Twenty-Sixth Amendment lowered the voting age from 21 years to 18 years.

The federal government guarantees these rights, but the states, according to the age-old division of powers, regulate voting registration. Many former slave-holding states in the South blocked black citizens from voting by requiring literacy tests, exacting poll taxes, and using intimidation to exclude black voters. After one hundred years of struggle, the march in Selma culminated in the effort to overcome this injustice.

When the civil rights movement achieved its landmark victory with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, voting increased by the tens of thousands and some of the formerly disenfranchised African American citizens were elected to political office.

In direct response to the marches, the bloodshed and loss of life in Selma, President Lyndon Johnson, who had publicly stated his opposition to introducing any more legislation on civil rights or voting rights, presented his bill to Congress on March 15, 1965, just a week following the Selma March.

Johnson stated, “At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.

“There long-suffering men and women peacefully protested the denial of their rights as Americans. Many were brutally assaulted. One good man, a man of God, was killed.”

The Voting Rights Act also imposed “preclearance” standards by the federal government upon many Southern states to prevent them from disenfranchising African Americans with barriers such as gerrymandering and early polls closing. (“Preclearance” requires jurisdictions to receive federal approval before implementing changes to the election laws in an effort to prevent them from barring citizens from voting.)

Some states now claim that preclearance is no longer necessary. Yet, in this new century, North Carolina passed laws to eliminate early voting, same-day registration and out-of-precinct voting. These methods have been particularly useful to African American voters who often opted to complete all steps in one day.

The Supreme Court has tended to look favorably on such changes. But watchful people are concerned that alterations such as these weaken the original intent of the Voting Rights Act and could lead to further infringements on the freedom to vote.

By committing ourselves to vigilance in safeguarding our voting rights, the spirit of Selma will inspire us, and ensure that the March for freedom goes on.